* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download lnrt /on ltny an I us tng /tÇn rout"nt

Direct democracy wikipedia , lookup

Thebes, Greece wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Liturgy (ancient Greece) wikipedia , lookup

Spartan army wikipedia , lookup

Second Persian invasion of Greece wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Eurymedon wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek warfare wikipedia , lookup

THE

BC

5OO-44O

WORLD:

GREEK

249

'who were anned with whips, would, driae au)oy anyottß

whn øpproarhcd. Aristides once intendcd to tax

Pawønias with thß and expostula.te with hirn, but he

pul on afrown, told, Aristidns that he was occupicd, an'd'

refisedto listento him.

After this thc gencrals and' ødmirals of the

ph.e Athenians'l object being to compensate themseh¡es

for their losses by rauagíng th.e territory ofthc hing of

Persia.

THuqyDtDEs, Peloponnesian

Greeh

Wa4 trans. by

R. Wennen, p. 66

expedition, especially thase of Chins, Sam,os an'd' Lesbos,

approachcd Aristidcs and, pressed hirn to øccept the

suprenle command, and, rally aroun'd him th,e alLies who

had,long wished to be quit of Sparta an'd' to transfer

thcir support to Athnns. Arßtides nld them' that he

regørded, their proposøls as both necessary an'd

jwt.

Greehs'l aims probably itælu.d¿d also thcir

d,etermination to protect those Greek' states whírh had'

alreød,y reuohedfrom Persia and, to liberate those still

Phe

PLUTARcH, Thc Rí:e and' Fall of Ath'ens, trans. by

l. scorr-KlLVERT,

pp. 134"-5

undnrPersianrule,,,

J. FINE,

(Un

lnrt /on dt'ny an I

/^6e

,ourcet

us

The

Arcicnt Greelr,p.333

tng

(Un

dntt / on lt'ny an I

a

How did Athens gain command of the I-,eague?

/.6e ,ources

o

Why were the Spartans unwilling to tølre the

leødership?

;

s Can you d,etect any d,ffiren'ces in the sources?

: How irnportant were the personalities of Aristides

and, Pausanías in the formation of the League?

The main reasons the Athenians became the leaders of a Greek alliance were:

o their kinship with the Ionian Greeks

o Spartan isolationism

o, Athens' naval strength and reputation after Salamis

o the role of individuals such as Pausanias and

Aristides.

The alliance is referred to by modern scholars as

the 'Delian League', but the Greeks themselves called

it the 'Athenians and their allies'. The term hegemon,

meaning leader of a group of states, was now applied

to the Athenians.

The purpose of the League

th,e lonians the oøth by whi'ch

they swore to haae thc samc ene¡ni,es and' the sam,e

fn nd* os the Athenians. h was in confi'rma,tion of this

oøth that they cast the hcauy pinces of iron into the sea.

ARtsrorLE, Constítutinnof Atherc, trans. by

K. von FRITZ & E. KAPP' pp.93-4

tng

What does Aristides say was the purpose of the

alliance?

:

Why were iron bars thrown into the sea?

s

How d,o the explanations of Thucyd'íd'es and Fine

dffir?

Membership of the League

siates joined the Delian League

at its outset. Chios, Lesbos and Samos were founding

members, as were most of the Ionian city-states in the'

It is uncertain which

northern Aegean and along the coast of Asia Minor'

Most of the states who joined ihe alliance were hoping

to be freed from the threat of Persian domination and

in trade with Athens. In 47817 BC

the Athenians invited all interested parties to a meetshared an interest

ing on the island of Delos.

(Un

lnrt /on ltny

/tÇn rout"nt

Look.

[Arßtidcs] aùninßtered, to

us

an

I

us

tng

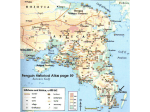

at Figure B.ll and' explain why Delos

was

chosen.

Other reasons Delos was chosen were:

o it had an excellent harbour

o it was a cult centre for Apollo (an important

god for

all Greeks) and a sacred site

o it

was politically insignificant and therefore

unlikely to challenge Athenian supremacy.

N

ul

o

T

(n

--l

a

MACEDONI,A

Propontis

l¿

¡-

lt

Eqal

r¡

PHRYGIA

n

CORCYRA

o

D

r\

U

o

,

g

LEUCAS

ADTOLIA

LYDIA

:*"il

I

¡

CEPHAtt#

zAcYNTHUSb

,

,3

W

IñE!!E

0

Members of the Delian League

t

50

t00

r50

¡ÞDELos

oMagnesia

/t

r

*-;ü'fy

,r"ufð

fu."r"ruo

t

¡

cos

û

It

&

200

kilotnetres

FIGURE 8. I f

¡

*"ro, Éd'

Members of the Peloponnesian League

Athenian colony

\w

-brENos

t,

n

The Delian and, p^t ^^^^-n.ìnn. Leagues

x

o

@

EPIRUS

o

CRETE

,*o*"o"o'

Sardes

THE

o

or phoros

The Delian League did not have a written constitution,

and our knowledge of its workings can only be gleaned

from the writings of Thucydides, Plutarch and

Aristotle or pseudo-Xenophon (the possible authors of

a work on the Athenian constitution).

To fund the alliance and to carry out the purposes

of the League, money and ships were required. This

ophoros',

and all member states

tríbute was called lhe

were expected to contribute.

BC

5OO-44O

that Thucydides confused

Organisation of the League

The tribute

\MORLD:

GREEK

251

it with figures for a much

later period. The amount of tribute received by Athens

between 450 and 436, when the membership of the

League was much higher than at the beginning: û€v€r

exceeded 460 talents. From inscriptions on the acropolis, it is known that Aegina (Athens'old enemy) paid

the largest amount of tribute: 30 talents. Abdera and

Byzantium paid 15 talents each year.

Constitution of the League

The League consisted of independent states who met

in congress to make their decisions. However, it is

clear that the alliance was unequal from the beginning

because:

o

At this time thn offrcials ktwwn os 'Hell.enic Treasurers'

were

fi,rst appointnd by the Ath'eniø¡u. These offiriøls

receiaed, thn tribuæ, whi,ch was th,e nnme giaen to thc

contributions in rnoncy. Thc original sumfixedfor thc

tribute was 400 tal,ents. Thc treasury of th,e lcøgtrc was

the leadership was Athenian

Athens had the largest fleet

o Athens was superior in resources.

How did this congress operate? There are two differing views on this.

r

atDelos...

TH uqyD¡ DE s, Peloponnesian War, trans. by

R. I¡VARNER, p.6ó

lThe Greelæl øpplicd to

AristiÅ,es and, øppoinæd

th.e

Athcnia

ns

þr

thc seruices

The ch.oire lay benteen either a unicømcral or a

bicø,mcral d¿cision-making struÆture. In a unicameral

structure euery member, irælud,ing the h,egemnn, has

only one uote in a single chamber---<t simplc majority

decid,ing policy. In a bicaiæral strut:ture thcre are two

chambers, consisting of th,e h,egeman in onc chamber

and. thc rest of th.e allies in thc other chømber. Ecwh

chamber is cotutitutinnnlly equal in power to earh othcr,

and, thcrefore a polfuy is only authorßed'whcn both

charnbers aote infauour. If oræ chamber opposes the

of

him to suruey thc aarinw

territories and thcir ret)enues, and' thcn tofin th'eir

contributioru accord,ing to earh metnber's worth an'd,

ability to pay . . . he drew up th.e list of ossessmcnts rwt

only with scrupulou ir*egrity and justine, but also in

such a way that all th.e states feh they had, been

appropriøtely and. søtßfannrily dcah with . . . The tan

which Aristidcs imposed ømnunted, to 460 talcr*s.

proposed

polity

rejected,,

In

reo,ch¿d by

lntt / on lt'ng an I

Q,/n

us

tny

/6e sour"et

;

:

What were the allies expected to contribute?

s

In what ways did Athens control the Iæaguefrom

Who assessed th.e tribute? Who collected it?

the outset?

You will note that there is a contradiction in the figures given by Thucydides and Plutarch. This has been

much debated by historians, and many different explanations have been put forward. The figure is too high

for the initial stages of the League and it is thought

a ma,jority aerdi,ct within the chamber.

T. BucKLEY , Aspects

PLUTARc.H, Th,e Rise and Fall of Athens, trans. by

l. Sqorr-KtLYERT, pp. 131{

(Un

ønd. passes ø ueto, th,en thc policy is

this strurture thc alli¿s' d,ecßinn wou'ld' be

of Greek Hisnry, p. 192

lntt / on dtng an I

us

tng

/6e sources

:

:

t

How

d,o

you think this council operated?

