* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Competing Explanations of Global Evils: Theodicy, Social Sciences

Symbolic interactionism wikipedia , lookup

Social contract wikipedia , lookup

History of social work wikipedia , lookup

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Development theory wikipedia , lookup

Political economy in anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Social Darwinism wikipedia , lookup

Development economics wikipedia , lookup

Sociocultural evolution wikipedia , lookup

Criminology wikipedia , lookup

Contemporary history wikipedia , lookup

Social group wikipedia , lookup

Structural functionalism wikipedia , lookup

Sociology of knowledge wikipedia , lookup

Philosophy of history wikipedia , lookup

Postdevelopment theory wikipedia , lookup

State (polity) wikipedia , lookup

Social history wikipedia , lookup

Social theory wikipedia , lookup

Sociological theory wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

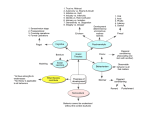

AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies AGLOS vol. 2 (2011): 27 – 45 ISSN 1884-8052 Copyright ©2011 Graduate School of Global Studies, Sophia University http://www.info.sophia.ac.jp/gsgs Competing Explanations of Global Evils: Theodicy, Social Sciences, and Conspiracy Theories By Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz Abstract: When global tragedies occur (pandemics, economic crisis, global warming, terrorism, etc), people will turn to three basic forms of explanations. Some will turn to their priest for a theodicy account of the event, others will turn to the sciences for a rational, secular account, natural sciences in the case of natural disasters, and in the case of humanmade evils, the social sciences. Yet others will turn to conspiracy theories to explain both natural and human evils—conspiracy theories that, like science, claim to be rational and secular. In short, religion, science and conspiracy theories are based on competing socially legitimate frames of global evils, they share common ground: conspiracy theory and science are both secular and appeal to reason and common sense knowledge, conversely conspiracy theories appeal to notions of “faith” and “belief” that pair them with forms of religious explanations. The strength of many conspiracy theories stem not from their “fringe” and anti-mainstream character, but from precisely those aspects of their narrative that appeal to established and legitimate forms of explanations of events. In short, conspiracy theories' narratives share a common secular rational frame with narratives put forth by social scientific narratives of those same events. This paper will describe how explanations based on different frames compete in order to become the legitimate narrators of global evil in society. Keywords: Global Evils, Theodicy, Social Theory, Social Sciences, Conspiracy Theories Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 27 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies Introduction Bad things happen and they happen on a global scale. The competencies to explain and deal with these evils (terror, global warming, epidemic outbreaks, world financial crisis, etc.) seem to transcend the power of individual nation states. When evil things happen in a globalized world, what are generally considered to be the socially legitimate explanations of these evil events? When global evil things happen, both natural and human made, people will turn to three basic forms of explanations. Some will turn to religion for a theodicy account of the event, or will turn to natural sciences in the case of natural disasters for a rational account, or to social sciences in the case of human made evils, also for a rational secular account. Yet others will turn to conspiracy theories, to explain both natural and human evils for accounts that, like science, claim to be rational and secular. A traditional religious narrative of an epidemic outbreak for example, might tell us that it is a natural evil that has come to happen as due punishment for our own human sins, making humans ultimately guilty for the epidemic. But science, for its part, will search for the rational, natural causes of the virus, map its genetic make up, decide potential risks for humans, devise possible cures and vaccine, etc., all without ascribing intent and ulterior responsibility of the event to any agent, human or divine (or better still, as bracketing the possibility of intent as just one of several working hypothesis). Other forms of explanations, conspiracy theories for example, will also use rational arguments for framing the same event but contrary to science, will ascribe human agency and intent to what otherwise would be consider a natural evil. For example, a human conspiratorial agent will be discovered as “responsible” for the creation and dissemination of the virus. The agent will ultimately, according to the conspiracy theory, benefit from the global evil thus unleashed. Conversely, where religious and conspiracy theory narratives both may ascribe global evils to volitional agents (but different agents, with different purposes, different methods, and for very different motives), science might see only natural events. For example in the case of the recent global financial crisis, a social scientist may explain the crisis as a natural event that follows predictable cycles of a reified “economic system”, even if explained in terms of innumerable human individual 28 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies decisions, the result is an event of a “natural” order that can be objectified and explained as a reality sui generis (Durkheim 1982). Conspiracy theories, on the contrary, will stress the “unnaturalness” of the crisis and will point to very concrete human agents that stand to benefit from it.1 Whereas social science may include motives of agents as only one variable of an explanatory equation, conspiracy theories will exalt those motives deterministically as central to their explanations. In doing so they will appeal to a rational secular frame and claim that social science explanations of the crisis are either naïve, themselves part of the conspiracy or indeed, not scientific enough and failing to appropriately use their own rational methods. This last form of argumentation can be clearly seen in the competing explanations of terrorist events as global evils. In a prominent example, the scientific explanations of the events of 9/11 are challenged by conspiracy theorists precisely for not being scientific and rational enough and for forgetting to apply common sense knowledge to the event.2 Conspiracy theories are devised that are very detailed in their use of scientific language: aeronautics, structural engineering, pyrotechnics, communication analysis, etc., and claim to be more scientific and rational than the mainstream scientific explanations of the event. Furthermore, conspiracy theories claim to make use of a superior form of common sense knowledge by following the principle of who benefits from producing the evil event. Thus, for example, common conspiracy theories of the 9/11 events explain them in terms of its use as a casus belli purposely created by the United States government in order to advance its imperialist interests. On the other hand, the distinction between natural and human evils is further blurred in terrorist events: they are obviously caused by human agents, but they strike with the undifferentiated cruelty of natural evils, killing both guilty and innocent. Global warming and its effects, and in general what has been called “global ecological catastrophes” (Beck 1999), are also narrated in very different ways. A traditional religious explanation finds no problem 1 For a conspiracy account of the recent financial crisis see for example the following short articles in selected conspiracy theory web pages: Richard C. Cook, “Is an International Financial Conspiracy driving World Events?” in http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid= 8450; Robert Chapman, “Global Financial Crisis: Real Estate Market Bubble” in http:// www.conspiracyplanet.com/channel.cfm?channelid=102&contentid=2367. Accessed August 15, 2010. 2 See for example http://www.911sharethetruth.com. Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 29 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies coupling human hubris with divine punishment as a form of explaining natural catastrophes such as earthquakes or storms. The agency of these catastrophes however, when traced to human intervention in the form of alterations to the ecosystem that may trigger them, becomes the object of conflicting forms of explanations between conspiracy theories and sciences. Again as in the previous cases, the narratives for these global evils devised by conspiracy theories are staged in the same frame as those produced by science, but diverging in notions of guilt, responsibility and intention. In short, religion, science and conspiracy theories are based on competing socially legitimate frames of narrations of global evils3, they share common grounds: conspiracy theory and science are both secular and appeal to reason and commonsense knowledge, conversely conspiracy theories appeal to notions of “faith” and “belief” that pair them with forms of religious explanations. The strength of many conspiracy theories stems, not from their “fringe” and counter main stream character, but from precisely those aspects of their narrative that appeal to established and legitimate forms of explanations of events. Conspiracy theories' narratives share a common secular rational frame with narratives put forth by social scientific narratives of those same events. It will be argued here that the perseverance of conspiracy theories challenge scientific discourses in their own field precisely because both share a common secular rational frame for explaining events. Three competing forms of explanations for Global Evils Theodicy We deal with the classic problem of explanation of evil in the world within the religious frame (theodicy4) when we face the attributes of the divine as incongruous with the reality of the world: as omniscient, God knows all evil; as omnibenevolent he wills all good, and as omnipotent he is capable of precluding all evil. Therefore: how is Evil possible in the world?5 Thus posed, the problem of evil is framed as a religious problem, 3 By socially legitimate narrative I refer to the notion of legitimacy put forth by social constructionists such as Berger and Luckman (1966). 4 Theodicy, or defenses of God in the sense introduced by Leibniz ([1710] 1990). 5 In Ricoeur’s succinct formulation: “God is all powerful; infinitely good; evil exists.” (1986, 26). The logical inconsistency of an all powerful and benevolent God with evil is first found in Epicurus. 30 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies and its solution falls within the disciplinary fields of theology and philosophy of religion. According to Weber, all world religions face the problem of theodicy but, “The more the development tends towards the conception of a transcendental unitary god who is universal, the more there arises the problem of how the extraordinary power of such a god can be reconciled with the imperfection of the world.” (Weber 1966, 138-39). The problem was therefore posed by Weber as one of increasing rationalization: an early and unintended consequence of inquiring for the causes of evil and not accepting them passively. Classically exemplified by Job’s experience in the Old Testament, a breach is made by which the incongruity of omnipotence with evil has to be rationally explained. As Morgan and Wilkinson comment, “The seeds of religious disenchantment thus appear to have been sown by religion itself, from which the rationalization of public realm emerged as a unintended consequence of a metaphysical commitment to a particular idea of the supramundane” (Morgan and Wilkinson 2001, 202). Gradually, as human agency came to the forefront with secularization, evil became a matter of individual morality. Consequently, the humanities were asked to answer the question of evil in the world. The theodicy question was secularized from its divine form (how is evil possible given a good God?), to a humanist version (how is evil possible given that humans are naturally good?). In this respect, the myths of the bon sauvage, humanized from the medieval theme of nostalgia of a lost paradise, where redeployed in order to assert the social corruption of the natural kindness of humanity (Eliade 1989). The incongruity between naturally good humans and social evils was explained by the corrupting effect of social institutions. Further rationalization later meant that human agency was understood to be pressured, or even determined, by social structures. The natural kindness of humans was further abstracted into the notion of Reason. Thus the social sciences came to assume the exalted position of holding the socially legitimate explanations of the causes of evil in the world. Various authors have described this as the process of displacing of the theodicy problem by its rationalized and secularized version, sometimes referred to as a “sociodicy”. 