* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms Of Multiple

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

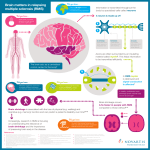

Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms Of Multiple Sclerosis Efforts to Pinpoint the Beginning of Disease May Yield Clues to Treatment Susan Worley A fter more than a century of impressive research, multiple sclerosis (MS)—a complex inflammatory, demyelinating neurodegenerative disorder—continues to have no known cause and no known cure. Important achievements in recent decades have included the development of more than a dozen disease-modifying treatments (Figure 1) for patients with relapsing and remitting forms of MS (RRMS).1 These drugs have been proven to reduce disability and likely delay progression in patients with RRMS; however, because the most effective among them pose risks for serious adverse events, the search for more tolerable agents for RRMS continues. Meanwhile, despite a lack of head-to-head clinical trials, efforts to establish a rational ordering of current treatments have led to early-stage treatment algorithms and efficacy rankings.2 RRMS, which is characterized by episodic inflammatory attacks on the central nervous system (CNS) and followed by spontaneous recovery of varying degrees, represents only one of several recognized categories of the disease.3 It is estimated that approximately 10% of patients have a primary progressive form of MS (PPMS), characterized by a gradual, irreversible progression of clinical disability, and more than 50% of patients who present with RRMS will eventually transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS). Drugs used to treat RRMS have so far demonstrated little efficacy in the treatment of progressive MS and are not currently approved to treat PPMS or SPMS. The absence of treatments for progressive disease has become an increasingly important focus of an international community of researchers. “A treatment for progressive MS is unquestionably the most important unmet need today, in part because progressive disease is the most significant source of disability,” says Philip De Jager, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “ Recently MS organizations around the world have launched a collaborative effort to tackle progressive MS, which will likely lead to some breakthroughs. Genetic studies and other research have taught us that if we join together rather than compete with one another on big questions such as this one, we stand a chance of being successful. We are at the point now where small studies of progressive disease led by individual investigators are unlikely to provide us with an answer.” Some of the current research on progressive disease involves delving deeper into its biology and pathophysiology. Homing in on the elusive beginnings of the disease, investigators believe, Susan Worley is a freelance medical writer who resides in Pennsylvania. Figure 1 Timeline of Approvals of Major MS Medications1 IFNB-1b (Betaseron) IFNB-1a (Avonex) Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) IFNB-1a (Rebif) Natalizumab (Tysabri) Teriflunomide (Aubagio) Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) Compound timeline Dalfampridine (Ampyra) FDA approval Fingolimod (Gilenya) Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) IFNB-1a (Plegridy) 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 This timeline shows milestones in the development of 12 available MS treatments, all of which are disease-modifying except for dalfampridine (Ampyra). It begins with the first patient visit of the oldest clinical trial, provides the FDA approval date, and ends with the last patient visit of the most recently completed and published clinical trial. It includes FDA-approved compounds and completed phase 2 and 3 trials, but it excludes unapproved compounds, ongoing trials, pilot studies, and phase 4 trials. 584 P&T ® • September 2015 • Vol. 40 No. 9 Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms of Multiple Sclerosis may provide insight into causes and potential treatments for all forms of MS. “We are basically at an inflection point in terms of understanding the onset of the disease,” Dr. De Jager says. “As with Alzheimer’s disease, MS develops over many years before symptoms appear, and so far we have not had an opportunity to observe the transition from health to MS; we’ve only observed patients already diagnosed with the disease. However, we now have detailed maps of the genes involved in the onset of MS, and we are on the road to discovering others. We also are zeroing in on environmental risk factors. As we gain a greater understanding of the biology that leads to MS, we eventually will be able to investigate primary prevention—strategies that will prevent the disease from starting in the first place.” of natalizumab has attested to a major role of the immune system; whether this represents ‘autoimmunity’ or ‘immunity to an infectious agent’ or both remains an enigma. We need to remain humble