* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Pitfalls in the Estimation of the Severity of a

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

History of invasive and interventional cardiology wikipedia , lookup

Cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Marfan syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Turner syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Echocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Artificial heart valve wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Mitral insufficiency wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

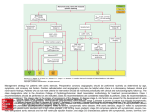

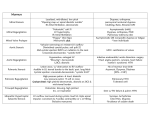

JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE ISSN: 2330-4596 (Print) / 2330-460X (Online) VOL.2 NO.4 JULY 2014 http://www.researchpub.org/journal/jcvd/jcvd.html Pitfalls in the Estimation of the Severity of a “Low-Flow Low-Gradient” Aortic Valve Stenosis in absence of Contractile Reserve Wilhelm P. Mistiaen, MD, ScD, PhD, Philip Van Cauwelaert, MD and Philip Muylaert, MD Abstract— In some patients, the severity of aortic valve stenosis is difficult to estimate. In an elderly patient with aortic valve stenosis, heart failure and other co-morbid conditions, severity of aortic valve stenosis was estimated with a dobutamine stress echocardiography. The patient died six days after valve replacement. A literature search revealed pitfalls in the diagnostic procedure and difficulties in the interpretation of dobutamine stress echocardiography. Absence of contractile reserve, low mean transvalvular gradient and presence of coronary artery disease in this patient can be considered as increased risk. However, valve replacement might be offered on an individual basis. Keywords — Aortic valve stenosis, low-flow low-gradient, dobutamine stress echocardiography. Cite this article as: Mistiaen WP, Van Cauwelaert P, Muylaert P. Pitfalls in the Estimation of the Severity of a “Low-Flow Low-Gradient” Aortic Valve Stenosis in absence of Contractile Reserve. JCvD 2014;2(4):213-217. I. INTRODUCTION T HE only life-prolonging treatment for symptomatic severe calcified aortic valve stenosis (CAVS) is aortic valve replacement (AVR). The criteria for severe CAVS are an aortic valve area (AVA) of less than 1.0 cm², a mean transvalvular gradient (TVG) of over 40 mmHg and an aortic peak jet velocity (PJV) of over 4 m/sec. However, there are some difficulties that can be encountered in the evaluation of some patients.1 First, symptoms are notoriously difficult to provoke in elderly patients.2,3 Second, there can be a discrepancy between indicators of severe CAVS.3,4 This makes use of these This paper is submitted for review on January 15, 2014. There has been no funding or financial support to declare. There are no conflicts of interests. Affiliations: University of Antwerp, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Antwerp, Belgium; Artesis-Plantijn University College, Dept. of Healthcare Sciences, Antwerp, Belgium (first author); ZNA Hospital Middelheim, Dept. of Cardiovascular Surgery, Antwerp, Belgium (second and third author). Correspondence to ([email protected] ) 213 measurements as sole parameters undesirable.1 Third, concomitant disorders such as arterial hypertension and coronary atheromatosis, which are frequent in patients with CAVS 5,6 can have an additional effect on the left ventricular (LV) function.1 We present a case of an elderly man with CAVS in whom difficulties and pitfalls have been encountered, which could have been avoidable. II. CASE A male patient of 86 years had a long history of cardiovascular disease. This included hypertension (AHT), diabetes with retinopathy, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease complicated with acute myocardial infarction and with episodes of unstable angina, atrial fibrillation and bradycardia, which needed pacemaker implantation as well as recurrent transient ischemic attacks. Episodes of heart failure were treated with infusions of dobutrex. The patient also had polycythemia vera, which was under control. The patient complained of gradually increasing dyspnea. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 115/90 mmHg. There were no clinical signs of overt heart failure. An ejection murmur was clearly audible. Electrocardiography showed a pacemaker rhythm. Echocardiography showed a poorly contractile dilated hypertrophic LV, with an ejection fraction (EF) of 13% and an increased LV end-diastolic pressure. The aortic valve was calcified with a mean TVG of 13 mm Hg. AVA was estimated at 0.96 cm².There was a moderate mitral valve regurgitation. A dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) confirmed the presence of a dilated LV with poor function. Infusion of 40 µg Dobutamine did not result in an increase in AVA. There was no mentioning of change in LV contractility. The patient was diagnosed with severe CAVS with deteriorating LV function. He was referred for AVR. Coronary angiography also revealed serious disease of the dominant right coronary artery. The left coronary artery was moderately affected. The EUROScore was 14%. The patient underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (A venous jump graft on the right coronary artery) and AVR (Medtronic Mosaic size 27). A slow weaning of extracorporeal circulation was possible. The postoperative course was initially favourable. Arterial partial oxygen pressure was kept over 95 mmHg, by mechanical ventilation for 54 hours with 40% oxygen and positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 mmHg. The JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE ISSN: 2330-4596 (Print) / 2330-460X (Online) VOL.2 NO.4 JULY 2014 http://www.researchpub.org/journal/jcvd/jcvd.html patient was sedated for 2 days. On the second day, recurrent short bursts of ventricular tachycardia were observed, for which intravenous amiodarone was started. There was a prolonged need for inotropic medication: decreasing doses of noradrenalin for 2 days, dopamine for 3 days, with cardiac index varying between 1.2 and 2.5 litres/minute/m². Left atrial pressure reached levels of 33 mmHg. After 5 days, the patient could be transferred to the ward. At the 6th day, an electromechanical dissociation occurred. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation had no result. Necropsy showed a severely dilated left ventricle, severe pulmonary oedema but no signs of recent ischemia or bleeding. There were no other abnormalities observed at gross examination. TABLE I SOURCES OF ERROR IN ESTIMATING SEVERITY OF CAVS Ref Source Significance 4 Vena contracta Overestimation of severity 1,3,4,9 Pressure recovery Overestimation of severity 7,12 Mal-alignment of Doppler beam Underestimation of PJV Aortic valve regurgitation Underestimation of AVA 7,9,11, 12,20 Underestimation of left ventricular outflow tract cross section Underestimation of flow, stroke volume and of AVA 4,14 Beat to beat variation of Doppler wave Mismatch between AVA and TVG III. DISCUSSION Echocardiography is the first choice to diagnose and estimate the severity of CAVS.7,8 It can describe the parameters of other valves, of LV function and of other cavities.9 Echocardiography is operator dependent, however. The classical parameters which can be measured or calculated by echocardiography are mean TVG, AVA, and PJV. The left ventricle can be examined for its function and presence of hypertrophy. Mean TVG is more flow dependent than AVA, while the latter is more prone to measurement errors. AVA needs also indexing. PJV is more robust and reproducible. PJV can be a part of an integrated approach, together with AVA and mean TVG.1,7,10,11 Using these common parameters, a spectrum in presentation of symptomatic CAVS can be discerned, ranging from a normal-flow high-gradient CAVS with preserved LVEF,12 paradoxical low-flow low-gradient case with preserved LVEF and a low-flow low gradient case with low LVEF. Low-flow states with small AVA and discrepantly low TVG need to be distinguished from a pseudo-severe CAVS 1,12, because a low TVG does not exclude severe CAVS. A more comprehensive approach is required for difficult cases.11,12 Before considering measurement inconsistencies, other sources of error must be ruled out. These can be found in table I. These sources can be responsible for errors in calculation of AVA and stroke volume and hence for a mismatch between AVA and TVG. Moreover catheter based and echocardiographic measurement of AVA and TVG are not necessarily interchangeable.1,3,4,9 Furthermore, mutual inconsistent criteria for severity of CAVS must be taken into account: an AVA of 1.0 cm² corresponds better with a mean TVG of 30-35 mmHg and less with 40 mmHg, which is considered a cut-off value. It might be tempting to lower this cut-off to 0.8 cm², but is has been demonstrated that an AVA of less than 1.0 cm² predicts excessive mortality irrespective of the level of TGV and of symptomatic status .3,10,13 Several additional hemodynamic and other parameters can be measured to assess the severity of CAVS in difficult cases. These can be found in table II. The current case is a low-flow state with low LVEF, in which an echocardiography at rest might not solve the problem. Application of DSE has a class IIa recommendation with an evidence of level B.3,4,9,13 If a contractile reserve is present, the infusion of dobutamine during 214 CAVS = Calcified aortic valve stenosis; PJV = peak jet velocity; AVA= aortic valve area; TVG= transvalvular gradient DSE increases the transvalvular flow and stroke volume index (SVI) because of the inotropic effect.14 For the latter, SVI is a better parameter than cardiac index, since mean TVG depends more on flow per beat than on flow per minute.13 Induction of ischemia and ventricular arrhythmias must be avoided, by using low doses and longer stages to reach a steady state. Three possibilities can be discerned.2,4,7,8,12 1) Increase of stroke volume index (>20%) and in TVG (>40 mmHg) or PJV (>4 m/sec) with fixed AVA (<1.0 cm²). This is a true severe CAVS. 2) Increase of stroke volume index and in AVA (>0.2 cm²), but without increase in TVG or PJV: this is a pseudo-severe CAVS. 3) No increase in stroke volume index due to lack in contractile reserve: the severity of CAVS cannot be determined by this technique.13 The presence of coronary artery disease, of previous infarction or of other myocardial diseases (exhaustion by prolonged afterload mismatch can nullify