6 The name implies that the 6 It is unclear who coined the term “sociodicy”. The earliest reference I have come across is in Daniel Bell (1966). The term was also used by Vidich and Lyman in the introduction to their Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 31 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies narrations that were once the domain of discourse related to religion are now accounted for by the social sciences.7 Social Sciences What is important here is that although we witness a change in the basic cosmology for explaining the nature of evil in the social world, I consider that the mythical nature of this cosmology remains the same: stories on origins become rationalized, but they remain as basic myths on origins; explanations of evil change focus, but they remain theodicies (in their secularized form) in character; archetypal civilizing heroes become human, but remain as exemplary models for society, etc. In a society where the secular frame becomes the dominant one, these narrations become increasingly rational, more human and less divine, it is to be supposed that in this context the social sciences become accepted as in charge of the socially legitimate narration of social myths. Therefore, advancing further the argument made by Morgan and Wilkinson and by other contemporary authors, we can characterize the social sciences as the disciplines in charge of narrating, in normative form the, now secularized and rationalized, problematic of global evil. These narratives of the social sciences take the secularized form of descriptions history of American Sociology to describe how “In the early decades of the twentieth century, American sociology began to separate itself from its most visible religious orientations. Substituting sociodicy—a vindication of the ways of society to man—to the theodicy that had originally inspired them, American sociologists retained the original spirit of Protestant world Salvation. They substituted a language of science for the rhetoric of religion.” (1985, 1). It was also used by Bourdieu, for example, to characterize the neo-liberal explanation of suffering as necessary for progress. Bourdieu thus labeled neo-liberalism a “conservative sociodicy” (Bourdieu et al. 1993). In the 60s the term “anthropodicy” was proposed by Ernst Becker for a “secular theodicy” based on a Comtean inspired vision of a morally relevant unitarian “science of man” (Becker 1968). 7 Simon Locke has made a similar point in a recent article, further pointing to the parallel logical characters of conspiracy theories and modern social sciences as secular responses to suffering: Indeed [conspiracy theorizing] is an outcome of the same logic that produces the sciences of general social analysis, which show the same tendencies to interpret reality in terms of collective social processes often ultimately ascribed to the activities of one specific social group – hence “they” are to blame. Conspiracy culture, then, is as “normal” a condition of the modern world as are these sciences, a world in which the modes of mundane moral reasoning are shaped by a godless spirit that will nonetheless seek out a prospective pathway to salvation. God, supposedly, no longer offers a satisfactory path, while that to disenchanted nature is a hard road to travel. (2009, 582-3) 32 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies of unjust and irrational social arrangements against just and rational social possibilities; social phenomena, such as crime, inequality, poverty, vices, violence etc. (Bourdieu 1993), described as social problems (Stivers 1991), and particularly the survival of the enlightened humanist narrative of the bon sauvage in its rationalized expression of the exploited poor, the marginalized, the proletariat, the third world revolutionary or the immigrant worker to the first world, and still in its original form as the pre-modern, “natural”, indigenous in remote areas of the world. Furthermore, contemporary society is characterized as dealing with evil in terms of managing risks, in many instances they are produced as unintended consequences of modernity itself (Giddens 1990; Beck 1992). Finally, society itself becomes the causal locus of evil for social sciences in, for example, narrations of the repression of society upon the individual (Marcuse 1966), or of totalitarian societies (Arendt 1971). In its structure of narration of evils the modern rationalization retains the paradox of theodicy: how is evil possible? In classical sociological theory it is characterized as a type of hubris, as a price humans pay or as an “unintended consequence” of modernity that still resonates in contemporary sociology.8 As a further step in the process of rationalization of the explanations of evil, the social sciences, historically tied to the emergence of the nation state, acquire a post-national character, and aspire both to become global and to explain social phenomena beyond the boundaries of national settings. Thus, we witness the emergence of disciplines of global social sciences that deal with the explanation of these events. Social sciences prefixed by “global” would ascribe to the guiding myths of national social sciences but in terms of progress and a better (global) society. They would 8 such as for example as described by Ulrich Beck: The approach to knowledge in reflexive modernization can be summarized, greatly oversimplified, as follows: 1. The more modern society becomes, the more knowledge it creates about its foundation, structures, dynamics and conflicts. 