* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download update on sexually transmitted infections

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Diagnosis of HIV/AIDS wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology of syphilis wikipedia , lookup

Microbicides for sexually transmitted diseases wikipedia , lookup

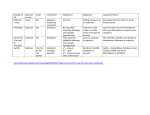

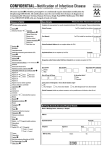

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

National Medicines Information Centre VOLUME 18 NUMBER 2 2012 ST. JAMES’S HOSPITAL • DUBLIN 8 TEL 01-4730589 or 1850-727-727 • FAX 01-4730596 • www.nmic.ie update on sexually transmitted infections The incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), which are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, is increasing It is important to consider sexual health in all patients and to ask about sexual history in patients with risk factors for STIs Patients frequently have >1 STI present; the diagnosis of a STI should prompt a search for others that may be asymptomatic Partner notification is an important aspect of STI management, which may require referral to a specialist service INTRODUCTION Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) present a major public health problem and are a major cause of acute illness, infertility, long-term disability and death worldwide.1-3 Early diagnosis and treatment of STIs can cure and prevent complications including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), urethritis, infertility, arthritis and meningitis.3,4 The global incidence of STIs is rising;1,5 since the 1990s the EU (including Ireland) has experienced significant increases in the incidence of STIs, especially genital chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis.2,6-8 STIs are frequently asymptomatic and an additional concern is that there is increasing antimicrobial resistance to some STIs, in particular gonorrhoea.3,9-13 The increased incidence of STIs may reflect an increase in unsafe sexual behaviour, however it may also be due to increased testing, better diagnostics and more reporting.8 Sexual health is an important aspect to consider for all patients. In 2011, 11,000 cases of STIs were notified in Ireland, as follows: genital chlamydia (51%), ano-genital warts (16%), genital herpes simplex (9%), gonorrhoea (7%) syphilis (6%), trichomoniasis (0.5%) and non-specific urethritis (10%).6 HIV became a notifiable disease in September 2011.14 This bulletin will review the commonest notifiable STIs; a future bulletin will review the management of HIV. Risk factors for STIs Certain patient groups are more at risk of acquiring a STI (see Table 1). A recent Irish study found that there was a lack of awareness amongst young people (17-34 years) of symptoms suggestive of STIs, and that there were significant levels of high risk behaviour.15 While young age is a risk factor, it is important to be aware that STIs are not only confined to young people.16 Healthcare professionals often do not discuss risky sexual behaviour and STI prevention with middle-aged and older adults.4 The incidence of STIs in those >50 years, has more than doubled in the last decade,16,17 due to factors including changing attitudes in society, new relationships, international travel, the use of drugs for erectile dysfunction and the misconception that condoms are only for contraception.4,5,16-18 Patients frequently have >1 STI present; the diagnosis of a STI should prompt a search for others that may be asymptomatic.5 Table 1: Risk factors for acquiring a STI 5 • • • • • Aged <25 years More than 2 sexual partners in the previous year A previous STI No/infrequent/inconsistent condom use Living in an area of high STI prevalence (generally, urban areas) • Visiting an area of high STI prevalence (e.g. engaging in unprotected sex in certain overseas countries) • Men who have sex with other men • Certain minority ethnic groups • Those who buy or sell sex • The sexual partners of all of the above Assessment for STIs While many patients attend specialist STI clinics for testing, patients with STIs may also present to non-specialist settings and all clinicians should be aware of the appropriate management of a patient with a STI.5 Patients with STIs are also seen in primary care;1,2 services may range from testing and referring positive cases to specialist services, to managing uncomplicated cases depending on the clinical situation.5 Certain STIs (in particular syphilis) should be referred to a specialist setting.19 It is also important to note that partner notification is an important aspect of STI management; this may require referral of the patient to a specialist service, (which has a