What aoice did eøch rnember haae?

How did Atl¿ens exert íts leadership?

fnternal development of the League

Because there was no written constitution the

Athenians could change the rules to suit themselves.

No provision was made for members to leave the

League. Over a period of time, more members preferred to pay tribute rather than consume resources

and manpower in building ships.

252

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

As the Persian threat diminished, the League mem-

bers resented having to make contributions when

there was no longer any need. In 469 BC the first rumblings of dissatisfaction became evident. Naxos

attempted to seeede from the League, but Athens

responded by using Delian forces under Kimon to

besiege Naxos and force it to submit. In 465 Thasos,

the greatest contributor of ships, expressed its resentment at Athenian inter{erence in its gold-mining operations. The Athenian fleet defeated the fleet of Thasos

in a naval battle. The city of Thasos was besieged in

46543 BC. The people of Thasos were defeated by

the Athenians, who pulled down the city walls. The

Thasians lost their ships and mining interests, and

agreed to pay tribute. The Athenians sent colonists to

nearby Thrace.

Over a period of time, Athens reduced the independent states in the League to subject status. In M7 BC

the island of Euboea took advantage of the troubled

Zot ltscussion

How d,o you think other rnembers of the League,

unhappy about the contribution of ships and, money,

might feel about Athens after its treatnlerut of Naxos

and, Thasos?

Benefits for the allies

Despite the dissatisfaction of some members, there

were benefits for the allies:

o

Athenian currency, weights and measures had to be

used on pain of punishment. Although this was a

harsh measure, it facilitated trade. The Piraeus with

facilities for unloading ships and storing grain,

relations between Athens and Sparta and revolted.

became the port of the empire. Aegean waters were

Euboea was reclaimed by Athens a year later. By 440

BC only Chios, Lesbos and Samos were independent

members but in 440-339 BC Samos revolted. Athen

Trad,e-Athens imposed a coinage decree on the

allies. The date of its imposition is debated by

scholars. The decree banned the use of any nonAthenian coins in the cities of the League.

safer for trade when the pirates of Scyros were

defeated and enslaved

in476BC.

o Protection-the strong fleet of the Delian

compelled Samos to submit once more.

League

protected members against the renewed threat of

the Persians.

o

Gouernmenr-Athens strongly encouraged members

to establish democracies as their form of govern. . . No.ros left the League

ment. The allies had access to Athenian law courts.

and th¿ Athcnians mndc war

on th.e plore. Afier a sicge Naxos was forced, back to

allegiance. This was th.ertrú cose whcnthc original

corxtitutinn of thn Leøgue was broken and, øn øllicd city

lost its indcpen"dcrrce, and, th.e process was contimtcd, in

o Spoils-at the beginning of the League the allies

the coses of th,e other ølli,es as aøriaus circumstances

arose. Thn chinf reo.sons for th.ese reaolts were failures to

prod,ure thc right a,maunt of tribute or thc right numbers

of ships, and, somctimcs a refusal to prod.u.ce øny ships at

Disadvantages

all. For the Athenians i¡tsisted on obligations being

excrctly met, and, mnd.e th,emselaes unpopul,o,r by

bringing the seuerest pressure to bear on alli¿s whn were

tnt wed to mnking sorriftrces and did nat want to mak¿

th,ern, In other ways, too, thæ Athenians as rulers were ¡tn

longer populør as th,ey wed to be.

THUcyDrDEs, Pelnponncsian

We,r, trans. by

R. Wannen, p.67

Q/n dn.t /an

ú'ng

an

I

u stng

received booty from attacks on Persian territory

(e.g., the sale

ofslaves).

\

for the allies

o Loss of autonomy-the allies could not secede.

o Allies were unwilling to travel long distances to the

Athenian law courts.

o Payment

o

o

of tribute/ships-this continued even after

the Persian threat ended. (Later there was great

resentment when tribute was used by the Athenians

to beautify the city of Athens.)

The enforcement of the currency decree took away

the allies' right to mint their own coins.

The cleruchies (colonies) that were established by

the Athenians were resented by the allies because

they felt they had spies in their midst. Many of the

cleruchies also had garrisons of soldiers attached to

them.

/Âe sources

Benefits for Athens

;

;

How would, you describe Athens' rol,e in these euents?

a

What was the signfficance of these reuolts?

Why did these states reuoh?

. Power-Athens had access to, and control of, a

large and powerful alliance of wealthy states.

Sometimes this was used for the benefit of Athens

THE

5aO-44o

BC

253

BC (the exact date is not known). The Persians had

destruction of Thasos.

assembled a large fleet at the mouth of the Eurymedon

River in southern Asia Minor perhaps to launch an

attack on the Greek cities of the Asia Minor coastline

and the offshore islands. Kimon, with an allied fleet of

300 triremes, sailed to Eurymedon and won an

impressive victory against the Persians on land and

sea. The majority of the allies would have regarded

this success at Eurymedon as fulfilling the primary

purpose of the Delian League. As a result, more of the

received one-sixtieth of

total tribute as repayment for organising the

League. They received half of the booty collected

from the campaigns against the Persians. Sale of

slaves also gave them added revenue.

o Trøde-rhe Piraeus

became the main port of the

Aegean. The coinage decree forced the allies to

trade with Athens. Excess tribute aÍter M9 paid for

new docks, storehouses, harbour facilities and

buildings like the Corn Exchange. Cleruchies

o

WORLD:

rather than the League, as in the example of the

o Weahh-in 478 Athens

o

GREEK

established in conquered territory formed part of an

attempt to create a unified system of free trade.

Employmsn¡-n¿vaLl initiatives stimulated employment for rowers, shipbuilders, dock workers and

builders.

Cleruchies-when a state revolted from the League,

Athens usually established a cleruchy of Athenian

citizens to maintain a presence in the area. This

benefited Athens by ridding the city of its excess

population.

Zot lr'rturrr'on

Were there any disadaantages

(5)

Kimon followed this up by defeating some

Phoenician ships off the.coast of Cyprus. These victories were so decisive that the Persians took a number

of years to regain their strength. In areas from which

the Persians had been expelled, the Athenians established their own settlers.

(6) Kimon had by now established his reputation

as an incomrptible political leader. ln 465/4 BC, dur-

ing an unsuccessful attempt to colonise parts of

Thrace, Kimon was accused of comrption by his political opponents. Because of his great popularity at this

(7) In 459 BC the forces of the Delian

for Athens?

In the first few years of the Delian League the main

objectives were carried out by Kimon, son of

Miltiades, the hero of Marathon. Plutarch spoke of

Kimon as equalling Miltiades and Themistocles in

bravery and intelligence, and as oimmeasurably'

exceeding them in statesmanship.

)

than provide men and ships.

point, he was acquitted.

External policy of the League

(f

allies decided to make a payment of money rather

In 477 BC the exiled Spartan king Pausanias

in Byzantium and had cap-

set himself up as a tyrant

tured the town of Sestos. Kimon led an expeditionary

force to recapture these two cities.

(2) After successfully

completing this mission,

Kimon sailed to Eion on the Strymon River. This was

the most important Persian stronghold in Thrace, and

although the Persians greatly outnumbered the

Athenians, the Greeks were successful.

(3) The island of Scyros was inhabited by pirates.

These were expelled by Kimon's forces in 47413 BC.

Kimon established a cleruchy in this strategic posi-

tion. An interesting highlight of this expedition was

the discovery of fhe bones of the legendary Theseus

which were recovered and returned to Athens.

Plutarch comments that under Kimon the Athenians

carried the war into their enemies' country and won

new colonial teritory.

(4) Kimon's greatest military achievement was his

campaign at Eurymedon in Asia Minor in 469 or 466

League sup-

ported the Egyptians in their revolt against Persian

control. At first they met with some success, but by

454 the Persians regained control of Egypt and

destroyed the Greek forces.

(B) As a result of this disaster, the Phoenician fleet

was once more active in the Aegean, giving Athens the

excuse to move the treasury from Delos to Athens.

(9) There was a resurgence of Persian power in the

450s when the Persians actively tried to regain control

over the League allies in Asia Minor. The imposition

of the Erythrae Decree in 45312, which imposed a

democratic system of government and an Athenian

military garrison on the people of Erythrae, probably

indicates the hardline imperialistic stance taken by

the Athenians.

(lO) Kimon returned from exile in 45110 BC and

took up the command of the League forces. He died in

Cyprus in 449 fighting against the Persians.