2. The more knowledge it has available about itself and the more it applies this, the more emphatically a traditionally defined constellation of action within structures is broken up and replaced by a knowledge-dependent, scientifically mediated global reconstruction and restructuring of social structures and institutions. 3. Knowledge forces decisions and opens up contexts for action. Individuals are released from structures, and they must redefine their context of action under conditions of constructed insecurity in forms and strategies of “reflected” modernization. (Beck 1999, 110) Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 33 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies depart from the nation state centered social sciences in their explanations of national or local evil, with the emergence of “globalization” as a structural process that is understood as either the cause of evil (as a neoliberal homogenizing ideology), or as the next step in a rationalizing world trend whose preclusion would be the origin of evil. More or less optimistic conceptions of globalization and pessimistic anti-globalization can be thus placed in a continuum of interpretation, with a few social scientists denying forthright the existence of the phenomenon of globalization per se (Rosenberg 2005), but most disagreeing mainly in its positive or negative effects for the social.9 Conspiracy Theories However, as argued here, the social sciences do not hold the contemporary monopoly of being the legitimate social narrators of global evils. Several students have pointed out that conspiracy explanations of social events have increased in popularity in recent years (Parish and Parker 2001). The bestseller status of literary fictions and films that deal with conspiracies are presented as confirmations of this fact. The Internet is often mentioned as an especially adequate vehicle for the transmission of these theories.10 Much of the early sociological literature on the subject, such as Georg Simmel, dealt not with conspiracy theories, but with conspiracies themselves. 11 The emphasis was in the sociological analysis of the secretive aspects and internal functioning of conspiracy cabals and secret groups. Later literature has acknowledged that there is little point in denying the fact that people conspire, that is, they participate in political 9 According to David Held and Anthony McGrew the globalization/anti globalization divide is mainly normative in character: “Since all explanatory theories if globalization are implicitly, if not explicitly, normative, disagreement about its essential nature is, in part at least, often rooted in different ethical outlooks. Indeed the most contentious aspect of the study of contemporary globalization concerns the ethical and the political: whether it hinders or assists the pursuit of a better world and whether that better world should be defined by cosmopolitan or communitarian principles, or both.” (Held and McGrew 2007, 173). 10 For recent counts of Conspiracy Theories see: Patán (2006). A serious compilation, despite its popular format presentation, with excellent biographical and Internet sources is McConnachie and Tudge (2005). Older, dated but still useful accounts are Anton Wilson (1998) and Vankin and Whalen (1999). 11 The classical sociological study of conspiracies and conspiracy groups (not of conspiracy theories) is the chapter on “The Secret Society” in Simmel’s Sociology (1950). 34 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies actions in which they “breath the same air” of a plot. In a certain sense, as most authors reviewed in the following pages admit, conspiracies are part of social life: they are everywhere.12 Furthermore, in everyday life, every time we meet with a person because we want to reach a certain goal, and we think that the other person may either share that goal or help us achieve it, but we exclude a third person from our meeting because we consider this third person could jeopardize the plan, we are conspiring. Everyday experiences are full of such events, and they do not necessarily entail negative connotations. The consequences of a conspiracy can be positive (arguably, most conspirators are convinced of the positive consequences of their actions); we can conspire to surprise a friend with a party, for purposes of beneficence and charity, or to further a political position we consider correct. We might also conspire to commit an unlawful or evil act, and much legislation contemplates provisions against conspiracies to commit crimes. Serious crimes are usually described as acts of mental and moral weakness, as the products of elaborate plots, or both. Much of the police story literary genre relies on the latter type of description; There is a crime, usually in a set location, and there is a detective who follows the signs left by the perpetrator, in the forms of clues, that lead him to unravel the plot, and thus, to the criminal. The criminal is a conspirator, although in many cases he may act alone and not co-nspire with anyone. In both cases, the relatively benign party organizers of the previous paragraph in one extreme, and the criminal on the other, represent micro and common forms of conspiracy: a limited plot for a limited end. Once the end is achieved, the conspiracy stops, although in the case of the criminal a further, greater plot may develop in order to cover up his crime. However, social life may present us with far greater instances of conspiracies: groups that try to impose their objectives through obscure and hidden mechanisms. They are portrayed in popular imagination and in literary fiction as meeting in shadowy places, away from the public light and, through procedures that are fundamentally undemocratic and secret, deciding upon the destiny of other people and imposing great evil 12 As Hofstadter, one of the most often quoted authors on the matter, pointed out: “One may object that there are conspiratorial acts in history, and there is nothing paranoid about taking note of them. This is true. All political behavior requires strategy, and anything that is secret may be described, often with but little exaggeration, as conspiratorial.” (Hofstadter 1965, 29). Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 35 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies upon society. Sometimes they represent unimportant and irrelevant groups that can only reach their objectives through an infinite chain of plots over plots. But more often they are groups with almost supernatural powers over infinite human and material resources. We are thus faced with the assumption that conspiracies are everpresent in social life and that they are behind much of the evil that afflicts society, but that there are many levels of conspiracies that follow a continuum, from limited and relatively innocuous plots, with reduced objectives and consequences, to world domination conspiracies.13 The term “conspiracy theories” will be used here to define explanations of global evils that tend to the latter end of the continuum. The most often cited analysis of these types of conspiracy theories is Karl Popper’s. His main argument will be briefly recounted here. In The Open Society and its Enemies, Popper describes a theory which is widely held but which assumes what I consider the very opposite of the true aim of the social science; I call it the ‘conspiracy theory of society’. It is the view that an explanation of a social phenomenon consists in the discovery of the men or groups who are interested in the occurrence of this phenomenon (sometimes it is a hidden interest which has first to be revealed), and who have planned and conspired to bring it about. (Popper 1995, 324) For Popper, conspiracy theories are simply wrong interpretations of reality, often used in social sciences they are however, contrary to scientific aims. Conspiracy theories derive from Historicism, putting causes of social phenomena beyond the human realm; they are the consequences of a secularization of the religious belief that gods play with social life. The result of these types of explanations is that people cease to be agents of their own history, and instead become pawns of either other people or abstract structures. As mentioned above, there is the common assertion that even as “overarching conspiracy theories are wrong [this] does not mean they are not on to something” (Fenster 1999, 67), but also that by using the term “conspiracy theory” as a disqualifying argument we may be actually 13 Räikkä (2009, 186) distinguishes between non-public conspiracy from public conspiracy theories. Kelley (2003, 106) refers to “truly vast” conspiracy theories for the latter part of the continuum. 36 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies playing into the hands of “manufactures of consent” (the real agents of evil) that preclude certain forms of criticism. Thus Mark Fenster argues for example, in the introduction to his book, that in “political discussions with friends and opponents, one can hurl no greater insult than to describe another’s position as the product of a ‘conspiracy theory’.” (Fenster 1999, xi). To be sure, as has been argued by Bell and Bennion-Nixon (2001), much academic critical discourse has more than just a ring of conspiracy theory to it, but many academics feel their work is unfairly labeled.14 Here it is important to note that, in fact, many critiques of society, from the left and the right, rely heavily on the notion that hidden groups or abstract structures, beyond the actor’s control, are behind most evils. The purpose of these types of critiques is to “reveal” hidden truths through the study of discourse as expressions of meaning hidden between lines, and/or the institutional analysis of how structures of decisionmaking are penetrated by more or less hidden interest groups. These critiques can be academically sophisticated, and furthermore, they may be right in many of their assertions or not. However, the fact that they search for abstract explanations of social reality does not turn them into conspiracy theories in themselves, although they may be used in politically simplified versions, as the basis for many conspiracy theories. We are here faced with cases in which science and conspiracy theories, because they claim the same rational secular frame, produce similar narratives of social evils. Furthermore, an infinite spiral of mutual accusations of conspiracy theorizing is often presented, in the literature on the subject, as a result of certain political uses of conspiracy theories. In another section of the paper quoted above, Pigden presents this problem as an inappropriate use of Occam’s razor: for Pigden, the simplest explanation is not always the best, as he implies, is argued by Popper, particularly when we deal with social phenomena. The common political use of conspiracy theory these authors are arguing against is typically seen when a political actor dismisses as a conspiracy theory, for example, accusations of acting according to vested interests. The political actor may appeal to a simpler explanation of the facts versus a convoluted and complex conspiracy 14 A good example of this preoccupation is a comment in a critique of Popper by Charles Pigden (1995): “Like many on the left, I think Popper’s critique of conspiracy theories has provided rightwing conspirators (and, in some cases, their agents) with an intellectually respectable smokescreen behind which they can conceal their conspiratorial machinations.” Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 37 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies theory explanation of the same facts. This is quite different from the political actor claiming a conspiracy behind the accusations, and therefore appealing to a “more complicated” explanation of the facts. In both cases there is a notion of “degrees of complexity” of knowledge constructions as reflections of a “simple” or “complex” social phenomenon. These notions of complexity are the results of conceptions of how institutions work, especially with respect to the decision-making processes and the internal functioning of these institutions. A close reading of Popper reveals that he understood conspiracy theories not as knowledge constructions that reflect notions of a complex social reality, but in fact as a reflection of a simplistic conception of institutional functioning. Conspiracy theories are knowledge constructions that claim a simple social reality of cause and effect guided by a complex plot, which is something very different from claiming that social reality is complex. Conspiracy theories pretend to reveal a simple reality made complex by conspirators, and politically they often long for a utopian political world in which nothing will be concealed; the perfect open political system in which everything is transparent, a world of perfect sincerity as well as perfect correspondence between good motives and their always positive consequences. In their most extreme cases, conspiracy theories long for an a-political utopia because political responsibility and sincerity is for them, and oxymoron. Furthermore, Popper clearly argued, as insisted here, that he was not negating the existence of conspiracies in society. He did argue, however, that conspiracies very rarely achieve their stated ends. But, some critics could rightly retort that some conspiracies do achieve their ends, and the discussion could be collapsed into comparing successful and unsuccessful conspiracies, which was not Popper’s intention. The important point is to stress that social action has unintended consequences and that conspiracy theorists have a hard time dealing with the notion of unintended consequences of actions. In short, according to Popper, for the conspiracy theorist, if a consequence can be traced through a plot, to motives of the actors, then there is no room for the unexpected. Conversely, social reality becomes a mere symptom of an intentional plot that needs to be read. This simple explanation may work well for small limited conspiracies, but Popper would argue that it does not constitute a viable way for explaining broader social phenomena. In this line, Dieter Groh, for example, has argued that conspiracy theorists underestimate “the complexity and 38 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies dynamics of historical processes” and points that they “ascribe in a linear manner the results of actions to certain intentions” (Groh 1987, 11). The conspiracy theorist can describe the discovery of this code as a moment of illumination. It allows him to follow back the sequence of events, from the everyday facts that would otherwise remain random and unexplained to the motives of the conspirator. As in classical police fiction, once the motives for the crime have been revealed, the crime is half solved. He who had motives to commit a murder, is the murderer. It is only left for the detective to reconstruct the logical sequence of events that lead from the crime to the criminal. Explanations based on this type of logic do not pose a complex social and political reality; on the contrary they greatly simplify reality as the product of intentionally driven, monocausal linear events. Therefore, given the complexity of social reality and global events as well as the unintended consequences of social action, it was not Popper’s intention to counter conspiracy theories of how society works with a “theory of the innocence” of political actors. Again, it is important to state that a study of conspiracy theories should not hold that society is devoid of actors with diverse and often conflicting interests who act in order to advance those interests.15 However, even if conspiracies exist and are part of social life, and even when conspiracy theories and social sciences are couched on the same secular rational frame, differences persist between a conspiracy theory approach and a scientific approach to the explanation of global evils. More precisely, despite the superficial similarities between the rational and secular appeals made both by social sciences and conspiracy theories—similarities that make conspiracy theories a powerful alternative to social scientific explanations of global 15 Räikkä provides several famous examples of events that were once dismissed as conspiracy theories: In 1941 a belief in the Holocaust was a belief in some sort of conspiracy theory, as it denied the official claim that the Jews were merely being resettled. But now, Holocaust denial is a crime in some countries, for instance in the UK, and the belief in the Holocaust is certainly not called a conspiracy theory. The theory that revealed that President Nixon was indirectly involved in the Watergate burglary was also once a conspiracy theory, but now it is part of the official explanation of the White House tragedy in 1972. People who claimed that President Reagan sold guns to Iran in order to fund right-wing Contra guerrillas in Nicaragua were conspiracy theorists in 1986, but people who make the same claim now are just repeating something that everybody knows.” (2009, 187) To these it is illustrative to add the Dreyfus affair as an example of a vast conspiracy that was successful for some time, until the conspiracy theorists Dreyfusards were finally able to reveal its existence (Johnson 1966). Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 39 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies evils, there are also important divergences as to how claims to rationality and common sense are made by the two competing narratives. The social scientist, according to Popper, holds that society and therefore political action, is the outcome of a complex and multivariate web of relations and not the sole outcome of a purposeful mono-causal chain of events. Especially when dealing with political action, the social scientist knows of unexpected consequences of such actions and is willing to include such consequences in his explanations. Therefore, he may accept the existence of conspiracies as part of the explanation of certain events, but deals with them as only one of many variables determining those events. Furthermore, social scientists present (or at least attempt to present) their theories as falsifiable. That is, their theories are subject to replication