* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Labelling of injectable medicines administered in anaesthesia

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

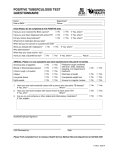

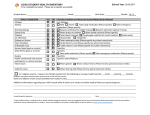

1 Labelling of injectable medicines administered in anaesthesia. Recommendations of the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Therapy (SEDAR)1 , the Spanish Safety Reporting System in Anaesthesiology and Critical Care (SENSAR)2 and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP-España)3 . JI Gómez-Arnau1,2 , MJ Otero3 , A Bartolomé2 , C Errando1, D Arnal1,2 , AM Moreno3, G Puebla1,2, JM Marzal1,2 , JA Santa Úrsula1,2, R González2 , M Pérez2 , S García del Valle1,2 , A González2 , A Domínguez-Gil3 . Correspondence: [email protected] Conflict of interests This work has been partially financed by Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (PI 07/0654). SENSAR has received financing from Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad, CCAA de Madrid and Drager Hispania, S.A. None of the authors attached to SENSAR have received personal financing. ISMP- España has got financing from Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad and from CCAA de Castilla y León. 2 INTRODUCTION Errors involving medication represent an important health problem causing relevant welfare and economic impact 1-3. Besides, they provoke distrust in the patients and lack of confidence in the professionals and the sanitary institutions. The development and introduction of effective practice is being promoted with the aim to reduce drug errors and to improve safety of the patients. These recommendations, prepared by Sistema Español de Notificación en Seguridad en Anestesia y Reanimación (SENSAR) and by Sociedad Española de Anestesiología, Reanimación y Terapéutica del Dolor (SEDAR) in collaboration with Instituto para el Uso Seguro de los Medicamentos (ISMP-España) are aimed to prevent medical treatment mistakes caused by the lack of identification of the preparations and their route of administration, which could be avoided with the adoption of basic measures. They include the adoption of a code of standard colors for the labelling of syringes used in anaesthesia that has been recommended by the European Union and is in use in other countries. Together with the principal recommendations there are basic indications for the labelling of other injectable drug preparations administered in this field, and advice for the differentiation of administration routes at special risk. SCOPE 1.- The aim of these recommendations is to standardize labelling and facilitate the identification of syringes and containers (bags, bottles, etc) containing injectable medicaments to be used during the anaesthetic procedure and to identify the route of administration, in order to reduce the risk of medication errors. 2. These recommendations are very specific about the size, shape and color of the labels, the minimum information they should contain and their placement. 3. The application of these recommendations does not preclude the health professional from verification of the name of the drug, dose and expiration date shown in the labeling of the original container. 3 4. The use of a code of colors (which allows the identification of a medicament within certain therapeutic group) to label the syringes is an aid to identification of drug groups, but it must not replace the obligation of reading the label; so, before the drug is to be administered, the anesthesiologist or the health professional must always verify properly the medicament and its concentration. 5. These recommendations are applicable in operating rooms, anaesthetic procedures outside the operating rooms and other places where the anaesthesia and sedation are provided. 6. These recommendations do not apply to manufactured medicaments. AIMS 1. To promote the use of safe practice for the identification of the drugs administered to the patients and their routes of administration. 2. To standardize the labelling of syringes and containers with injectable medicaments and their routes of administration. 3. To reduce the mistakes in the administration of injectable drugs and to improve safety of the patients. BACKGROUND The preparation and administration of injectable medicaments is a complex process subject to many possibilities of error. Several studies show high rates of errors related to the preparation and administration of injectable drugs in different hospital settings (anesthesia, critical care, emergency department, hospitalization units, etc). It is remarkable that one of the reasons of these mistakes is the lack of standardization of the procedures 4-7. The reports about safe practices in drug therapy recommend the adoption of basic measures to improve the procedures and prevent these mistakes. Such recommendations are applicable to every medical environment. 