(11) Historians believe that, in 449 BC, some form

of peace was made between the Athenians and

Persianso known as the

opeace

of Kallias'.

Changing relations with Sparta

This period, 459-444 BC, is sometimes called the

First Peloponnesian War by historians.

o

Kimon, the leader of the League forces, was a con-

servative politician and followed a pro-Spartan

policy. In 462 BC he convinced the Athenians to

aid the Spartans, who were trying to deal with a

254

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

revolt by their population of Messenian helots.

Kimon and the Athenian forces were humiliated

when the Spartans sent them away. The Spartans

had begun to fear Athenian success against the

control of Megara. Athens had lost its land empire

and had to be content with developing its maritime

empire. The defeat at Koronea persuaded Athens in

446 BC to make a peace treaty with Sparta known

Persians and the growth in Athenian power. Kimon

as the

was ostracised for his part in these events.

o Athens made alliances

with Argos and Thessal¡

Sparta's traditional enemies.

o Megara,

a strategically important member of the

Peloponnesian League, defected and joined the

Athenians.

o In 45918 BC Athens went to war against

her old

enemy, Aegina. Sparta did not suppot her allies at

this point, and in 457 A,egina surrendered, losing

its navy and becoming a tribute-paying subject of

Athens.

o

During the 450s, Athens gained a considerable

land empire in central Greece, consisting of

Boeotia, Phocis and Locris. This brought Athens

into opposition with the Spartans and the

o

Peloponnesian League. The Athenians, however,

had difficulty in maintaining their control over such

a wide area and in fighting on so many fronts. By

447, at the battle of Koronea, Athens had lost its

land empire and had to be content with developing

its maritime empire.

In 447 BC Athens went to war with Sparta at

Koronea in Boeotia. The Athenians were defeated

and their leader, Tolmides, was killed. As a result of

this, the cities of Euboea (Athenian subjects)

Thirty Years Peace.

The primary source for these complicated events is

Thucydides, who detailed Athens' rise to power in The

Peloporunesian War, Book L Thucydides refers to this

period of history as the opentecontøetiø' which means

the 'first fifty years', the period leading up to the

Peloponnesian War.

In Boeotía, the Athenians put ínto thcfield 1000 of their

own infantry and, some alli,ed dctachmnnts, in ffinsiue

ctction against th,ese tdrgets; Tolmidcs, Tolmaios' son,

was in cotnmand,. After capturing and, erulaaing

Chaeroneia, they began to withdraw, leauing a garrison

behind. On the mørch they were atkrclæd. at Koroneia by

the Boeotian exiles ... The Athenians utere d,efeated in

pitched, battle: some were killed; the rest were talæn

aliue. The whole of Boeotia wos then na.anted by

Athcru, undcr an agreettÊnt whereby th.ey got their øwn

men au)ay. Those of the Boeotiaru who had been in

exile, ww returned, home, and all th,e rest of Boeotia

re g aínc

d its

in dep en

derce.

It was rnt long after thß that Euboeø reuoltedfrom

Athetæ. Peri.cles had already crossed, ouer to Euboea

an Ath¿nian ørm,y wh,en h,e receiued, the neus that

uith

revolted, Sparta attacked Attica, and Athens lost

Popular eouræ

Council of 5O0

(Dikasteria)

(Boule)

50 members

Areopague

(Council of ex-archons)

9 archone

selected frorn the first

two economic classes

from each tribe

l0 generals

(strategoi)

I from

each tril¡e

Assembly

(Ekklesia)

Composed of all male

citizens over the age of lB

Anny

FTGURE 8.

l2

The structure of Athenian gouernment at the beginníng of the Sth century

THE

Megara had reuolted, that the Peloponnesiaru were

poised to inuod,e Atti.ca and that th,e Athenian

occupatian troops had been annihiløæd by thc

Megarians ... It was afier thß thøt th¿ Peloponræsians

mtnted. inn Atü,c territory, strihing at Eleusis and Thria

anÅ, d.estroying thn lønd ... Howeuer, they mndc rn

furthnr ad,uaræe and withÅrew homeuørds. Orx:e mnre

th.e Athenians crossed ouer to Euboea, with Perirles in

commnnì,. Thny gairæd control of the whnle tenitory,

and imposed, a settl,emcnt on all except Hestiaca; frorn

the lntter thcy droue all thc populatiory and, settl¿d thc

lønd. there th.emselues. Not long afier returningfrom

Euboea, thcy rutd.e a peoce treaty wi;th thc Spartøræ

and. theír allicsfor thirty years: Ath,ens surrend¿red

Nisaea, Pego,e, Troezen, and, Achaea, thefour

Peloponnesiøn positi,oru still in th.eir hønds.

THucyDrDEs ,'The Peloponræsia,n Wa4 cited in

A. FRtNclr,

Th¿ Athenian

Half Century, p. 66

9"rþr/Ânr ìnttes/z'Va/ion

Read, Thucyd,ides' account of these years

in

Boolt. I,

103-17, or consult textbooks such as N. G. L.

Hammond, The History of Greece to 322 BC;

V. Ehrenberg, From Solon to Socrates,' or J. V Fine,

The Ancient Greeks.

Zc/tt,t

cREEK

WORLD:

5OO-44O

BC

255

Modem scholar Christian Meier claims that by this

time the Delian League had become an Athenian

empire.

Thc Delian lcagtte had long possessed the trappings of

an empire, but at this point it clearly became an empire,

or, to use thc Greeh tenÌt, an arche, In the offi,cial

d,ocum,ents we euenfi.nd, a refereræe to the'Athcnians

and, th,ose ouer whotn thcy rule', The pea,ce treaty with

Sparta refl,ects thi"s, too-it spealts twt of a military

alliance against Persía but of two Greelt pou)er centers

facing

ea,ch oth¿r.

Relatinw within the Delian lzagun cøn

fromthn

speeches Thrcyd,idcs irælud,ed

be ded¡ned,

inhis hßtory

and, al,sofrom a number of inscriptiaræ, irælu.d,ing

tribuæ lists and aarious treati,es. In the speech.es, what is

rutst striking is the tyranni.cal power Athcns exercised,

u;er its allies, som,ething Periclcs anÅ other orators

pointed at with pri.d,e. Thny assert thøt th.efoundati,oru

of this power were laid,whcn Ath,ens, a.t thc reEtcst of its

allíns, assumed lcadership in the war agairæt Persia.

Th,e Athcnians hoÅ. kept the alliønce aliuefor three

re(ißons, th,e samc three

that mntiuate

m,ost

puterful

the Spartans, hod, only owi chnit:e, eithcr to rule by

might or to pu,t thnir own positinn in jeopardy.

c.

. ESSA

METER, .Arhcns, p. 358

lnølyse how Athens gained, and lost its larud empíre.

The League becomes the Athenian

etnpire

By 454 BC Athens had discontinued meetings of the

Delian League on the island of Delos. The treasury

had been removed for safekeeping to Athens after the

defeat of the Delian fleet in Egypt. By 450, owing to

the actions of Kimon and the forces of the Delian

League, the threat of Persian aggression had considerably diminished. Once an agreement had been made

between the Athenians and Persians, the initial justification for the League was removed. A peace treaty

POLITIqAL CHANGES IN

ATHENS

Overview of Kleisthenes' reforms

In the late 6th century the Athenian statesman

Kleisthenes made major changes to the Athenian system of govemment. The area of Athens and Attica had

previously been divided into four tribes. Government

with Persia was a sensible move. However, the

and public life were controlled by the aristocratic

families. Kleisthenes' reforms attempted to break this

stranglehold. The whole area of Attica was divided

into 139 demes (villages or local areas). Kleisthenes

Athenians sought to maintain their power and to preserve the League, arguing that the Persians would

strike again if the Greeks appeared weak.

Athens consolidated its dominance of the League.

By 440 BC most of the allies were subjects of Athens,

and the tribute paid into the Athenian treasury was

being used not only to maintain the fleet, but to

rebuild and beautify the city of Athens.

then organised ten new tribes, each consisting of several demes (about 14). The Council was enlarged from

400 to 500 members. The method of selection was by

lot-fifty members were chosen from each of the new

tribes. The Athenian assembl¡ or Ekklesia, acquired

wider powers to review and try cases. These measures

gave more power and greater opportunities to the citizens, and broke the inlluence ofthe aristocrats.

