* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download View

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Heart arrhythmia wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

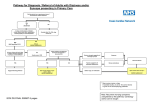

GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SYNCOPE IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT (ED) Simon Clarke Emergency Department Frimley Park NHS Foundation Trust Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 1 1. INTRODUCTION Syncope is defined as a transient loss of consciousness with loss of postural tone, due to global cerebral ischaemia, usually associated with spontaneous, rapid and complete recovery. It is a relatively common symptom and has been estimated as being the primary complaint in 1.7% of presentations to UK Emergency Departments (ED) [1]. There are >1600 presentations to Frimley for syncope. Syncope is a symptom not a disorder in itself; it may be caused by a large number of diseases (see Box 1) which range from benign to potentially life-threatening conditions. Syncope may present diagnostic difficulties and it has been estimated that initial ED history, examination and ECG will only suggest a diagnosis in 22-60% of cases [1-4]. This diagnostic uncertainty is reflected in the variation in rates of specific diagnoses and the wide range of published admission rates for syncope (25-83%) [1, 2, 3, 5-13] (see Appendix 2). Even after extensive investigations no cause will be found in up to 3-24% of cases [5, 14-16]. Concern about missing the serious underlying causes of syncope has been shown to lead to low-risk patients being admitted for cardiac monitoring and further tests which have both resource and clinical risk implications. 1 year mortality ranges from 5.6%-15%, but there is little published data on short-term mortality rates: Silverstein [2] noted a 3% in-hospital rate while Quinn [17] reported a 1 month death rate of 1.4%. A literature search was undertaken to find if there is any evidence for identifying patients who can be safely discharged from the ED. In particular, the following evidence was scrutinised: 1. studies that have identified individual factors (from the history, examination, or investigations that are available in the ED) that suggest a specific cause. 2. studies that have developed risk stratification scores for patients with syncope, with special reference to those that were undertaken in EDs 3. published guidelines by accredited professional bodies Medline and Embase were searched using the terms: [syncope OR collapse]. References were reviewed Appendix 2 contains a summary of the individual studies scrutinised. Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 2 Box 1. Causes of Syncope [22, 27, 29, 30, 31] NEURALLY (REFLEX)-MEDIATED Vasovagal – emotional distress, orthostatic stress Carotid sinus syncope Situational – cough, sneeze, micturition, swallowing, defecation, visceral pain, laughing, post-prandial, post-exercise Atypical ORTHOSTATIC Autonomic failure - age-related, diabetic neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, amyloid neuropathy, multiple system atrophy, spinal cord injuries, uraemia Drug-induced – hypotensives, negative inotropes, CNS depressants, anticholinergics Volume depletion – dehydration, blood loss, Addison’s CARDIOVASCULAR Arrhythmias – sinus node dysfunction, AV conduction disease, PPM malfunction, SVT, VT, drug-induced arrhythmias (esp QT prolongers) Structural heart disease – outflow obstruction (valvular stenosis, HOCM), atrial myxoma, pericardial disease/ effusion Myocardial ischaemia Pulmonary vascular – PE, pulmonary hypertension Aortic dissection NEUROLOGICAL Subclavian steal syndrome PSYCHIATRIC Chronic anxiety Major depression Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 3 2. CLINICAL FEATURES WITH PROGNOSTIC VALUE Syncope itself does not predict future morbidity and mortality [18] but there are a number of studies that have shown that cardiac syncope does have prognostic value [2, 3, 7, 15, 1921]. One cohort study indicated that patients with syncope of unknown cause also had a slightly increased risk of all cause mortality compared with matched patients without syncope [21]; but the authors referenced some recent electrophysiological