multidisciplinary structure). A sexual health history should be incorporated into the evaluation of patients, as detailed in Table 2.19 Table 2: Sexual history19 Symptom history It is important to think of the possibility of STIs. There are many symptoms of STIs, which include the following: Men • Urethritis can present with urethral discomfort/itch, dysuria, discharge, epididymo-orchitis, reactive arthritis, conjunctivitis (autoinoculation) Women • Cervicitis can present with intermenstrual bleeding, post coital bleeding, deep dyspareunia, lower abdominal pain, ophthalmia neonatorum • Pelvic inflammatory disease – as above plus ectopic pregnancy and infertility • Vaginal infections – vaginal discharge, itch, soreness Medical history • Past medical history (including STIs) • Medication (including illicit drugs) • Allergy • Obstetric/gynaecological history for women Partner history • When was the last sexual encounter? • Who with? (traceable or not? male or female? overseas?) • What sort of sex (oral, vaginal, anal?) • Were condoms used for all contacts? • Does the partner have a history of previous STIs and/or any symptoms? • How many partners over last 3 months? Patients with STIs can present in a variety of ways; they may be symptomatic or asymptomatic presenting with an unrelated problem (belonging to a high risk group) or requesting to be tested for a STI.5 Contraceptive consultations provide an excellent opportunity to enquire about sexual health and to consider offering STI testing. Taking a sexual history involves personal and sensitive issues that can cause stress to the patient, and requires a sensitive approach. Examination should include the genital area and the oral and perianal areas, as indicated by the patients’ history. For women with a suspected STI, a vaginal examination using a speculum should be undertaken (a self obtained vaginal swab can be used to test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea in asymptomatic women).20 Clinicians should consider the need for a chaperone during an intimate examination. Investigations include testing for (1) chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomonas in patients with genital discharge, (2) syphilis and herpes in patients with genital ulcers and (3) chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, HIV and hepatitis B in asymptomatic patients with risk factors for STIs.21 Patients should be informed of the tests being undertaken. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) have been developed in recent years.5 These tests detect small amounts of the RNA and DNA of organisms and can be extremely sensitive and specific. Unlike culture methods they do not require organisms to remain viable, therefore urine samples or self-obtained swabs can be stored and transported to the laboratory at ambient temperatures. Contact should be made with the local laboratory to determine which tests are available and the transfer arrangements required. management of STIs The diagnosis of a STI often causes considerable distress to the patient and management should include the following: information on the natural history of the infection, advice on how the STI is transmitted, the complications of not treating the infection, the importance of their partners being evaluated and treated and the need to abstain from sexual intercourse (including oral) until therapy is completed.19,20 Patients and their partner/s should be tested for other STIs including HIV and hepatitis B. Every STI consultation is an opportunity for preventive education including the importance of the use of condoms to prevent STIs and that the fewer the number of sexual partners, the lower the risk of STI. Table 3 summarises the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of the common STIs. In addition, vaccination for hepatitis A and B should be offered to patients who are intravenous drug users and men who have sex with men (MSM). Non-specific urethritis is a diagnosis of exclusion after gonorrohoea and chlamydia have been excluded; many organisms can cause it including Trichomonas vaginalis, ureaplasma, herpes and mycoplasma.19 Medical practitioners are required to notify STIs to the Medical Officer of Health/Director of Public Health for the area of residence of the patient, using the notification of infectious diseases form (available on www.hpsc.ie). The Society for the Study of Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Ireland is producing a guidance document on the management of STIs for healthcare professionals, which will provide more detailed information on their management.22 Chlamydia Trachomatis Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis) genital infection is the most common