until we understand what causes the disease, and until we can cure it.” To arrive at a better characterization of the disease and identify opportunities for earlier treatment, more MS researchers are engaging in or proposing prospective studies that allow a closer examination of disease trajectories over time. One such study, led by Dr. De Jager and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), including Dr. Daniel Reich (see Frontiers of MS Imaging later in this article), is designed to examine the transition from health to MS by following a unique cohort of first-degree relatives of individuals with MS.6 The Genes and Genes and Environment: the Environment in MS (GEMS) study, which The Search for a Trigger was launched in 2011, has enrolled nearly 3,000 The complex pathophysiology of MS, which individuals who have provided detailed family Philip De Jager, MD, PhD is not yet completely understood, begins with and medical histories and saliva samples for neural inflammation that leads to the destruction of myelin in extraction of DNA. Participants commit to completing periodic the brain and spinal cord of patients. Inflammation of the brain questionnaires—and, in some cases, undergoing imaging and endothelium compromises the blood–brain barrier, allowing the other testing—over a period of 20 years. entry of immune cells into the brain. The mechanism of action Building on the work of previously conducted genome-wide for natalizumab (Tysabri, Biogen) (Figure 2), which is widely association studies and published studies of environmental considered the most effective treatment for MS, has provided risk factors, Dr. De Jager and colleagues developed a risk researchers with greater insight into the disease.4,5 While algorithm that is used to generate a weighted Genetic and some experts are inclined to think of MS as an autoimmune Environment Risk Score (GERS) for each subject. The study’s disorder, others are willing only to recognize an autoimmune risk algorithm can be updated to incorporate new risk factors component, and they remain in search of a “triggering event” and significant relationships among risk factors as these are that may or may not have autoimmune features. confirmed. Selected patients with high risk scores undergo “It does appear that, at least what we call relapsing–remitting imaging and other testing, generating data that eventually disease, can be highly attenuated by inhibiting the entry of the should enable investigators to map the intricate sequence of events that leads to MS. immune system into the brain,” says Lawrence Steinman, MD, Professor of Neurology at Stanford University. “The success “First-degree relatives of people with MS are an impor- Figure 2 Natalizumab blocks lymphocyte entry into central nervous system: (A) Alpha-4 integrin binds to vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) and to osteopontin (not depicted) on inflamed brain endothelium. This interaction gives lymphocytes access to the central nervous system. The presence of immune cells in the brain is a prominent feature of MS. (B) Natalizumab, a humanized antibody to alpha-4 integrin, blocks binding of lymphocytes to VCAM and osteopontin on inflamed brain endothelium, thereby preventing lymphocyte entry into the central nervous system. ©2012 Steinman. The Journal of Cell Biology.5 199:413–416. doi: 0.1083/jcb.201207175 Vol. 40 No. 9 • September 2015 • P&T 585 ® Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms of Multiple Sclerosis tant population because their risk for developing the disease is approximately 30 times greater than that of the general population,” Dr. De Jager says. “However, the absolute risk for each of these individuals is still rather small—only 2% to 3% will develop MS over their lifetime. By examining not only genetic risk factors but also environmental risk factors, such as a history of smoking or mononucleosis, our risk score seeks to identify the members of this population who are at greatest risk for developing the disease. We also expect to discover critical relationships among risk factors over time.” According to Dr. De Jager, plans are under way to expand the study to sites in more countries with the intention of making GEMS an international resource and eventually a platform for clinical trials that focus on primary prevention. As the study continues, members of the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium and other researchers continue to identify new gene variants that may play a role in MS.7 A deeper exploration of environmental factors, including immune responses to the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)8 and the influence of gender,9,10 also continue to yield valuable information about the disease. These are distinctly different from the nonspecific white-matter changes or bright spots that are seen in the majority of cases by neurologists, which are not consistent with MS.” More recently, Dr. Okuda and colleagues reported on data from 451 individuals in five countries who were