256

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

Major changes in Athenian democracy

from 5OO-45O BC

Athens was greatly affected by the Persian Wars and

the aftermath of those wars. Significant changes were

made to the internal government of Athens. The

changes that took place between 500 and 450 BC

were part of the democratisation process, bui they

must also be seen as responses to the Persian Wars

and as consequences of the growing imperialism of

Athens.

It is important to understand the inter-

relationship of the democratic changes with the events

of the 5th century.

The political changes that occured in this period

can rightly be seen as a tuming point in history. In the

first half of the Sth century Athens developed from a

land power to become the leading maritime state in

Greece. Simultaneously, Athens underwent major

political changes that revolutionised and transformed

the state from a moderate to a radical democracy.

Democracy was essentially a product of the 6th

century but it continued to develop in the Sth century.

By 508 BC, Athens had adopted the democratic

changes of Kleisthenes, but it would remain largely a

plutocracy for the next fifty years-the great statesmen would continue to be drawn from the ranks of the

wealthy.

Democracy then and no\,r

o Isonomia--equality under the law

o Demoltrøtiø-sovereign power of the people

century. Prior to this, the Athenians refer:red to their

government as oisonomia', meaning 'equality before

the law'. As Pericles observed, 'when it is a question

of settling private disputes, everyone is equal before

the law' (Thucydides, Peloponnesian Wør,II, 37). To

the Athenians, the word od,ernos', meaning 'the people',

could be used in a number of ways. Technically it

referred to all the Athenian citizens meeting in the

Bkklesia, and so conveyed the idea of 'the majority'.

The word was also used in an emotive and negative

sense to mean

othe

common people', the lower classes

or the poorer citizens.

Many Athenians in the sixth and fifth centuries

believed that govemment was best exercised by those

men who were well born-the wealthy land owners.

There were numerous terms for these men: 'the best

men' (aristoi), 'the well born' (eugeneis) and'the men

of note' (gnorimoi). Athens' obest men' seemed to fear

that the changes to the democracy would enable domination by the common people. The political contests of

this period were often polarised between the supporters of rhe d,emos and the supporters of 'the men of

note'. The conservative democrats believed in choos-

ing leaders from among their friends; the radical

democrats believed that the people should rule.

Problems with sources

It is important to note that sources on the transformation of Athenian democracy are limited. There is no

one source that deals with all of the changes in a

chronological sequence; therefore, information has to

has a positive connotation. The Greek word 'dem,okratia', meaning the osovereign power of the people', was

be gleaned from scraps of evidence in a variety of

places. Because ofthe lack ofevidence it is difficult'to

supply accurate dates for many of the changes that

occurred and to name the people responsible for intro-

not used to describe democracy until late in the Sth

ducing these changes.

In modern society, the word odemocracy' generally

ffi*

Some of the Archon's functions transferred to the strategos

Battle of Marathon shows the ambiguous relationship of the polemarch and the

strategos

Archons chosen by lot

Ephialtes reforms the Areopagus; powers given to Ekklesia, Boule, jury courts

ffi

FTGURE

8.f 3

Archonship opened to the third property class, the Zeugitae

Pericles introduces payment for jurors (payment for magistrates adopted later)

Citizenship law of Pericles

Major changes to Athenian democracy

THE

WORLD:

5OO-44O

BC

257

The structure of goverrunent

Radical democracy

In studying this period it is vital to understand

the

nature of political power in Athens. 'Men became conspicuous in Athenian political life through the reputa-

tion of their families and the social circles to which

they belonged, from their association with and influence on members of the Council of Five Hundred, and

from their ability to win favour in the assembly.ÌO

Athens became more democratic with the introduction

of a system of changes that allowed greater participation by ordinary citizens. This is frequently referred to

Summary of reforms introduced in this period

o development of popular courts

o introduction ofpay forjurors and officials

o abolition and reduction of property qualifications

for magistrates

o selection by lot for most officials

o limitation of magistrates

o the people, through the Ekklesia,

the Boule and the

law courts, gained sovereignty.

The archonship and selection by lot

as'radical democracy'.

It was considered radical because of:

selection by lot

Confusion had arisen about the powers of the archons.

o

o rotation ofoffices

o collegiality

o

GREEK

In 501 BC the strategos had taken

some of the

archon's functions. The battle of Marathon demon-

payment for service.

In the radical democracy of Athens it is unlikely

that anyone really poor became a political leader

because of the amount of time that leadership

required. A significant change had occurred during

the Persian Wars. It became clear that political power

lay with the class best able to defend the state. The

navy was successful in the Persian Wars, and the

strated the ambiguity surrounding the relationship

between the archon and the strategos. Kallimachos,

the polemarch (chief archon), was technically in

charge but the strategos Miltiades had been elected by

popular vote and possessed military experience. This

situation showed that the chief archon was superfluous. Afterwards the archonship was downgraded,

probably as a response to the situation at Marathon.

Thetes-from among whom the rowers

were

enlisted-demanded greater political power, which

led to a radical democracy.

Throughout the 5th century Athens developed a

large maritime empire based on trade. However, it is

important to note that the basis of Athenian society

pn thc year 487/6 BCl, in th,e archnrxhip of Telesinw,

they selected.,for thef.rst timc sin'ce the tyranny, the

nítæ archons by Int through th,e tribes, from o'nlong

500 cand,id.øtes prniously elected by thc d,em'esmen.

remained agrarian. Landholding continued to be a

significant determinant of success. The main agrarian

Preuiously, the archons had' all been elected, by uote.

classes were as follows:

o Pentakosiomedimnoi-owned

ARtsrorLE, Constitution of Athens, trans. by

K. voN FRtrz & E. Kaee, p.92

land that produced

500 medimnoi a year (modem equivalent about 30

hectares)

o Hippeis---owned

land that produced 300 medimnoi

(also furnished a horse for cavalry service)

o Zeugirae-owned land that produced

o Thetes-owned property of less value than

the

above.l1

David Stockton calculates that the average

Athenian family-a man, wife and three childrenwould need about twenty-five medimnoi a year to

survive. (The medimnos was an Attic unit of measu¡s-¿þs¡¡

Up to this time the archons had been directly

200-300

medimnoi a year and owned plough and mules

105 bushels; in liquid measure about 50

litres.)

loFine, op. cit., p. 385.

'rFigures from D. Stockton, The Classical Athenian

Democracy, Oxford University Press, Oxford,1990, p. 7

elected. From 48716 BC the archons were chosen by

lot from the top two Solonian classes-the Pentakosiomedimnoi and Hippeis. This change to the archonship

had a number of consequences:

o Not only was the status of the archons weakened

but the polemarch lost his command of the army

and his control of the Ekklesia, becoming a mere

figurehead.

o

The office of strategos became the important military and political position, for the generals gained

the command of the fleet and the army. After the

formation of the Delian League the strategoi were

also the commanders of the military and naval

forces ofthe League.

25A

HISTORICAL

TABLE 8.f

PERIODS

Atheniøn political institutions afier Keisthenes' reforms

Institution Number and method

Functions and duties

Plaee of meeting

E x e cutia e cornmitte e ; pr ep ar e d

agend,a for the Ekltlesia;

formulated, motions on which

The old Bouleterion.

When the mernbers were

on d,uty they stayed, in

tlrc EkkLesia aote.d.

the Tholos.

Elected magistrates; aoted, on

importønt rnatters of state.

ofthe Areopagus.

Judged legøl rnøtters and

In or near the Agora.

of selection

Boule

(Council

of 500)

50 cítizerufrom each tribe.

Ekklesia

All male citizens

(Assembly)

age of eighteen.

Dilçasteria

or Heliaea

All male citizens

ouer the

oaer the

ageofeighteen.After

Ephiahes' reforms all jury

courts u)ere called, \teliaea'.

In the Sth century these

courts'Dere staffid by jurors

The Pnyx, west of the

híll

archons'decisions;afterEphialtes'

reforms the courts d,eterrnined,

the suitability ofpotential

ffice holders ønd, held,

magistrates to account.

(dikastai), and the courts canle

to be called'dikasteña'. 6000

citizens (600from each tribe)

oaer the age of thirty were chosen

as a pool ofjurors. Jury sizes

aaried.from 201 to 501.

Strategoi

l0 generals (onefrom eaclt,

tribe) elected, by the Ekhlesia.

Seraed, as

military

responsible

command,ers;

Strategion near the Agora.

for recruitment to

the arm.y.

Archons

Elected, by citizens but

eligibilíty entailed

Areopagus

Wid,e powers, becøuse they were

members of the Council of the

rnembership of the top two

economic classe.s.

