* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Effect of Prophylaxis on the Clinical Manifestations of AIDS

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

Sarcocystis wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Anaerobic infection wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

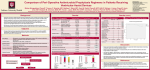

806 AIDS COMMENTARY Effect of Prophylaxis on the Clinical Manifestations of AIDS-Related Opportunistic Infections Kent A. Sepkowitz From the Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York Introduction. The availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy has altered the epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus infection among individuals with access to medical care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other public health authorities have reported decreases in both morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected patients. As Dr. Sepkowitz documents, however, opportunistic infections continue to occur in spite of antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis. ‘‘Breakthrough’’ infections often present atypically, and thus the clinician must be alert to the changing picture of common infections impacting patients with advanced immunosuppression. Dr. Sepkowitz has reviewed the available literature and suggests a need to continue to document the atypical presentations of common opportunistic diseases in these patients. — John P. Phair Administration of targeted prophylaxis for AIDS-related opportunistic infections has contributed significantly to the recent decrease in mortality among patients with AIDS in the United States. Most reported prophylaxis trials have focused on determining (a) the percentage of cases prevented and (b) the effect of widespread antibiotic use on drug susceptibility. A third phenomenon that is seldom reported on is the attenuating effect of failed prophylaxis on the clinical presentation of opportunistic infections (OIs). With the increasingly widespread use of prophylaxis for OIs, more atypical ‘‘breakthrough’’ cases of opportunistic infections will be seen. Reports of clinical changes are reviewed below. Investigators should routinely report the clinical manifestations of breakthrough cases in all articles pertaining to prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in patients with AIDS. In 1996, 68,473 new cases of AIDS were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), including 29,227 (43%) due to AIDS-indicator conditions [1]. Overall, the CDC estimates that Ç60,000 AIDS-related opportunistic illnesses have occurred each year in the United States since 1992. Despite the large number of opportunistic conditions and the bewildering array of diseases described, most illness is caused by a relatively small handful of pathogens, including Pneumocystis carinii, cytomegalovirus, various fungi, and mycobacteria; conditions such as the wasting syndrome and dementia; and neoplastic diseases, including Kaposi’s sarcoma and lymphoma. Therefore, in 1995, the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) issued guidelines for prevention of opportunistic infec- Received 21 November 1997. Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Kent A. Sepkowitz, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, Box 288, New York, New York 10021. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1998;26:806–10 q 1998 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058–4838/98/2604–0002$03.00 / 9c4a$$ap07 03-12-98 08:31:23 tions (OIs) in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [2], which were updated in 1997 [3]. The strongest recommendations concerned strategies to prevent Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and infections due to Toxoplasma gondii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. avium complex (MAC), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and varicella zoster virus [3]. Routine prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus, candidal, and endemic fungal diseases was considered indicated only in unusual circumstances. Secondary prophylaxis was strongly recommended for PCP and infections with T. gondii, MAC, cytomegalovirus, Salmonella species, Cryptococcus neoformans, and endemic fungi [3]. Despite targeted and effective prophylaxis and despite the effect of potent antiviral therapies on the type and frequency of hospital admissions [4 – 6], opportunistic infections continue to occur. Most reports of trials examining a specific approach to the prevention of an opportunistic infection (prophylaxis studies) focus on two outcomes of interest: (1) the quantitative effect, i.e., how many cases were prevented, and (2) the microbiological effect, i.e., the susceptibility profile of breakthrough cases. Few, however, have examined the third effect of prophylaxis: the clinical presentation of prophylactic failures, or the qualitative effect. cidas UC: CID CID 1998;26 (April) Prophylaxis and AIDS-Related OIs For the clinician, however, this last effect may be the most important, because the clinical presentation of an opportunistic infection in a patient receiving targeted prophylaxis may not resemble the opportunistic infection in a patient not receiving prophylaxis. In addition, potent protase-inhibitorcontaining antiviral regimens also may fundamentally alter the presentation and natural history of OIs [7], further complicating diagnosis. I therefore will review reports describing qualitative changes in the presentation of common opportunistic infections in persons whose targeted prophylaxis fails. I will exclude failures of secondary therapy, since the diagnostic dilemma facing the clinician in such a setting is far less acute. Recognition of the potentially