* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download How the shape of ocean floors can affect speed and height of tsunami

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

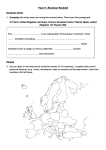

How the shape of ocean floors can affect speed and height of tsunami By Nigel Hawkes Times Online , December 27, 2004 Tsunami: Science THE long arch of Sumatra and Java, sweeping like a crescent across the north of the Indian Ocean, is one of the most active geological regions in the world. Close by, in the Sundra Strait between Sumatra and Java, is Krakatoa, the scene in 1883 of one of the world’s most catastrophic volcanic eruptions, when an entire island virtually disappeared. Yesterday the region was the setting for an earthquake and tsunami more frightening than anything dreamed up for a Hollywood disaster movie. The cause lies deep beneath the ocean, where two of the great tectonic plates that carry the continents around the Earth collide. The Indian-Australian plate slides under the Philippine plate in a “subduction zone” 750 miles long and more than 300 miles wide. The movement is jerky, as the submerging plate tends to drag the upper plate down with it. But as pressure builds, the upper plate breaks free, springing back to its original position. Yesterday’s movement was just 16½ yards at a depth six miles below the seabed, but it was more than enough. The seabed lifted, displacing the ocean. The water had to find somewhere to go, so began to flow outwards in a huge wave, or tsunami. Dr Roger Musson, a seismologist with the British Geological Survey in Edinburgh, said that similar events had been taking place in the region for several million years and would happen again over the next few million years. “The effect of the earthquake is like throwing a stone in a pond, except that you are throwing it from below. You get the equivalent of a splash and water is displaced with waves spreading outwards,” he said. Over the ocean, the waves of a tsunami are small, probably no more than a few centimetres to a metre high. Fisherman 20 miles out at sea barely notice their passage. Their speed depends on the depth of the water, but is typically several hundred miles an hour. The deeper the water, the faster the waves travel and at the bottom of the deepest ocean they can keep pace with a jet aircraft. As yesterday’s tsunami approached the coasts of Sri Lanka, Indonesia, India, Thailand, Malaysia and the Maldives, it slowed. The more it became compressed, the more it grew in height. As it reached the shore it grew into a monster. “The scale of the waves will vary from place to place, depending on the topography of the coast,” Dr Musson said. “If you have a narrow inlet, the water stacks up and you get higher waves. These are not normally more than one or two metres high but we are getting reports of yesterday’s being up to ten metres. “What does the damage is the speed and force of the water. It can be moving at 300mph across the open ocean, and then slower as the water gets shallower. “By the time it hits the coast it will be doing tens of miles an hour. The water will sweep in and collect everything in its way. It will drag it across the land and then recede. “The effect can be incredibly devastating. The land will be scoured of everything that was previously there. They can wipe out whole villages, leaving just gravel in their wake.” The first signs of the earthquake were picked up at the British Geological Survey’s Edinburgh headquarters just after 1am yesterday. It was clear that it was a very big earthquake, measuring a magnitude of 8.9, the fifth largest since 1900 and the largest since 1964. Yesterday’s witness descriptions vary widely varied, depending on where they came from. Tsunami is the Japanese word for “harbour wave”, reflecting the fact that in a natural harbour or inlet the effects can be greatly magnified. Small, steeply sloped islands suffer the least damage. Coral islands are often protected by their barrier reefs. But low- lying islands suffer a far greater “runup” of the water, and much greater damage. In the Pacific a tsunami warning system has been established. Seismic stations, the US Geological Survey, and other international sources measure earthquakes as they occur and, if they are in places where a tsunami might result, issue warnings. These include the predicted arrival times at places the tsunami is capable of reaching. Local authorities are then responsible for implementing evacuation plans, while radio and TV are used to warn the public to move to higher ground. International scientists have been calling for a tsunami warning system to be set up by governments around the Indian Ocean, Dr Musson said. “They have one in the Pacific. But governments have not invested in one for the Indian Ocean, partly because events like this are far less common. You need political will and governments (that are) prepared to stump up the cash.” Dr Musson cautioned that the region was not yet out of danger. He said: “There could be more tidal waves coming from earthquake aftershocks. The aftershocks are still happening. There could be a 7 or a 7.5 still to come.”