* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Individual, dyadic and network effects in friendship

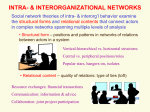

Actor–network theory wikipedia , lookup

History of the social sciences wikipedia , lookup

Network society wikipedia , lookup

Six degrees of separation wikipedia , lookup

Peer-to-peer wikipedia , lookup

Tribe (Internet) wikipedia , lookup

Social network wikipedia , lookup

Gender roles in childhood wikipedia , lookup

GENUS, LXVII (No. 3), 1-27 GIULIA RIVELLINI* – LAURA TERZERA** – VIVIANA AMATI*** Individual, dyadic and network effects in friendship relationships among Italian and foreign schoolmates 1. INTRODUCTION The foreign presence in Italy is by now a well-consolidated and continuously growing phenomenon. Between 1990 and 2008, this presence - both legal and illegal - has more than tripled. According to estimates, in 1990 there were 1,144,000 foreigners; in 2008, 4.3 million (Fondazione ISMU, 2010). More than 95% of them come from countries with high emigration levels (CHEL1). The presence of foreigners was and still is not uniform throughout the country. The destination of most migration flows, either directly or as a result of mobility once in the country, is northern Italy. On January 1st, 2010 as many as 61.6% of foreigners were living in the North, one quarter in central Italy and only 13.1% in the South (Istat, 2010). In addition, migration in Italy is usually definitive, as evidenced by an increasing presence of families and minors (Terzera, 2010). The latter, for example, accounted for less than 3% of total resident minors in 2003 and increased to 9.1% in 20092. Minors who joined their parents already living in Italy increased from nearly 3,000 in the early 1980s to 40,000 in 2006. Another example of the transformation of the migrant contingent into a population is the growing number of children born of at least one foreign parent: if “only” 6,000 children were born to foreign parents in 1992, this number has risen to more than 77,000 in 2009, accounting for 13.6% of total newborns in Italy. The growing presence of foreign minors, especially from 2000 onwards, can also be attested to by the increase in foreign pupils attending Italian public schools (Figure 1). The process of settlement is a fairly recent event in Italy, since the heaviest immigration flows have occurred in the past 20 years. Therefore the immi*Dipartimento di Scienze Statistiche, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano, Italy. ** Dipartimento di Statistica, Università Milano Bicocca, Milano, Italy. *** Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany. Corresponding author: Giulia Rivellini; e-mail: [email protected]. 1 This definition includes countries which are part of the special aggregate “LDR, Less Developed Regions” used by the UN, as well as East Europe, which is considered part of the MDR – More Developed Regions (http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Excel-Data/definition-of-regions.htm). 2 All the data presented in this section are official and provided by the National Institute for Statistics (www.demo.istat.it) or by the Minister of Research and Education (www.miur.it). 1 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI grants’ children3 are the first generation of foreign people, who are partially or totally growing in Italy. Because of this situation, in Italy at present there is a near-concurrence between immigrants’ children and minors. Thus we have the opportunity to study migrant children at ages which are critical for the formation of their personalities. Figure 1 – Pupils with non-Italian citizenship. 2001/02-2008/09 Source: Miur, several years. Studying immigrants’ children is important, above all, to understanding the level of integration of the immigrant population. The experience of those countries with a long history of migratory inflows suggests that, in fact, integration is possible in the first generation but more likely in the second and in the later generations (Crul et al., 2003; Farina et al., 2007; Thomson et al., 2007). Several aspects can be taken into account to measure or give an indication of the integration level of the descendants of the immigrants. These include the construction of identity (affected by regulation regarding citizenship), employment and training opportunities, culture, lifestyle, social settings and relationships. This paper has been developed based on the awareness that among all the factors useful for empirically describing the integration process, the analysis of peer networks reveals a perspective that has not yet been widely explored in Italy and is full of interesting implications (Rivellini, 2007; Gilardoni, 2008; Casacchia et al., 2009; Amati, 2009). One of the settings where friendship relationships among teenagers develop is undoubtedly the school (compulsory in Italy until the age of 16) which 3 This group includes second generations (i.e. children born in Italy of foreign parents) as well as the so-called generations 1.25, 1.5 e 1.75 (see Rumbaut, 1994), that is to say those who arrived in Italy before coming of age, when they were younger than 18. 2 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS can also facilitate meeting of classmates outside school. In this age group, the preferred friends are those with whom you can chat, start going out and confide the first secrets. On the other hand, the communication difficulties (not only in terms of language) which limit the exchange and the possibility of meaningful relationships with classmates may sometimes cause discrimination and exclusion (Caneva, 2011). This might lead pupils to become even more introverted. Therefore, if we consider the school as a training ground for social relationships, exploring friendships outside of the school setting may provide further insights as to children’s social integration level. Our hypothesis is that the first generation of immigrants’ children finds it more difficult to fit in because of a discriminatory attitude, generated in most cases by migration being a relatively novel phenomenon in Italy. However, as suggested by the literature, individual factors (i.e. migration history) and/or structural factors, associated with the peer network within the classroom, may either alleviate or worsen such difficulties. For instance, relational data revealed the existence of discrimination between black and white students in the USA and the important role of school classes in the integration process (Hallinan et al., 1987; Moody, 2001). In the Netherlands, several studies investigated the existence of ethnic boundaries between Dutch children and their classmates of ethnic minorities (Lubbers, 2003; Baerveldt et al., 2004; Baerveldt et al., 2007; Lubbers et al., 2007; Vermeij, 2009) in friendship networks. The opportunity theory4 considers school classes as the privileged place where both foreign-born5 and Italian pupils get in touch, and foster inter-ethnic relationships. Using the above-mentioned approaches and theories, in this paper we want to study friendship networks and thereby highlight the state of segregation and marginalization of immigrant´s children in Italy. The following individual characteristics are considered essential in order to understand processes associated with the migratory phenomenon: gender, as suggested by psychological literature (Confalonieri et al., 2005; Petter, 2007), the area of origin and socialization6. 4 The opportunity theory states that contacts within people of different ethnicity can reduced prejudices, increasing the chance of inter-ethnic relationships (Hallinan, 1982). 5 The origin of immigrants’ children is defined here as a function of the parents’ birthplace, because in Italy the principle of ius sanguinis is applied as regards acquiring citizenship. For more details, see Casacchia et al. 2008. 6 In this area of study, by socialisation we mean the process whereby information regarding the cultural heritage of a community is passed on and internalized. For the analysis conducted here, a distinction is made between individuals with complete Italian socialization (born in Italy or who came here before starting school); partial Italian socialization (those who attended school both abroad and for at least four years in Italy) and socialized “elsewhere” (i.e. arrived in Italy within three years before the survey date). 