and therefore may be proven wrong by other scientists. The fact that they may be wrong is not taken as further proof of a totalistic attempt to hide the truth by the conspirators. Granted, this is a very optimistic assessment of social sciences, but it is one that most would recognize as their methodological utopian goal. Contemporary conspiracy theories are, like social sciences narrations of events within the secular rational frame but, contrary to social sciences, they state that every single event in social life can be explained as the product of an obscure political machination by certain groups of actors. They do not deny the complexity of social life, but for them, that complexity is possible only inside the linear conspiracy plot that can, in effect, become extraordinarily complicated in its effects. As Umberto Eco (1992) has stated, conspiracy theorists fall victims to their own over-interpretative plots and create self-sustainable complexities that lead to new interpretation in an infinite irresolvable chain. This “complexity” is what makes for the thrilling character of most conspiracy fiction. But, as in fiction, this complexity is rather illusory and becomes a very simple sequence of interconnected events once the conspiracy code has been unveiled. Conclusions The following table summarizes the argument made in the previous paragraphs. Read from left to right the graph represents the modernization argument of a progressive rationalization in terms of the transit from a dominant religious frame for narrating evils to a secular frame. In the 40 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies boxes are the dominant cosmogonies (in cursive), the prevailing explanations of evils, and in bold, disciplines of knowledge. Religious Frame Secular Frame Myth of Origin / Explanatio ns of Evil Lost Paradise. Fall from Divine Grace. Demon as corruptor. Redemption as return to God/Paradise. The bon savage. Humans as naturally good. Fall from the state of nature. Society as corruptor. Redemption as return to nature. The downtrodden of the world. No fall, but in its place myth of progress to more rational arrangements in society. Place of corruptor assumed by irrational obstacles to this progress. Redemption by rational overcoming of these obstacles. The downtrodden of the world. No fall, progress as globalization. Globalization as evil or good, depending on standpoint. Redemption by globalizing or by resisting globalization. Legitimate narrator of evil. Theodicy. Religion. Theodicy. Humanities. Sociodicy. Social Sciences. Sociodicy. Conspiracy theories. “Global” social sciences. As can be seen in the last box closest to the secular frame, the argument presented here challenges traditional accounts of modernization as the triumph of rational secular forms of explanation. Even as it acknowledges that triumph, it contends that science is not the only socially legitimate narrative within that frame. I argue here that the secular rational frame allows for more narratives than modern science. The narrative presented here fits into the world society argument made by Meyer and his colleagues. Meyer has explained in his work that globalization includes several dimensions; apart from the increasing political, military and economic interdependence between sovereign nation states, this also means the “expanded interdependence of expressive culture through intensified global communication” and “the expanded flow of instrumental culture around the world” (Meyer 2002, 233). This increase and expansion of interdependence has an impact on the legitimacy we ascribe to the myths that explain society and its evils. Thus, even if world society “is stateless and lacks much of a collective actor [it] contains much cultural and associational material that defines itself as made up principally of very strong and highly legitimated actors. These arise from a rationalized (scientific) analysis of nature as universal and lawful and thus suited to rational and purposive action” (Meyer 2002, 237). Furthermore he adds that actors: arise even more from a secularized analysis of a universal and lawful moral or spiritual authority: the high god no longer acts in history but Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 41 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies sacralized human actors do, carrying legitimated agency for their own actions under valid and universal collective principles. (Meyer 2002, 237) These actors described by Meyer have organizational expression not only in modern institutions, but also in culture and in social scientific theories that describe their life, their sufferings and their evils, within the secular rational frame. The secular rational frame (both as scientific and conspiracy theories narratives), contrary to the religious frame, which has a collective character, is centered on the individual actor. According to Meyer, individual actors become in modern society almost “little gods”; rights, policies and agency are legitimated as ascriptions to individual actors and not groups. Globalization, as increasing interdependence and convergence of institutions is part of the long secularizing process that stresses this condition of a world of individuals that act as such and not as members of collectives. The dominant frame for explaining evil in a globalizing world is secular, rational and individualistic. Its main rhetoric expression is the discourse of science. Through a process described by Meyer, especially in the realm of education, globalization has meant the increasing legitimacy of science as the accepted explanation for events. However, as is argued here, science is but one discursive expression of a broader rational secular frame, but it is not the only discursive expression of that frame: conspiracy theories also claim to be legitimately considered as rational secular arguments for the explanation of evils. Furthermore they claim an agency that sometimes runs contrary to the dominant individualistic agency. Most conspiracy theories ascribe a collective agency to those responsible for the evils of the world, but at the same time vindicate the figure of the lonely individual researcher who works alone in revealing those evils and their perpetrators. Modern globalized society has a way of explaining evil events that reflects its cosmogonic narrative. Explanations that appeal to reason, individualistic values, and responsible agents have more social legitimacy than those that appeal to divine will. The legitimacy warranted by these cosmogonic values does not necessarily mean that scientific explanations of events are readily accepted as legitimate explanations for these events. Conspiracy theory narratives often compete with science and they are often successful in claiming to be the real representatives of the rational frame of explanation. 