* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chilling Inquiry for Moapa - University of Nevada Cooperative

Survey

Document related concepts

Historia Plantarum (Theophrastus) wikipedia , lookup

Ornamental bulbous plant wikipedia , lookup

Cultivated plant taxonomy wikipedia , lookup

History of botany wikipedia , lookup

Flowering plant wikipedia , lookup

Plant defense against herbivory wikipedia , lookup

Venus flytrap wikipedia , lookup

Plant use of endophytic fungi in defense wikipedia , lookup

Plant evolutionary developmental biology wikipedia , lookup

Plant physiology wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of plant morphology wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

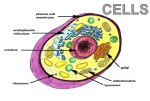

Chilling Inquiry for Moapa When the weather in winter becomes unusually cold, even snowy, most of the outdoor plants we care for so tenderly become miserable. In the case of many vegetables, a mere few hours below freezing will turn them into a forlorn mush. This is certainly an unwelcome sight, but at least the blackened plants are well on their way to being compost – which may only be scant comfort to the gardener. More surprising is that so many desert and desert-adapted plants do not die, but can survive until temperatures drop considerably below the freezing point, while others in the garden will suffer once it is below about 40°F. When a plant is damaged in cold, but not freezing, conditions, it is called “chilling injury.” Leaves will not necessarily die, but will turn colors that could be mistaken for a nutritional deficiency. There are good reasons why Mojave natives can live despite the environment. Desert plants evolved in areas where temperatures only rarely become extremely cold, but since it does happen occasionally, they have developed strategies for survival. Some of these are obvious, such as tree leaves turning color, and eventually dropping off as the autumn progresses, or grasses that die back, only to begin growing again with warmer conditions. Freeze damage left limp, brown leaves on this broccoli plant Some survival means are less apparent. All life is composed of cells. This includes everything that is alive: humans, trees, lizards, beetles and bacteria. The cells are certainly different, but they have many similarities, enough to indicate just how much life is the same. Plant cells are generally boxy shaped, with a large area within its walls. This area is a “vacuole,” but one should not confuse it with the word “vacuum” from which it is derived. Older cells have larger vacuoles. In many pictures, this organelle appears empty. Almost all cells – plant, animal, fungi – have vacuoles, but in plants it can take up a large area. Once there was a misconception that the large area had no role except to hold the cell rigid. While that is one of its roles, it is certainly not the only one. The vacuole is filled with several compounds, essential salts and nutrients. These are involved in the acid balance inside the plant. Healthy vacuoles also help to balance water between the plant and its environment; when the compounds within them become too concentrated, the plant shows signs of needing water. When it comes to cold weather, the salts within the cells can act much like adding road salt to an icy street. The salt causes the freezing point of water to become lower, and roads become less slick as the ice melts. Many of the solutions within plant cells have the same general function as road salt. In fact, many plants do not begin to freeze until temperatures and the cell contents are 28° or lower! This allows them to live even when it seems unlikely. Vegetables such as cabbage and kale can display some tolerance for cold, and will live even with some chilling. Many people claim chilling actually improves the flavor. Dr. Angela O'Callaghan is the Social Horticulture Specialist for University of Nevada Cooperative Extension. Contact [email protected] or 702-257-5581.