curable, bacterial STI worldwide.14,23-25 Irish figures, similar to other countries, report an overall prevalence of C. trachomatis in up to 5% of asymptomatic women and a higher prevalence (11%) in those aged < 25 years.14,15,25,26 The clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated infection are summarised in Table 3. There has been an increase in the number of reported cases of chlamydia in Ireland in recent years;23 risk factors for infection include age < 25 years, new sexual partner or > one sexual partner in the last year, prior chlamydial infection and lack of consistent use of condoms.23,27,28 Chlamydia is a major public health problem, which is frequently asymptomatic in men (50%) and women (70%);2,24,27 two thirds of sexual partners of chlamydia-positive individuals are also chlamydia positive.27 C. trachomatis is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in up to 40% of infected untreated women, which can lead to ectopic pregnancy and tubal factor infertility.23,24,27 The risk of developing PID increases with each recurrence of infection.27 Other complications include neonatal transmission (neonatal conjunctivitis, pneumonia), epididymo-orchitis, and sexually acquired arthritis (more common in men);14,27 it also facilitates the transmission of HIV in both men and women.23,24 Chlamydia screening programmes are in place in some countries, however evidence to support their effectiveness has been questioned.24,29,30 Results of a recent Irish study did not support the establishment of an opportunistic screening programme in Ireland.24,31 A test of cure is not routinely recommended but should be performed in pregnancy or if non-compliance or re-exposure is suspected.27 ano-Genital warts Genital warts are caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV) of which there are > 100 subtypes.2,20,32,33 The majority of HPV infections are asymptomatic or subclinical.20,33,34 The clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated infection are summarised in Table 3. Studies suggest that up to 2% of the population up to 49 years have had genital warts.35 Most ano-genital warts are caused by non-oncogenic HPV types 6 and 11 (90%),20,34,35 however some lesions may contain oncogenic types associated with genital tract dysplasia and cancers (e.g. types 16 and 18).20,33,36 Those at risk of genital warts include young patients (highest incidence in 20-29 years), MSM and patients with HIV.21,34,35 Consistent use of condoms decreases the risk of genital warts by 70%.33-35 Recent evidence suggests that patients with genital warts have a long-term increased risk of anogenital cancers and head and neck cancers.37 Treatment of genital warts is encouraged as they are highly infectious,20 however a minority of cases resolve without treatment.35 All treatments have significant failure and relapse rates and may involve discomfort and local skin reactions. Podophyllotoxin and imiquimod are contra-indicated in pregnancy or lactation.38-40 Imiquimod is not recommended for urethral, intra-vaginal, cervical, rectal or intra-anal warts and/or in tissues with open wounds.40 Local skin reactions are common; imiquimod should be used with caution in patients with autoimmune conditions and in un-circumcised men with foreskin associated warts.40 The impact of the introduction of the HPV vaccination for adolescent girls on the incidence of ano-genital warts, cervical cancer, other lower ano-genital tract cancers and other HPV associated cancers is awaited. genital Herpes Simplex Genital herpes is equally likely to be caused by herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1, the usual cause of oro-labial herpes) or herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2, historically associated with sexual transmission).21,32,41 The majority of infections are acquired subclinically.32,41 Those at increased risk of infection include younger patients, MSM and patients with HIV.21 HSV is the most common STI in HIV patients.41 Following primary infection, the virus becomes latent in local sensory ganglia, periodically reactivating to cause symptomatic/asymptomatic lesions and infectious viral shedding.41 Genital infection with HSV-1 has a milder natural history than infection with HSV-2 and is associated with less frequent symptomatic recurrences and asymptomatic shedding.21,41 Condoms may be partially effective in preventing acquisition of HSV, especially in preventing transmission from infected males to their female sex partners.41 The clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated infection are summarised in Table 3. Many patients with symptomatic HSV may not have the classical lesions as described and serology may be helpful in