3 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI If, on the one hand, marginalisation is considered the absence of relationships with others, and segregation the prevalence of intra-ethnic relationships, then social integration is defined here as the outcome of a behaviour which places inter-ethnic relationships above intra-ethnic relationships. Thus, from an analytical perspective, our hypothesis states that it is more likely to observe a friendship relationship between pupils of foreign origin than between an Italian and an immigrants’ child. To verify this hypothesis, we jointly analyse the structural properties of friendship networks of lower secondary school classmates and their individual and migratory characteristics. Data used were collected in 2006 in Lombardy - a region in the NorthWest of Italy - by Fondazione ISMU7 as part of the national project “ITAGEN2” . This region is interesting because: a) it is the region with the largest population of foreigners (between one-fifth and one-quarter of the total population of foreigners); b) it is one of the regions in Italy where migration is more consolidated (for example, with a large presence of immigrant families). The focus on Lombardy can be illustrative for phenomena which will presumably spread to the rest of Italy later on. The paper is organized as follows: section 2 describes the data and methodology, focusing on the choice of statistical network model; sections 3 and 4 present the descriptive evidence and estimates of the model parameters. The last section contains some concluding remarks on new elements emerging in regard of the topic and the methodology that was used. 2. DATA AND METHODS 2.1 Survey sample and friendship measurement To learn more about immigrants’ children in Italy, a nationwide sample survey was conducted in 2006 (ITAGEN2) - promoted by eight universities with the support of local public and private agencies or foundations - on a subgroup of minors (Italian and foreign) in lower secondary school (Casacchia et al., 2008). The choice of that target population was underpinned by two main factors: these kids (pre-adolescent) are old enough (>11 years) to be able to autonomously fill in a structured questionnaire requiring about one hour of their time; and the chosen grade of the school is compulsory and precedes the choice of whether to go on to senior high school. This transition point is important because already today there is evidence of significant differences between Italian kids (many of whom choose to go on to senior high school) and foreignborn kids (who more typically choose a professional training school). The survey sample of Lombardy consists of 17,277 pupils, both Italian and children with at least one foreign parent (for more details of the national 7 ISMU, Iniziative e Studi sulla Multietnicità, www.ismu.org. 4 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS sample structure see Dalla Zuanna, 2008). In this paper we consider only pupils attending seventh and eighth grade (11,245 cases), because it is assumed that friendships among classmates are consolidated by then. The questionnaire of the national survey was divided into 7 sections, and included questions about the demographic and social characteristics of the pupils and their relatives, as well as the future expectations and the free time of the children. An additional part related to the collection of network variables (see below for a detailed description) was added to the questionnaires handed out in Lombardy and Lazio. The information concerning kids´ free time allow us to analyse the existence and strength of the friendships of immigrant´s children (with Italians and/or foreigners) outside school, and compute an indicator of the ‘friendship strategy’ (Berry, 2001). The indicator is a combination of the answers to the following four questions: do you have Italian friends? Do you have non-Italian friends? Do you see your Italian friends outside school? Do you see your foreign friends outside school? Those who say that they have and see both Italian and foreign friends are defined as “integrated”, those who see only Italian friends are considered “assimilated”; if the friends they have and see are mainly foreigners they are “segregated” and, finally, those who have neither Italian nor foreign friends are classified as “marginalized”8. This preliminary part refers to questions which do not precisely define the type of tie (e.g. by defining it as a parental bond or one deriving from being part of the same sports team or association, or chosen friendships), nor allow us to identify the persons as friends, thus preventing a measurement of the reciprocity, homophily and balance effect in the relationships. For the sake of clarity, let us consider Figure 2. Reciprocity (Wasserman et al., 1994; Baerveldt et al., 2004; Scott, 2007) involves pairs of actors and represents the tendency that both the ties from Ego to Alter and from Alter to Ego are present (Figure 2a9). In terms of friendship, reciprocity suggests that two actors named each other as a friend. Homophily can be described using the adage “birds of a feather flock together” and it has been studied across a wide range of settings, attributes and relationships (Shrum et al., 1988, McPherson et al., 2001). More specifically, homophily states that actors prefer to be related to others who show similar characteristics. Looking at Figure 2b, this means that ties between Ego and Alter which are similar with respect to a certain attribute (indicated by the same colour of the node) are more probable than those between actors who differ with respect to it. For instance, many friendship studies proved that ties between people of the same gender and race are more probable than those between people of different gender or race. Finally, when two or more actors show the same pattern of relationships (Figure 2c), that is 8 9 For more details regarding how the indicator was constructed, see Paterno et al., 2008. For Figure 2, 3, 4 and 5 see Brandes et al., 2004 and the webpage http://visone.info/. 5 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI considered to be balance (Cartwright et al., 1956; Wasserman et al., 1994). In terms of friendship, this suggests that Ego and Alter agree in their friendship choices since they choose the same people as friends. Figure 2 – Reciprocity, homophily and balance effects. To disentangle these effects and to investigate the ties connecting the members of a group or system, a closed network approach is necessary. In our context, the close network is defined by the classmates and the friendship relationships existing among them. To collect the relational data, part of the questionnaire in Lombardy was dedicated to measuring the complete emotional and instrumental network (McCallister et al., 1978) of children in the classes involved in the analysis, based on the research experience in the Netherlands (cfr. Baerveldt et al., 2004). Each child was asked seven questions, constructed according to the name generator method, starting with a list of individuals who answered by indicating one or more schoolmates belonging to that list and identified by a number. Two of the questions concern emotional support measured mutually (Which pupils have you helped in hard times, such as in a conflict with other people, getting a bad mark or being taken for a ride? Which pupils helped you in hard times, such as in a conflict with other people, getting a bad mark or being taken for a ride?).One question measured the emotional support in one direction (Who do you talk to about personal problems?). Two questions measured the instrumental support mutually (Which pupils do you help with practical problems such as doing homework and projects or organizing a party? Which pupils help you with practical problems such as doing homework and projects or organizing a party?). One question related to a best friendship (Who are your best friends?) and another regarded negative relationships (Who do you avoid to stay with?). In practice, the case method calls for each student to indicate pupils within the class and this is why we deal with a complete network and direct graph. Although the questionnaire provides direct information concerning friendship through the item “Who