* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Responding to the Stubbornly Steep U.S. Treasury Yield Curve

Financial economics wikipedia , lookup

Securitization wikipedia , lookup

Investment fund wikipedia , lookup

Financialization wikipedia , lookup

Present value wikipedia , lookup

Federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate swap wikipedia , lookup

Interbank lending market wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate ceiling wikipedia , lookup

United States Treasury security wikipedia , lookup

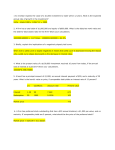

Weekly Market U pdate FEBRUARY 14, 2011 Responding to the Stubbornly Steep U.S. Treasury Yield Curve Disciplined, active investment managers are constantly on the lookout for capital market extremes, which can provide value-adding opportunities for investors. One such market extreme has been developing in the U.S. Treasury market for the past three years, reaching historic levels in 2010 and earlier this year. We’re talking about the very wide, stubbornly persistent gap between short- and longer-maturity U.S. Treasury yields. This market extreme is also known as the “steep U.S. Treasury yield curve.” Picturing a Steep Treasury Yield Curve The U.S. Treasury yield curve is simply a graph showing the yields of Treasury securities of different maturities at a given point in time. For example, as of the U.S. bond market’s close on February 4, 2011, U.S. Treasury securities of the following maturities had these corresponding yields: • 2 years: 0.76% The U.S. Treasury yield curve is simply a graph showing the • 5 years: 2.28% • 10 years: 3.65% • 30 years: 4.74% T Plotting these yields and maturities on a graph, and connecting them with a line, looks like this: S L A yields of Treasury securities of A Wide Yield Gap and Steep Upward Slope S different maturities at a given U.S. Treasury Yield Curve: Feb. 4, 2011 L C 5.0% point in time. 2/4/2011 Treasury Yields (%) 4.5% 4.0% 3.5% 3.0% 2.5% 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0.5% 0.0% 0 5 10 15 Treasury Maturities (Years) Source: Bloomberg 20 25 30 Weekly Market U pdate The present “steepness” of the U.S. Treasury yield curve derives from the steep upward slope of the line connecting the yields. This results from a relatively wide gap of approximately four full percentage points between two- and 30-year yields. Historically, that gap has averaged less than half that amount. What Does the Historically Steep Treasury Yield Curve Tell Us? The Treasury yield curve is widely considered an important leading economic indicator. That’s because its shape and slope can tell us much about the market’s economic expectations, particularly with regard to interest rates and inflation. An upward-sloping yield curve is typically a harbinger of stronger economic growth, rising inflation, and higher interest rates. For example, the presently steep upward slope of the U.S. Treasury yield curve is based largely on the following current conditions and market expectations: The Treasury yield curve is widely considered an important leading economic indicator. That’s because its shape and slope can tell us much about the market’s economic expectations, particularly with regard to interest rates and inflation. • The historically low level of the Federal Reserve’s (the Fed’s) short-term interest rate target. The short-maturity end of the Treasury yield curve is often said to be “anchored by Fed interest rate policy.” Since December 2008, the Fed’s overnight interest rate target has been 0–0.25%, a historic low. This low rate was in response to the credit crisis and Great Recession, designed to lower the cost of money, stimulate lending and investment, and promote economic growth. This rate establishes the level for most other U.S. short-term interest rates and yields, including the prime lending rate for banks, money market yields, interest rates on certificates of deposit, and the two-year Treasury yield. As long as the Fed views recession and deflation as a greater potential threat to the U.S. economy than inflation, it will keep its rate target low. • Expectations that Fed and U.S. government policies to stimulate the economy could eventually be inflationary in the longer term. The sheer magnitude of the Fed’s and the U.S. government’s stimulative monetary and fiscal policies in the wake of the credit crisis and Great Recession have fueled inflationary expectations. For example, the Fed’s low interest rate policy described above helped end the crisis and recession, but at the risk of inflating other asset bubbles—possibly in commodities and stocks—similar to the housing and finance bubbles that led to the crisis and recession. Aggressively low interest rate policies also risk devaluing the U.S. dollar and fueling significantly higher “imported inflation” down the road. Inflation expectations are among the key risk factors priced into longer-maturity Treasury yields—whenever you see longer-maturity Treasury yields that are significantly higher than shorter-maturity yields, you can typically assume that higher inflation expectations have been priced in. Picturing the Relative Magnitude and Persistence of the Latest Steep Curve Two factors that distinguish this particular period of Treasury yield curve steepness are: 1. Magnitude. The yield gap between two- and 30-year Treasury securities had never before broached 4.0 percentage points. 2. Persistence. Instead of broaching 3.5 percentage points for a short time and then declining, as it did following the recessions in 1990-91 and 2001, the yield gap peaked twice more in the latest period and has remained near 4.0 percentage points. 