4 The lack of labeling of injectable medicaments is one of the main causes of mistakes when injectable drugs are used. Therefore, one of the basic practices should be that all the containers and devices with medicaments should be labeled with full and legible labels to identify clearly which medicament contains such device; this label must remain until the medicament is administered8-12. Another well know mistake is the wrong route administration. It is very common that a patient has more than one access for different parenteral routes allowing interconnection; this can provoke some confusion between the administration routes13-15. To prevent these mistakes there are certain measures mainly based in using a device with a specific connection which does not permit the medicament to be administered through the wrong route (provided it has been commercialized), to verify in that precise moment that the route is the correct and to identify the different administration routes, especially those of high risk (epidural, intrathecal, intraarterial)13-15. During the anaesthetic procedure there is a high possibility of making mistakes in the administration of medicaments, as several drugs use to be simultaneously administered. It is known that there is one mistake of every 133 anaesthetic procedures16. The proportion of mistakes that affect to the patients is great than in other areas and it is due to the characteristics of the drugs used in this field17. It is estimated that one in 20 mistakes is serious and one in 250 is mortal18. The most frequent medication errors in anaesthesia include the confusion of syringes and blisters, mistakes with the administration devices, and those with the route of administration, especially between the intravenous and epidural routes18-19. In Spain anaesthesia-related medication errors are a big part of all the mistakes recorded20. There are many recommendations to prevent the mistakes of drug administration in anesthesia. These include the usefulness of reading the labelling of the medicament; to label the syringes and the bottles containing medicaments with a standard and correct label; double checking each medicament before its administration; to place suitably the drugs in the anaesthesia trays or cars; to stock properly the drugs in drawers and cupboards21-24. Recent recommendations in the USA propose, as well, the standardization of drug 5 concentrations, speed of administration, etc; adoption of new technologies for administration; use of medicaments prepared by pharmacy services and the introduction of a culture of safety25. The recent Declaration of Helsinki about safety in anaesthesia recommends, explicitly, that all medical institutions must develop protocols and provide specific labels for syringes used during anaesthesia26-26bis. The guidelines of safety and quality in anaesthesia of the European Union, support that these labels must follow an international code of standard colors27. The recommendations compiled in this work show the adoption of this code of colours, solutions for the labelling of other preparations of injectable drugs administered during the anaesthetic procedures and the routes of administration. These recommendations could follow beyond the operating room, due to the necessity of treatment to be continued (i.e. epidural analgesia); so, in a concrete hospital setting it is important that all health care workers know the recommendations. Considering the possible turnover of health care professionals and that of patients (inside the hospital), or among health services and institutions, SENSAR, SEDAR and ISMP-España consider that it is necessary to establish national standards to normalize the labelling of syringes and containers with drugs and the administration routes; this would avoid the difference in procedures between departments, institutions and even regional variations. Labelling of syringes containing injectable drugs There are several recommendations for the user-applied labelling of syringes containing the injectable medicaments used during the anaesthesia. The professional societies of many countries have adopted the same code of colours to identify the therapeutic groups of those medicaments usually used in anaesthesia with the aim to have an international standard system for that purpose28-38. It should be noted that Great Britain and Ireland are using different codes depending on the hospitals until 2003, when decided to adopt the standard codes used in USA, Australia and New Zealand in spite of the problems involved35-39-40. 