are your best friends?”, a previous analysis revealed that friendship is not uniquely defined and experienced among kids. More specifically, girls seem to be less involved in friendships with class6 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS mates, in the sense of the number of people indicated as best friend (Rivellini et al., 2008). Also psychological literature on the topic tells us that, at this age, the females view friendships more introspectively, intimately and base them on verbal exchanges. As a consequence, friendships between girls are less focused on quantity and/or action, and more on the intensity and depth of the relationship. In other words, boys consider friendships in a more general way, while girls assign it a less generic meaning (Confalonieri et al., 2005; Petter, 2007). Consequently, it was considered more appropriate to use the question “Who do you talk to about personal problems?” as a proxy of friendship for the construction of the closed network. This limited the definition of friendship in this study to the emotional setting of exchange and confidence. We should also note that at the survey time, some students could be absent. The kids present in class could mention the missing ones, but clearly the potential reciprocal ties could not be gathered. For this reason the descriptive analysis was restricted only to a narrow number of classes (n=349) with respect to the total number of available classes (n=571) according to the percentage of students present (at least the 80%)10. The estimation of a statistical model (sec. 2.2) required a further reduction of the analysed data. Due to the rather time-consuming estimation process, only the province of Milan, with a total of 99 classes, was taken into account. This is not counterproductive for the results interpretation, since the province of Milan is a metropolitan area which encompasses a higher portion of foreign residents in Lombardy who attend public schools (the 45% in 2006, Blangiardo, 2007). Restricting the sample to only one province also has another statistical reason. Adding another source of variability at the provincial level implies modelling an additional source of variability which requires a complex definition of the model and of the related estimation procedure. A stochastic model makes it possible to investigate the regular patterns of complex social behaviours underlying the friendship process, taking into account random factors which derive from competing unknown explanatory variables. In addition, which structures play a key role in the global network configuration can be determined and their precise contributions can be quantified (Robins et al., 2007). For instance, clustering in networks could arise for two different reasons. The former depends on a “homophily” effect. The latter involves an endogenous balance type effect. Just to clarify, let us consider friendships among people. A subset of actors can be observed because they show the same characteristics, such as the same gender, ethnicity or status. Thus, friendship can be explained by a “likeness attraction” stated by the well-known social identity theory (Tajfel et al., 1979; Stets, 2000). This theory states that people have a spontaneous tendency to form groups since they need to recognize themselves as part of a group defined by a specific identity. The social identity stresses the differences 10 The classes excluded from the analysis show a slightly higher mean percentage of immigrant’s children (20.6%, vs. 18.1%) and a wider range ([0; 66.7] vs. [3.6; 66.7]). The percentage of mixed pupils is nearly equal to that of the classes included in the analysis (4.8% vs. 4.7%). 7 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI between the membership groups and the others, leading to clusters in the population and limiting the formation of ties among the people of a different group. If social identity is based on ethnic characteristics, then people will prefer intra-ethnic rather than inter-ethnic relationships. Another possibility to explain network clustering relies on the structural balance theory (Cartwright et al., 1956; Davis, 1963). It states that actors prefer to be related to people who are in turn related to themselves in order to avoid conflicts and tensions. For instance, this means that a person tends to establish friendships with friends of his/her friends. Thus, if these friends avoid inter-ethnic relationships, s/he will avoid them as well. If we want to distinguish between these two effects and determine their proper role, a stochastic model should be estimated, so that it is possible to evaluate the net contribution of each effect. 2.2 Choice of statistical model Statistical models analysing relational data aim to explain the presence of ties between two actors i and j on the basis of covariates measured at the actor (e.g. gender, ethnicity and so on) or dyadic (e.g. being in the same office, working together) level and the pattern of ties which give rise to the entire network structure (such as reciprocal dyads and triads). Although social network models have been proposed in the literature since 1951 (Solomonoff et al., 1951), interest in network modelling has increased since 1981, when Holland and Leinhardt introduced the well-known p1 model as a reaction to the “paucity of statistical tools available” for analyzing social network data (Holland et al., 1981). This model describes the presence of ties between a pair of actors assuming that there is independence among couples of actors and not taking into account covariates. For this reason in the 1990’s the p2 model was proposed as an extension of the p1 model (Lazega et al., 1997; Duijn et al., 2004). It allows for the inclusion of covariates but still assumes dyadic independence. Further steps are the Markov Graph Model (Frank et al., 1986) and its generalization, the Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM) which also overcomes the independence among dyads and introduces the idea of conditional dependence (Wasserman et al., 1996; Wasserman et al., 2005). All these models analyze one network at a time. Sometimes the same relationship is collected on different sets of actors so that there are several networks which should be investigated. Two major attempts to deal with multiple networks have been made in the literature. The former consists of estimating a model for each network and then applying a meta-analysis on the models coefficients (Lubbers, 2003; Baerveldt et al., 2004; Lubbers et al., 2007). The latter defines a multilevel model which properly takes into account the three-level hierarchical structure that arises in the case of multiple network observations (Zijlstra et al., 2006; Baerveldt et al., 2007; Vermeij et al., 2009): the ties (first level) which are nested in the actors (second level) who are embedded into the networks (third level). 8 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS The first approach can be applied both in the p2 model and the ERGM, while the second is currently implemented only for the p2 model. The structure of the available data naturally oriented the choice of the model towards a multilevel approach. In fact, classes and friendship relationships within students clearly defines multiple network observations. This means that each class constitutes a network which provides information about friendship mechanisms. Both of the methods previously outlined can be applied. On the one hand, the meta-analysis approach allows us to relax the independence assumption among dyads through the estimation of ERGMs, one per each network. This implies that more complex dependence structures can be included in the model specification. Among them, the literature on friendship relationships suggests that transitivity can be really important. This effect can be described using the well-known phrase “the friend of my friend is also my friend”. Some network studies proved its significant role in friendship relationships (Moody, 2001; Lubbers, 2003). On the other hand, the p2 multilevel model does not include complex dependence structures, but it allows for the analysis of all simultaneous and available networks, taking into account the variability within the networks, i.e. the variability between class networks which can be explained through specific class