situations including recurrent genital disease of unknown cause and investigating asymptomatic partners of patients with genital herpes, including pregnant women.41 Complications of HSV include autonomic neuropathy (resulting in urinary retention), autoinoculation to fingers and adjacent skin and aseptic meningitis. Recurrent HSV tends to be mild and self-limiting and management is on an individual basis.19,41 The patient may present with healing lesions and it may be appropriate to prescribe antiviral treatment (aciclovir or valaciclovir) for the next episode.41-43 The decision to start continuous suppressive therapy, which should be discontinued after a maximum of 12 months, needs to take into account the frequency of attacks (> 6 attacks annually) and the costs and inconvenience of treatment.19,41 While the risk of neonatal transmission is very low, pregnant women with a history of genital herpes should inform their obstetrician.21,41 Perinatal transmission, associated with disseminated HSV (which is rare) in the neonate, is most likely to occur following vaginal delivery after a first episode maternal genital HSV infection in the final trimester.19,21 The risk of neonatal transmission is much lower with recurrent HSV lesions or asymptomatic infection. Gonorrhoea Gonorrhoea is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which represents 88 million of the estimated 448 million new cases of curable global STIs occurring annually.9 Although not as common as other STIs, there has been an increase in the incidence of gonorrhoea notified in Ireland in recent years.6,44 The prevalence of gonorrhoea is low in the general population but the risk is increased in MSM.45 The clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated infection are summarised in Table 3. Frequently the infection is asymptomatic; asymptomatic carriers are more likely to transmit the disease than people with overt infections.9 Untreated or inadequately treated gonorrhoea results in complications including PID, epididymo-orchitis, prostatitis, arthritis, infertility and conjunctivitis.32,46 Patients with genital gonorrhoea are frequently co-infected with C. trachomatis (35% men and 41% women).32,46 Gonorrhoea is also known to facilitate the transmission of HIV infection.45 Currently of concern is the resistance of N. gonorrhoeae to third generation cephalosporins; emerging resistance have been reported in countries including the US, Australia, Norway and the UK.9,11,13 Referral to a specialist STI service should be considered for patients diagnosed with gonorrhoea and is recommended for patients with penicillin allergy for appropriate treatment, testing for other STIs and partner notification.22 A test of cure is recommended in all cases. Syphilis Syphilis is caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum.14 It is a complicated infection and patients diagnosed with syphilis should be referred to a specialist service for management.14,19 Although less common than other STIs, similar to other developed countries, an increase of syphilis has been noted in recent years in Ireland.47-50 The highest rates of syphilis occur in MSM;47,48,50,51 an additional risk factor is HIV infection.51 Syphilis however may also occur in heterosexual men and in women.50 Syphilis has an incubation period of up to 90 days and is usually transmitted during sexual contact, however transmission may occur during pregnancy and via infected blood products.52 The clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of syphilis are summarised in Table 3. Syphilis can be classified into early (primary, secondary and early latent <2 years of infection) and late (late latent >2 years of infection and tertiary).52 Syphilis is known as “the great pretender”; it can mimic many inflammatory conditions including uveitis.53 Syphilis (+/- HIV seroconversion) should be considered in MSM presenting with a rash and in all patients presenting with a genital ulcer.20 It is important to be aware of the signs and symptoms associated with syphilis;54 if left untreated, it can lead to serious sequelae including cardiovascular syphilis and neurosyphilis50 and during pregnancy, to conditions including polyhydramnios, miscarriage, pre-term labour and stillbirth.52 The immune response to syphilis involves production of antibodies to a broad range of antigens including specific [e.g. T. pallidum enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for immunoglobulin (Ig) G or IgM, T. pallidum haemagglutination test (TPHA) and T. pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA)] and non-specific [e.g. rapid plasma regzain test (RPR)] treponemal antibodies.52,55 The first response to infection is the production of specific