6 The list below shows some of the recommendations and international standards for the labeling of syringes that contain medicaments, according to the current regulations for anesthesia and critical care: USA. Published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists in 2004 and reviewed in 200928, the guidelines are based on standards published by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and the International Organizations for Standardization (ISO) 29-30. Canada. Has developed the standards of Canadian Standards Association of 1998, reviewed in 2010 by the Canadian Anaesthesiologist’s Society 31-32. Australia and New Zealand. Compiled in the Guidelines for the Safe Administration of Injectable Drugs in Anaesthesia, published by the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, according to the standards AS/NZS 4375 from Joint Technical Committee HT/7 published in 199633-34. Great Britain and Ireland. The Anaesthetist Association of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) and the Royal College of Anaesthetist (RCA) published jointly, in 2003 the report Syringe Labeling in Critical Care Areas, which was reviewed in 200435-36. France. The Société Française d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation (SFAR) published in 2006 Prévention des erreurs médicamentenses en anesthésie. Recommandations de la SFAR37. Italy. The Societá Italiana di Anestesia Analgesia Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva (SIAARTI) published in 2007 Syringe labeling in Anesthesia and Intensive Care38. The identification of the medicaments used in anaesthesia through a standard code of colors is a strategy adopted by many of the countries. SENSAR, SEDAR and ISMP-España consider a good deal to promote the establishment of this safety practice in order to reduce drug errors in anaesthesia; they also support the adoption of this standard code for the labelling of syringes. 7 It is important to outline that the use of drugs in anaesthesia has its own characteristics because during an anaesthetic procedure it is usually required only one drug from each therapeutic group and the anaesthesiologist prescribe, prepare, label and administer the medication itself they are going to use41. Outside the operating rooms, it is possible to use several medicaments from the same group, so it is not convenient to label the syringes following this code of color42-44. Labelling containers of injectable medicines There are not specific standards in anaesthesia about labeling of bags, bottles, syringes for infusion pumps or other containers or devices which contain drugs. Nevertheless, the characteristics of this labelling must not be different from those used in other fields, except that the concentration must be clearly write and readable. SENSAR and SEDAR, in collaboration with ISMP- España want to promote a practice of safety: to label correctly all the bottles containing injectable medicaments according to the recommendations of the different institutions 8-12, 45. Likewise, this standard includes the minimum information that must appear in the labels for the medicaments used. The prevention of mistakes due to confusion of the epidural and intrathecal routes is specially remarkable in the field of anaesthesia and pain therapy. Therefore, our proposal is to use the yellow color for the labels of containers of medicaments assigned to epidural and intrathecal routes, according to the recommendations of the National Patient Safety Agency46 which other countries are already using12. Each institution must consider the system already established for the labelling of bags, bottles or other containers with injectable medicaments, which are prepared in different facilities, in order to have standard criteria for the whole institution. Since the patients can be moved from the operation room to other wards with drug perfusions and infusion devices, the steps to be taken must follow a protocol and must reach a consensus with other health 8 professionals and units within the institution (nursery, critical care facilities, cardiology, emergency, hospital pharmacy, etc). Labelling of administration lines Several organizations have recommended to put labels to identify the administration lines at special risk (i.e. epidural, intrathecal, intraarterial) in patients who receive medicaments through different routes13-15. There is not a code of colors established worldwide. Exception are the epidural and intrathecal routes being yellow the color12,46 and the intraarterial route being red the color chosen 12,47. Even more, some organizations do not support the use of a code of colors (except again for the epidural and the intrathecal) because its efficacy has not been evaluated in the prevention of mistakes and there is not a standard approved worldwide13,15. SENSAR and SEDAR, in collaboration with ISMP-España recommend to label the infusion lines and the use of the mentioned colors according to the system in Australia and New