retrospectively identified as having MRI anomalies suggestive of demyelinating disease.12 After following these individuals for five years, the authors identified risk factors—such as age (younger than 37 years), male gender, spinal cord involvement, and combinations of these—that were the most meaningful predictors of eventual symptom onset. Data from this study also identified a presymptomatic phase in individuals who went on to fulfill criteria for PPMS. An examination of clinical outcomes enabled investigators to identify characteristics that separated individuals who developed RRMS from those who developed progressive disease. Characteristics of the group with PPMS included a more advanced age range, a tendency to have an abnormal cerebral spinal fluid profile, a longer period of time to first clinical event, and a much higher lesion load within the spinal cord. To date, Dr. Okuda and colleagues have collected data on more than 14 RIS: The Value of Incidental Findings individuals with RIS who went on to develop progressive disease. Among individuals already diagnosed with MS, it has been estimated that approximately “One of our goals is to determine whether we Darin T. Okuda, MD 80% initially showed symptoms after the disease can use imaging early on in the disease course, had already been present for a decade or longer.4 This estimate prior to the emergence of symptoms, to forecast what clinical has long posed an intriguing question to researchers in the subtype of MS an individual will ultimately have. Although we field—among them, the lead investigator of another unique currently do not have any approved therapies for progressive prospective study of patients with MS. disease, we hope to determine whether we can intervene in “Figures representing the estimated incidence of MS and some way to prevent disability in patients on a progressive the estimated number of patients who are diagnosed each year trajectory,” Dr. Okuda says. have remained relatively stable during the past few years,” Dr. Okuda, members of the Radiologically Isolated Syndrome says Darin T. Okuda, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology Consortium (RISC), and colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern have formed a strategic research alliance with at the University of Texas Southwestern. “So an important question is: How many people do we think are unknowingly in Biogen to investigate, in a separate study, whether treatment has some early stage of the disease? Unless we screen the general the potential to delay the emergence of symptoms in individuals with RIS. This year, the alliance will launch ARISE, the first population, which is not currently feasible, or until we discover novel methods of identifying these individuals, we don’t really randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the U.S. to examine the know the prevalence of undiagnosed disease. However, we efficacy of dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera, Biogen) in extending can learn a great deal from MRI anomalies that are suggestive the time to a first neurological symptom associated with CNS of MS, and that are found incidentally during evaluations for demyelination.13 According to Dr. Okuda, the trial, which will symptoms unrelated to demyelinating disease.” involve approximately 200 subjects who fulfill RIS criteria at In 2009, Dr. Okuda and colleagues published findings from more than 20 sites in the U.S., is not seeking a new indication for the drug but rather the answer to scientific questions. a study of 44 asymptomatic patients with abnormalities on MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) that were discovered Dimethyl fumarate received FDA approval in 2013 for the treatment of patients with RRMS. In April 2015, noteworthy incidentally when these patients underwent MRI evaluation post-hoc analyses supporting its efficacy in specific types of for conditions such as head injury or migraine.11 The paper introduced the term radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS), patients were presented at the annual meeting of the American a presymptomatic category of MS, and presented formal criAcademy of Neurology (AAN).14,15 teria to improve diagnostic specificity and ensure accurate classification. Frontiers of MS Imaging “RIS only applies to structural radiologic anomalies that are MRI is an indispensable tool for monitoring MS, which until highly typical for demyelinating plaques,” Dr. Okuda says. now has largely involved tracking the presence of focal, demy“These lesions on imaging are not only of a specific size, elinated white-matter lesions—widely recognized pathological containing key morphological characteristics, but also are hallmarks of the disease. However, experts have long been located in specific areas within the central nervous system. aware that current imaging techniques relay only a partial 586 P&T • ® September 2015 • Vol. 40 No. 9 Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms of Multiple Sclerosis story: The number