* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Early Middle Ages (to be used with Frame)

Survey

Document related concepts

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

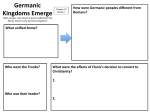

Europe After the Fall of Rome: Early Middle Ages The I. Introduction: The third successor civilization which emerged in western Eurasia in the wake of the fall of the Roman Empire is often referred to as “Western Christendom.” This successor civilization had neither the continuity of Byzantine civilization nor the spectacular initial successes of the Islamic empires. It also did not have the political unity of either Byzantium or Islam. Western Christendom initially emerged from the divided and warring tribal kingdoms which had taken over the Roman Empire in the west in the late 400s CE. II. The Germanic Successor Kingdoms: In the Early Middle Ages (500-800 CE) the nomadic Germanic tribes founded kingdoms in Italy, Gaul (France), Spain, and Britain. These kingdoms were quite different from the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire had been a world of cities where many peoples and cultures came together. The Germanic tribes were unfamiliar with cities. Their background was that of migrants and warriors. A. German Traditions: Their traditions, like those of any nomadic peoples, stressed tribal loyalty and bravery in battle. Upon their settling, the Germanic tribes did not revive the dying cities of the Roman world or preserve the humanism of Greco-Roman civilization. They had a rich oral tradition but no books. Bards recounted myths, legends, and historical events. The Germanic written language, the runic alphabet, probably devised by the Ostrogoths around 300 C.E. and based on the Greco-Italic alphabet, was used largely for inscriptions on monuments. B. Germanic Tribal States: The idea of the "state"--a central feature of Roman civilization--was foreign to the Germanic tribes. Each tribe was loyal only to its own chieftain, not to a central government that represented citizens of many nationalities. Likewise, each Germanic petty kingdom was viewed as the personal property of its ruler. Germanic kings had the right to divide up their lands and to will them to their sons. This custom led to the formation of many small, rival kingdoms and to numerous and devastating civil wars. There was no central government strong enough to bring the kingdoms together. These factors were responsible for slowing down the development of western civilization as we know it. C. Germanic Law: Roman law had been written law that applied to each citizen regardless of his/her nationality or background. The Germanic peoples, however, had no single law that applied to all the tribes. Among them, the law consisted of unwritten tribal customs: each tribe had its own laws by which members were judged. And customs varied from tribe to tribe. While Roman judges had investigated evidence and demanded proof, Germanic courts relied on trial by ordeal. In a typical ordeal, a bound defendant was thrown into a river. A defendant who sank was considered innocent; floating was interpreted as divine proof of guilt. Eventually the Germanic rulers put the customary tribal laws into writing. These codes, compiled only after the barbarian hordes invaded Rome, were called the leges barbarorum, and later, Salic Law. The first was compiled between the 5th and 9th centuries, C.E. While these laws did not apply across society as did Roman law, they did help settle successional disputes and lessened blood feuds between families. III. Early Medieval Society and Economy: During the decline of the Roman Empire, there had been a growing shift from an urban to a rural society. This tendency speeded up in the Early Middle Ages. Violence and disorder spread. Trade ground nearly to a halt. A. Toward a Rural Society: Lacking markets and protection, small farmers fled to the estates of large landowners. In many regions, those who held the land also ruled. B. Devolution of authority: Powerful landlords had their own armies and courts of law. By surrounding themselves with loyal warriors, they added to their power. Such monarchs (kings and queens) often ruled significant territory, found it increasingly difficult to control these lords. IV. Early Medieval Culture: Compared to the days of the Roman Empire, the level of civilization declined strikingly. The wonderful, cosmopolitan cities founded by the Romans were deserted. The old Roman schools that had been responsible for spreading Roman civilization and a unified culture gradually disappeared. The vast majority of people--often including the monarchs themselves--could not read or write. Yet the lamp of learning did not go out altogether as it had done with the Dorian invasions of Greece. The clergy--priests and monks--were still required to know how to read and write in order to attend to their religious duties. A. Preservation of Learning in Italy: Some scholars preserved Roman learning. The Ostrogothic king of Italy, Theodoric (r. 489-526), encouraged learning at his court. For example, Boethius, a Roman in Theodoric's service, translated some of Aristotle's writings from Greek into Latin, and wrote commentaries on ancient authors. He also turned to philosophy and wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, an apt title considering the chaotic times. The Consolation