Zealand 12. On the other hand, the three organizations support the development and introduction of specific devices for each route with different systems of connection, as they seem effective barriers to avoid mistakes. Nowadays there are specific systems for the administration of medicaments through enteral feeding lines48 and in a short time there will be specific connection devices for the neuraxial route46. As in the case of the labeling of bags or bottles containing injectable drugs, it is advisable that the measures adopted in each institution (while there are not other of widespread use) to identify the administration routes, have to follow a protocol and reach a consensus with the rest of health professional and units (nursery, critical care, cardiology, emergency, hospital pharmacy, etc). RECOMMENDATIONS 9 1. General Recommendations 1.1. Labelling of syringes, bottles and routes. 1.1.1. The syringes, bottles and bags containing medicaments must have labels clearly identifying the drug contained. If the content of a syringe, bag, etc is not correctly labeled, it must never be administered. 1.1.2. The protocols for labelling of syringes and other bottles containing drugs do not preclude the mandatory identification of the medicament in its original container; besides, it is essential to read carefully the instructions in order to make the correct preparation and administration provided by the manufacturer. 1.1.3. The preparation, labelling and administration of the drug must be carried out, if possible, by the same person. 1.1.4. Once the syringes and bags are prepared with the medicaments, they must be immediately labeled. Preparing and labelling a syringe with a drug can not be started until the previous one is not finished. Do not prepare drugs for several patients simultaneously. 1.1.5. Time between preparation and administration must be as short as possible. 1.1.6. Once the medicaments are prepared, must be placed in a standard position on the trays, in the operating rooms or any other places in which the anaesthetic procedures could be performed, and they must follow a predefined and standard order all around the institution. Drugs assigned to different administration routes will be allocated in different places. 1.1.7. One injectable drug should not be used for different patients. The injectable drug that is not used in that patient, should be thrown away. 1.1.8. The medication administered must be quoted in the anaesthesia record, in the medication sheet or in any other section of the patient medical record. 1.1.9. It is necessary to label the ends of the tubes or lines used to administer the medicaments through the epidural, intrathecal and intraarterial routes. 1.1.10. If possible, it is better not to use interchangeable systems of administration or infusion, with non-matching connections for the different administration routes. 10 1.2. Complementary Recommendations To label clearly and completely the injectable drugs used in anaesthesia is a good practice to prevent the mistakes of medication, but it is not the only one existing. The aim of this report is not to exhaustively report all safety practices. Here, due to their relevance, we remind some complementary measures. 1.2.1. The stockage of medicaments must be organized and standardized in all the operating rooms, drawers and cupboards, carts, trays or other devices used to identify them correctly and to avoid confusion. 1.2.2. There must be a limit for the amount of drugs and its presentations. If possible, it should be avoided to stock and to use more than one concentration49 especially of drugs at risk, such as morphine, phenylephrine and heparin. 1.2.3. Drugs used for regional anaesthesia procedures as well as the neuromuscular blocking agents must be stocked in a specific and differentiated area49.The vials and blisters containing concentrated solutions of potassium chloride should not be stocked into the operating room. 1.2.4. It is recommended to do a protocol, and to standardize concentration and dilutions of the high-risk injectable infusion drugs. The concentrations should be the same that those in the emergency/resuscitation/critical care areas. 1.2.5. If possible, the administration of medicaments will be verified by a second person who should check both the drug and the concentration. It is advisable to automatize the procedure through an electronic verification system (i.e. bar code). The medicaments intended for the epidural or intrathecal routes should have to be checked by a second person. 2. Labelling of syringes 2.1. Size and characteristics Each label measures should be 35 to 45mm long and 15 to 25 mm wide. They must stick properly, with a special adhesive characteristics, to avoid to come off the syringe. 