Areopagus.

No set number. Mad,e up

of ex-archons elected,

Held executiue power in terms of the

law and cowtitution; administered

the state. After Ephialtes'reforms the

Areopagus had the care ofthe sacred,

for life.

Office øt the Royal Stoa.

The

híll of the Areopagus.

oliae trees and, ad,judicøted. in arson

and homicid,e cases.

o By decreasing

the importance of the archons, this

Iaw also devalued the role of the aristocratic council of the Areopagus. As this council was made up

of ex-archons, 'it would not take long for the change

to selection by lot to alter the makeup of the

Areopagus, and with it the status and respect it had

previously enjoyed'.l2

By 457 BC the archonship had been opened to the

third property class, the Zeugitae, and some time after

that to the Thetes. This meant an increased oppoftu-

nity for Athenians to participate and fewer distinr2J.

Thorley, Athenian Democracy, Routledge, London,

1996, p. 53.

guished men being chosen. This change to the archon-

ship may have been the work of Themistocles.

Certainly, Themistocles benefited the most from these

changes to the archonship and strategoi and the

ostracisms that followed.

The aristocratic idea that political office required

special expertise was changing to the radical ideal

that there should be equal involvement of all, except

in military affairs. Policy was being made by large

popular bodies and the magistrates were carrying out

the will of the people. Direct election, however, was

still used for those officials who did require expertise,

such as the generals, architects and supervisors of

public works.

THE

GREEK

WORLD:

5OO-44O

BC

259

The strategoi

'by the device of ostracism he and his collaborators

Early in the 5th century the criteria for choosing the

strategoi changed. A fragment from the Sth-century

comedy writer Eupolis tells us that once the strategoi

had come from the great houses and were chosen

because of their wealth and birth, but by the iime that

he was writing it was different. Henceforth, ambitious

Athenians and members of the great families could

choice between their leaders, and was used by

Athenian leaders to rid themselves of their political

opponents. The use of ostracism reveals the importance of political leaders and that politics in Athens

seek power and influence through the office of strategos. The election of the generals took place in the sevenlh prytøny. The introduction of the election of one

strategos per tribe (in 46918 or 460159) may have been

a reform of Ephialtes.

In 460 BC two of the generals, Aristides and

Ephialtes, were not from the Athenian élite. Both were

prosperous landowners but presented themselves as

friends of the people. They were not involved in the

aristocratic political clubs or hetaireiai' They believed

in strong leadership and popular participation in

govemment.

Rotation of offfce

Another important element in widening the democracy

was the introduction of rotation of office, so that politicians could not hold office continuously and could not

eliminated their chief opponents one by one'.14

Ostracism was a means of offering the people a

was driven by personalities.

Keisthcrcs enntted' new flautsl with the aitn of winning

thc peopLe\føuour. Amang thcse was th,e lant of

ostracism. . ,

Whcn, inthc twelfih year afier thcse innouatiorx, in

airtory

tuo ntare years had, passed ofær

th.e arch,onship of Ph,onnipptu, they had, won thc

of Marathnry and, wh¿n

that bøttle, and. the comtrnn peoplc gøinnd' greater selfconfàcnre, thcy emplayed.for thnfirst timc the law

coræerning ostrocisrn. Thß laut ha'd' been etmcted,

because of thcir suspirinn of thnse inpmter . . .

In thn sinth prytany . . . thcy al'so dcciÅn by uoæ

wh¿th.er thcre ß ø be a1)ote otu ostra'cism or twt . . .

ARlsrorLE, Constítutinnof Athcns, trans. by

K. voN FRlrz & E. KAPP, PP.91, 117

become dependent on state pay. According to

Aristotle, no one could hold the same office twice

except for the generals and the members of the Boule:

'The military offices can be held repeatedl¡ but none

of the others can, with the exception of Council members who can belong to the Council twice [in their lifetimel' (Constitutioru of Atherw, XXII, 3). The principles

of selection by lot and rotation of office ensured that a

representative cross-section ofthe citizens took part in

the govemment. This practice of rotation of office can

be seen in operation at ihe battle of Marathon: 'The

generals held the presiding position in succession,

each for a day; and those of them who had voted with

Miltiades, offered, when their turn for duty came, to

surrender it to him' (Herodotus, Histories, VI, lIt)'

Use of ostracism

A major change that occurred in 4BBl7 BC was the use

of ostracism. The sources conflict about who was

responsible for formulating ostracism law. Aristotle

claims that it was Kleisthenes who made the law but

that it was not used for twenty years' The lexicogra-

This senterce of ostra.cßmwo,s nnt in i*elf a punßhmcnt

for wrongd,oing. h wøs d¿scribed'for thc sakc of

appearønres os a fitÊøsure to curtail and' hwnblc ø

man's ptruter and prestige in cases whnre thnse h,etd,

groûn oppressiue; bw in reality it was ø hurunæ deuù:e

.for appeosing thc peoplc's jealottsy, uthich could' thtts

uen¡ its dcsire to do harm, not by inJli,cting some

irreparable injury, ba by a senleru:e of ten years'

banßhm,ent..,

Eoth aoter tool¡ an ostrakor¡ or picce of eartheruttare,

wrote on it th,e mme of thn citizen h¿ wished' to be

banish¿d, and, carried, it to a part of th'e mnrkct-plo'ce

which was fented off with a circular paling. Then thc

archonsf,rst courúed the totøl nurnber ofaotes cast,for if

thcre were l,ess than 6000, the ostrarßm was ttoid.. After

thß th.ey sortnd the aotes and the mnn wh,o ho'd, the mnst

recordcd, against hß nømc wos proclaim'ed to be exiled

for ten years, uith the right hnweuer, to receiae thc

inromcfromhís estate.

pher Harpokration refers to the ostracism law as having been enacted in 4BBl7.13 Hignett suggests that

Themistocles, Ieader of the anti-Persian party, may

have been the originator of the ostracism law because

r3Fine, op. cit., p. 240.

PLUTARcH, Thc

Rise and'

FaIl of Athcrc, trans. by

t. sqorr-K¡LvERT,

raC.

pP. 116-17

Hignett, A History of the Athenian Constitution,

Oxford University Press, London,1970, p. 1BB.

260

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

o By his persuasive tongue and clever strategies

he

held control over the Ekklesia throughout the

o

fThemistocles] wos the only man who had, thc courage to

come before thc peopl,e and propose that the ret)enue

from thc silaer miræs at lnurium, whi.ch the Atheniørc

had, been in thc habit of d,iaid,ing unng themselues,

shnuld, be set osidc and thc money wed, to build triremcs

for the war against Aegim. This conflirt, øt that

mam,ent the mnst important in all Greece, was at its

h.eiglu anÅ. thc island,ers, thanlæ to thc size of their fl.eet,

uere mo,sters of th,e sea. This made it all the easier for

Thetnßtoclcs to carry his point. There uas nn tæed to

4

Ostrakafrom the Agora in Athens

showíng the nq,mes offour prominent Athenian

FTGURE 8. t

politicians

Q/n dntt / an

lt'ng

/6e ,out"e"

an

I

us

tng

:

Usirug the sources, explain th,e purpose of ostracism.

s

How was it organised,?

t

What was the penalty?

s Refer to Figure

8.14.

Persian invasion of 4BG-79 BC.

Themistocles advocated a strong anti-Persian policy; after the Persian Wars he pursued anti-Spartan

policies.

tenifu thn Atheniaru with the threat of Darius and the

. The resuh uas that the Atheniaru built 100

trirem.es with the mnnÊy, and, th.ese ships artuallyfought

Persiøræ . .

at Salarnis øgaiut Xerxes .. .

He twnnd [thn Athcnians], to we Plato's phrase,frorn

stead,fast hnplites into sea tossed, mariners, and, he

earncd,for himself thc charge that hc had dnpríaed thc

Athenians of th.e spear and, thc shinld and. degrødcd

thcm to thc rowing beru:h and th.e oar . . .

Whose nanles appeØr on the

ostraka?

9"tfut/6e, tnues/tga/ìon

Three of the men nømed. in Figure B.14 were

ostracised, Research the circumstønces of eøch

Afur this h,e proceed.ed, ø d.euelnp th,e Piraetu as a

port,for hc had, alread.y tahen nnte of thc rntural

ad.aantøges of its harbours and, it was hß ambition to

ostracism.

unite th,e whole city to thc sea . . . h.e attached thc city to

thc Pira¿tr and mad,e th.e land. dcpendnnt on the seø.