characteristics, as well as individual and dyadic characteristics. Thus, the choice between the two approaches relies on the importance given to the dependence hypothesis and to class traits. Since classes significantly differ in terms of number of students, gender, and ethnicity composition (Table 1), the multilevel p2 model seems to be more adequate, based on the currently available literature. Table 1 – Classroom composition (n=99). Province of Milan, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data 2.2.1 Formulating the model Let Y be a network defined by a dichotomous directed relationship col9 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI lected on a set of g actors. Y can be represented as a g x g adjacency matrix, whose generic cell yij takes value 1 if there is a tie between actor i and actor j and 0 otherwise. The couple of values Dij = (yij,yij) defines a dyad. Four different kinds of dyads can be identified. If there are no ties between i and j, the dyad is null (Dij = (0,0)); if there is only a tie between the two actors (from i to j or from j to i) the dyad is asymmetric (Dij = (1,0) or Dij = (0,1)); finally if both ties are present the dyad is reciprocal (Dij = (1,1)). The p2 model11 is a multinomial regression model which expresses the probability of observing one of the four possible outcomes of a dyad, according to endogenous network characteristics and actors covariates. The endogenous network characteristics include patterns of ties existing in the network. Examples of these are the number of outgoing ties (outdegree or density) and the reciprocal dyads. Actors’ covariates refer to individual attributes, such as gender, ethnicity, etc. This implies that social network models represent the global network configuration, taking into account both the properties of nodes and the pattern of ties existing among them. More specifically, the p2 model explicitly models the sender and receiver propensity according to individual attributes, as well as the density and the reciprocity effects according to dyadic explanatory variables. A positive effect of an individual or of a dyadic covariate can be interpreted as an increased probability that the tie exists. Let us look at each effect in more detail, describing it and explaining how to interpret the corresponding parameter. Sender and receiver effects. The sender effect is related to the wellknown concept of “expansiveness”, which is measured by the number of outgoing ties of a node and expresses the activity of a node in sending ties. This can be illustrated graphically by the exit lines (a directional line - arrow - for each classmate cited) sending from the node that represents a generic student. For instance, Figure 3 shows, how Student A is more expansive (more exit arrows) than Student B or Student C. Figure 3 – Three examples of graphical representation of expansiveness. 11 The statistical formulation of the model is described in Zijlstra et al., 2006. 10 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS On the other hand, the receiver effect refers to the “popularity” concept and it is measured by the number of incoming ties of a node. Thus, it interprets how much an actor is likely to be chosen as a termination of a relationship. This concept is illustrated by the arrows pointing to a node and Figure 4 shows that Student A, receiving two ties, is the least popular, while Student B is the most popular. Figure 4 – Three examples of graphical representation of popularity. Density and reciprocity effects. Density is defined as the number of lines existing in a network or as the ratio of the number of lines and the maximum number of possible ties which could be present in a network with g actors. For instance, Figure 5a represents a network which includes 6 nodes and 11 lines (arrows). There are two different kinds of parameter in the model which help in modelling the density. They are related to the overall density and dyadic effects. The parameter corresponding to the overall density effect can be interpreted as the log-odds of the probability of observing a tie. If it is negative, the probability of a relationship is smaller than 0.5 when all other parameters and the random effects are equal to zero. This indicates that networks are rather sparse (i.e. have low density). The presence of ties can also be explained by actors’ attributes, but since a tie involves a pair of nodes, the attributes of both actors should be considered. This explains why we have to use “dyadic-covariates” (instead of the individual covariates) to model the density. In more detail, dyadic covariates can be collected on pairs of actors or defined by actor attributes. In this second case, they are usually computed in terms of difference or absolute difference of actor attributes. A positive density effect of an absolute difference in gender suggests that a tie between two girls or two boys is less probable than a tie between a girl and a boy. Reciprocity is a more complex effect which measures the tendency towards symmetrical relationships (Figure 5b), as described in the previous paragraphs. Since it refers to pairs of ties it can be considered a sort of interaction effect. A positive value of the overall reciprocity parameter suggests that symmetrical dyads are more probable than asymmetrical ones. Reciprocity can also be modelled including dyadic covariates which can be interpreted similarly to those of density, with the only requirement being that dyadiclevel variables are modelled both for density and reciprocity. 11 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI Figure 5 – Density and reciprocity effects. Random effects. The multilevel approach also requires the introduction of random effects on both individual/actor and network levels (Zijlstra et al., 2006). They take into account and measure possible differences existing within networks or between the networks, respectively. More specifically, the differences within networks are taken into account including random effects at the sender and receiver level (i.e. at the actor level). If the sender and receiver variances are significant, it means that actors differ in their expansiveness and popularity tendencies. Regarding the relationship between sending and receiving ties, if the covariance is positive, then people who are more popular are also more expansive, while if it is negative there is a trade-off between sending and receiving ties. The differences between networks are modelled including random effects to density and reciprocity level (i.e. at the network level). If variances are significant, networks differ in density and reciprocity. Furthermore, if the covariance is positive it suggests that the denser the network, the higher the presence of reciprocal dyads. In order to estimate the parameters of the model it is convenient to use MCMC methods because the maximum likelihood estimation of the random effects requires the solution of intractable integrals (Zijlstra et al., 2009). The p2 model and its multilevel extensions are implemented in StOCNET (Boer et al., 2006). 3. DESCRIPTIVE RESULTS 3.1 Outside school friendship Before going into the core issues, we shall give a general overview gathered from survey data on pre-adolescent children of immigrants. Only onefifth of these kids were born in Italy, although that number rises to more than 30% if we take into account those who, born in another country, came to Italy 12 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS before starting school (i.e. before the age of 6). A slightly smaller percentage (27%) arrived in Italy less than three years prior to the survey after already completing part of their schooling in their country of origin. The main nationalities of origin reflect those of the adults, although the prevalence breakdown is different: Albanians, Moroccans, Chinese and Rumanians. Again, most of the kids live with their parents, whether Italian or of foreign origin. Their diversity lies in the size of the family. More often it is the foreigners who live in extended families (for economic reasons in most cases). Likewise, they have multiple siblings (more than 2) (see Casacchia et al., 2008). One final remark concerns the knowledge of the Italian language which is an essential tool for forming relationships outside a child’s community of origin. In