attenuating effects of failed prophylaxis is essential for clinicians caring for HIV-infected patients in the years ahead. Well-Described Atypical Presentations Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia In the absence of prophylaxis, PCP in patients with HIV infection typically presents as an indolent illness with constitutional as well as respiratory symptoms that may extend 1 month or longer. Diffuse bilateral interstitial infiltrates, hypoxemia, and an elevated lactic dehydrogenase level further suggest the disease. The diagnosis can readily be made by examination of an induced sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage specimen. Currently, there are three prophylactic agents commonly used to prevent PCP among patients with AIDS: aerosol pentamidine, dapsone, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Because none of the three is completely effective and because PCP is a common illness, ‘‘breakthrough’’ cases are encountered relatively often. In many circumstances, the clinical presentation and approach to diagnosis have been altered by the failed prophylactic regimen. Aerosol pentamidine. Numerous reports have described the atypical features that may be encountered when a patient receiving aerosol pentamidine develops PCP [8]. Features such as upper-lobe disease (in 38% of aerosol pentamidine recipients vs. 7% of those not receiving it) [8], pneumothorax [9], lower yields from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and other respiratory specimens (100% vs. 62%) [8], fever of unknown origin [10], and (possibly) extrapulmonary pneumocystosis [11] have been described. Thus, the radiologic appearance of and diagnostic approach to PCP are substantially altered by use of aerosol pentamidine. Dapsone. Unlike aerosol pentamidine, the clinical features of failed dapsone prophylaxis are not well-characterized. A report comparing PCP developing in patients receiving aerosol pentamidine vs. those receiving dapsone found similar clinical presentations, including respiratory complaints and chest radiographic features [12]. In addition, the sensitivity of sputum / 9c4a$$ap07 03-12-98 08:31:23 807 induction and BAL was similar (60% – 70%). Another report suggested that chest radiographic features may be atypical and may include lobar as well as nondiffuse bilateral changes [13]. A recent report of cutaneous pneumocystosis documented the potential for extrapulmonary pneumocystosis in persons whose dapsone therapy fails [14]. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The clinical characteristics of PCP among patients whose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis fails have not been described. Toxoplasmosis Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is recommended as prophylaxis for both PCP and toxoplasmosis [3], and it decreases rates of bacterial sinopulmonary disease as well. One report from France described breakthrough toxoplasmosis in two men receiving trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis [15]. Both had low CD4 cell counts and protracted fever. Extensive workup included multiple blood cultures and radiographic examinations, as well as CT scans of the brain. All tests were negative. Eventually, PCR and blood cultures demonstrated T. gondii. The diagnosis was verified by a clinical response to targeted antitoxoplasmosis therapy (clindamycin with pyrimethamine). Thus, toxoplasmosis in these patients receiving prophylaxis presented not as a classic brain abscess but rather as a fever of unknown origin associated with parasitemia. Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) Three agents are approved for prophylaxis against disseminated MAC infection: rifabutin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin. Even with optimal prophylaxis, however, breakthrough occurs in 3% – 12% of patients, depending on the regimen used. In a large series, patients whose rifabutin prophylaxis failed were found to have reduced fever and fatigue, higher hemoglobin levels, lower alkaline phosphatase levels, and an improved Karnofsky score, when compared with placebo-control patients who developed MAC infection [16]. No change between the groups was seen with regard to signs such as weight loss, night sweats, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. In another study that compared rifabutin, azithromycin, and combination rifabutin/azithromycin, ‘‘typical’’ disseminated MAC infection was seen in prophylaxis failures, including fever in 70% and anemia and weight loss in Ç50% [17]. Elevation of the alkaline phosphatase level, however, was seen in only 4% overall, a rate significantly lower than expected. In addition, while all azithromycin-treated patients with breakthrough MAC infection developed symptoms, symptoms were seen in only 56% of those receiving combination rifabutin/ azithromycin prophylaxis. This suggests that the most potent prophylactic regimen (with rifabutin/azithromycin) may have suppressed symptoms for many, even when the regimen ultimately failed. cidas UC: CID 808 Sepkowitz CID 1998;26 (April) Table 1. Effect of prophylaxis on the clinical presentation of opportunistic infections. Opportunistic infection Well-described effect Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia Toxoplasmosis MAC Herpes zoster No described effect Endemic fungi Tuberculosis CMV Prophylaxis Aerosol pentamidine Clinical effect Azithromycin Acyclovir Upper-lobe infiltrates [8], lower yield on BAL [8], pneumothorax [9], fever of unknown origin [10] Atypical chest radiograph (?) [13], extrapulmonary disease [14] Fever of unknown origin [15], extracranial disease [15] Less fever [16], fatigue [16], lower alkaline phosphatase level [16], higher Karnofsky score [16] With rifabutin (combination), fewer