Øc/hz/V

The ffict of this wos to increue thc influerce of the

peoplc at the expense of thc rnbility and, to fill them with

conf.deræe, sinre the control of policy nmn passed, into

the ha.nd^s of sail,ors and, boatswains and, piloæ . . .

[Inter thc Thirty Tyrønts] beli.eued that Ath.ens'ruraal

ernpire ha.d. prcned n be thc mnther of demoøacy and.

Using Plutørch's instructions as a guid,e, condlrct your

own ostrecism in cløss.

Themistocles

Themistocles can be regarded as the political successor of Kleisthenes. Following are the significant

changes that took place in the time of Themistocles:

o In 49312 BC he fotified the harbour of the Piraeus

and in the 470s completed the walls protecting the

Piraeus.

that an oligarchy was mnre easily accepted, by mcnwho

tilled, th¿ soil.

PLUTa,RcH, The

Rise and,

Fall of Athens, trans. by

t. scorr-KtLyERT,

pp. BGSI,96

o In 483

o

o

BC he convinced the Bkklesia to use the

profits from the silver mines at Laurium to develop

and build a fleet of 100 triremes.

Themistocles' development of a naval policy; transformed Athens from a land power into the leading

maritime state in Greece.

During the 4B0s Themistocles used ostracism as a

weapon against his political opponents. (It may also

have been an attempt to rid the state of suspected

Persian sympathisers.)

Q/n

lntt

/an

ltng

an

I

us

tng

/6e sources

:

How did Themistocles corwince the Athenians to

build, a nøay? What political changes did this

stimulate?

)

Whql other changes d,id, Themistocles malæ? How

important were they?

THE

WORLD:

GREEK

At

BC

5OO-44O

26t

last euen his fellow citieeru reo,ched thc poin at whirh

jealowy madc thetn listen to øny slan'r)'er at his

th.eir

expense, and, so Themistocl,es wasforced' to remínÃ' th,e

of his arhíeuemen¡s until thny could, beør thß

rw longer. He once said to those who were complaining

of hitn: 'Why are you tired' of receiuing bercfi'ts so often

frorn. thc samn men?' Besidcs this h'e gøae ffirce to the

people wh.en he built thn Temple of Aræmis, for rwt only

did,h.e style the god'dnss Artemß Aristoboule, or Artemß

wßest in couttsel---<tith thc hint that it wos he who ha.d

giaen th,e be;t counsel to thc Athcnians ønd the Greelæbut he chpse a siæfor it near hß own h'otne at Melite.

Assembly

FrauRE

8.15

PLUTARcH, The Rise and' FalI of Athens, trans. by

l. Scorr-Krrvent, p.98

Themistocles' walls

From the archaeological evidence found

Themistocles' do*rrfall

in

the

it

seems that Themistocles had been subjected

throughout the 4B0s to an organised campaign to have

Agora

After the Persian Wars, Themistocles' power declined.

While Kimon and Aristides weïe working on the

Delian League, Themistocles was in Athens in 478 BC

supervising the building of the Long Walls. The

Spartans strenuously objected to the rebuilding of the

walls but Themistocles pushed it through despite their

antagonism. A. Podlecki comments that it is 'legitimate to deduce that Themistocles' exposure to the

Spartan mentality in 480, when he had to deal with

them as often unwilling allies, had convinced him that

him ostracised. Archaeologists uncovered many

they, and not the Persians, presented the real obstacle

/6e sour"es

Athens' greatness'.15

League forces under the leadership of Kimon

and Aristides enjoyed numerous successes in the

470s. This would have seriously undermined the political position of Themistocles. Thucydides informs us

that the height of Themistocles' walls was about half

to.

'The

what he had planned (Peloponnesiøn War,I, 93).

Perhaps this was how the Ekklesia responded when it

heard of the great success of Kimon at Eion-if the

Athenians were so successful against their enemies

they probably considered it unnecessary to have such

high walls.

Themistocles tried to remind the Athenians of his

important contribution during the Persian Wars. In

476P,C, he was choregw for a tragedy by Phrynichus,

The Phoenician Women, which dealt with the Persian

defeat and no doubt reminded the Athenians of his

role in those events.

in the same hand, with Themistocles'

name, suggesting that it was not an individual vote but

ostrako, incised,

an attempt to rig the ostracism. In 472

Themistocles was ostracised and, initially, went to live

in Argos. He aroused anti-Spartan feeling in the

Peloponnese. The Spartans complained to Athens and

claimed that he had collaborated with Persia.

Q/n dnrt /on

J. Podlecki,The Life of Themistocleso McGill-Queen's

University Press, Montre at, 1975, p. 34.

lrny an I

us

tng

:

:

:

;

ReadThucydides

:

)

What d,eal did' Themistocles strilte with' Art(rxerxes?

I, 134-8, pp. 115-17'

How d,id, Thetnistocles respond to the clmrges? Why?

How was Corcyra in'aolued in these eaents?

What part d.id, Ad,metus of Molossi

Tlt ernistocles' flight?

play in

How d,id, Themistocles support himself during this

time?

:

:

Hon did Themistocles die?

Sum up your uiews of Themistocles' character.

Øc/ioily; le6o/e

Tlt

etnistocles: uisionary genius or opportunistic

traitor?

Øc/ioilV;

r5A.

BC

Wha,t

essag/

political influence did Themistocles

period,?

h,øue iru this

262

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

Aristides

thnught th,emselues cøpablc of ønything and, were

ffindcd at anybod,y whose tultno and, reputatinn rose

aboue the comm.on Leael. So thcyfuclæd, into th,e city

frorn all ouer Atti,cø ønd, proceed,ed, to ostracke Arßtidcs,

d,isguising thcir jeølawy of hisfame undcr thc pretext

th,a.t thcy were afraid, of tyranny.

Aristides (not the general of 460) came from an aristocratic background and tended to be politically conservative. Throughout the 480s, along with Themistocles,

he advocated an anti-Persian foreign policy. If the law

on ostracism was enacted at this time, as many scholars believe, then Aristides was likely to have been one

of its promoters, as the first victims of the ostracism

law were Persian sympathisers. However, Aristides

opposed Themistocles over the naval bill, as it would

weaken the dominance of the hoplite army and

increase the power of the Thetes in the navy (at the

expense of the aristocrats' power).

PLUTARcH, Th¿

Q/n

ofthc people . ..

Th.emistocles was corwtantly proposing reckless

reforms ønd, at the same tim.e checking and, obstrutting

hiln at euery step in thc btuiness of goaemment, Aristi.d¿s

wasforced, to oppose Th¿mistoclcs' mcasures in thc samc

fashion, partly in self-dcfenre ønd. partly to limit his

opponent's power, whirh was constøntly grming with

the support of thc people. He thought it better that thn

people shnuld,forgo an occasinnal ød,uantage than that

Themisnclcs should get hß rtay on euery occasinn ønd,

he opposed, and,

dcfeated Thnmisøcles øt a rnnment wh,en th¿ løtter was

trying to ca,rry a really ræcessørrt fitßosure, and, thcn

Aristidns could, nnt refrainfrom saying, as he lcfi thc

Assembly, that there would be ru safety.for Athcru unless

the peopl.e thrøt both Themßtocles and himself inø thc

børøthrum.

PLUTARcH, Thn Rise and, Fall of Athcn^r, trans. by

t. ssorr-KtLvERT, pp. lll-12

opposition,

in

I

d.id.

us

p. 116

tng

Aristides oppose

Whøt d,o you think is meant by Aristides' conrn'Lent

that both men should, be thrown into the execution

pit?

Thcmistocl,es, th.e son of Neocles, who was thc chørnpi,on

In order to hinder Aristides'

an

Accord.ing to Plutarch., why

Themistocles?

:

Themistocles spread rumours about him and

BC succeeded in having him ostracised.

lnrt lan ltng

/6e sources

Aristidcs supported an aristocratbform of goaernmcnt

and. so constøntlyfound, himself in oppositinn to

Bafinally

Fall of Athnrc,trans. by

l. Sqorr-Ktlvenr,

;

carry all before him.

Rise and,

482

Themi"sncles put about thc story that by thefan of hß

arting as arbitrator and. jud.ging all cases referred, to

him in priaate, Aristidcs had, abolished, the public courts,

and. that without anybody noticing it, hc hød rutdc

himself oirtually the ruler of Athens, ønd, only lacked an

armcd bodygunrd, . . . th.e people had. becomc so exultant

becanue of th,eir airtory ouer the Persians that thny

a

What was the runlour thøt Themistocles spread,

øbout Aristides?

s How are the people of Athens presented,

in

these

pøssages?

a

What

d,oes

Plutarch tell us about the worltings of

Athenian politics?