studies have revealed that 45-80% of cases of unknown syncope have a cardiac origin. Orthostatic syncope has also been shown to be associated with a two-fold increased risk of mortality, primarily due to associated co-morbidities [22]. A number of risk scores have been developed (Table 1) which used multivariate analysis to identify clusters of features that predict different outcomes. Table 1. Risk Stratification Scores Score Martin, 1997 [23] Oh, 1999 [20] Sarasin, 2003 [24] OESIL Score, 2003 [25] San Francisco Syncope Risk Score, 2004 [8] EGSYS Score [16] Risk Factors abnormal ECG age >45 years history of ventricular arrhythmias history of congestive cardiac failure 1. abnormal ECG 2. absence of nausea or vomiting in the prodrome 3. underlying cardiac disease abnormal ECG age >65 years history of congestive cardiac failure abnormal ECG age >65 years history of cardiac disease absence of prodrome abnormal ECG dyspnoea history of congestive cardiac failure haematocrit <30% Palpitations before syncope Heart disease or abnormal ECG or both Syncope during effort Syncope while supine Precipitating or predisposing factors or both (warm, crowded place/ prolonged orthostasis/ fear, pain, emotion) Nausea/ vomiting in prodrome Outcome CVS deaths & arrhythmias at 1 year. 1 & 2 predictive of arrhythmias at 1 year. 3. predict mortality at 1 year. Arrhythmias (unspecified follow up) in patients whose initial ED assessment could not identify any cause. All cause mortality at 1 year. Serious outcome (death, MI, arrhythmia, PE, CVA, significant haemorrhage, return to ED for related condition) within 1 week. 2 year mortality Unfortunately, there are potential limitations in each system. Martin’s, Sarasin’s, the OESIL and EGSYS risk scores used long-term outcomes which are not relevant when considering Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 4 whether a patient should be admitted from an ED; conversely, the San Francisco Syncope Risk Score was developed to predict serious outcomes within 1 week of the index visit. Also, none of the systems has been successfully validated: no attempt has been made with Martin’s, Sarasin’s or the EGSYS systems. Reed [13] showed that the OESIL score was safe if a score of 0 was taken as the cut-off but this was at the expense of a 55% in admissions, while Ammirati [4] applied the score to his population of patients yet found that 24.6% of those who were eventually diagnosed with cardiac syncope were discharged from the ED. The validity of the San Francisco system has also been questioned with sensitivities as low as 68% [11, 12] being reported. However, the similarity between the systems is striking and all of them identified cardiac disease, particularly congestive heart failure, as predicting adverse outcomes. Table 2 shows the ECG criteria defined by each system. Table 2. ECG Criteria used by Risk Scores Martin, 1997 Oh, 1999 Sarasin, 2003 OESIL, 2003 San Francisco, 2004 EGSYS, 2008 Conduction disorders – CHB, Mobitz II block, pacemaker malfunction Rhythm abnormalities – VT (≥3 beats), sinus pauses ≥2s, symptomatic SVT, slow AF (RR intervals >3s) Symptomatic sinus bradycardia Old MI LVH/RVH Other Conduction disorders – LAD, BBB, IV conduction delay, any AV block, short PR interval Rhythm abnormalities – AF, atrial flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, junctional rhythm, paced rhythm Repetitive/frequent premature ventricular beats Old MI LVH/RVH Conduction disorders – BBB, Mobitz I, bifascicular block, sinus pause ≥2s - <3s Rhythm abnormalities – AF, sinus bradycardia 36-45/min. Multiple premature ventricular beats Old MI LVH/RVH Conduction disorders – CHB, 2nd degree AV block, BBB or IV conduction delay Rhythm abnormalities – AF, atrial flutter, SVT, multifocal atrial tachycardia, frequent or repetitive premature supraventricular or ventricular complexes, VT (sustained or non-sustained), paced rhythm Old MI LVH/RVH LAD ST/T wave changes consistent with ischaemia Not sinus rhythm New change compared with old ECG Conduction disorders – 2nd or 3rd degree AV block, BBB Rhythm abnormalities – SVT, VT, pre-excited ventricular beats Sinus bradycardia Acute or old MI LVH/RVH, Long QT, Brugada Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 5 3. CLINICAL FEATURES THAT SUGGEST A DIAGNOSIS Since cardiac and orthostatic syncope are associated with an increased risk of mortality, it would be informative to identify the features that can be used to diagnose these types of syncope. In particular, the search concentrated on the following key aspects of the history: precipitants, prodrome, and recovery. 