* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

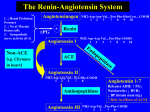

Download ACE Inhibitors and Angiotensin II

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of ACE inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of angiotensin receptor blockers wikipedia , lookup