and volume of white-matter lesions do not that are expected to accelerate lesion recovery. In 2015, this correlate strongly with clinical manifestations of MS. An MRI method of assessing treatment efficacy will be used for the series may, for example, suggest extensive disease activity in a first time in early-stage testing of guanabenz (see Research Highlights below). patient who reports relatively mild symptoms. This imperfect correlation, known in the field as the clinical/ “If successful, our new trial design will allow radiological paradox, is a persistent source of the early testing of agents that might protect frustration for clinicians and patients. brain tissue, or promote its repair, to be conducted more quickly and with fewer patients, The degree to which MRI can track the compared with current paradigms,” Dr. Reich efficacy of treatments is also limited, in part because it is often impossible to distinguish says. “This should allow the early testing of between the efficacy of a drug and the spontamore agents at a lower cost, hopefully hastenneous remission of disease. ing the day when such treatments will reach our patients.” As a result, a major goal in imaging is to identify previously uncaptured or poorly captured processes in new regions of the brain and spinal Current Clinical Challenges cord that may provide relevant information Despite a wide range of treatment options for about disease activity. In 2014, progress toward patients with RRMS, clinicians face significant this goal was reflected in published reports of challenges in their efforts to tailor use of these Daniel Reich, MD, PhD significant relationships between gray-matter therapies to individuals. While experts agree abnormalities and disability in RRMS16,17 and in that early identification of the most effective SPMS.18 More recently, researchers reported success in using drug for each patient with MS is critical, pharmacogenetic a novel technique to capture leptomeningeal inflammation in information that might help guide treatment selection is lacking. individuals with MS,19 a process previously detected during Utilization management programs used by some insurers and autopsies and biopsies but never before captured in vivo. Now the need to observe risk-management strategies for many on the road to being validated as a new, noninvasive marker of medications also can complicate the decision-making process. inflammation, imaging of this pathology may eventually be used Lily Jung Henson, MD, a fellow of the American Academy to test treatments designed to reduce this inflammation and of Neurology and Chief of Neurology for the Piedmont Health may point to a new avenue of investigation for progressive MS. System in Atlanta, says that although natalizumab is widely “This marker likely can be made more sensitive,” says Daniel regarded as the most effective treatment for MS, it is not Reich, MD, PhD, Chief of the Translational Neuroradiology commonly used as first-line therapy for a variety of reasons. Unit at NINDS and lead investigator of this study. “And further “Natalizumab tends to be used as first-line therapy primarily investigation may help us discover other similar and perhaps in patients with very aggressive disease, in situations where more useful markers. Once we find these, we neurologists believe that if we don’t slow down can ask questions about the disease such as: the disease quickly, the patient may end up When does meningeal inflammation start? How having a lot of damage,” Dr. Jung Henson says. does it accumulate over time? Does it respond “For most newly diagnosed patients, we tend to recommend either injectables or the orals. to current therapies or potential new therapies, and if so, can that help us better understand The injectables make sense for patients who are the clinical course of the disease? Perhaps more conservative in terms of their willingness most significantly, answers to these questions to tolerate risks of adverse events. Patients can may eventually improve our understanding of be reluctant to begin taking some of the oral progressive MS.” drugs initially because they are relatively new, Another critical goal in imaging is the estaband we are still gathering information about lishment of clear and widely agreed-upon their side effects. However, if a patient is very definitions of response to treatment. Even for needle-phobic, an oral medication may be a well-established treatments, such as interferon more reasonable choice.” Lily Jung Henson, MD therapy, experts continue to explore better While Dr. Jung Henson and many of her U.S. methods for separating responders from nonresponders during colleagues generally support an efficacy ranking of current clinical trials.20 treatments published this year by Ransohoff and colleagues,2 For newer categories of drugs, including tissue-protective utilization management or “step therapy” programs developed and putative remyelinating agents, there has been an absence by insurers frequently lead to delays in effective