was the last great work of classical Latin. Boethius' contemporary, Cassiodorus, another Roman serving Theodoric, collected, copied, and translated ancient manuscripts. Cassiodorus is considered the first notable figure of medieval literature, because, although he wrote in Latin, it was a simpler, more fluid, and more religious in tone writing. He did much of this work after retiring to a monastery, setting an example that other monks would follow. B. Culture in Spain and England: In Spain in the early seventh century St. Isidore of Seville (560-636 C.E.), wrote an encyclopedia called the Origins, covering many topics--mathematics, music, astronomy, medicine, religion, animals. In the early eighth century the Venerable Bede (673-735 C.E.), an English monk, wrote an excellent history of the Church in England, called the Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, as well as numerous scientific treatises. He was considered the most learned man in Europe in his day. However, these scholars were the exception. V. The Emergence of Western Christendom: Compared to the time of Pax Romana, the opening centuries of the Middle Ages seemed to be the "Dark Ages." Germanic, Christian, and Roman traditions were being woven together into a new civilization. At the heart of this new civilization was Christianity. The Germanic tribes had been pagans. As they moved into the Roman Empire during its declining years, however, they were converted to Christianity. In addition, Christian missionaries carried on the process of converting pagans after the fall of Rome. Thus, by 1000 C.E., most of Europe was Christian. From Italy to Ireland and from France to Poland, the Church in Rome headed by the Pope was the bond uniting the peoples of Europe. As learning died away during the Dark Ages, superstition and faith took its place. And since the era was a chaotic and frightening one, people took comfort in the only cultural anchor available to them--the Church. This was how the Catholic church became so strong in the Early Middle Ages. However, this period was also a formative time. VI. The Carolingian or Holy Roman Empire: Clear signs of the new civilization appeared in the Kingdom of the Franks, which stretched from France into Germany. In the last third of the eighth century Charlemagne (742-814 C.E.), the greatest of the Frankish kings, enlarged the size of his kingdom. He brought large parts of Western and Central Europe under his rule. On Christmas Day in the year 800, the Pope, head of the Roman Catholic Church, crowned Charlemagne "Emperor of the Romans," thus inaugurating the Holy Roman Empire. The Pope wanted support from this Germanic monarch for protection against his enemies. The ceremony was a sign that the Roman idea of a unified empire had not died. A. Different from Rome and Byzantium: Doubtless some believed that Charlemagne was reviving the Roman Empire. But Charlemagne's empire lacked Roman law and officials trained in administration, which the Byzantine Empire in the East had. Nor did it have great cities to serve as centers of trade and learning. B. The Nature of the Carolingian Empire: Instead of reviving the Roman Empire, Charlemagne's empire was the sign of something new. Its blend of Christian, Germanic, and Roman elements would come to characterize medieval civilization. Charlemagne's government grew out of Germanic customs. As a Christian ruler, Charlemagne was expected to defend Christianity and protect the Church against its enemies. The culture of his kingdom had its roots in the Greco-Roman past. C. The Carolingian Cultural Revival: Though Charlemagne was a warrior-king, he respected Greco-Roman learning. Hoping to improve the training of his clergy and officials, Charlemagne brought some of the finest scholars in Europe to his Palace School. There they collected books and read the works of ancient Roman authors. Their poems, histories, and religious works imitated the style of Roman literature. While they produced no great works of philosophy or science, these scholars revived interest in learning. The accomplishments of Charlemagne's empire were limited. However, they indicated that a common medieval civilization was emerging in Europe. It would take centuries for this civilization to reach its height. VII. New Migrations of Peoples, 850-1000. Charlemagne's empire did not survive his death in 814 CE. The kings who inherited the Frankish lands could not control powerful lords. Frequent invasions and raids further weakened their authority. The chief invaders were Norsemen from Scandinavia, once the homeland of the Germanic peoples. During the ninth century Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish raiders terrorized the coast of Europe and pushed inland along the rivers. Magyars from Central Asia also invaded Europe from their new pasturelands in the Pannonian Plain (the north-central Balkans: Austria, Hungary, and Yugoslavia. The original Pannonians were Illyrians). Mediterranean towns were attacked by Muslim invaders from North Africa and Spain. The invaders looted, burned, and massacred. Disorder spread over Europe. Gripped by fear, Europeans once again turned to powerful lords for protection. In response to this new migration of peoples, we have the development of the political-military system known as feudalism, which is supported by a socio-economic system known as manorialism.