Kirnon

Kimon played a vital role in the development of the

Athenian Empire, and by his attitude contributed

unwittingly to the further democratisation of Athens.

Although from a noble famil¡ Kimon enjoyed grei.'.

popularity with the masses, which he fostered by offeiing generous gifts to the state. He followed a new policy of panhellenic idealism, showing particular favour

to the Spartans.

L

Thc Spartans on thcir sid,e did, mu.ch to strengthen

Kimon's positinn, o,s thßy soon becamc bitterly hnstile to

Th.etnßtocl,es and, were thcrefore concerned that Kimon,

young os hc was, sh,ould exercise greater power and,

influcrrce at Athens. Atfirst thc Athcniatæ were well

pleased at this, siru:e the good,will thc Spartans shnued

th,em was uery mtrch to their odaantage . . . But

afterutards, wh,en thcir puler had grown and, thcy saw

that Kimon was whnleheartedly attochcd to th,e

Spartans, they resented, this, rwt least because of his

tenderrcy to sing the praises of Sparta to the Ath,enians

wh,eneuer he had, occasion to reproarh them or spur

th,em on,

PLUTARcÞI, Thc

Rise and.

Fall of Athnrx, trans. by

l. ScoTT-K¡lvenr,

p. 158

THE

Kimon of course played a

paÍ in bringing charges

against Themistocles for medising'

He

joincd with Arßtid,es in opposing Themistocles, when

the latter began to extend the a'uthority of the people

beyond its duÊ lirnits; and, later on he also resisted

Ephialtes when, to please the people, he tried' to d,issolue

the Courrcil of the Areopagw.t6

\¡1/ORLD:

GREEK

5Oo-44O

BC

263

attenxpts to conÍentro'te offæe anl'pttwer intheir own

hands, but oilyþr as long os he was in Athens. Th.e

nnxt timc tha,t h.e sailed anay onforeign seraire the

people broke loose from all control.

PLUTARcH, Thc

Rße ønd'

FalI of Athens, trans' by

p. 157

l. Ssorr-Kllvenr,

There appeared to be a contradiction between his

policies abroad and at home. As leader of the Delian

League forces he met with considerable success.

These successes, however, also increased the importance of the fleet and the Thetes. At Athens he

In 462 BC the Spartans asked for assistance with

the helot revolt at Mt lthome' Kimon, very proSpartan in his policies, enjoyed good relations with

resisted any moves to change the constitution. Instead

Spartan request.

the Spartans and favoured sending an expedition to

help them. Ephialtes urged the Ekklesia to refuse the

he attempted to divert the Thetes from political

changes by distributing gifts and giving poorer citizens the opportunity to obtain land in the colonies.

Kimonwas alread,y a ri't:h mnn, and'

so h¿ saw to

þarn'd

support' but

thc

Spartøns,

th.eir boldnnss and, enterprise frightennd

wha singl,ed them outfrom amnng all the allies as

dangerotn reoohttíonari,es and' sent thcm atttøy. They

Thc Athenians

it that

onÆe

Ítore caÍæ to

the mnney which he was cred,itcd' with hauing won

horcurablyfrom th'e en'em'y in his campaigns u)oß spent

euen Ítore honnurably on hisfellow citizens- He had all

thcfences on hísf'elds talæn dnwn, so that twt only poor

returncd hom.e in afury an'd, proceed¿d n take publir

rnenge upon thelriends of Sparta in gencral and,

Kimon in parti.cular. They seized, upon som'e trifling

pretetû to ostradse him an'd, con'd,emtrcd, hitn to exile for

Athenians but euen strangers could hclp themselues

ten,

season. He also prouidnd a

din¡ær at his hotne euery d'ay, a simple mcal but enough

for large numbers. Any poor manwho wishnd could'

comn to himfor thß, and' so receiaed, a subsistence whi'ch

cost him nn ffirt and' left hirnfree to deuote all his

are banished' by ostro,cism.

freely to whateuer fruit was ín

a.ttention to pubLic affairs . . .

. . . the story was spread that

flatter thc

mnsses o'nd,

PLuraRcH,

In

all

thß was only dnæ to

cunyfaaour with

th,em'

Th¿ Rße and Fall of Athen's, trans. by

l. scorr'KlLvERT,

PP' 151-2

46514 BC Kimon was unsuccessful

in Thrace

and his political opponents, Ephialtes and Pericles,

decided to prosecute him for taking bribes from

Alexander, King of Macedonia.

I

So Kimnn was a,cquitted on thß occasion. During the

rest ofhis political career he succeedcd in arresting and

euen

reducing

th.e eru:roa.chm'ents

of the people upon th'e

prerogøtioes of the arßtocra'cy, an'd ínfoiling their

years whi.ch is th,e peri'od laid dawnfor all those who

PLUTARcH, The

Rße anÅ,

FaIl of Atherx, trans. by

p. 160

l. sqorr-Kllvenr,

When Kimon went to help the Spartans in the

cause of panhellenic friendship, he took with him

4000 hoplites. The {leet and the Thetes were not

needed on this occasion. Ephialtes seized the opportunity of Kimon's absence to pass his laws limiting the

powers of the Areopagus' Meanwhile, Kimon was

rebuffed by the Spartans and had to retum to Athens.

The more radical democrats in Athens blamed Kimon

for Sparta's intolerable behaviour. Kimon was

ostracised in 461 BC.

(Un

ln.t / on lt'ng

an

d u s tng

/,6e sources

:

:

How did the Spartans regard' Kimon?

Why did the Athenians become an'noyed with

Kímon?

r6Plutarch, The Rise and,

Fall ofAthens, trans. by I. Scott-

Kilvert, Penguin, London, 1969,P. I52.

;

;

Why did, Kimon' oppose political change?

Why did the Athenians ostracise Kimon?

264

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

Zc/iui/y.'ers a/

How important was the contribution of Kimon

period?

in

this

Ephialtes' reforms

The most significant of the democratic changes

occurred

in

4621L BC, when the Ekklesia, the Boule,

and the jury courts were given a greater role. Little is

known about Ephialtes, the man responsible for these

changes. He was probably of humble origins. It is

clear that he became the democratic leader after

Themistocles and successfully prosecuted members of

the Areopagus for corruption. It is unlikely that he

was a very poor man because he became a general in

c.465 and led an expedition to Phaselis. EaÃy in 462

he unsuccessfully attempted to impeach Kimon on

comtption charges. Later that year, he opposed send-

This, then, was the way in whi.ch the people obtaircd

thcir liaelihoods. For seuenteen years following th.e

Persían Wars, thc politiral ordcr remøiræd, essentiølly

the same undcr the superaßinn of the Areopagus,

ahhnugh it was slmtly degenerating. But as the

commnn people grew in strength, Ephialtes, thc son of

Sophonidcs, who had, a reputationfor intomtptibility

and loyølty to the co¡xtitution, became teøder of thc

people and, mad¿ an atta.clt upon thc Areopagw. First he

eliminated, rnany of its members by bringing suits

agairct thcm on the ground of adrninistratiue

in thc archonship of Kornn, hn

Courcil of all thnse prerogatiues which it

¡niscond,uct. T\rcn,

depriued, thn

recently had, orquíred, and, whi.ch had made it the

gtnrd,iøn of thc støte, and gøae somc of th.em to thc

Council of Fiae Hundled, sonte to th.e [Assembly of thc]

people and, somc to th,e lcrut courts.

ARtsrorLE, Constitutian of Ath,erc, trans. by

K. voN FRrTz a e. Xan¿ p.95

ing Athenian help to the Spartans, for like

Themistocles before him he recognised that Sparta

was a rival to Athens.

In 462, Ephialtes made major changes to the

democracy at Athens. Ephialtes' actions were

designed not only to widen the democracy but also to

counter the influence of the conservative leader

Kimon, who at the time was in the Peloponnese.

Kimon was known as a vigorous supporter of the

Areopagus, and earlier in his career had opposed

Themistocles' plans on behalf of the people.

Before 487 BC all important political leaders of

Athens were archons, who, at the close of their term of

office, automatically became life members of the

Areopagus. Only men from the top two economic

classes, and over the age ofthirty, were eligible for the

Areopagus. This conflicted with the democratic ideal

of participation by all.