treatment. To of sensitive markers for documenting efficacy. A further comaddress this problem, the American Academy of Neurology plication is that most of these newer agents will be tested in published a position statement in February 2015 that urges appropriate access to treatment.22 patients concurrently receiving approved immunomodulatory therapies; however, Dr. Reich and colleagues reported this year “Not long ago,” Dr. Jung Henson says, “I wanted to prescribe on a unique measure of lesion recovery that addresses this natalizumab for a patient with very aggressive disease; however, problem.21 The documentation of changes to individual lesions her insurer insisted that we try an injectable and an oral agent over time, these researchers demonstrated, can be used as a first. I wasted about three months watching her go downhill while powerful outcome measure in proof-of-concept trials for agents she failed therapy. Although I predicted that she would indeed Vol. 40 No. 9 • September 2015 • P&T 587 ® Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms of Multiple Sclerosis Table 1 Emerging Treatments for Multiple Sclerosis Agent Manufacturer or sponsor Description / Mechanism of Action Indication Name of Trial Status Monoclonal antibody that modulates interleukin 2 signaling; given once monthly by SC injection RRMS DECIDE BLA filed in April 2015 Antibody that targets CD-20 and mediates destruction of B cells; given by IV infusion RRMS OPERA Phase 3 PPMS ORATORIO Phase 3 Orally administered sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor binder that prevents lymphocytes from exiting lymphatic tissue SPMS EXPAND Phase 3 Masitinib AB Science Orally administered tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets mast cells and macrophages, important cells for immunity, by inhibiting a limited number of kinases PPMS, SPMS Anti-LINGO-1 Biogen Monoclonal antibody (BIIB033) that significantly improved recovery of optic nerve latency in phase 2 RENEW study; given by IV infusion RRMS, SPMS SYNERGY Phase 2; results expected in 2016 Used to treat vascular disease; has immunomodulatory and neuroprotective properties; administered orally SPMS MS–TAT Phase 2 (phase 3 trial planned) Sphingosine 1-phosphate 1,5 receptor modulator (new version of fingolimod); administered orally RRMS Monoclonal antibody against CD-20 protein on B cells; administered orally RRMS CONCERTO Phase 3 PPMS ARPEGGIO Phase 2 Zinbryta (daclizumab high-yield process) Biogen/AbbVie Ocrelizumab Roche Siponimod (BAF312) Novartis Simvastatin Imperial College London (with funding from Moulton Foundation and others) RPC1063 Receptos, Inc. Laquinimod Teva Phenytoin NMSS, MSS, Novartis (unrestricted grant) Used to treat epilepsy; blocks passage of sodium into axons; administered orally Guanabenz acetate NINDS, MRF, University of Chicago Protects myelin-producing oligodendrocytes to reduce demyelination; administered orally Phase 2b/3 Phase 3 Phase 2 RRMS Phase 1 BLA = biologics license application; IV = intravenous; MRF = Myelin Repair Foundation; MSS = Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; NMSS = National Multiple Sclerosis Society; PPMS = primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS = relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis; SC = subcutaneous; SPMS = secondary progressive multiple sclerosis Additional information available at ClinicalTrials.gov fail, we had no choice but to follow this path. These situations are frustrating and wrong—particularly when we know that they may lead to irreversible damage. We can’t take a cookiecutter approach to treating patients, because disease activity and severity and response to treatment often vary considerably.” Dr. Jung Henson adds that clinicians also must consider patient lifestyles, dosing preferences, and tolerance for risk when making treatment decisions. Indeed, these important factors have prompted considerable research geared toward improving patient convenience23 and safety24 for currently approved treatments. Ascertaining a patient’s tolerance for risk is particularly important because the most effective treatments for RRMS tend to have less favorable risk–benefit ratios. For example, natalizumab25 (and, in a handful of recent cases, two other MS drugs26,27) have been associated with a risk for developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a rare but serious brain infection. Other drugs associated with potentially serious adverse events that require patient enrollment in risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) programs include fingolimod 588 P&T • ® September 2015 • Vol. 40 No. 9 (Gilenya, Novartis), which poses cardiovascular and other risks;28 and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada, Genzyme), which poses a range of risks associated with prolonged immunosuppression.29 As efforts to develop more tolerable agents for RRMS continue, risk-management strategies for currently approved drugs are expected to undergo further refinement.30 Research Highlights: New