this respect, the data samples show that, apart from the key role played by the length of time spent in Italy, some interesting differences emerge regarding immigrants’ fair knowledge of Italian. Pre-adolescents of African origin are those who apparently learn the language better; East Europeans seem to learn it more rapidly; as for Asians, learning is slower but in any case remarkable; the case of children from Latin America seems more problematic because, after an initial advantage (due to the similarity between the languages) they are often involved in forms of ethnic and linguistic resocialisation as a defence mechanism against forms of exclusion (see Gilardoni, 2008). We now focus on the core of the analysis. Firstly we consider a general description of the friendships outside school, as related by the kids. The ‘friendship strategy’ indicator shows that about 42% of foreign-origin kids can be labelled as “integrated”, by which we mean they have both Italian and foreign friends (whom they also see outside school). On the other hand, almost one-third see solely Italian friends (assimilation strategy) and, as a result, more than 70% of the foreign-origin preadolescents say they have good relationships with the Italians. We then find the less common case of the “segregated” - less than 20% - (i.e. those who say they have and see prevalently foreign friends) and, ultimately, the more problematic group made up of kids labelled “marginalised” (about 6%), i.e. those who say they have few or no friends, either Italian or of foreign origin. The scenario changes when we add other interpretative factors such as country of origin, socialization and gender. Looking at gender, Table 2 shows girls are at a disadvantage. They seem to be more marginalised, segregated and less integrated in friendships outside school. Regarding the country of origin, data suggest that kids of Asian origin experience the biggest difficulty in making friends, especially with Italians (Table 3), while the Africans are much more integrated or assimilated. 13 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI Table 2 – “Friendship strategy” of foreign pupils by gender. Lombardy, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data Incidentally, these differences are also influenced by the key role of socialization (Table 4): friendships grow and are consolidated the longer the kids spend in the host society. By this, we underscore that we do not mean an exclusion of friendships with the foreigners, but, to the contrary, an intensification of those with Italians. For instance slightly more than 40% of kids born in Italy identified themselves as assimilated, while among the kids socialized elsewhere, only 24% were assimilated. This, for example, might help explain the stronger assimilation of North Africans, the community with one of the longest migration traditions in Italy. On the other hand, if we consider Asian children, their stronger isolation is not mainly attributable to widespread socialisation having taken place abroad or even to difficulties caused by the substantial differences between languages, because these are apparently overcome soon after they have arrived in Italy. Among these kids other cultural factors (such as habits, traditions, values, belonging to more encapsulated communities) seem to have a greater impact on their relational behaviour (Dalla Zuanna et al., 2009). Table 3 – “Friendship strategy” of foreign pupils by origin. Lombardy, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data Table 4 – “Friendship strategy” of foreign pupils by socialization. Lombardy, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data 14 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS The same analyses, restricted to the classes surveyed in the province of Milan, were performed. The regional patterns described in the previous paragraphs were observed without any noteworthy differences (provincial results not shown). 3.2 Inside school friendship Considering friendships inside classrooms (through the question “Who do you talk to about personal problems?”, as we discussed in paragraph 2.1), we can now analyse how expansiveness and popularity change with respect to preadolescents’ characteristics. At this point, the Italian consolidated strategy of newcomer integration in schools plays a key role (see Mussino et al., 2012). Usually, a new foreign pupil is placed in one or more grades below his/her age group, assuming that this will give him/her more time to learn and will reduce the number of future exam failures. However, that proved to be an unsuccessful strategy, especially at the adolescent age (our case) and for establishing friendship ties within the class/grade. The diffusion of that strategy also emerges from the entire survey: among the foreign-origin kids attending lower secondary school at least half of them were one year behind, a fact that can be attributed not so much to failing their exams but more to the choice of which grade they are placed in upon arrival in Italy (see Casacchia et al., 2008). In addition, the data shows that the percentage of pupils who are at least two school years behind is definitely not marginal. In fact, in a class made up of 12-13 year olds, just under one-third of the foreign-origin pupils were aged about 15, an age at which it is consequently hard to forge ties and which carries a high risk of isolation. Moreover, we can observe that the more the pupil falls behind in school, the less importance they give to making friends with their classmates. Table 5 – Expansiveness and popularity by gender. Lombardy, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data 15 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI The analysis of expansiveness and popularity reveals that both gender and area of origin are discriminating factors. Table 5 shows that girls are more popular and more expansive with respect to boys, indicating that they express their personal problems more often than boys within the classroom setting. Similarly, Table 6 suggests that the Italians are more expansive, but, above all, more popular than the foreign kids. Among Italians less than one third showed low levels of expansiveness and popularity. Among children of foreign origin, there is a higher concentration in the lower levels (more than 40% show low expansiveness and almost the 50% also rates a low level of popularity). Kids of Eastern European and sub-Saharan African origin are the most expansive, scoring similarly to the Italians. Vice-versa, the less expansive peers are the Asian (already noted as those also experiencing greater relational difficulties outside school) and the students from Latin America. We need to remember that the arrivals just before the survey date (2006) are largely made up of these latter, triggering adaptation difficulties. In terms of popularity (mainly lower than the levels of expansiveness regardless of origin), the kids of Eastern Europe and sub-Sahara origin are more successful in becoming popular among their classmates. On the other hand, the lowest levels of popularity were scored not only by Latin Americans and Asians (mainly due to the reasons indicated earlier), but also by the African-origin pupils. The fall in this latter group compared with expansiveness can possibly be explained by the diffusion of negative stereotypes in Italian society about people from Islamic countries. In an “intermediate” position regarding friendship relationships in the classroom, there are students of mixed origin (i.e. with one Italian and one foreign parent). These kids are not as unpopular as the foreigners, although they are less sought after than Italians; on the other hand their activism in friendship is comparable to that of the most active foreigners in the classroom. Table 6 – Expansiveness and popularity by origin. Lombardy, 2006 EE = Eastern Europe, A = Asia, NA= North Africa, SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa, LA = Latin America, M = Mixed, I = Italian Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data 16 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS Finally, the role played by socialization is pointed out again (Table 7). Kids who fully socialize in Italy score similarly in the popularity and expansiveness to the Italian pupils. Therefore, the more time a person spent