* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

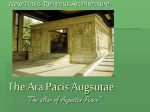

Download Aeneas or Numa? Rethinking the Meaning of the Ara Pacis

Marriage in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman calendar wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

The Last Legion wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Augustus wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup