* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Body Fluid Exposures

Viral phylodynamics wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Forensic epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Canine parvovirus wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS wikipedia , lookup

Diseases of poverty wikipedia , lookup

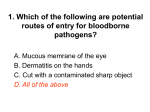

Blood Body Fluid Exposures (BBFE) Information For Patients Background Transmission of blood-borne infections may occur through parenteral (e.g. needle stick injury), mucous membrane exposure (e.g. splashes to eyes, mouth), and non intact skin exposure (blood or other body fluid splash to cuts, eczema, wound, etc). The greatest risk of contracting a bloodborne virus is via a skin penetration injury (‘needlestick’) sustained with a sharp hollow-bore needle that was recently removed from a bloodcontaminated source. The risk of transmission is increased if there was visible blood on the needle prior to injury and if the needle injury was deep to the recipient and if the needle was large i.e. the bigger the volume of fresh blood inoculation the bigger the potential risk of sufficient numbers of any virus that may have been present in the source’s blood being able to establish an infection in the injured person. Although many infections may be transmitted by such contact, the most concerning are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In addition, localised skin and soft tissue bacterial infection can occur at the site of the inoculation injury by introduction of e.g. staphylococcal bacterial species from our own skin. If a localised bacterial skin infection does occur this can be treated with antibiotics. Overview When intact, the skin serves as an effective physical barrier to the entry of infectious microbes into the body. However, a special situation exists in terms of mucous membranes. The presence of a moist mucous layer tends to prolong the viability or life of relatively fragile viruses, such as HIV and HCV, which cannot survive so long in drier environments. However, HBV has been demonstrated to survive on dry surfaces for days to months and potentially remain capable of causing infection, while HCV has been shown to be able to survive on environmental surfaces for a minimum of 16 hours but not for 4 days. Mucous membranes have a higher blood vessel concentration coupled with a relatively permeable cellular layer which gives rise to a transmission risk of any body fluid splashes of HBV, HCV, and HIV across this membrane and potentially into the bloodstream. However, in practice, at least for occupational HIV exposures (as opposed to sexual contact), transmission rarely occurs via this route. Intact skin does not possess these characteristics and is virtually impermeable unless its integrity is disrupted e.g. eczema, dermatitis, cuts. After initial exposure, animal models have shown that HIV can multiply within dendritic (nerve) cells of the skin and mucosa within the first 48 hours before spreading through lymphatic vessels and becoming a systemic infection. This time lapse from initial introduction of the virus to systemic spread allows an opportunity to inhibit the replication of the virus using post exposure HIV prophylaxis if the source of the blood or body fluid was known or high risk for HIV infection. Blood and body fluids - especially if visible blood is present, should be considered potentially infectious. Unless blood is present, saliva, sputum, sweat, tears, faeces, nasal secretions, urine, and vomitus carry a much lower risk of transmission of HBV, HCV, and HIV but are nevertheless potentially infectious. Frequency/Risk of Infection after BBFE Incident Only a relatively small percentage of people in the general population carry a bloodborne virus. 1. HIV The risk for developing HIV after a needlestick injury involving an HIV-infected person is around 0.3% i.e. 3 per 1000 chance of developing HIV after injury if the source was HIV positive. Stated another way, even if the source was HIV positive there is a 99.7% chance the injured person will not develop HIV. Factors that increase the odds of HIV transmission and infection after skin penetration exposure are depth of injury, visibility of blood on device, exposure from a needle that was in an artery or vein, and terminal illness in the source person/patient (because there will be more virus present at that time). Note that the risk of HIV transmission from exposure of HIV-infected fluids on the mucosa of health care workers is extremely low (0.09% or 9 per 10,000) and that no cases of HIV infection after exposure of intact skin to HIV-contaminated fluids have been reported. If the source is known or high risk for HIV, prophylaxis can be considered by an infectious disease physician as soon as possible after the injury - within the first 2-4 hours (but up to 72 hours) post exposure. There are some at least theoretical risks with this prophylaxis treatment approach but it may reduce the risk of developing HIV by half. 2. HCV Following a needle stick, if the source was positive for HCV, the risk of contracting HCV averages about 1.8%, range 0-10%, (i.e. average less than 2 per 100 chance). There is no prophylaxis treatment that can be given in this situation even if the source is known HCV positive. 3 HBV After a needle stick injury, if the source is known and if source is hepatitis B positive the risk of developing HBV infection ranges from 6-30% if the injured person has not been vaccinated for HBV . If the injured person has ever been fully vaccinated to HBV and does not have renal disease or is not immuncompromised, then immunity from developing HBV is almost certain. If the injured person is not vaccinated or uncertain about this then your GP may advise beginning a hepatitis B vaccination course within a few days and/or offer immunoglobulin prophylaxis depending on the circumstances. When Is Blood Test Follow Up Required? Depending on the circumstances your GP may advise you to have one or more blood tests up to six months from the BBFE exposure incident. It can take up to six months to know for certain whether an infection has occurred or not. This can be a potentially stressful time and wait, you may wish to consider counselling. Keep it in context though, only a small percentage of the population has HIV, HBV or HCV infection. Even if the source had hepatitis B virus, the most common of these viruses in the population, the risks are still comparatively small of developing a HBV infection. If you were not already vaccinated against HBV then by starting a new vaccination course to HBV or having immunoglobulin soon after the injury, then the chances of catching HBV can almost be eliminated. Further Reading Sources http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/bbp/ http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/bbp/guidelines.html