3.1. Neurally-Mediated Syncope Precipitants: Typical precipitant eg fear/anxiety, hot/crowded place, pain, instrumentation [6, 14, 27, 33] Prolonged standing [27]. During/after meal [27]. After exertion (in the absence of structural heart disease with a fixed cardiac output eg AS) [27] Head movement, wearing a tight collar, shaving suggests carotid sinus sensitivity [14, 33]. Prodrome: Vasovagal syncope tends to have a longer prodrome than cardiac syncope but there is considerable overlap [6, 33]. Abdominal discomfort during the prodrome [28] Recovery: Nausea/sweating during the recovery [28] Other Features: Absence of cardiac disease [27]. Long history (up to 4 years) of recurrent episodes [28] 3.2. Orthostatic Syncope Precipitants: After standing up (especially after exertion) [27]. Prolonged standing especially in hot, crowded place [27] Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 6 Soon after changes to medication particularly drugs with hypotensive effects [27, 33] or those that interact with them. Other Features: History of autonomic neuropathy (eg DM, Parkinson’s disease) [27, 29, 30, 31, 33] 3.3. Cardiac Syncope Precipitants: While sitting or lying [6, 14, 28, 33] During exertion [28] After exertion, when other features of a structural heart disease with a fixed cardiac output (eg aortic stenosis) are identified [14, 33]. Fast palpitations occurring prior to syncope [14, 28] Prodrome: Absent or brief (<5 sec) prodrome [6, 33] although there is considerable overlap with vasovagal syncope. Nausea and vomiting during the prodrome are very unusual features of arrhythmic syncope [20]. Recovery: Immediate recovery with an absence of fatigue [32] Other Features: Symptoms/risk factors suggesting acute coronary syndrome, PE etc [33]. A past history of cardiovascular disease [33] Drug history: eg QT prolongers, diuretics [33] A positive family history of sudden cardiac death, Brugada syndrome, HOCM, long QT syndrome [27, 33]. Examination features of structural heart disease with outflow obstruction, or cardiac failure [33]. ECG abnormalities [33]. 3.4. Features Distinguishing Seizures from Syncope Although brief seizure activity may occur during syncope, tongue-biting, cyanosis, and frothing at the mouth are suggestive of a convulsion rather than syncope [34]. Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 7 Recovery of orientation <30 seconds suggests syncope [33] whereas disorientation during the recovery phase suggests a seizure [34]. Box 2. American College of Physicians, 1997 [29, 30]. Criteria for Admission ADMISSION INDICATED: History of: o IHD, CCF, ventricular arrhythmia o Accompanying chest pain Physical signs of: o Significant valvular disease, CCF, CVA, focal neurology ECG findings: o Ischaemia, arrhythmia (serious bradycardia of tachycardia), increased QT, BBB ADMISSION OFTEN INDICATED: Sudden loss of consciousness with injury, rapid heart action, or exertional syncope Frequent spells, suspicion of IHD or arrhythmia (eg use of drugs associated with torsades de pointes) Moderate-severe orthostatic hypotension Age> 70 years 4. PUBLISHED GUIDELINES 4.1. The American College of Physicians These guidelines were published in 1997 [29, 30]; they included recommended criteria for admission (see Box 2) but some of these indications were rather vague (eg no definition was given for ‘significant’ valvular disease or ‘moderate-severe’ orthostatic hypotension). Crane [1] undertook a retrospective cohort study of the ACP guidelines (see Appendix 2). This showed that there was a significant difference in 1 year mortality between those in whom admission was indicated, often indicated and not indicated. However, there was no significant difference in 1 week and 1 month mortality which are arguably more relevant outcomes when deciding who needs emergency admission. Indeed, following the guideline would have lead to one patient being discharged who died within 1 week and admission Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 8 rates would have been increased (only 68% of those who fulfilled the criteria for admission were actually admitted). Box 3. American College of Emergency Physicians, 2004 [9]. Criteria for Admission. Patients for Whom an Underlying Cause of Syncope is not Immediately Apparent from the Initial assessment Level A Evidence. None. Level B Evidence. 