symptoms [17] Extradermatomal, hyperkeratotic verrucous papules [19] Oral azoles Isoniazid Ganciclovir No distinct differences described More AFB smear – negative disease (?) [23], less extrapulmonary disease (?) [23] Less-frequent colitis (?) [24] Dapsone Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole Rifabutin NOTE. AFB Å acid-fast bacilli; BAL Å bronchoalveolar lavage; CMV Å cytomegalovirus; MAC Å Mycobacterium avium complex. No clinical description of clarithromycin prophylaxis failures has been reported [18]. Varicella Zoster Virus Primary or secondary prophylaxis for both herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus with acyclovir is a relatively common practice. One report described the clinical appearance of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection in four patients who had received many months of chronic acyclovir prophylactic therapy [19]. The authors reported culture-proven acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection, presenting as atypical hyperkeratotic verrucous papules in a disseminated (nondermatomal) distribution. Atypical Presentations Not Well Described Deep-Seated Fungal Infections The oral azoles, including fluconazole and itraconazole, are widely used in the care of persons infected with HIV. Intermittent doses are often given for oral and/or vaginal thrush. In addition, odynophagia is often presumed to be due to C. albicans, and an azole is prescribed. This widespread use of oral azoles has resulted — serendipitously in many instances — in prophylaxis against various deep-seated fungal infections. Because the protection from these agents is incomplete even when dosing is sustained, and because the drug often is given only intermittently, breakthrough of deep-seated fungal infection may occur. A recently reported prospective study examined rates of histoplasmosis among patients in Kansas City, Missouri, an area of endemicity [20]. Investigators found 5 breakthrough cases in persons receiving azoles (4, fluconazole; 1, ketoconazole) among 304 patients followed for 2.5 years. No clinical descrip- / 9c4a$$ap07 03-12-98 08:31:23 tion of the breakthrough cases was given. Cryptococcosis similarly has occurred among patients receiving fluconazole in various trials. No clinical descriptions have been given, and investigators have tended to ascribe development of disease with individual-patient noncompliance [21, 22]. Tuberculosis Little has been written about the clinical characteristics of tuberculosis in patients whose isoniazid prophylaxis fails, although the microbiological consequences — namely, the emergence of resistance — have been much discussed. In a recent report from Nairobi, 48 cases of tuberculosis developed among 684 HIV-infected persons randomized to receive isoniazid or placebo (25 developed in the isoniazid arm, vs. 23 in the placebo arm) [23]. Patients receiving isoniazid had higher rates of smear-negative, culture-positive disease than did those receiving placebo, but the trend was not statistically significant (10/25 vs. 5/23; P Å .29). Rates of extrapulmonary disease were higher in the placebo group, but this also failed to reach statistical significance (1/25 vs. 5/23; P Å .15). These trends possibly suggest a more attenuated clinical presentation in those receiving (and failing to improve with) isoniazid therapy, but they are far too preliminary to allow firm conclusions to be drawn. Cytomegalovirus Oral ganciclovir has been shown to decrease the rates of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with advanced AIDS [24] by Ç50%. In the largest published report, both breakthrough retinitis and colitis were seen, although the rate of colitis may have been lower among those receiving ganciclovir. No additional description of clinical differences was reported [24]. cidas UC: CID CID 1998;26 (April) Prophylaxis and AIDS-Related OIs Conclusion Routine use of prophylaxis against specific opportunistic infections has had a significant impact on the trends in opportunistic infections [25] as well as upon overall patient mortality [7]. A series of landmark articles over the past decade have served to define our current approach regarding when and how to deliver optimal prophylaxis for opportunistic infections. The main focus of these reports has been to determine the effectiveness of a given strategy, usually expressed as a reduction in cases/rates compared to rates among patients receiving placebo. In addition, because of growing concern that prophylaxis might contribute to an increase in drug resistance, some prophylaxis studies, particularly those involving MAC infection, have also reported on the influence of the study regimen upon the susceptibility profile in breakthrough cases. The qualitative effect of failed prophylaxis on the clinical presentation of opportunistic infections is less well characterized. The attenuating effect of failed prophylaxis, however, wherein a specific disease is only partially prevented, has changed the clinical presentation of many AIDS-related opportunistic infections. As this review demonstrates, the clinical presentation of four common opportunistic infections — PCP, MAC, toxoplasmosis, and varicella-zoster virus — may be altered significantly in persons receiving prophylaxis, while data are incomplete for other infections, such as deep-seated fungal infections, tuberculosis, and cytomegalovirus (table 1). Promising advances in prophylaxis for opportunistic infections [2, 3] and in antiretroviral therapy [26, 27] have combined to improve greatly the quality and duration of life of persons infected with HIV [28]. With these advances, however, have come a new set of challenges for the clinician and the patient alike [7]. Attention must now be paid to the subtle changes in the clinical presentation and expected natural history of the opportunistic conditions brought about by these interventions, because, despite these improvements, opportunistic infections will continue to occur. And with each opportunistic infection, however atypically it may present, will come significant patient morbidity and mortality. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. References 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Atlanta: CDC, 1996. 2. Kaplan JE, Masur H, Holmes KK, et al. USPHS/IDSA guidelines for the prevention of opportunistic infections in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: an overview. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21(suppl 1):S12 – 31. 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997 USPHS/IDSA guidelines for the prevention of opportunistic infections in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. MMWR 1997; 46(RR-12):1 – 46. 4. Moore RD, Keruly JC, Chiasson RE. Effectiveness of combination antiretroviral therapy in clinical practice [abstract I-176] In: Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents / 9c4a$$ap07 03-12-98 08:31:23 20. 21. 22. 809 and Chemotherapy (Toronto). Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1997. Mouton Y, Alfandari S, Valette M, et al. Impact of protease-inhibitors on AIDS-defining events and hospitalizations in 10 French AIDS reference centres. AIDS 1997; 11:F101 – 5. Mars ME, Loi S, Suzan V, Gallais H. Protease inhibitors lead to a change of infectious diseases unit activity [abstract 203]. In: Programs and abstracts of the 4th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Washington, DC: IDSA Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health. 1997. Sepkowitz KA. The effect of HAART on the natural history of AIDSrelated opportunistic conditions. Lancet 1998; 351:228 – 30. Jules-Elysee KM, Stover DE, Zaman MB, Bernard EM, White DA. Aerosolized pentamidine: effect on diagnosis and presentation of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 1990; 112:750 – 7. Sepkowitz KA, Telzak EE, Gold JWM, et al. Pneumothorax in AIDS. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:455 – 9. Sepkowitz KA, Telzak EE, Carrow M, Armstrong D. Fever among outpatients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:1909 – 12. Telzak EE, Cote RJ, Gold JW, Campbell SW, Armstrong D. Extrapulmonary Pneumocystis carinii infections. Rev Infect Dis 1990; 12: 380 – 6. Torres RA, Barr M, Thorn M, et al. Randomized trial of dapsone and aerosolized pentamidine for the prophylaxis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and toxoplasmic encephalitis. Am J Med 1993; 95: 573 – 83. Chiliade P, Kwan R, Sharp V. Atypical presentations of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients receiving dapsone prophylaxis [abstract PoB 3305]. In: Program and abstracts of the 7th International AIDS Conference, 22 – 24 July 1992, Amsterdam. 1992. Bundow DL, Aboulafia DM. Skin involvement with Pneumocystis despite dapsone prophylaxis: a rare cause of skin nodules in a patient with AIDS. Am J Med Sci 1997; 313:182 – 6. Zylberberg H, Robert F, Le Gal FA, Dupouy-Camet J, Zylberberg L, Viard JP. Prolonged isolated fever due to extracerebral toxoplasmosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus who are receiving trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21:681 – 2. Nightingale SD, Cameron DW, Gordin FM, et al. Two controlled trials of rifabutin prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex infections in AIDS. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:828 – 33. Havlir DV, Dube MP, Sattler FR, et al. Prophylaxis against disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex with weekly azithromycin, daily rifabutin, or both. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:392 – 8. Pierce M, Crampton H, Henry D, et al. A randomized trial of clarithromycin as prophylaxis against disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infections in patients with advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:384 – 91. Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med 1990; 112:187 – 91. McKinsey DS, Spiegel RA, Hutwagner L, et al. Prospective study of histoplasmosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: incidence, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:1195–203. Powderly WG, Finkelstein D, Feinberg J, et al. A randomized trial comparing fluconazole with clotrimazole troches for the prevention of fungal infections in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. NIAID AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 700 – 5. Nightingale SD, Cal SX, Peterson DM, et al. Primary prophylaxis with fluconazole against systemic fungal infections in HIV-positive patients. AIDS 1992; 6:191 – 4. cidas UC: CID 810 Sepkowitz 23. Hawken MP, Meme HK, Elliott LC, et al. Isoniazid preventative therapy for tuberculosis in HIV-1 infected adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS 1997; 11:875 – 82. 24. Spector SA, McKinley GF, Lalezari JP, et al. Oral ganciclovir for the prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in persons with AIDS. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1491 – 7. 25. Hoover DR, Saah AJ, Bacellar H, et al. Clinical manifestations of AIDS in the era of pneumocystis prophylaxis. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:1922 – 6. / 9c4a$$ap07 03-12-98 08:31:23 CID 1998;26 (April) 26. Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:725 – 33. 27. Gulick RM, Mellors JW, Havlir D, et al. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 1997;337:734–9. 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: trends in AIDS incidence. MMWR 1997; 46:165 – 73. cidas UC: CID