42 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies References Arendt, Hannah. 1971. The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Meridian Books. Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk society: Towards a new modernity. London: Sage. ———. 1999. World risk society. Cambridge: Polity Press. Becker, Ernst. 1968. The structure of evil. An essay on the unification of the science of man. New York and London: The Free Press. Bell, Daniel. 1966. Sociodicy: A guide to modern usage. The American Scholar 35: 702-05. Bell, David, and Lee-Jane Bennion-Nixon. 2001. The popular culture of conspiracy/the conspiracy of popular culture. In The age of anxiety: Conspiracy theory and the human sciences, edited by Jane Parish and Martin Parker, 133-52. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers/The Sociological Review. Berger, Peter and Thomas Luckman. 1966. The social construction of reality. A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. Bourdieu, Pierre, et al. 1993. La misère du monde. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The rules of sociological method and selected texts on sociology and its method. Ed. Steven Lukes. New York: The Free Press. Eco, Umberto. 1992. Interpretation and overinterpretation. Edited by Stefan Collini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Eliade, Mircea. (1955) 1989. Le Mythe du Bon Sauvage. In Mythes rêves et mystères. Paris: Gallimard. Fenster, Mark. 1999. Conspiracy theories: Secrecy and power in the American culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Giddens, Anthony. 1990. Consequences of modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. Groh, Dieter. 1987. The temptation of conspiracy theory, or: why do bad things happen to good people? Part I: Preliminary draft of a theory of conspiracy theories. In Changing conceptions of conspiracy, edited by Carl F. Graumann and Serge Moscovici. New York: Springer-Verlag. Held, David, and Anthony McGrew. 2007. Globalization/anti-globalization. Beyond the great divide. Cambridge UK and Malden MA, Polity Press. Hofstadter, Richard. 1965. The paranoid style in American politics and other essays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Johnson, Douglas. 1966. France and the Dreyfus Affair. London: Blandford Press. Keeley, Brian L. 2003. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition! More thoughts on conspiracy theories. Journal of Social Philosophy 34:104-10. Liebniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. (1710) 1990. Theodicy. Edited by Austin Farrer, and translated by E. M. Huggard. Chicago: Open Court. Locke, Simon 2009. Conspiracy cultures, blame cultures, and rationalization. The Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 43 AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies Sociological Review 57(4): 568-85. Marcuse, Herbert. 1966. One-dimensional man: Studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. New York: Harcourt Brace and World Inc. McConnachie, James, and Robin Tudge. 2005. The rough guide to conspiracy theories. London: The Rough Guides. Meyer, John W. 2002. Globalization: Sources and effects on national states and societies. International Sociology 15(2): 233-48 Morgan, David, and Iain Wilkinson. 2001. The problem of suffering and the sociological task of theodicy. European Journal of Social Theory 4(2):199-214. Parish, Jane, and Martin Parker, eds. 2001. The age of anxiety. Conspiracy theory and the human sciences. Oxford: Blackwell. Patán, Julio. 2006. Conspiraciones: Breve historia de la conquista del mundo por los extraterrestres, los masones, la ONU, las elites financieras, el establishment, etc. Barcelona: Cromos Paidos. Pidgen, Charles. 1995. Popper revisited, or what is wrong with conspiracy theories? Philosophy of the Social Sciences 25(1):3-34. Räikkä, Juha. 2009. On political conspiracy theories. The Journal of Political Philosophy 17(2):185-201. Ricoeur, Paul. 1986. Le mal: Un défi à la philosophie et à la théologie. Ginebra: Labor et Fides. Weber, Max. 1966. The sociology of religion. London: Methuen. Rosenberg, Justin. 2005. Globalization theory: A post-mortem. International Politics 42(2):2-74. Simmel, Georg. 1950. The sociology of Georg Simmel. Translated, edited and with an introduction by Kart H. Wolf. New York: The Free Press. Stivers, Richard. 1991. The concealed rhetoric of sociology: social problem as a symbol of evil. Studies in Symbolic Interaction 12:279-99. Vankin, Jonathan, and John Whalen. 1999. The 70 greatest conspiracies of all time. New York: Citadel Press. Vidich, Arthur J., and Stanford M. Lyman. 1985. American sociology: Worldly rejections of religion and their directions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Wilson, Robert Anton. 1998. Everything is under control: Conspiracies, cults, and cover-ups. New York: Harper Perennial. 44 Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz AGLOS: Journal of Area-Based Global Studies ————— Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz is a Ph.D. student in the Graduate Program in Global Studies at Sophia University, Japan. He holds an M.A. degree in global studies from the same program and an M.A. in sociology from the University of Miami. He is a sociologist (licenciado en Sociología) form the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Caracas, Venezuela, and currently teaches social theory at the Universidad Central de Venezuela and media theories at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. Hugo Antonio Pérez Hernáiz 45