the inotropic effect of dobutamin. This could be the case in the current patient. The rise in flow and TVG will be less than expected .13 An additional parameter of DSE is the projected AVA. The variable increase in flow during DSE can make interpretations for individual patients difficult. To overcome this difficulty, the projected AVA (the expected AVA with standard flow of 250ml/sec) can be derived from the AVA/flow curve. A projected AVA<1.0cm² is considered as marker for severe CAVS.2,4,13-15 The use of DSE has its limitations: its results predicts only the operative risk, not the long-term results.13,16 Preoperative risk factors for operative mortality are absence of contractile reserve, mean TVG under 20 mmHg and presence of multi-vessel coronary artery disease.13 Operative mortality in patients without contractile reserve is estimated between 30% JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE ISSN: 2330-4596 (Print) / 2330-460X (Online) VOL.2 NO.4 JULY 2014 http://www.researchpub.org/journal/jcvd/jcvd.html TABLE II ADDITIONAL PARAMETERS FOR ADEQUATE ESTIMATION OF SEVERITY OF CAVS Ref Parameter Significance 1 Energy loss coefficient More equivalent to AVA; requires inclusion of several parameters; prone to error 1 Stroke work loss Takes pressure recovery into account; is more predictive for outcome than AVA 1,11,12 Stroke volume index Requires inclusion of several parameters; it is superior to cardiac index but prone to error 1 Valvulo-arterial impedance Measures the total ventricular afterload; the effect of pseudonormalized hypertension can be underestimated 21 Upstroke of Doppler wave form Is an indication of ejection time and severity of CAVS; is slower in severe CAVS 8,10 Pulmonary artery pressure Is an indication for left ventricular diastolic dysfunction 12,13 Abnormal longitudinal left ventricular function Predictor of adverse outcome after AVR; indicates left ventricular fibrosis 12,14 Calcium score on computer tomography Estimates severity of CAVS and is an indicator of its rate progression survivors of AVR, benefit from the operation, since it relieves the LV from the after-load mismatch. Moreover, operative risks of AVR improved over time.19 The available literature reveals a large number of possible parameters in the evaluation of the severity of CAVS in difficult cases. The most commonly used parameters are shown in table II. No single parameter can represent the severity of CAVS in all patients. For patients with a low-flow state, the parameters which are most easy to determine and with high sensitivity and specificity, as shown in table I, should be selected. The experience of the operator plays a major role herein. IV. CONCLUSIONS. In this difficult case, even DSE could not solve all problems in estimating the severity of CAVS. Even an explicitly documented lack of contractile reserve could be partially reversible due to concomitant treatment of coronary artery disease. What could be helpful in the decision making are documenting the projected AVA, the presence of myocardial fibrosis, the plasma level of B-type natriuretic peptide and the calcium score. This patient was operated in an era when trans-catheter aortic valve implantation was upcoming. In such patients, this approach could be an alternative. V. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CAVS = Calcified aortic valve stenosis; AVA= aortic valve area; AVR= aortic valve replacement; 16-18 and 50%. In patients with low TVG, operative mortality increased to 53% and in patients with prior AMI, this was even 67%.14,16 These data illustrate the necessity of individual tailoring of the treatment of this condition by AVR, for which a class IIa, level C evidence has been proposed by the European Society of Cardiology / European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.13 However, a long-term beneficial effect of the operation in terms of New York Heart Association functional status and improvement of LVEF has been observed. The lack of contractile reserve is not necessarily due to an irreversible LV dysfunction and is not always a reason to deny the operation.16 These observations seem to justify the operation in this case, but some comments have to be made. Age is in itself not a reason to deny AVR 5, but it should be taken into consideration together with the co-morbid conditions. On the one hand, there were some conditions increasing the operative risk: a “pseudo-normalized” hypertension, atrial fibrillation and the need for a pacemaker. The very low mean TVG, the need for coronary artery bypass grafting, a previous AMI and the very low LVEF in this patient were all predictors for an increase in operative mortality. A very low LVEF and an absence of increase in TVG during DSE could indicate to an absence of contractile reserve. This was not described explicitly in this patient. On the other hand, if this absence of contractile reserve was due to ischemia during DSE, this absence could be reversed by coronary artery bypass grafting. Furthermore, 215 There are no conflicts of interest to declare. There was no financial support References [1] Pibarot P, Dusmenil JG. Improving Assessment of Aortic Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:169-180. [2] Picano E, Pibarot P, Lancellotti P, Monin JL, Bonow RO. The Emerging Role of Exercise Testing and Stress Echocardiography in Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2251-2260. [3] Chrysohoou C, Tsiachris D, Stefanadis C. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: Challenges in diagnosis and therapy. Maturitas 2011;70:349-353 [4] Abbas AE, Franay LM, Goldstein J, Lester S. Aortic Valve Stenosis: To the Gradient and Beyond—The Mismatch Between Area and Gradient Severity. J Intervent Cardiol 2013;26:183-194. [5] Mistiaen W, Van Cauwelaert Ph, Muylaert Ph, Wuyts Fl, Harrisson F, Bortier H.Risk factors and survival after aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004; 13(4): 538-544. [6] Mistiaen W, Van Cauwelaert P, Muylaert P, De Worm E. 1000 pericardial valves in aortic position: risk factors for postoperative acute renal function impairment in elderly. J Cardiovasc Surg 2009;50(2):233-237. [7] Baumgartner H. Low-Flow, Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Still a Challenging Condition. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60(14):1268-70. [8] Lindman BR, Bonow RO, Otto CM. Current Management of Calcific Aortic Stenosis. Circ Res. 2013;113:223-237. [9] Eleid MF, Mankad S, Sorajja P. Assessment and management of aortic valve disease in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Heart Fail Rev 2013;18:1-14. [10] Lancellotti P, Magne J, Donal E, Davin L, O’Connor K, Rosca M, Szymanski C, Cosyns B, Piérard LA. Clinical Outcome in Asymptomatic JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE ISSN: 2330-4596 (Print) / 2330-460X (Online) [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] VOL.2 NO.4 JULY 2014 http://www.researchpub.org/journal/jcvd/jcvd.html Severe Aortic Stenosis. Insights From the New Proposed Aortic Stenosis Grading Classification. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:235-43. Pibarot P, Dusmenil JG. Editorial Assessment of aortic stenosis severity: when the gradient does not fit with the valve area. Heart 2010;96(18): 1431-1433. Pibarot P, Dusmenil JG. Editorial comment. Paradoxical Low-Flow, Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis Adding New Pieces to the Puzzle. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:413-415. Pibarot P, Dusmenil JG. Low-Flow, Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis With Normal and Depressed Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1845-1853. Awtry E, Davidoff R. Low-Flow/Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis. Circulation 2011;124:e739-e741. Clavel MA, Burwash IG, Mundigler G, Dumesnil JG, Baumgartner H, Bergler-Klein J, Sénéchal M, Mathieu P, Couture C, Beanlands R, Pibarot P. Validation of Conventional and Simplified Methods to Calculate Projected Valve Area at Normal Flow Rate in Patients With Low Flow, Low Gradient Aortic Stenosis: The Multicenter TOPAS (True or Pseudo Severe Aortic Stenosis) Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:380-6. Tribouilloy C, Lévy F, Rusinaru D, Guéret P, Petit-Eisenmann H, Baleynaud S, Jobic Y, Adams C, Lelong B, Pasquet A, Chauvel C, Metz D, QuéréJP, Monin JL. Outcome After Aortic Valve Replacement for Low-Flow/Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis Without Contractile Reserve on Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1865-1873. Monin JL, Monchi M, Gest V, Duval-Moulin AM, Dubois-Rande JL, Gueret P. Aortic Stenosis With Severe Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Low Transvalvular Pressure Gradients. Risk Stratification by Low-Dose Dobutamine Echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:2101-2107. Monin JL, Lancellotti P, Monchi M, Lim P, Weiss E, Piérard L, Guéret P. Risk Score for Predicting Outcome in Patients With Asymptomatic Aortic Stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:69-75. Levy F, Laurent M, Monin JL, Maillet JM, Pasquet A, Le Tourneau, T Petit-Eisenmann H, Gori M, Jobic Y, Bauer F, Chauvel C, Leguerrier A, Tribouilloy CC. Aortic Valve Replacement for Low-Flow/Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis. Operative Risk Stratification and Long-Term Outcome: A European Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1466-1472. Minners J, Allgeier M, Gohlke-Baerwolf C, Kienzle RP, Neumann FJ, Jander N. Inconsistent grading of aortic valve stenosis by current guidelines: haemodynamic studies in patients with apparently normal left ventricular function. Heart 2010;96:1463e1468. Higgins JR, Arimie R, Currier J. Low Gradient Aortic Stenosis: Assessment, Treatment, and Outcome. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2008; 72:731-738. . 216 JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE ISSN: 2330-4596 (Print) / 2330-460X (Online) VOL.2 NO.4 JULY 2014 http://www.researchpub.org/journal/jcvd/jcvd.html Wilhelm P. Mistiaen graduated as MD in 1984 and earned a PhD in 1999 and in 2009. He is currently employed as associate professor at the University of Antwerp and Artesis-Plantijn University College, Antwerp, Belgium. He is a member of the Society of Heart Valve Disease and published about 20 papers concerning aortic valve disease and replacement. The current interest are complications after aortic valve replacement and their predictors 217