* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The SCALP

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

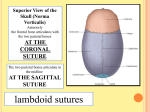

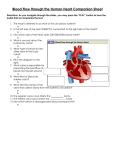

The SCALP By Prof. Dr. Muhammad Imran Qureshi The “SCALP” includes FIVE layers external to the Calvaria. These are: S: Skin & Superficial Fascia C: Connective Tissue A: Aponeurosis (Epicranial) L: Loose areolar Tissue P: Pericranium (Periosteum) Figure 1: Layers of the SCALP The Skin; thick with many close set hair follicles and their associated sebaceous and sweat glands, firmly joined to the next deeper layer. The Superficial Fascia consists of very dense Connective Tissue and contains superficial nerves and vessels in abundance. The epicranius or Occipitofrontalis muscle is made up of two occipitalis and two frontalis muscles, with their intervening Aponeurosis, called the galea Aponeurotica. (Laterally auricular muscles are also part of this layer) Figure 2: The Dangerous area A Loose connective tissue layer. (The danger area of the scalp). Contains a few small vessels. The nature of this layer permits easy movements of the layers above…which move as a unit. The Pericranium (Periosteum) of the calvaria. Except at sutures, it is poorly fixed to bone by connective tissue fibres (Sharpey’s fibres) The skin is inseparably attached to the dense connective tissue which makes up the superficial fascia. This layer is in turn firmly attached to the Epicranius muscle (comprising of the two frontalis and two occipitalis muscles and the intervening Galea Aponeurotica) When the epicranius contracts, movement occurs in all three layers. Deep to the epicranius is the layer of Loose connective tissue upon which the epicranius moves. It is here that separation of scalp from pericranium may occur following laceration. Thus, large areas of lacerated scalp may hang grossly over the face or neck, held by an undamaged pedicle. The entire scalp can be pulled off if long hair is caught by power machinery. Figure 3: Coronal Section of the SCALP It is known as the danger area because the extravasated blood spreads within it with ease to form a puddle. To understand where it spreads, you must have the knowledge of the attachment of the overlying epicranius muscle. Each Occipitalis arises from the Superior Nuchal line and inserts into the Galea Aponeurotica anteriorly. Each Frontalis muscle is attached to the Galea Aponeurotica posteriorly but has no bony attachment as it descends into the region of the forehead; Instead, it intermingles with the fibres of the Orbicularis Oculi, and some of its fibres rather attach to the skin of the forehead and upper eye lid (Panniculus Carnosus) Figure 4: Details of the Layers of the SCALP Any material of a fluid nature, e.g. Extravasated blood, in the loose layer cannot track into the neck, because of the firm attachment of the epicranius to the Superior Nuchal line. However, it can and does track into the upper eyelids and forehead, resulting into TWO black eyes. The scalp covering the lateral side of the head i.e. over the temporal fascia undergoes changes which hinder and even prevent the passage of extravasated blood towards the zygomatic arch. In the coronal section of the scalp and skull, while there is no change in the skin as one approaches the zygomatic arch, the superficial fascia becomes less dense; the Galea aponeurotica disappears except for a weak layer of connective tissue difficult to trace to the zygomatic arch, and the loose layer becomes fairly dense and is lost as a distinct entity. Thus, the element of danger inherent in looseness is largely removed. Figure 5: Attachments of the Frontalis & Occipitalis to the Galea Aponeurotica Nerve Supply of the SCALP Anterior to the Auricle: Supraorbital and Supratrochlear branches of the Ophthalmic division of Trigeminal Nerve (Va). Zygomaticotemporal branch of the Maxillary division of Trigeminal Nerve (Vb), and the Auriculotemporal branch of the Mandibular division of Trigeminal Nerve (Vc) Figure 6: Lateral attachments of the SCALP Posterior to the Auricle: Lesser Occipital nerve (C2) from the Cervical plexus. Greater Occipital and Third Occipital from the posterior rami of the second and third cervical nerves. All of these nerves with the exception of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves run most of their courses in the dense connective tissue. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves run in the loose areolar tissue layer deep to the frontalis muscle for a considerable distance, but ultimately, Figure 7: Nerve Supply of the SCALP they pierce the frontalis muscle to enter the dense connective tissue. Infections in the dense connective tissue elicit much pain because this tissue resists swelling and thus exerts pressure on the nerves lying within it. Arterial Supply of the SCALP Each side of the scalp receives FIVE arteries: Two small ones, the supratrochlear and supraorbital, which stem indirectly from internal carotid and Three large ones, the Superficial Temporal, the Posterior Auricular and the Occipital, which are direct branches of the external carotid. These five branches not only anastomose with each other but also with those of the opposite side. These anastomoses assume great importance after ligation of the common or external carotid artery of one side. Figure 8: Arterial Supply of the SCALP In scalp lacerations, blood may spurt from both ends of the cut arteries due not only to anastomosis but also to the fact that these anastomosing arteries course in dense connective tissue which blends with their adventitia and actually tends to hold them when they are cut. Because of widespread anastomoses of arteries, scalp separations are easily restored unless the loose flap of scalp has a very small pedicle. Venous Drainage of the SCALP Venous channels accompany the five paired arteries BUT There are veins which connect scalp veins to Cranial venous sinuses (Emissary Veins) Emissary veins are the veins that pass through various foramina and openings in the cranial wall and establish anastomoses between the sinuses of the dura inside and veins on the exterior of the skull. Figure 9: Venous Drainage of the SCALP These veins are not confined to the scalp. They also pass through the foramina in the base of the skull, bony orbit etc. They do not have valves. The blood therefore, may flow either into or out of the venous sinuses. The emissary veins most intimately related to the scalp are two parietal, two mastoid and indirectly the ophthalmic veins. The two parietal emissary veins pass through canals in the parietal bones, located on either side of the Sagittal suture, about an inch anterior to the lambda. The mastoid emissary veins are located on either side of the skull. They pass through the mastoid foramen which lies posteromedial to the mastoid notch. They communicate the sigmoid sinus with the Occipital and posterior auricular veins. Figure 10: Venous anastomoses between the veins of the Face with veins of the SCALP & Cavernous Sinus Indirect communication may be established between the Supraorbital and supratrochlear veins of the scalp and the Cavernous sinus through superior and inferior ophthalmic veins. Infections of the scalp may spread through these veins into the meninges causing meningitis. Besides, there are Four pairs of Diploic veins that run in the Diploë. They not only anastomose with one another but also with the superficial veins of the scalp and with the dural venous sinuses. Figure 11: Doploic Veins Figure 12: Summery of the Nerve & Arterial Supply of the SCALP