Uses for Old Drugs A growing number of agents currently under investigation for the treatment of MS (Table 1)— particularly for progressive forms of the disease—are drugs that have already been approved for use in other therapeutic areas. In the past, new indications for older drugs were frequently discovered by chance, but researchers are now taking a more systematic approach to repurposing drugs and to leveraging their wealth of safety profile and post-marketing data. Simvastatin, a well-known, relatively safe, and well-tolerated cholesterol-lowering drug, for example, showed promise in a phase 2 clinical trial for slowing the progression of MS.31 Phenytoin, commonly used to prevent epileptic seizures, is Researchers Expand Focus on Progressive Forms of Multiple Sclerosis undergoing testing as a neuroprotective drug and may be useful in treating acute optic neuritis; results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial were presented at the AAN annual meeting in April 2015.32 More recently the Myelin Repair Foundation (MRF), in collaboration with NINDS and researchers at the University of Chicago, announced the launch of a phase 1 study of guanabenz, an FDA-approved drug used to treat high blood pressure. Researchers funded by the MRF (which has since announced its shutdown, although this is not expected to affect the ongoing study) reported in March 2015 that guanabenz prevents the loss of myelin and reduces symptoms of MS in animal models.33 Phase 1 clinical studies are assessing the safety and tolerability of the drug at doses used to treat MS. As will likely be the case in trials of other new neuro protective agents, patients participating in the phase 1 clinical trial of guanabenz will also be receiving an FDA-approved anti-inflammatory treatment for RRMS. Since many experts believe that treatment of progressive MS ultimately will require a mix of anti-inflammatory, regenerative, and neuroprotective strategies,34 such trials may be seen as harbingers of a new era of combination treatment. “Combination therapies already are standard in the treatment of disorders such as cancer and HIV/AIDS,” says Tassie Collins, PhD, Vice President of Translational Medicine at the MRF, “but a combination treatment approach to MS has not been possible until now. Ideally, this new generation of MS drugs, which are designed to protect tissue or to restore damaged tissue, will be coupled with approved drugs that target the autoimmune response. Combination therapy makes sense—it’s important not only to halt further damage, but also to help damaged tissue heal.” REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Multiple Sclerosis Discovery Forum. Timeline of approved compounds in MS. 2015. Available at: http://www.msdiscovery.org/ msline. Accessed May 29, 2015. Ransohoff R, Hafler D, Lucchinetti C. Multiple sclerosis: a quiet revolution. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11(3):134–142. Lublin F, Reingold S, Cohen J, et al. Defining the course of multiple sclerosis. Neurol 2014;83(3):278–286. Steinman L. No quiet surrender: molecular guardians in multiple sclerosis brain. J Clin Invest 2015;125(4):1371–1378. Steinman L. The discovery of natalizumab, a potent therapeutic for multiple sclerosis. J Cell Biol 2012;199(3):413–416. Xia Z, Chibnik L, De Jager P. Genes and Environment in Multiple Sclerosis (GEMS) Study: leveraging electronic communication to enable a prospective study of individuals at risk of multiple sclerosis. Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. Abstract published in Neurol 2015;84(14 suppl):S38.007. Available at: http://www.neurology.org/content/84/14_Supplement/S38.007.short?rss=1#aff-1. Accessed May 28, 2015. Esposito F, Sorosina M, Ottoboni L, et al. A pharmacogenetic study implicates SLC9A9 in multiple sclerosis disease activity. Ann Neurol 2015 Apr 25. doi: 10.1002/ana.24429. Ramanathan M, Cerza N, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Humoral response to Epstein-Barr virus is associated with cortical pathology in patients with multiple sclerosis. Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. Abstract published in Neurol 2015;84(14 suppl):P5.236. Bove R, Healy BC, Secor E, et al. Patients report worse MS symptoms after menopause: findings from an online cohort. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015;4(1):18–24. 10. Bove R, Musallam A, Healy BC, et al. Low testosterone is associated with disability in men with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014;20(12):1584–1592. 11. Okuda DT, Mowry EM, Beheshtian A, et al. Incidental MRI anomalies suggestive of multiple sclerosis: the radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2009;72(9):800–805. 12. Okuda DT, Siva A, Kantarci O, et al. Radiologically isolated syndrome: 5-year risk for an initial clinical event. PLoS One 2014;9(3):e90509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090509. 13. Okuda D, Lebrun Frenay C, Siva A, et al. Multi-center, randomized, double-blinded assessment of dimethyl fumarate in extending the time to a first attack in radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) (ARISE Trial). Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. Abstract published in Neurol 2015;84(14 suppl):P7.207. 14. Bar-Or A, Hutchinson M, Gold R, et al. Long-term efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis according to prior therapy: integrated analysis of the DEFINE, CONFIRM, and ENDORSE studies. Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. Abstract published in Neurol 2015;84(14 suppl):P7.229. 15. Phillips J, Gold R, Giovannoni G, et al. Clinical efficacy of delayedrelease dimethyl fumarate in newly diagnosed relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients with highly active disease: an integrated analysis of the phase 3 DEFINE and CONFIRM studies. Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. Abstract published in Neurol 2015;84(14 suppl):P7.228. 16. Schlaeger R, Papinutto N, Panara V, et al Spinal cord gray matter atrophy correlates with multiple sclerosis disability. Ann Neurol 2014;76(4):568–580. 17. Malkki H. Multiple sclerosis: Spinal cord grey matter loss correlates with disability in MS. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10(10):546. 18. Kearney H, Schneider T, Yiannakas MC. Spinal cord grey matter abnormalities are associated with secondary progression and physical disability in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86(6):608–614. 19. Absinta M, Vuolo L, Rao A, et al. Gadolinium-based MRI characterization of leptomeningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2015 Apr 17. pii: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001587. [Epub ahead of print] 20. Prosperini L, Capobianco M, Giannì C. Identifying responders and nonresponders to interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis. Degenerative Neurological and Neuromuscular Disease 2014:4:75–84. 21. Reich D, White R, Cortese I, et al. Sample size calculations for short-term proof-of-concept studies of tissue protection and repair in multiple sclerosis lesions via conventional clinical imaging. Mult Scler 2015 Feb 6. pii: 1352458515569098. [Epub ahead of print] 22. American Academy of Neurology. Position statement: availability of disease modifying therapies (DMT) for treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. February 2015. Available at: https:// www.aan.com/uploadedFiles/Website_Library_Assets/Documents/6.Public_Policy/1.Stay_Informed/2.Position_Statements/ DiseaseModTheraMS_PosStatement.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2015. 23. Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, Arnold DL, et al. Pegylated interferon β-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (ADVANCE): a randomised, phase 3, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(7):657–665. 24. Zhovtis Ryerson L, Herbert J, Kister I, et al. Safety and efficacy of extended dose natalizumab in multiple sclerosis: an ongoing multicenter study. Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. Abstract published in Neurol 2015;84(14 suppl):P3.267. 25. Antoniol C, Stankoff B. Immunological markers for PML prediction in MS patients treated with natalizumab. Front Immunol 2015;5:668. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00668. 26. Rosenkranz T, Novas M, Terborg C. PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med 2015;372(15):1476–1478. 27. Food and Drug Administration. Gilenya (fingolimod): drug safety communication—FDA warns about cases of rare brain infection. continued on page 605 Vol. 40 No. 9 • September 2015 • P&T 589 ® MS Researchers Expand Focus continued from page 589 August 4, 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm457183.htm. Accessed August 14, 2015. 28. Ontaneda D, Hara-Cleaver C, Rudick RA, et al. Early tolerability and safety of fingolimod in clinical practice. J Neurol Sci 2012;323 (1–2):167–172. 29. Willis MD, Robertson NP. Alemtuzumab for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015;11:525–534. 30. Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, et al. Anti–JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 2014;76(6):802–812. 31. Chataway J, Schuerer N, Alsanousi A, et al. Effect of high-dose sim- vastatin on brain atrophy and disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-STAT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9936):2213–2221. 32. Kapoor R, Raftopoulos R, Hickman S, et al. Phenytoin is neuroprotective in acute optic neuritis: results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Presentation at American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, April 18–25, 2015, Washington, DC. 33. Way SW, Podojil JR, Clayton BL, et al. Pharmaceutical integrated stress response enhancement protects oligodendrocytes and provides a potential multiple sclerosis therapeutic. Nat Commun 2015 6:6532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7532. 34. Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14(2):183–193. n Vol. 40 No. 9 • September 2015 • P&T 605 ®