* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

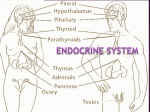

Download clinical endocrinology - Nakladatelství KAROLINUM

Vasopressin wikipedia , lookup

Hypothyroidism wikipedia , lookup

Hormone replacement therapy (male-to-female) wikipedia , lookup

Neuroendocrine tumor wikipedia , lookup

Hyperthyroidism wikipedia , lookup

Growth hormone therapy wikipedia , lookup

Hypothalamus wikipedia , lookup