1. Evidence of heart failure or structural heart disease. 2. In the presence of factors that suggest a high risk (from the San Francisco Risk Factor score): Abnormal ECG (acute ischaemia, dysrrhythmias, significant conduction abnormalities) Haematocrit <30% History or examination findings of heart failure, ischaemic or structural heart disease Level C Evidence. None It would seem that the ACP guidelines have limited application for Emergency Department use. 4.2. American College of Emergency Physicians The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) developed guidelines in 2001 [33] which they updated in 2007 [26]. The 2001 version studied the evidence for stratifying risk in patients presenting with syncope and, in particular, looked at features of the initial ED assessment that predicted cardiac syncope. ACEP devised criteria for admission and categorised them according to the level of evidence that underpinned them; these included level B and C evidence based criteria. A subsequent retrospective cohort study [9] indicated that using only the level B criteria had 100% sensitivity and 81% specificity for identifying cardiac syncope (ie all patients who were finally diagnosed with cardiac syncope were identified as high risk in the ED). However, using both level B and C criteria would have increased the admission rate by 13.5% without increasing sensitivity. Therefore, the 2007 revision of the guidelines removed the level C criteria (see Box 3). Unfortunately, the guideline incorporates the San Francisco Syncope Risk Score which has subsequently had its external validity questioned [11, 12] (see section 2), so again, it may not be suitable for use in our population of patients. 4.3. European Society of Cardiology Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 9 The ESC guidelines were first developed in 2004 [27] but were significantly rewritten in 2009 [22]. In particular, syncope was defined more precisely, with transient loss of consciousness not caused by global cerebral ischaemia (eg CVA, seizures & migraine) being separated from the list of causes. The aspects of the guidelines that are most relevant to ED practice recommend an initial assessment which involves a history, examination (including lying and standing BP measurements) and a 12-lead ECG. The information from this clinical evaluation is used to Box 4. European Society of Cardiologists, 2009 [22]. Criteria for Admission 1. Severe structural or ischaemic heart disease Heart failure LV ejection failure Previous MI 2. Clinical/ECG findings suggesting arrhythmic syncope Syncope during exertion or supine Palpitations at time of syncope FH of sudden cardiac death Non-sustained VT Bifascicular block or other IV conduction delay (QRS ≥120ms) Sinus bradycardia <50/min. or sinoatrial block in absence of –ve inotropes or physical training Pre-excited QRS Long or short QT Brugada Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy answerthree key questions: co-morbidities 1. Is3.itImportant syncope? Severe anaemia Electrolyte abnormalities 2. If it is syncope, can the underlying aetiology be diagnosed? 3. If the aetiology cannot be determined, is there any evidence to suggest an increased risk of cardiovascular events or death? Box 4 shows the clinical factors that have been deemed to indicate a high risk and they were derived from international guidelines for cardiac pacing and risk stratification/ prevention of Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 10 sudden cardiac death. These are outcomes that are relevant when trying to decide whether patients need to be admitted from the ED. 5. DISCUSSION The clinical approach published by the European Society of Cardiologists (22) contains the most up to date evidence, including the EGSYS score. It would seem sensible to adopt the overall strategy developed by the ESC and their criteria for admission: 1. Patients who are diagnosed with a condition that requires admission (eg MI, PE etc). 