treponemal IgM (detected towards the end of the second week of infection) and IgG which appear by about 4 weeks.55 Interpretation of positive serology for syphilis requires specialist advice/ referral and a detailed history from the patient (including symptoms, treatment and previous test results).20,22 Positive tests should always be repeated on a second specimen to confirm the results,52,55 while serology should be repeated a few weeks following a negative test if there is a high clinical suspicion of syphilis.19 Trichomoniasis Trichomonos vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan which is found in the vagina, urethra and paraurethral glands in women (may be carried for months or years)19 and usually in the urethra in men.56 In adults transmission is almost exclusively sexually transmitted.56 There is evidence that trichomonos infection may enhance HIV transmission and there is concern that it may be associated with pregnancy complications.56,57 A test of cure is recommended in all cases.22 Table 3: Clinical manifestations, testing and treatment of the common STIs STI ***Contact tracing is an important aspect in the management of STIs*** Clinical manifestations Diagnosis Chlamydia (14,27,28,58) Females – (70% asymptomatic) post-coital (PCB) or (Chlamydia intermenstrual bleeding (IMB), lower abdominal pain, trachomatis) purulent vaginal discharge, mucopurulent cervicitis +/contact bleeding, dysuria. Males – (50% asymptomatic) urethral discharge, dysuria. Rectal: infections usually asymptomatic but may cause anal discharge and anorectal discomfort. Pharynx: infections are asymptomatic and uncommon. Genital warts Single or multiple warts in areas including the vulva, (20,33,38-40) urethra, shaft of penis or scrotum, cervix, vagina, and Human papilloma perianal area. virus Warts on the moist non-hair bearing skin tend to be soft and non-keratinised and those on the dry hairy skin firm and keratinised. NAAT ** of first void urine in men and women (patients should hold urine for at least one hour); a cervical swab or patient-taken vulvo-vaginal swab in women can also be used. Rectal +/- pharyngeal swabs if indicated. Visual examination in most cases. Biopsy may be required for atypical or pigmented lesions to exclude neoplastic lesion especially in patients with HIV. Genital herpes simplex Swab from base of ulcer – for NAAT (preferred) or viral culture. Primary infection – (frequently asymptomatic), febrile illness 5-7 days, tingling/neuropathic pain in (41,42,43,59) genital area, extensive bilateral crops of genital blisters, Herpes simplex virus ulcers or fissures, lymphadenitis. type 1 and 2 Recurrent infection – usually self-limiting, unilateral ulcers (may be small and resemble non-specific erythema, erosions or fissures). Gonorrhoea Females – (50% asymptomatic), ↑ vaginal discharge, (14,45,46,60,61) lower abdominal pain/tenderness, dysuria, rarely IMB (Neisseria or PCB, mucopurulent cervicitis +/- contact bleeding. gonorrhoeae) Males – (95% symptomatic), urethral discharge +/- dysuria within 2-5 days of exposure, mucopurulent discharge commonly, rarely epididymal tenderness or balanitis. Rectal infection (anal discharge 12%) and pharyngeal infection usually asymptomatic. Syphilis NAAT of endocervical, vaginal and urethral swabs (men) and urine (men and women), rectal and pharyngeal swabs when indicated. Culture and sensitivity if possible recommended for positive NAATs prior to treatment. Diagnosis can be made by dark ground microscopy of lesions (only in specialist centres). Treatment* Azithromycin 1 gram PO stat or doxycycline 100mg PO BD for 7 days (contraindicated in pregnancy). (Test of cure not routinely required) Consider referral for specialist advice in: Pregnancy*: amoxicillin 500mg po tds x 7 days, erythromycin 500mg po bd x 14 days or azithromycin 1 gram PO stat. (Test of cure recommended) Podophyllotoxin paint/cream - apply twice daily 3 times weekly for 4-5 weeks. Imiquimod cream - apply 3 times per week (remove after 6-10 hours) for a maximum of 16 weeks. Cryotherapy applied weekly until resolution. Removal of warts under local anaesthetic – possible for pedunculated warts and small keratinised warts at accessible sites. Electrosurgery or laser treatment may be required for some lesions. Primary infection oral antiviral drugs (aciclovir, valaciclovir and famciclovir) within 5 days of the start of the episode and while new lesions are forming; saline baths, analgesia (+/topical lidocaine) prior to micturition. Hospitalisation may be required for complications including urinary retention and meningism. Recurrent infection – see text. Consider referral for specialist advice Ceftriaxone 500mg IM stat plus azithromycin 1 gram po stat. (Test