in the growth and training phase outside Italy, the less likely they are open up to others or chosen as a friend by other classmates. For example, those who were socialized “elsewhere” in most cases score low on expansiveness (52.8%), but even more remarkably low on popularity (62%). Table 7 – Expansiveness and popularity by socialization. Lombardy, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data We conclude the descriptive part with some useful considerations about the concept of homogeneity, trying to identify who chooses whom and if similar pupils attract or reject each other. Here, we focus on two aspects: the ties of gender; and the ties of origin. In terms of gender, it is clear that at this age friendships develop mainly between individuals of the same gender: boys say they have prevalently other boys as friends and, likewise, girls say they have mainly other girls as friends, revealing closure with respect to gender. Table 8 – Homogeneity by gender. Lombardy, 2006 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data Regardless of their area of origin, the children clearly show a predominance of friendship relationships with Italians. This tendency can be justified mainly by the natural prevalence of Italian kids in the classes (see Table 1). Another interesting result is that Italians are more involved in mixed friend17 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI ship relationships with sub-Saharan Africans and less with Asians. The friendship relationships between foreigners with the same origin are not frequent (the highest score, 15.5%, is registered among Asians who, as already noted, tend to interact with peers of the same origin more than with other foreigners) due to the low percentage of foreigners in the classes, in particular of the same nationality. Similarly, Italian kids are less involved in inter-ethnic ties. Table 9 – Homogeneity by area of origin. Lombardy, 2006 EE = Eastern Europe, A = Asia, NA= North Africa, SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa, LA = Latin America, M = Mixed, I = Italian Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data In this case, the analyses performed on the province of Milan reveal some differences. It is noteworthy that the distribution of expansiveness both for boys and girls is slightly more concentrated on low and medium values, while for popularity no clear differences appear between province and region (provincial results not shown). Furthermore, the homogeneity analysis by area of origin underlines a higher preference of East-European children in making friendship with classmates of the same origin. Such differences are mainly attributable to a more diverse composition by area of origin of the respondents at regional level, compared to the provincial area. This is due to the difference in the size of the groups in the two territorial areas. This is the reason for introducing the area of origin covariate as part of the model illustrated in the following section. 4. RESULTS OF NETWORK MODEL ESTIMATION To validate the results deriving from the descriptive analysis, a p2 multilevel model was estimated from the 99 classes (networks) surveyed in the province of Milan. There were 1,961 children considered in the analysis. Among them, 49.8% are boys, 20.5 % are children of immigrants and 5.5% are mixed pupils. The model includes the overall network parameter related to density and reciprocity, as well as dyadic and individual effects. At the dyadic level, covariates connected to gender and area of origin were considered in order to test the existence of homophily with respect to these attributes. Given the variety of geo- 18 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS graphic regions from which the students stemmed, the area of origin was codified into three categories, distinguishing among Italians, foreigners (both parents born in CHEL) and mixed-origin pupils. The codification prevents the introduction of too many dummy variables and also solves the problem related to the ethnic composition of the classes. Given the variety of migrants’ citizenships on Italian soil, it was unlikely that two or more children of migrants coming from the same country or national area attended the same classes. At the actor level, some variables were considered to investigate the sender and receiver attitudes. Previous descriptive analysis showed that gender and socialization can be potential explanatory variables for expansiveness and popularity. To test if boys and girls really adopt different strategies in making friends and if the time of arrival in Italy influences friendship relationships, gender and socialization were included in the model12. Finally we checked the importance of school friends. It is well-known that building and maintaining a relationship involves both costs and benefits. We can assume that higher the importance given to friendship with classmates, the higher the perceived benefit. Thus, we expect that kids who believe in the relevance of having friends at school are more encouraged to both make (sending) and be (receiving) in friendship relationships. Nevertheless, without longitudinal data, we cannot investigate any causal relationship between being active and popular and the importance of having friends in school. Finally, the random effects were included in the model both at the actor and network level. The estimates of the p2 model are contained in Table 10. The negative value of the density parameter (-3.673, p-value < 0.01) shows that the probability of the existence of a confidential friendship relationship between peers is less than 0.5, when all the other effects (random and not random) are equal to zero. This finding is consistent with the very low values of network density (density values vary between 0.0254 and 0.6176 with a positive skewed distribution). There is a high tendency towards reciprocal choice among the few existing ties, as suggested by the positive estimate of the reciprocity parameter (3.026, p-value < 0.01). In other words, there are few confidential friendship relationships but they tend to be symmetrical defining an out-and-out relationship of blind trust. The estimates associated with the dyadic covariates support the thesis that gender and ethnicity (area of origin) are associated with homophily, as revealed by the descriptive analysis. More specifically, the negative effect of 12 According to the Italian strategy of newcomer integration, described in the previous paragraph, we should include in the model also the age gap in those pupils who are placed in classes that do not correspond to their age. In fact, different ages mean different needs and this could obstruct the arising of friendship relations. Since the variable related to the delay in age is highly associated to the socialization (x2=491.94, df=4, p-value < 0.001), this variable was omitted. 19 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI the absolute difference in gender (-1.780, p-value < 0.01) indicates that the probability of observing a dyad decreases as the difference between the two actors increases. This effect is also reinforced by the positive value of the gender reciprocity parameter (1.047, p-value < 0.01). Regarding ethnicity, a different pattern is observed. The density coefficient is negative for the foreign pupils, but positive for the mixed (-0.402 vs. 0.235, p-value < 0.01), suggesting that the former are less involved in friendship relationships than the latter. The reciprocity coefficient is significant only for the mixed peers (-0.545, pvalue < 0.01) who prefer children/pupils of mixed couples. At the actor level, gender, socialization and importance of friends at school only play a partial role. Regarding gender, girls are more popular than boys (0.437, p-value < 0.01) and entrust more personal matters in their friendships, while no gender difference arises according to the sender attitude. The same pattern is observed with regard to socialization. In this case, pupils that arrived after their tenth birthday are less popular then children who came to Italy in pre-school ages, as pointed out by the negative coefficient associated to socialization (-0.628, p-value < 0.01). The high importance given to the schoolmates as friends is significant both for the sender and for the receiver (0.584 and 0.414 