2 Weekly Market U pdate These distinguishing factors are displayed in the following graph, which puts the latest curve steepness into a larger historical context, over the last 22 years: The Latest Yield Gap Has Been Wider for a Longer Period 2- to 30-Year Treasury Yield Gaps: Feb. 1989 to Feb. 2011 Yield Gap (Percentage Points) 5.00 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 0.00 level of steepness, what’s most likely to happen next, statistically, is that the Treasury yield curve should eventually start to flatten. Feb 11 Feb 10 Feb 09 Feb 08 Feb 07 Feb 06 Feb 05 Feb 04 Feb 03 Feb 02 Feb 01 Feb 00 Feb 99 Feb 98 Feb 97 Feb 96 Feb 95 Feb 94 Feb 93 Feb 92 Feb 91 Feb 90 At this extreme, historic Feb 89 -1.00 Date Source: Bloomberg Why did the Treasury yield gap recently exceed 4.0 percentage points for the first time and stay stubbornly above 3.5 percentage points? Blame primarily the Great Recession and its aftermath. As we mentioned earlier, the short-maturity end of the curve has been anchored by the Fed’s refusal since 2008 to change interest rates, which could continue until 2012. Meanwhile, since September 2008, the Fed and the U.S. government have also unleashed additional, unprecedented levels of stimulative measures on the U.S. economy, financed largely by soaring federal debt levels and increased Treasury debt issuance. This has put devaluation pressures on the U.S. dollar and stoked future inflation fears. All those risk pressures on long-maturity Treasuries, combined with the Fed’s interest rate lock-down at the short-maturity end of the spectrum, has helped produce an environment conducive to a larger, more-extended yield gap. What Could Change the Slope of the Treasury Yield Curve? At this extreme, historic level of steepness, what’s most likely to happen next, statistically, is that the Treasury yield curve should eventually start to flatten, as we can see from what happened after curve steepness peaked in October 1992 and July 2003. This typically can occur in a couple of ways: • A “bear flattener.” This is when the Treasury market anticipates that the Fed will begin raising its overnight interest rate target, and begins pricing in significantly higher short-maturity yields. This is a “bearish” scenario because the upward adjustment in yields usually translates to price declines for most fixed income securities. Meanwhile, longer-term yields may also move up, but they generally hold relatively steadier than short-maturity yields as the Fed’s actions are perceived to be a start in the direction of addressing long-term inflation threats. This is typically the most common yield curve flattening scenario at the point we’re now in during the business cycle, when the Fed is poised to raise its interest rate target after years of low rates. 3 Weekly Market U pdate Active investment managers, such as those at American Century Investments, have been looking at potential changes in the extreme, historically steep Treasury yield curve as an opportunity to add value for clients. •A “bull flattener.” This is when economic weakness, a declining threat of inflation ahead, and/or a geopolitical or financial threat that feeds a flight to credit safety drives bond buyers/safety seekers back to the longer-maturity end of the Treasury market, causing longer-maturity Treasury yields to decline more than shorter-maturity yields. This is a “bullish” scenario for bonds because Treasury prices typically increase under this scenario. This scenario can occur—as it did in the middle of 2010—when a recovering economy is still finding its legs and suffers a temporary setback or threat. Last year, it was primarily the European sovereign debt crisis that caused the mid-year bull flattener. This year it could potentially be the revolutionary turmoil in the Middle East, sharply higher oil prices, or some other similar disruption. Applying Curve Expectations to Active Fixed Income Strategies Active investment managers, such as those at American Century Investments, have been looking at potential changes in the extreme, historically steep Treasury yield curve as an opportunity to add value for clients, particularly at a time when bond yields are relatively low and the risk of bond price declines from rising interest rates has increased. While past performance is no guarantee of future results, and it’s still possible that the curve could steepen further, American Century Investments’ fixed income team believes strongly that over the next few years, the most likely yield curve behavior will be flattening, accompanied by narrower Treasury yield gaps. Based on this conviction, our fixed income team began implementing small, incremental “yield curve flattening bias” trades in bond portfolios in 2009. The Treasury yield curve version of this strategy involves selling two-year Treasury futures short (anticipating declines in value as interest rates rise) and buying 30-year Treasury futures long. (For shorter maturity/duration portfolios, the fixed income team sells two-year Treasury futures short and buys five-year futures long.) The goal is to achieve a certain percentage of positive portfolio return for every curve flattening move. It doesn’t matter if it’s a bear flattener or a bull flattener. For example, the mid-year bull flattener enhanced American Century bond portfolio returns during 2010. But, conversely, resurgent yield curve steepening in the fourth quarter of 2010 counteracted those gains. Curve changes can be volatile and unpredictable in the nearterm, particularly at inflection points for the economy. This positioning requires long-term conviction and commitment to succeed. What Does All This Mean for Investors? The increasing likelihood of Treasury yield curve flattening and higher interest rates and yields across the maturity spectrum in the coming two to three years means looking at fixed income portfolios and evaluating how they are positioned and managed for that longer-term scenario. It’s worth noting that actively managed portfolios that pursue yield curve strategies can supplement more typical duration, sector, and credit management strategies. As economic conditions improve and bond portfolios face more inflation and interest rate challenges, it’s a good time to assess what tools fixed income managers have ready and available in their toolboxes. 4 Weekly Market U pdate Past performance is no assurance of future results. Investment return and principal value will fluctuate, and it is possible to lose money by investing. In addition, generally, as interest rates rise, bond prices fall. You should consider a fund’s investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses carefully before you invest. The fund’s prospectus or summary prospectus, which can be obtained by visiting americancentury.com, contains this and other information about the fund, and should be read carefully before investing. Investments are subject to market risk. The opinions expressed are those of American Century Investments and are no guarantee of the future performance of any American Century Investments portfolio. This information is not intended to serve as investment advice; it is for educational purposes only. ©2011 American Century Proprietary Holdings, Inc. All rights reserved. IN-FLY-70881 1102