of cure recommended) Refer for specialist advice in: Penicillin/cephalosporin allergy – treatment includes high dose azithromycin as a single dose or ciprofloxacin (pending sensitivity) (Test of cure recommended) Primary [~3weeks (1-90 days)] Painless chancre at Refer for specialist advice the site of inoculation. Treatment involves multidisciplinary specialist management. (Treponema Secondary [~6weeks (2-12 weeks)] includes rash Treatment decision should be made by a specialist in STI; the pallidum) (incl. extremities), mucous patches, condyloma preferred treatment includes parenteral penicillin lata, alopecia, systemic symptoms, diffuse lymphadenopathy, neurological abnormalities. Screen with serology Latent - asymptomatic, positive serology; early - <2 e.g. T. pallidum specific years, relapse likely; late >2 years, relapse improbable. EIA# Positive results to be followed up with a different Tertiary – [up to 30 years after exposure] spread treponemal test. of infection to other organs includes: neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis and gummatous syphilis. Females – (50% asymptomatic) vaginal frothy Trichomoniasis High vaginal swab (females) Metronidazole 2g orally in a single dose or metronidazole (19,56,62) discharge, vulval soreness, dysuria, vulvitis, vaginitis, ## and urethral swab for 400mg BD for 5-7 days. (Trichomonos males for direct microscopy, (Test of cure recommended) “strawberry cervix” (2%). vaginalis) culture and sensitivity. First Males - (50% asymptomatic), urethral discharge void urine (males) – culture. +/- dysuria. * - prescribers should refer to the Summary of Products Characteristics for full prescribing information; note that not all medicinal products are authorised for the indication, ** - nucleic acid amplification technique, # - enzyme immunoassay, ## - cervical cytology has high false positive (30%), need confirmation with culture from high vaginal swab (14,52,55) SUMMARY It is important to consider the sexual health of all patients and the possibility of a patient having a STI, many of which are asymptomatic. Testing for STIs is recommended for symptomatic patients and asymptomatic patients who are at risk of a STI. Patients frequently have >1 STI present; the diagnosis of a STI should prompt a search for others that may be asymptomatic. A screen for STIs should include testing for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, HIV and hepatitis B. Some patients with STIs (in particular syphilis) should be referred to a specialist setting. Partner notification is an important aspect of STI management. Medical practitioners are required to notify STIs to the Medical Officer of Health/Director of Public Health. Management should include preventive education including the importance of the use of condoms to prevent STIs and counselling as indicated. Patient information leaflets on STIs are available from the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (available on www.hpsc.ie). FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY. NOT TO BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE EDITOR List of references available on request. Date of preparation: July 2012 Every effort has been made to ensure that this information is correct and is prepared from the best available resources at our disposal at the time of issue. Prescribers are recommended to refer to the individual Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for specific information on a drug. References for Sexually Transmitted Infections Volume 18 No 2 2012 1. Miners A et al, Assessing user preferences for sexually transmitted infection testing services: a discrete choice experiment, Sex Transm Infect 2012; doi:10.1136/sextrans050215 2. A report by the Sexually Transmitted Infections subcommittee for the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Health Protection Surveillance Centre, Surveillance of STIs December 2005, downloaded form www.hpsc.ie on the 19th June 2012 3. WHO, Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections, WHO 2003; publisher http://www.who.int.elib.tcd.ie/2003 downloaded on the 2nd July 2012 4. Jeffers L, DiBartolo M, Raising health care provider awaresness of sexually transmitted disease in patients over age 50, Medsurg Nursing, November-December 2011;20(6):285290 5. Lazaro N, Management of sexually transmitted infections in non-specialist settings: practical issues, Medicine 2010;36(6):322-327 6. Health Protection Surveillance Centre, Quarterly report on Sexually Transmitted Infections in Ireland, Quarter 4, 2011 from http://www.hpsc.ie/hpsc/AZ/HIVSTIs/SexuallyTransmittedInfections/Publications/STIAnnualandQuarterlyReports/20 11/ downloaded from www.hpsc.ie on 19th June 2012 