Scholars are unclear about the exact nature of the

jurisdiction of the Areopagus at the beginning of the

Sth century. Aristotle mentions that the Areopagus

was supreme in that period and that during the

Persian Wars it had taken on extra poweïs because of

its responsibility for the bartle of Salamis.

(Un

lntt /an ltng

/Âe ,out"e"

an

I

us

tng

c Vlhat changes did Ephialtes make?

; How d,íd. Ephiahes begin his attack or¿ the

Areopøgus?

Ephialtes charged men from the Areopagus for

using powers they were not entitled to use. In this

period there was also a great deal of competition

between the members of the Areopagus and the strategoi. What were these powers that the Areopagus was

supposed to be using unlanfully?

..

follaring Ephialæs'

lead they dcpriaed thc .. . .

Areopagus of all but afar of the isstæs whirh had, been

.

under its juri,sdictinn. They took control of the couræ of

justice and transformcd thc city into a thoroughgoing

d.emncracy

with the help of Pericl,es, whn had. ru¡w risen

to power and. committed himself to thc

cawe of the

people.

PLUTARcH, Thc

Rße and.

Fall of Athens, trans. by

l. ScoTT-Ktlvenr,

p. 157

o dohimasia-the examination of public

officials to

determine their fitness or suitability for office

o eisangelia-Ihe

power to supervise the conduct of

officials during their year ofoffice

o euthynøi-the investigation at the end of their

office to establish whether they had acted according to law.

By using these powers, the Areopagus may have

been able to ovemrle the actions of magistrates and

the Ekklesia. Ephialtes took away the added judicial

powers of the Areopagus through which it guarded the

THE

laws. The Areopagus was left with religious powers

and the right to adjudicate in arson and homicide

cases. Ephialtes' reforms blotted out the moderate

voice of men like Kimon.

Aeschylus' play The Eumer¿id,es offers important

evidence for the political climate of these changes. It

deals with the trial of Orestes for the murder of his

mother. The Eumenides are the Furies or, as the

Greeks called them, 'the kindly ones', who pursue

Orestes to exact punishment for his crime. Orestes is

tried before the Athenian law court of the Areopagus,

where he is acquitted.

It is not unlikely that

Aeschylus' treatment of the Orestes myth was heavily

influenced by contemporary events.

Arntwt: Citizeru

of Athens! As you now try

thisfi'rst

cose

Of btoodsh,ed, h¿ar the constitut'iøn of your court.

From this d'ay forutard' thß jud'icial coun'cíl shall

For Aegetn' race hear euery tríal of homicid,e.

Here shall be their perpetua'l seat, on Ares' Híll . . .

Here, ilay and night,

Shalt Awe and' Fear, Awe's brother, check my cítizens

From. all mßdníng, while they leeep my lauts wrchanged,.

If you beþul a shining spring with an impure

AnÅ, mud'dy d'ribble, you will comc in tnin to d'rink'

taint pure laws with new expediercy . . you a court inui'olable,

establish

I here

quick

to anger, ltcepingfaithful watch

and,

Holy,

sleep

in peaæ.

mny

men

That

So, dn not

AEscHYLUs, Eumznidcs, trans. by PHtLIP

vELLAcorr,

pp. 170-1

In these lines Aeschylus is celebrating Athens' sucoa

course between the despotism ofthe

cess in steering

Kimonian oligarchs and the anarchy of the Ephialtan

WoRLD:

GREEK

265

BC

5OO-44O

Ephialtic reform. Stockton suggests that when the

Areopagus was deprived of its powers, tbe grøphe

may have been introduced to act as a'brake' on illconsidered decisions of the Ekklesia.Ìe

The

jury courts

Another reform thought to have been made by

Ephialtes was the introduction of multiple popular

courts, Ihe d,ikastería. The powers of the Areopagus

were transferred to the Boule, the Ekklesia and the

d,íkøsteria. The courts were now responsible for deter-

mining the fitness of potential office holders.

Additionally, magistrates were accountable to the

d,ilrusteria for what they did in office.

Jury service became a popular part of Sth-century

life, particularþ once Pericles introduced payment for

jury service. Archaeological evidence reveals much of

ihe equipment associated with the jury courts, such as

the kleroterioru (allotment machine), k'lepsydra (water

clocks, for timing of speeches) and bronze ballots by

which the jurors voted guilty or not guilty. The precise

location of the jury courts in the Agora has been much

disputed.

Èphialtes' measures were not simply the product of

an ideological commitment to democracy. The reforms

were partly a response to trends prevailing in the Sth

century-the change in the role of the archons, the

growing strength of the nary, the increased hostility to

Sparta, the failure of Kimon's policy.

Ephialtes died shortly after the passage of his

reforms.

Who killed Ephialtes?

Aristotle, writing about ninety years after the event,

claims that Ephialtes was assassinated by Aristodicus

of Tanagra. Antiphon, an Athenian orator writing about

forty years after the murder, could not be so precise'

radicals'.r7

Ephialtes may also have been responsible for

incrãasing public awareness of state affairs. A 4thcentury Greek historian, Anaximenes, wrote that

'Ephialtes had the Athenian written codes removed

from the acropolis and set up instead in the Council

House and Agora'.r8 Anyone who introduced a law to

the Ekklesia that was later found to be detrimental to

the people could be charged' This was called a graphe

Thts

tht¡se who murd,ered'

d,ßcouered'

to this dny,

Jones, 'The role of Ephialtes in the Rise of Athenian

Democracy', Classical Antiquity, L9B7 , p. 75.

r8Quoted in Stockton, op. cit., p. 48.

if someotæ

expected'

hß

associates, to conjecture whn were [Ephiahes']

tnwderers, øn'd, if nnt, to be implicated in th'e murder, it

would, twt harte beenfair to the associates. In add,ition,

th¿ ¡nurd¿rers of Ephiølæs di'd rct desire to hide the

bod.y so there would be rn d,ønger of betraying th'e dned'

ANTIpHoN, cited in D. RoLLER,'Who Murdered

Ephialtes?', p. 258

porãno*on. The introduction of this law cannot be

positively dated, but some scholars view it as another

r?L.

Ephialtes . . . haae tæuer been

ønd,

Plutarch wrote his biographies during ùe lst century

AD. He addresses Ephialtes'death in Source 8.50'

lelbid., p.45.

266

HISTORICAL

PERIODS

)

How are we to belieue ldnmen¿us' charge that Pericles

arra,ngerl the ossassinatian of the dnmncratù: lead,er

Ephiahes, who was hüfriend., as well as his partner in

his politi.cal program, out of sheer jealowy of his

Other reforms

In 457 BC the archonship was opened ro the Zeugitae,

the third economic class established by Solon. This

reputation? . . . Asfor Ephiahes, the truth is that the

aristocrats hød, good, reason to fear him, sirrce he was

relentless in calling to aîcount and prosecuting those

uho had, in any uay harmed the peoplc, ønd, so his

enemi¿s conspired. against him and secretly arranged,for

hirn to be murd.ered..

PLUTARcH, The Rí"se

and,

(ù/ro

meant that half the male citizens in Athens were eligible to hold office. Shortly after this the Thetes also

became eligible for the archonship. It is unclear from

the sources exactly who was responsible for these

changes.

Fall of Athcru, trans. by

l. scorr-KtLvERT,

lntt / an lt'ng an I

ust

/6e sources

pp. IZS_ó

Participation in the demo cra,cy

How many people took part in Athenian government?

James O'Neil has estimated that there would have

been 15000 places to be filled, based on the fact that

500 councillors served per year and assuming thirty

years per generation.2o The chairman of the council

(epistates) changed every day. It should be borne in

ng

c Vlhy was Ephialres killed?

; Who does Aristotle blarne for Ephialtes' death?

a

What does Antiphon soy on this matter?

;

Who d,id, Idomeneus cløim was responsible?

Consider the uarious theories about Ephialtes,

d,o you consider the most plausible?

death. Which

whv?

2oJ.

O'Neil, The Origins and Deaelopment of Ancient Greelr

Democracy, Rowman & Littlefield, London, 1995, p. 67.

The Long Valls

Construction dates:

478 Piraeus fortified (begun prior to Marathon)

479

458

44847

Asora

Athens'wallsrebuilt

Athens

Themistocles'

walls

rll

North and south walls built

Areopagus

Middle wall built

.''

/z-¿

Pericles'

walls

/-

îhemistocles'

walls

I

È/

èt

Pericles'

Bay

walls

of

Piraeus

of Zea

Saronic CuIf

0

I

kilometres

FIGURE

8.I6

The walls of Themistocles and Pericles

2