respectively, p-value < 0.01). In particular the positive association between the high importance and the expansiveness/popularity indicates that pupils who considered classmates very important are more involved in confidential relationships. Finally, the model provides random effects. The three actor-level effects are statistically significant indicating that actors differ both in popularity and the expansiveness attitude. Furthermore, the negative value (-0.472, p-value < 0.01) of the covariance between these two tendencies shows that the more popular a pupil is, the less expansive he/she is. Thus, the less expansive peers are seen as perfect secret keepers and, for this reason, they are chosen by a higher number of people as confidant. At the network-level, the parameter estimates suggest that networks differ in the presence of ties (the density variance is significantly different from zero), while no differences related to reciprocity are observed. The covariance between these two structural properties is positive (0.202), revealing that networks with low density are characterized by a higher tendency towards reciprocal ties. In other words, one can say that a lower number of relationships means more consolidated ties. 20 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS Table 10 – Coefficients and standard errors of p2 multilevel model. Province of Milan, 2006. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01 Source: Processing of Lombardy ITAGEN2 data 21 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI 5. CONCLUSIONS The analysis of friendships inside and outside the classroom proved useful in order to study the social integration of immigrants’ teenage children. It was observed that immigrants’ children are often less popular or more isolated within an important reference group, such as the class they attend. On the other hand, some individual characteristics, such as their migration history, may affect their relational situations. For example, greater difficulties in being integrated among children of the same age are more often due to cultural factors among Asians, to a longer socialization outside of Italy, as in the case of Latin Americans, or to a more discriminatory attitude towards people from North Africa, as shown by the more limited likelihood of being chosen as confidant among classmates. Other individual and relational characteristics affect the pupils’ way of interacting. Descriptive analysis shows that girls and boys clearly differ in the friendship formation. The relational approach (more or less expansive/more or less popular) varies depending on the friendship definition underlying the question posed. The more one focuses on the confidential/intimate dimension of the relationship (friends regarded as persons with whom you can talk), the more girls stand out. On the other hand, the more generic the definition of friendship (friends seen as playmates, for example), the more boys are indicated as friends. Subsequently regarding the question analysed in this paper, it appears that while boys are less expansive and popular, girls are more active in making close and intimate friendship relationships among classmates. This difference, however, should not be entirely interpreted as a male disadvantage or shortcoming. On the one hand, it is necessary to explore more specifically the different dimensions of friendship (frequency of meetings, intimacy achieved and mutual exchange of material and psychological support). On the other hand, it would be important to consider the individual view of friendship. Nevertheless, the network analysis highlighted that the existence of a friendship tie is explained not only by the individual characteristics of the kids observed as independent entities. One should also consider the features associated with the pair of actors and the overall structure of the network which can influence a friendship relationship (endogenous feedback). For example, considering homophily with respect to gender and area of origin, intra-gender and intra-ethnic tendencies clearly emerge, confirming the identity theory. In general, descriptive results are confirmed by the model estimation: the intimate friendship relationships mainly consist of pairs or components which are not numerous, but they are characterized by a higher tendency towards reciprocity. In the case of a relationship between two individuals, the model highlights the closure with respect to gender (reinforced also by the reciprocity effect) and the inter-ethnic traits. Friendship relationships are more likely among those of similar origin than between foreign and mixed pupils. In par22 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS ticular, homophily characterizes the relationships among the former but not the ties among the latter. No difference in the sender attitude (expansiveness) is related to gender and socialization, while they are statistically significant in explaining popularity. There are no differences in the tendency to look for friends, but there are differences in being chosen as a close friend. Furthermore, there is a negative trend between expansiveness and popularity as stated by the actor-level random effects. This suggests that pupils who declare that they have a lot of friends are less frequently chosen by others as friends. Thus, someone who talks about personal problems with a lot of other classmates is considered not a good confidant, since s/he can reveal to other classmates, who trust and are close to him/her, the confidential conversation that s/he had with others. The confidential friendship relationships examined here are, therefore, rare but deep, consolidated and mutual. This means that with this kind of question the balance theory can not be supported because intimate relationships by their own nature prefer smaller groups. In this age group, children prefer to establish ties with those who can keep a secret and will not betray the trust of the confidant; these are characteristics more frequently associated with girls. The social network perspective revealed interesting results and also suggested the need for more in depth exploration. In particular, it was observed that one question is not enough to discover and describe real friendship. Therefore, a step forward would require the use of other network questions about the sphere of emotional support. With this addition, a multi-relational analysis would provide a solution to jointly analyze more than one concurrent relationship and a key for studying integration among peers. Having more than one network calls for an extension of the multilevel model to a multi-relational approach. This extension still requires work in theoretical and computational settings, since the hierarchical structure of the data should be taken into account for each relationship, making the model more complex. For this reason, a multilevel approach has yet not been extended to multi-relational data. As suggested by the opportunity theory, the school can be a privileged place where friendships are created and reinforced. This may help immigrants’ children feel less marginalized. It is therefore important to guarantee easy access and high quality at all educational institutions open to a diverse (in terms of origin and migration history) student body. It is also important to foster schools as venues where teachers, cultural mediators and families can work together in order to enhance inter-ethnic socialisation among children as well as adults because the latter will have a positive spill over effect on the pupils. The context of potential social integration for preadolescents, however, can be wider than just the scholastic environment. We should take into account the relevance of other environments, such as sports, in which preadolescents often stay together in a group, and exhibit attitudes and conduct themselves differently from the school environment. 