7. Health Protection Surveillance Centre, Report on Sexually Transmitted Infections in Ireland, Quarter 4 2001 & 2001 Annual Report http://www.hpsc.ie/hpsc/AZ/HIVSTIs/SexuallyTransmittedInfections/Publications/STIAnnualandQuarterlyReports/20 01/File,887,en.pdf downloaded from www.hpsc.ie on 5th July 2012 8. Cronin M, Domegan L, Incidence of STIs continues to rise in the Republic of Ireland, Eurosurveillance, October 2003, Volume 7, Issue 42 9. WHO fact sheet – Emergence of multi-drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae – Threat of global rise in untreatable sexually transmitted infections 2011; downloaded from www.who.int on the 11th July 2012 10. Lukehart S, Godornes C, Molini B, Sonnett P et al, Macrolide resistence in Tropenema pallidum in the United States and Ireland, N Engl J Med 2004;351:154-8 11. Editorial, Gonorrhoea – old disease, new threat, The Lancet June 2012;379:2214 12. Cole M, Chisholm S, Hoffmann S, Stary A et al, European surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:427-432 13. Bolan G, Sparling F, Wasserheit J, The emerging threat of untreatable gonococcal infection, N Engl J Med 2012;366(6):485-487 14. Health Protection Surveillance Centre, Epi Insight February 2012, downloaded from www.hpsc.ie on the 19th June 2012 15. O’Connell E, Brennan W, Cormican M, Glacken M et al, Chlamydia trachomatis infection and sexual behaviour among female students attending higher education in the Republic of Ireland, BMC Public Health, 2009;9:397 16. Peate I, Sexually transmitted infections in older people: the community nurse’s role, British Journal of Community Nursing;17(3): 112-118 17. Minichiello V et al, STI epidemiology in the global older population: emerging challenges, Perspectives in Public Health July 2012;132(4):178-181 18. Annonymous, Sex and the older woman, Harvard Women’s Health Watch, January 2012;46 19. Lazaro N, Sexually transmitted infections in primary care, RCGP Sex, Drugs and HIV Task Group, British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, 1st Edition 2006, published by RCGP and BASHH downloaded from www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 20. Guidelines for Managing Sexually Transmitted Infections – WA, Silver book downloaded from http://silverbook.health.wa.gov.au/default.asp?PublicationID=1 on the 12th July 2012 21. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, Sexually transmitted Infections: UK national screening and testing guidelines, August 2006, downloaded form www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 22. Personal communication Dr Fiona Lyons, Consultant GU Physician, St. James's Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland June 2012 23. A report prepared for the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Health Protection Surveillance Centre, The Need for Chlamydia Screening in Ireland, downloaded from www.hpsc.ie on the 19th June 2012 24. Health Protection Surveillance Centre and Health Research Board, Summary integrated report: Chlamydia screening in Ireland – a pilot study of opportunistic screening for genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Ireland (2007-2009), published 2012, available on www.hspc.ie on the 19th June 2012 25. McMillan HM, O’Carroll H, Lambert JS, Grundy KB et al, Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis in asymptomatic women attending outpatient clinics in a large maternity hospital in Dublin, Ireland, Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:503-505 26. Keegan H, Ryan F, Malkin A, Griffin M, Lambkin H, Chlamydia trachomatis detection in cervical PreservCyt specimens from an Irish urban female population, Cytopathology 2009;20:111-116 27. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, United Kingdom National Guideline for the management of Genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (2006), downloaded from www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 28. Geisler W, Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adolescents and adults: Summary of evidence reviewed for the 2010 centers for disease control and prevention sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, CID 2011;53(Suppl 3): S92-98 29. Low N, Bender N, Nartey L, Shang A et al, Effectiveness of chlamydia screening: systematic review, International Journal of Epidemiology 2009;38:435-448 30. Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Aghaizu A, Atherton H et al, Randomised controlled trial of screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: the POPI (prevention of pelvic infection) trial, BMJ 2010;340:c1642 31. Gillespie P, O’Neill C, Adams E, Turner K et al, The cost and cost effectiveness of opportunistic screening for Chlamydia trachomatis in Ireland, Sex Transm Infect 2012;88:222-228 32. Hayley M et al, What’s new in sexually transmitted infection management: changes in the 2010 guidelines from the centers for disease control and prevention, Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 2012;57:276-284 33. British Association for Sexual Health – Clinical Effectiveness Group, United Kingdom National Guidance on the Management of Ano-genital Warts 2007 downloaded from www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 34. Dunne E, Friedman, Datta S, Markowitz, et al, Updates on human papillomavirus and genital warts and counselling messages from the 2010 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, CID 2011;53(Suppl 3)S143-152 35. WHO, Human papilloma virus and HPV vaccines, - technical information for policy-makers and health professionals, WHO 2007 downloaded from www.who.int on the 11th July 2012 36. Menton J, Cremin S, Canier L, Horgan M et al, Moplecular epidemiology of sexually transmitted human papilloma virus in a self referred group of women in Ireland, Virology Journal 2009;6:112 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-112 37. Blomberg M, Friis S, Munk C, Bautz A et al, Genital warts and risk of cancer: a Danish study of nearly 50,000 patients with genital warts, JID 2012;205:1544-1553 38. SmPC Condyline® (podophyllotoxin) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 13th July 2012 39. SmPC Warticon® cream (podophyllotoxin) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 13th July 2012 40. SmPC Aldara® (imiquimod) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 13th July 2012 41. British Association for Sexual Health – Clinical Effectiveness Group, 2007 National Guidance for the Management of Genital Herpes downloaded from www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 42. SmPC Zovirax® (acyclovir) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 12th July 2012 43. SmPC Valtrex ® (valaciclovir downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 12th July 2012 44. Cullen G, O’Hora A, Health Protection Surveillance Centre, Poster – Sexually transmitted infections in Ireland, 2010 downloaded from www.hpsc.ie on the 11th July 2012 45. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV & Health Protection Agency, Guidance for gonorrhoea testing in England and Wales 2010 downloaded form www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 46. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, United Kingdom National Guideline for the management of gonorrhoea in adults, 2011, downloaded form www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 47. Muldoon E, Mulcahy F, Syphilis resurgence in Dublin, Ireland, Int J STD AIDS 2011;22(9):493-7 48. Hopkins S, Lyons F, Coleman C, et al, Resurgence in infectious syphilis in Ireland: an epidemiological study, Sex Transm Dis 2004;31(5):317-21 49. Hopkins S, Lyons F, Mulcahy F, Bergin C, The great pretender returns to Dublin, Ireland, Sex Transm Inf 2001,77:316-318 50. HPSC, Epidemiology of syphilis in Ireland, 2010, downloaded form www.hpsc.ie on the 7th July 2012 51. Ghanem K, Workowski K, Management of adult syphilis, Clinical Infectious Disease 2011;53(Suppl 3):S110-28 52. Kingston M, French P, Goh B, Goold P et al, UK National Guidelines on the Management of Syphilis 2008; International Journal of STD & AIDS 2008;19:729-740 53. Muldoon E, Hogan A, Kilmartin D et al, Syphilis consequences and implications in delayed diagnosis: five cases of secondary syphilis presenting with ocular symptoms, Sex Transm Infect 2012;86:512-513 54. Hunter K, Badwal J, Singh D, Fairbairn H et al, Room for improvement-syphilis; knowledge and delayed diagnosis among sexual health clinic attendees, Irish Medical Journal 2011;104(4):103-5 55. Egglestone SI, Turner AJL, Serological diagnosis of syphilis, Communicable Disease and Public Health 2000;3(3):158-162 56. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, United Kingdom National Guideline on the management of Trichomonos vaginalis (2007), downloaded form www.bashh.org on the 23rd June 2012 57. Gulmezoglu AM, Azhar M, Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD000220. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000220.pub2 58. SmPC Zithromax® (azithromycin) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 11th July 2012 59. SmPC Famvir® (famciclovir) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 12th July 2012 60. SmPC Rocephin® (ceftriaxone) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 11th July 2012 61. SmPC Ciproxin® (ciprofloxacin) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 16th July 2012 62. SmPC for Flagyl® (metronidazole) downloaded form www.medicines.ie on the 6th July 2012