11 The paper they are made must allow to write with ballpoint or other pens with permanent ink. 2.2. Color It must be adjusted to the colors showed in Table 1. These colors are those of the Pantone scale. Antagonistic drugs will be differentiated with diagonal bars of 1 mm long of the same color of the agonists. These bars will have a slope of 45º and will alternate with 1 mm white bars. The name of the medicament is writting in the middle of the label without any bar around. The color of the text will be black to produce bigger contrast, except for the adrenaline and succinylcholine, whose names will be written over a black stripe in the same color that was used for the background. The text will be written in Arial typography with a minimum size of 10 to facilitate reading. 2.3. Information contained in the label The label will show at least: the generic name of the drug and its concentration expressed in ml (i.e. 5mg/mL). The concentration must not be expressed as a proportion (i.e. 1:1000; 1:10.000)12,50, 51.. In the case of drugs with similar names, it is advisable to remark in capital letters the different letters52-54 (TALLman lettering) in order to reduce the possibility of confusion. Measurement units accepted worldwide should be used and the use of abbreviations prone to error should be avoided55. Specially, it is advisable to avoid the use of the Greek letter mu “µ”,” for “µg”, and it is preferred to use “mcg” or “microgram”. Use "mL" instead of “cc”. If there is an automated system with bar code or similar, the label should include such a code. 2.4. Label placement Labels must be stuck horizontal (long axes of the label and syringe aligned) allowing the reading of the syringe graduation lines. 12 Table 1. International color code system for the labeling of syringes containing medicaments. Therapeutic Group Benzodiazepines Antagonists of benzodiazepines Hypnotics Non depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents Antagonists of not depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents Depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents Examples* Diazepam, midazolam Flumazenil Tiopental, propofol, ketamine Vecuronium, rocuronium, atracurium, cisatracurium Neostigmine, sugammadex† Succinylcholine Opioids Opioids antagonists Morphine, fentanyl Naloxone Local anesthetics Antiemetics‽ Lidocaine, bupivacaine Droperidol, ondansetron, dexametasone Atropine Haloperidol, clorpromazine Ephedrine Anticholinergic agents Neuroleptics‽ Vasopressors, except adrenaline Adrenaline‡ Hypotensive agents Adrenaline PantoneR Colour Ħ Orange 151 Orange 151 with diagonal white bars Yellow Red 811 Red 811 with diagonal white bars Upper part: name in red 811 over black bottom. Rest: red 811 Blue 297 Blue 297 with diagonal white bars Grey 401 Salmon 156 Green 367 Salmon 156 Violet 256 Upper part: name in violet 256 over black bottom. Rest: violet 256 Violet 256 with diagonal white bars White Nitroglycerine, urapidil, hidrazaline Miscellaneous Oxitocine, antibiotics, heparine * The examples included are representative of the medicaments of each group; they are not restrictive. Ħ Pantone is a registered scale colour (see http://www.pantoneespana.com/pages/pantone/color_xref.aspx) † The supplier of sugammadex provides labels for its allocation in the anesthetic record and in the patient treatment sheet. ‽ Neuroleptics are used in the perioperative period as antiemetics. Droperidol has been included specifically as antiemetic according to the authorized indications. Dexametasone has been included as antiemetic although it is also used for other purposes. ‡It is advisable to have prefilled syringes. 13 3. Labelling of containers of injectable medicines. All bags, bottles, pump syringes or other containers or devices which contain medicaments prepared to be administered, must be identified with user-applied labels. 3.1. Size and Characteristics The size of the labels should be 70 to 110 mm long and 50 to 70 mm wide for bags and bottles, and 45 to 65 mm long and 25 to 35 mm wide for pump syringes. They must be firmly stick to avoid release. The paper of the label must allow to write with a ballpoint or other pens with permanent ink. 3.2 Color Labels must be white, except those assigned to medicaments to be administered by the epidural or intrathecal routes, which should be yellow. The text must be black, Arial letter typography or similar, minimum size 10 or 12 points. 