23 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI Finally, social integration is - by its very nature - a process which might take a very long time to complete and which is affected in different ways by individual characteristics. Only longitudinal data, therefore, make it possible to observe the dynamics of this process. However, it is necessary to bear in mind that the process can be accelerated with a positive effect by actions targeted to specific groups of children of different origins, taking into account their migratory histories and cultural backgrounds. References (2009), Le determinanti dei legami intra-etnici: uno studio basato sulla network analysis, Giornate di studio sulla popolazione, Milan, February 2-4. BAERVELDT C., VAN DUIJN M.A.J., VERMEIJ L., VAN HEMERT D.A. (2004), “Ethnic boundaries and personal choice. Assessing the influence of individual inclinations to choose intra-ethnic relations on pupils’ networks”, Social Networks, 26, 55-74. BAERVELDT C., ZIJLSTRA B., DE WOLF M., VAN ROSSEM R., VAN DUIJN M. (2007), “Ethnic boundaries in high school students’ networks in Flanders and the Netherlands”, International Sociology, 22, 701-720. BERRY J.W. (2001), “A psychology of immigration”, Journal of Social Issues, 57, 615-631. BLANGIARDO G. C. (2007) (eds.), L’immigrazione straniera in Lombardia, Sesta indagine regionale, Fondazione Ismu, Milano. BOER P., HUISMAN M., SNIJDERS T., STEGLICH C., WICHERS L., ZEGGELINK E. (2006), StOCNET: An open software system for the advanced statistical analysis of social networks. Version 1.7. Groningen, The Netherlands: ICS/Science Plus. BRANDES U., WAGNER D. (2004), “Visone - Analysis and visualization of social networks”, in JÜNGER M., MUTZEL P. , Graph Drawing Software, Springer-Verlag. CANEVA E. (2011), Mix generation. Gli adolescenti di origine straniera tra globale e locale, Franco Angeli, Milano. CASACCHIA O., NATALE L., PATERNO A., TERZERA L. (2008) (eds.), Studiare insieme, crescere insieme? Un’indagine sulle seconde generazioni in dieci regioni italiane, Franco Angeli, Milano. CASACCHIA O., NATALE L., GUARNERI A. (2009) (eds), Tra i banchi di scuola. Alunni stranieri e italiani a Roma e nel Lazio, Franco Angeli, Milano. CARTWRIGHT D., HARARY F. (1956), “Structural Balance: A Generalization of Heider’s Theory”, Psychological Review, 63, 277-93. AMATI V. 24 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS (2005), Adolescenza e compiti di sviluppo, Unicopli, Milano. CRUL M., VERMEULEN H. (2003), “The second generation in Europe”, International Migration Review, 37, 965-986. DALLA ZUANNA G. (2008), “Nota metodologica, in CASACCHIA O., NATALE L., PATERNO A., TERZERA L., Studiare insieme, crescere insieme? Un’indagine sulle seconde generazioni in dieci regioni italiane, Franco Angeli, Milano. DALLA ZUANNA G., FARINA P., STROZZA S. (2009), Nuovi italiani. I giovani immigrati cambieranno il nostro paese?, Il Mulino, Bologna. DAVIS J.A. (1963), “Structural balance, mechanical solidarity, and interpersonal relations”, American Journal of Sociology, 68, 444-462. DUIJN M., SNIJDERS T., ZIJLSTRA B. (2004), “p2: a random effects model with covariates for directed graphs”, Statistica Neerlandica, 58, 234-254. FARINA P., TERZERA L. (2007), L’integrazione delle seconde generazioni in Italia, Rapporto di ricerca, Roma, Ministero della Solidarietà sociale. FONDAZIONE ISMU (2010), Quindicesimo rapporto sulle migrazioni 2009, Franco Angeli, Milano. FRANK O., STRAUSS D. (1986), “Markov Graphs”, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81, 832-842. GILARDONI G. (2008), Somiglianze e differenze. L’integrazione delle nuove generazioni nella società multietnica, Franco Angeli, Milano. HALLINAN M. (1982), “Classroom racial composition and children’s friendships”, Social Forces, 61, 56-72. HALLINAN M., TEXEIRA R.A. (1987), “Opportunities and constraints: BlackWhite Differences in the Formation of Interracial Friendships”, Child Development, 58, 1358-1371. HOLLAND P., LEINHARDT S. (1981), “An exponential family of probability distributions for directed graphs”, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76, 33-50. ISTAT (2010), La popolazione straniera residente in Italia al 1° gennaio 2010, Statistiche in breve, Rome, 12 October 2010. LAZEGA E., VAN DUIJN M. (1997), “Position in formal structure, personal characteristics and choices of advisors in a law firm: A logistic regression model for dyadic network data”, Social Networks, 19, 375-397. LUBBERS M. (2003), “Group composition and network structure in school classes: a multilevel application of the p* model”, Social Networks, 25, 309-332. LUBBERS M., SNIJDERS T. (2007), “A comparison of various approaches to the exponential random graph model: A reanalysis of 102 student networks in school classes”, Social Networks, 29, 489-507. CONFALONIERI E., GRAZZANI GAVAZZI I. 25 GIULIA RIVELLINI – LAURA TERZERA – VIVIANA AMATI (1978), “A procedure for surveying social networks”, Sociological Methods & Research, 7, 131-148. MCPHERSON M., SMITH-LOVIN L., COOK J.M. (2001), “Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks”, Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415444. MOODY J. (2001), “Race, School Integration, and Friendship Segregation in America”, American Journal of Sociology, 107, 679-716. MUSSINO E., STROZZA S., (2012), “The Delayed School Progress of the Children of Immigrants in Lower-Secondary Education in Italy», Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38, 41-57. PATERNO A., TERZERA L. (2008), “Foto di classe in giro per l’Italia”, in CASACCHIA O., NATALE L., PATERNO A., TERZERA L., Studiare insieme, crescere insieme? Un’indagine sulle seconde generazioni in dieci regioni italiane, Franco Angeli, Milano. PETTER G. (2007), Innamoramento e amicizia in adolescenza, Giunti, Firenze. RIVELLINI G. (2007), “Le reti di relazioni dei bambini italiani e stranieri in un’ottica di integrazione. Considerazioni da un’indagine esplorativa”, in SALVINI A., Analisi delle reti sociali. Teorie, metodi, applicazioni, Franco Angeli, Milano. RIVELLINI G., TERZERA L. (2008), Schoolmates…but also friends? Analysis of Closed Friendship Networks between Italian and Foreign pupils, presented at the EPC, Barcelona, July 9-12. ROBINS G., PATTISON P., KALISH Y., LUSHER, D. (2007), “An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks”, Social Networks, 29, 173-191. RUMBAUT R. (1994), “The crucible within: ethnic identity, self-esteem and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants”, International Migration Review, 28, 748-794. SCOTT J. (2007), Social network analysis: A handbook, Sage, London SHRUM W., CHEEK JR N.H., MACD S. (1988), “Friendship in school: gender and racial homophily”, Sociology of Education, 61, 227-239. SOLOMONOFF R., RAPOPORT A. (1951), “Connectivity of random nets”, Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 13,107-117. STETS J.E., BURKE P.J. (2000), “Identity theory and social identity theory”, Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 224-237. TAJFEL H. E. TURNER J.C. (1979), “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict”, in AUSTIN W. G., WORCHEL S., The social psychology of intergroup relationships, Brooks-Cole, Monterey, CA. TERZERA L. (2010), “From workforce to population: processes of settlement of immigrants in Italy”, Rivista Italiana di Economia Demografia e Statistica, vol. LXIV, 3. MCCALLISTER L., FISHER C. 26 INDIVIDUAL, DYADIC AND NETWORK EFFECTS IN FRIENDSHIP RELATIONSHIPS THOMSON M., CRUL M. (2007), “The Second Generation in Europe and the United States: How is the Transatlantic Debate Relevant for Further Research on the European Second Generation?”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33, 1025-1041. VERMEIJ L., VAN DUIJN M., BAERVELDT C. (2009), “Ethnic segregation in context: Social discrimination among native Dutch pupils and their ethnic minority classmates”, Social Networks, 31, 230-239. WASSERMAN S., FAUST K. (1994), Social network analysis: Methods and applications, Cambridge University Press. WASSERMAN S., PATTISON P. (1996), “Logit models and logistic regressions for social networks: I. An introduction to Markov graphs and p*”, Psychometrika, 61, 401-425. WASSERMAN S., ROBINS G. (2005) “An introduction to random graphs, dependence graphs, and p*”, in CARRINGTON P.J., SCOTT J., WASSERMAN F., Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis, Cambridge University Press, New York. ZIJLSTRA B., VAN DUIJN M., SNIJDERS T. (2006), “The multilevel p2 model”, Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2, 42-47. ZIJLSTRA B., VAN DUIJN M., SNIJDERS T. (2009), “MCMC estimation for the p2 network regression model with crossed random effects”, British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 62, 143-166. 27