2. Those in whom a diagnosis is not immediately apparent but who have the risk factors listed in Box 4. The criteria used for admission are derived from other guidelines that do not directly address syncope and do not contain all of the ECG criteria identified by the risk scores (Table 2). The factors noted in all of the other risk scores (Table 1) but not listed by the ESC warrant further investigation but have little evidence to suggest a short-term risk. Therefore, they could be categorised as criteria when discharge can be considered with early out-patient review in a cardiology clinic. Additionally, it should not be forgotten that there may be other reasons for admission such as elderly patients who live alone and have no social support, who would be at risk if they collapsed at home and were unable to summons help. Patients who do not fit any of these criteria can be considered safe for discharge for follow up in primary care, possibly with referral for tilt-table testing in the elderly. The suggested guideline is in Appendix 1 (below). Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 11 6. REFERENCES 1. Crane SD. Risk stratification of patients with syncope in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2002; 19; 23-27. 2. Silverstein MD, Singer DE, Mulley AG, et al. Patients with syncope admitted to medical intensive care units. JAMA. 1982; 248; 1185-1189. 3. Kapoor WN. Evaluation and outcomes of patients with syncope. Medicine. 1990; 69; 160-174. 4. Ammirati F, Colivicchi F and Santini M. Diagnosing syncope in clinical practice. 2000; 21; 935-940. 5. Blanc JJ, L’Her C, Touiza A, et al. Prospective evaluation and outcome of patients admitted for syncope over a 1 year period. Eur Heart J. 2002; 23; 815-820. 6. Martin GJ, Adams SL, Martin HG, et al. Prospective evaluation of syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 1984; 13; 499-504. 7. Eagle KA, Black HR, Cook EF, et al. Evaluation of prognostic classifications for patients with syncope. Am J Med. 1985; 79; 455-460. Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 12 8. Quinn JV, Stiell IG, McDermott DA, et al. Derivation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with short-term serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 43; 224-232. 9. Elseber AA, Decker WW, Smars PA et al. Impact of the application of the American College of Emergency Physicians recommendations for the admission of patients with syncope on a retrospectively studied population presenting to the emergency department. Am Heart J. 2005; 826-831. 10. Quinn J, McDermott D, Stiell I, et al. Prospective validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; 47; 448-454. 11. Sun BC, Mangione CM, Merchant G et al. External validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49; 420-427. 12. Birnbaum A, Esses D, Bijur P, et al. Failure to validate the San Francisco Syncope Rule in an independent emergency department population. Ann Emerg Med. 2008; 52; 151-159. 13. Reed MJ, Newby DE, Coull AJ, et al. The Risk stratification Of Syncope in the Emergency department (ROSE) pilot study: a comparison of existing syncope guidelines. Emerg Med J. 2007; 24; 270-275. 14. Wayne HH. Syncope. Physiological considerations and an analysis of the clinical characteristics in 510 patients. Am J Med. 1961; 30; 418-438. 15. Day SC, Cook EF, Funkenstein H, et al. Evaluation and outcome of emergency room patients with transient loss of consciousness. Am J Med. 1982; 73; 15-23. 16. Del Rosso A, Ungar A, Maggi R, et al. Clinical predictors of cardiac syncope at initial evaluation in patients referred urgently to a general hospital: the EGSYS score. Heart, 2008; 94; 1620-1626. Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 13 17. Quinn J, McDermott D, Kramer N, et al. Death after emergency department visits for syncope: how common and can it be predicted. Ann Emerg Med. 2008; 51; 585-590. 18. Kapoor WN and Hanusa BH. Is syncope a risk factor for poor outcomes? Comparison of patients with and without syncope. Am J Med. 1996; 100; 646-655. 19. Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, et al. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. New Engl J Med. 1983; 309; 197-204. 20. Oh JH, Hanusa BH and Kapoor WN. Do symptoms predict cardiac arrhythmias and mortality in patients with syncope? Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159; 375-380. 21. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. New Engl J Med. 2002; 347; 878-885. 22. The task force for the diagnosis and management of syncope of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009; 30; 2631-2671. 23. Martin TP, Hanusa BH and Kapoor WN. Risk stratification of patients with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 29; 459-466. 24. Sarasin FP, Hanusa BH, Perneger T, et al. A risk score to predict arrhythmias in patients with unexplained syncope. Acad Emerg Med. 2003; 10; 1312-1317. 25. Colivicchi F, Ammirati, Melina D, et al. Development and prospective validation of a risk stratification system for patients with syncope in the emergency department: the OESIL risk score. Eur Heart J, 2003; 24; 811-819. 26. Huff JS, Decker WW, Quinn JV, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49; 431-444. Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 14 27. Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt DG, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope – update 2004. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25; 2054-2072. 28. Alboni P, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37; 1921-1928. 29. Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes M, et al. Diagnosing syncope part 1: value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126; 989-996. 30. Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes M, et al. Diagnosing syncope part 2: unexplained syncope. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 127; 76-86. 31. Kapoor WN. Evaluation and management of the patient with syncope. JAMA. 1992; 268; 2553-2560. 32. Calkins H, Shyr Y, Frumin H, et al. The value of the clinical history in the differentiation of syncope due to ventricular tachycardia, atrioventricular block, and neurocardiogenic syncope. Am J Med. 1995; 98; 365-373. 33. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of patients presenting with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37; 771-776. 34. Hoefnagels WAJ, Padberg GW, Overweg J, et al. Transient loss of consciousness: the value of the history for distinguishing seizure from syncope. J Neurol. 1991; 238; 3943. 35. Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Maher Y et al. Syncope of unknown origin. The need for a more cost-effective approach to its diagnostic evaluation. JAMA. 1982; 247; 26872691. Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 15 7. APPENDICES 7.1. APPENDIX 2. EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT SYNCOPE GUIDELINE Syncope is defined as a transient loss of consciousness with loss of postural tone, due to global cerebral ischaemia, usually associated with spontaneous, rapid and complete recovery. See Box 1 for the list of causes. Initial assessment includes: full history examination (including measurement of lying/standing BP – see Box 2) 12-lead ECG Seizure? See Box 3 Trauma Head injury manage accordingly No LOC? IS IT SYNCOPE? All of the following: 1. Was LOC complete? 2. Was LOC transient with rapid onset & short duration? 3. Was postural tone lost? 4. Was recovery spontaneous, complete & without sequelae? NO Fall Fall’s pathway o Altered mental status manage accordingly Persistent LOC? o Coma? manage accordingly o 4 Intoxication? manage accordingly CARDIAC? See Box ADMIT YES CAN THE AETIOLOGY BE DETERMINED? o YES Emergency Department Syncope Guideline ORTHOSTATIC? See Box 5 ASSESS MOBILITY ON CLINICAL DECISION UNIT CONSIDER DISCHARGE IF SAFE SOCIAL CIRCUMSTANCES Page 16 NO NEURALLY-MEDIATED? See Box 6 IS THERE EVIDENCE SUGGESTING A HIGH RISK OF CVS EVENTS OR DEATH? YES HIGH RISK. See Box 7 DISCHARGE ADMIT NO MODERATE RISK. See Box 8 CONSIDER DISCHARGE IF SAFE SOCIAL CIRCUMSTANCES WITH EARLY OUTPATIENT REVEIW LOW RISK. DISCHARGE BOX 1. CAUSES OF SYNCOPE No high or moderate risk factors NEURALLY (REFLEX)-MEDIATED Vasovagal – emotional distress, orthostatic stress Carotid sinus syncope Situational – cough, sneeze, micturition, swallowing, defecation, visceral pain, laughing, postprandial, post-exercise Atypical ORTHOSTATIC Autonomic failure - age-related, diabetic neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, amyloid neuropathy, multiple system atrophy, spinal cord injuries, uraemia Drug-induced – hypotensives, negative inotropes, CNS depressants, anticholinergics Volume depletion – dehydration, blood loss, Addison’s CARDIOVASCULAR Arrhythmias – sinus node dysfunction, AV conduction disease, PPM malfunction, SVT, VT, drug-induced arrhythmias (esp QT prolongers) Structural heart disease – outflow obstruction (valvular stenosis, HOCM), atrial myxoma, pericardial disease/ effusion Myocardial ischaemia Pulmonary vascular – PE, pulmonary hypertension Aortic dissection BOX 2. ORTHOSTATIC HYPOTENSION NEUROLOGICAL 1. Measure BP after patient has been supine for 5 minutes Subclavian steal syndrome 2. Stand patient for 3 minutes – take BP measurements intermittently & record the lowest PSYCHIATRIC reading Chronic anxiety Orthostatic hypotension: Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Major depression Fall in SBP ≥20mmHg Fall in DBP ≥10mmHg Page 17 BOX 3. FEATURES THAT DISTINGUISH SEIZURES FROM SYNCOPE Although brief seizure activity may occur during syncope, tongue-biting, cyanosis, and frothing at the mouth are suggestive of a convulsion rather than syncope. Recovery of orientation <30 seconds suggests syncope whereas disorientation during the recovery phase suggests a seizure. BOX 4. FEATURES SUGGESTING CARDIAC SYNCOPE Precipitants: While sitting or lying. During exertion. After exertion, with other features of a structural heart disease with a fixed cardiac output (eg aortic stenosis). Fast palpitations occurring prior to syncope. Prodrome: Absent or brief (<5 sec) although considerable overlap with vasovagal syncope. Nausea and vomiting during the prodrome are very unusual features of arrhythmic syncope. Other Features: Symptoms/risk factors suggesting acute coronary syndrome, PE etc. A past history of cardiovascular disease. Drug history: eg QT prolongers, diuretic. A positive family history of sudden cardiac death, Brugada syndrome, HOCM, long QT syndrome. Examination features of structural heart disease with outflow obstruction, or cardiac. ECG abnormalities: Sinus bradycardia < 40/min. in awake, repetitive sinoatrial block, sinus pauses >3 secs. Mobitz II 2nd degree AV block or complete heart block Alternating LBBB & RBBB VT or rapid SVT Non-sustained polymorphic VT, long or short QT PPM/ICD malfunction with cardiac pauses Acute ischaemia +/- MI Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 18 BOX 5. FEATURES SUGGESTING ORTHOSTATIC SYNCOPE Precipitants: After standing up (especially after exertion). Prolonged standing especially in hot, crowded place. Soon after changes to medication especially drugs with hypotensive effects or those that interact with them. Other Features: History of autonomic neuropathy (eg DM, Parkinson’s disease). BOX 6. FEATURES SUGGESTING NEURALLY-MEDIATED SYNCOPE Precipitants: Typical precipitant eg fear/anxiety, hot/crowded place, pain, instrumentation Prolonged standing. During/after meal. After exertion (in the absence of structural heart disease with a fixed cardiac output eg AS). Head movement, wearing a tight collar, shaving suggests carotid sinus sensitivity. Prodrome: Vasovagal syncope tends to have a longer prodrome than cardiac syncope but there is considerable overlap. Abdominal discomfort during the prodrome Recovery: Nausea/sweating during the recovery. Other Features: Absence of cardiac disease. Long history (up to 4 years) of recurrent episodes. BOX 7. REQUIRES ADMISSION - HIGH RISK OF SHORT-TERM ADVERSE OUTCOMES 1. Severe structural or ischaemic heart disease Heart failure LV ejection failure Previous MI 2. Clinical/ECG findings suggesting arrhythmic syncope Syncope during exertion or supine Palpitations at time of syncope FH of sudden cardiac death Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 19 BOX 8. MODERATE RISK – ECG CRITERIA FROM PUBLISHED RISK SCORES RBBB Mobitz I 2nd degree AV block 1st degree AV block AF or atrial flutter Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 20 Emergency Department Syncope Guideline Page 21