3.3. Information contained in the label The label must offer, at least, the following information: - Generic name of the medicament - As in 2.4. in the case of similar names, it is advisable to remark in capital letters those different letters (i.e. DOBUTamine-DOPamine)52-54. - Total amount of the added medicament (i.e. 500mg) and total volume of fluid in the bottle, expressed in mililiter (i.e. 100 mL) - Concentration of the medicament expressed in unit/mililiter (i.e. 5 mg/mL). The concentration must not be expressed as a ratio (i.e. 1:1000; 1:10.000)12, 50, 51 - Complete name of the patient - Number of medical record or date of birth (depending on the second ID used in each institution) In addition, if necessary, it is important to write the following information: - Administration route. It will be always included in those assigned to medicaments to be administered through epidural and intratechal routes with a size of letter of, at least, 12 points, bold typography. 14 - Infusion speed. - Infusion time. - Date and hour of preparation. - Stability or expiring date if it is less than 24 hours. Measurement units accepted worldwide should be used, and the use of abbreviations prone to error avoided55. Specially, it is advisable to avoid the use of the Greek letter mu “µ”, for “µg”, the use of “mcg” or “microgram”should be preferred. Use "mL" instead of “cc”. The name of the medicament, its amount, the concentration and the patient’s name should be written in bold, with a size of letter bigger than the rest of the information. In the case there is an automated system with bar code or similar, the label should include such a code. 3.4. Label placement Label must be placed in such a way that does not interfere the information provided by the manufacturer in the original container. 4. Labelling of Lines It is necessary to identify all tubes or equipment lines used to administer medicaments, monitoring, etc. corresponding to high-risk of administration routes (epidural, intrathecal and intraarterial). 4.1. Size and Characteristics Labels must have 2 symmetrical sides of, at least, 40 mm long and 20 mm wide joined by an isthmus of 20 mm up to 30 mm long and 10 mm wide, so the isthmus can “hug” the line while the back of the 2 main sides can be joined and remain as a flag. The surface of both back of labels must stick. 4.2. Color The background colors to identify each administration route will be the following: Epidural route Yellow Yellow Pantone Intrathecal route (spinal) Yellow Yellow Pantone Intraarterial route Red 1787 Pantone Red 15 The text must be black, and Arial letter with a size of, at least, 12 points the typographic characters. 4.3. Information contained in the label The label must offer the following text: Epidural route EPIDURAL Intrathecal route (spinal) ESPINAL Intraarterial route 4.4. IntraARTERIAL Label placement The line must be identified with two labels: one in the proximal (patient) side and the other in the distal one (container). In the case an infusion pump is used, then it is convenient to place another label just under or over the infusion device. 16 REFERENCES 1. Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors. Aspden P, Wolcott JA, Lyle Bootman J, Cronenwett LR, editors. Preventing medication errors. Institute of Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2007. 2. Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices. Creation of a better medication safety culture in Europe: Building up safe medication practices. Marzo 2007. Disponible en:http://www.coe.int/t/e/social_cohesion/socsp/Medication%20safety%20culture%20report%20E.pdf 3. Otero López MJ. Errores de medicación y gestión de riesgos. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2003; 77: 527-40. 4. Taxis K, Barber N. Ethnographic study of incidence and severity of intravenous drug errors. Br Med J. 2003; 326: 684-8. 5. Taxis K, Barber N. Causes of intravenous medication errors: an ethnographic study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003; 12: 343-8. 6. Cousins DH, Sabatier B, Begue D, Schitt C, Hoppe-Tichy T. Medication errors in intravenous drug preparation and administration: a multicentre audit in the UK, Germany and France. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005; 14: 190-5. 7. Valentin A, Capuzzo M, Guidet B, Moreno R, Metnitz B, Bauer P, Metnitz P. Errors in administration of parenteral drugs in intensive care units: multinational prospective study. BMJ. 2009; 338: b814. 8. The Joint Commission. 2006 National Patient Safety Goals. Disponible http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/ en: 9. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Errors with injectable medications: Unlabeled syringes are surprisingly common! ISMP Medication Safety Alert! 2007; 12 (23): 1-2. Disponible en: http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20071115.asp 17 10. Promoting safer use of injectable medicines. National Patient Safety Agency, 2007. Disponible en: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59812 11. Cuestionario de autoevaluación de la seguridad del sistema de utilización de los medicamentos en los hospitales. Adaptación del ISMP Medication Safety SelfAssessment for Hospitals, por el Instituto para el Uso Seguro de los Medicamentos (ISMP-España). Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2007. Disponible en: http://www.msc.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/excelencia/cuestionario_seguri dad_sistema_medicamentos_hospitales.pdf 12. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. National Recommendations for user-applied labelling of injectable medicines, fluids and lines. August 2010. Disponible en: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/PriorityProgram06_UaLIMFL 13. Joint Commission. Tubing misconnections—a persistent and potentially deadly occurrence. Sentinel Event Alert. 2006 Apr 3. Disponible en: http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_36_tubing_misconnections% E2%80%94a_persistent_and_potentially_deadly_occurrence/ 14. World Health Organization. World Alliance for Patient Safety. Avoiding catheter and tubing mis-connections. Patient Safety Solutions. Solution 7. May 2007. Disponible en: http://www.ccforpatientsafety.org/common/pdfs/fpdf/presskit/PS-Solution7.pdf 15. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory. Tubing misconnections: making the connection to patient safety. Pa Patient Saf Advis. 2010 Jun; 7 (2): 41-5. 16. Webster CS, Merry AF, Larsson L, MacGrath KA, Weller J. The frequency and nature od drug administration error during anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001; 29: 494-500. 17. US Pharmacopeia. Medication errors in the perioperative environment. USP Patient safety CAPSLink. 2003 March; 1- 5. 18 18. Abeysekera A, Bergman IJ, Kluger MT, Short TG. Drug error in the anesthetic practice: a review of 896 reports from the Australian Incident Monitoring Study database. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60: 220-27. 19. Gordon PC. Wrong drug administration errors amongst anesthetists in a South African teaching hospital. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2004; 5: 7-8. 20. Bartolomé Ruibal A, Gómez-Arnau Díaz-Cañabate JI, Santa-Úrsula Tolosa JA, Marzal Baró JM, González Arévalo A, García del Valle Manzano S, et al. Utilización de un sistema de comunicación y análisis de incidentes críticos en un servicio de anestesia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2006; 53: 471-78. 21. Errando CL, Blasco P. Errores relacionados con la administración de medicamentos en anestesiología, reanimación-cuidados críticos y urgencias. Factores para mejorar la seguridad y calidad. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2006; 53: 397-99. 22. Jensen LS, Merry AF, Webster CS, Weller J, Larsson L. Evidence-based strategies for preventing drug administration errors during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2004: 59: 493504. 23. Merali R, Orser BA, Leeksma A, Lingard S, Belo S, Hyland S. Medication safety in the operating room: teaming up to improve patient safety. Healthcare Quaterly. 2008; 11: 5457. 24. Glavin RJ. Drugs errors: consequences, mechanisms, and avoidance. Br J Anaesth. 2010; 105: 76-82. 25. Eichhorn JH. APSF hosts medication safety conference. Consensus group defines challenges and opportunities for improved practice. APSF Newsletter. 2010; 25 (1): 1- 8. 26. Mellin-Olsen J, Staender S, Whitaker DK, Smith AF. The Helsinki Declaration on patient safety in Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesth. 2010; 27: 592-97. 26 bis. Mellin-Olsen J, Pelosi P, Van Aken H. Declaración de Helsinki sobre la seguridad de los pacientes en Anestesiología (Versión extractada en español de 26). Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2010; 57: 594-95. 19 27. Working Party on Safety and Quality of Care. Guidelines for safety and quality in anaesthesia practice in the European Union. Eur J Anaesth. 2007; 24: 479-82. 28. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Statement on the labeling of pharmaceuticals for use in Anesthesiology. October 2009. Disponible en: http://www.asahq.org/ForHealthcare-Professionals/Standards-Guidelines-and-Statements.aspx 29. American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D4774-06 Standard specification for user applied drug labels in Anesthesiology. Disponible en: http://www.astm.org/Standards/D4774.htm 30. International Organization for Standardization. User-applied labels for syringes containing drugs used during anesthesia. Colours, design and performance. ISO 26825:2008. Disponible en: http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=4381 1 31. Canadian Standards Association. Standard for user-applied drug labels in anesthesia and critical care, CAN/CSAZ264.3; 1998. Disponible en: http://www.shopcsa.ca/onlinestore/electronic_catalogue/English_Catalogue.pdf 32. Canadian Anaesthesiologist´s Society. Guidelines to the practice of Anesthesia. Can J Anesth. 2010; 57: 58-87. Disponible en: http://www.cas.ca/English/Page/Files/97_Standards_2010EN.pdf 33. User- applied labels for use on syringes containing drugs used during anaesthesia, AS/NZS 4375: 1996, Joint Australian/New Zealand standard, prepared by joint technical committee HT/7. Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 1996; 1-5. Disponible en: http://www.hunter.health.nsw.gov.on/ducs/CGU_02_08.pdf 34. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the safe administration of injectable drugs in Anaesthesia, PS51 (2009). Disponible en: http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/pdf/PS51.pdf. 20 35. Royal College of Anaesthetists, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, Faculty of Accident and Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care Society. Syringe labelling in critical care areas. RcoA Bulletin 19; May 2003: 953. 36. Royal College of Anaesthetists, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, Faculty of Accident and Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care Society. Syringe labelling in critical care areas. June 2004 update. Disponible en: http://www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines/docs/syringelabels(june)04.pdf 37. Société Française d´Anesthésie et de Réanimation. Prévention des erreurs médicamenteuses en anesthésie. Recommandations de la Sfar. Novembre 2006. Disponible en: http://www.sfar.org/_docs/articles/preverreurmedic_recos.pdf 38. SIAARTI Study Group on Safety in Anesthesia and Critical Care. Syringe labelling in anesthesia and intensive care. Disponible en: http://www.siaarti.it/documenti/pdf_doc/file_4.pdf. 39. Birks RJS, Simpson PJ. Syringe labelling- an international standard. Anaesthesia. 2003; 58: 515-19. 40. Shannon J, O´Riain S. Introduction of “international syringe labelling” in the Republic of Ireland. Ir J Med Sci. 2009; 178: 291-96. 41. Wheeler SJ, Wheeler DW. Medication errors in anaesthesia and critical care. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60: 257-73. 42. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Color-coded syringes for anesthesia drugs: use with care. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! 2008; 13 (25): 1-2. 43. Report 5 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A-04) full text. The role of color coding in medication error reduction. Chicago (IL): American Medical Association; 2004. Disponible en: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/no-index/about-ama/13662.shtml 44. Filiatrault P, Hyland S. Does colour-coded labeling reduce the risk of medication errors? CJHP. 2009; 62: 154-56. 21 45. ISMP-Canada. Operating room medication safety checklist. Version 2. Toronto: ISMPCanada, 2009. 46. National Patient Safery Agency. Neuraxial Update. Issue 01 August 2010. Disponible en: http://www.patientsafetyfirst.nhs.uk/ashx/Asset.ashx?path=/Medicationsafety/NPSANeuraxial%20Update%20Newsletter-Aug%202010.pdf 47. National Patient Safety Agency. Supporting information for rapid response report NPSA/2008/RRR06. Problems with infusions and sampling from arterial lines, 28 July 2008. Disponible en: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59891 48. National Patient Safety Agency. Patient Safety Alert 19. Promoting safer measurement and administration of liquid medicines via oral and other enteral routes. 28 March 2007. Disponible en: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59808 49. Instituto para el Uso Seguro de los Medicamentos. Lista de medicamentos de alto riesgo. ISMP-España. Enero 2008. Disponible en: http://www.ismpespana.org/ficheros/Medicamentos%20alto%20riesgo.pdf 50. Wheeler DW, Remoundos DD, Whittlestone KD, Palmer MI, Wheeler SJ, Ringrose TR et al. Doctor´s confusion over ratios and percentages in drug solutions: the case for standard labelling. J R Soc Med. 2004; 380-83. 51. Wheeler DW, Carter JJ, Murray LJ, Degnan BA, Dunling CP, Salvador R et al. The effect of drug concentration expression on epinephrine dosing errors. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 148: 11-14. 52. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. FDA and ISMP lists of look-alike drug name sets with recommended tall man letters. Disponible en: http://www.ismp.org/tools/tallmanletters.pdf 53. Hellier E, Edworthy J, Derbyshire N, Costello A. Considering the impact of medicine label design characteristics on patient safety. Ergonomics. 2006; 49: 617-30. 22 54. Filik R, Purdy K, Gale A, Gerret D. Labeling of medicines and patient safety: Evaluating methods of reducing drug name confusion. Human Factors. 2006; 48: 39-47. 55. Otero López MJ, Martín Muñoz R, Domínguez-Gil Hurlé A. Abreviaturas, símbolos y expresiones de dosis asociados a errores de mediccaión. Farm Hosp. 2004; 28: 141-44. Disponible en: http://www.ismp-espana.org/ficheros/abreviaturas.pdf The Internet references have been consulted in different times from November to the end of December 2010.