* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Off-Pump Positioning of a Conventional Aortic Valve Prosthesis via

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Cardiothoracic surgery wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

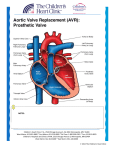

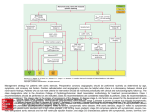

Off-Pump Positioning of a Conventional Aortic Valve Prosthesis via the Left Ventricular Apex With the Universal Cardiac Introducer® Under sole Ultrasound Guidance, in the Pig Gerard M. Guiraudon MD1,2, Douglas L. Jones PhD1,2,3,4, Daniel Bainbridge MD5 Terence M. Peters PhD1,2,6 , 1 Canadian Surgical Technologies and Advance Robotics, Lawson Health Research Institute, Imaging Group, Robarts Research Institute, Departments of 3Physiology & Pharmacology, 4 Medicine, 5Anaesthesia, 6Medical Biophysics, the University of Western Ontario, and the London Health Science Center, London, Ontario, Canada. 2 Corresponding author Dr. Gerard M. Guiraudon. CSTAR, Lawson Health Research Institute CSTAR Legacy Building, 7th Floor London Health Sciences Centre 339 Windermere Road, London, Ontario Phone: 519 685 8500 ext 32645 Cell: 519 643 86 10 Fax: 519 661 84 01 E-mail: [email protected] University Hospital Canada N6A 5A5 This work was supported in part by a CIHR grant (TM Peters, PI), and funds from the Department of Surgery (UWO). Running title: Off-pump Aortic Prosthesis Implantation using UCI 1 Off-Pump Positioning of a Conventional Aortic Valve Prosthesis via the Left Ventricular Apex Via the Universal Cardiac Introducer® , Under sole Ultrasound Guidance, in the Pig 2 Summary Objective: to test an alternative to catheter and open-heart techniques, by documenting the feasibility of implanting an unmodified mechanical aortic valve (AoV) in the off pump, beating heart using the Universal Cardiac Introducer (UCI) attached to the LV apex. Methods: In 6 pigs, the LV apex was exposed via a median sternotomy. The UCI was attached to the apex. A 12mm punching-tool (Punch), introduced via the UCI was used to create a cylindrical opening through the apex. Then the AoV, secured to a holder, was introduced into the LV, using transesophageal echo (TEE), guided through the apical LV opening, navigated into the LV outflow tract and positioned within the aortic annulus. TEE guidance was useful for navigation and positioning by superimposing the aortic annulus and prosthetic ring while Doppler imaging verified preserved prosthetic function and absence of peri-valvular leaks. The valve function and hemodynamics were observed before termination for macroscopic evaluation. Results: The Punch produced a clean opening without fragmentation or myocardial embolization. During advancement of the mechanical AoV there were no arrhythmias, mitral valve dysfunctions, evidence of myocardial ischemia or hemodynamic instability. The AoVs were well seated over the annulus, without obstructing the coronaries or contact with the conduction system. The ring of AoVs was well circumscribed by the aortic annulus. Conclusion: This study documented the feasibility of positioning a mechanical AoV on the closed, beating heart. These results should encourage the development of adjunct technologies to deliver current tissue or mechanical AoV with minimal side-effects. Key words: Aortic Valve Implantation; Off-pump Beating Heart Valve Surgery; Valve Repair/Replacement. Universal Cardiac Introducer. 3 Introduction In its early days, cardiac surgery developed very successful closed beating heart approaches15 that were abandoned for maximally invasive open heart techniques6-10. In the late seventies and early eighties, attempts to return to less invasive approaches were made for coronary artery bypass grafting, and arrhythmia surgery on the closed, beating heart11-15. In the mid-nineties, this concept became better understood and widely accepted under the heading of “minimally invasive” surgery16-19. This principle is at the core of our new project designed to meet two objectives: 1) reducing side effects without compromising the effective action on the target, and 2) broadening the patient population that will benefit with state-of-the-art valvular repair on both sides of the spectrum i.e. low risk and high risk patients. This project had to address 3 issues: 1) a safe and versatile intracardiac port access; 2) an imaging guidance system to substitute for the absence of direct vision, and 3) new appliances and tools to make the new approach safe and practical. Safe and versatile intracardiac port access was addressed by developing a special introducer to access all intracardiac targets: the Universal Cardiac Introducer® (UCI)20, 21 . The UCI was tested by accessing the left atrium for atrial fibrillation surgery22 and mitral valve surgery23 as well as the right atrium for ASD closure24. Aortic valve replacement, using an unmodified prosthesis, is the latest intracardiac target accessed via the UCI in our program. The designs of current AoV prostheses are the result of more than 50 years of basic and clinical research and provides excellent repair in terms of functionality and longevity25 . Unfortunately, AoV disease is prevalent in an ageing population with multiple morbidities, rendering the risk of AoV replacement excessive. Our experience with patients with multiple morbidities, such as patients with ventricular tachycardia after myocardial 4 infarction26, 27 suggests that correction of one of the multiple risk factors can have a positive impact on long term survival only if the surgical repair itself is associated with no mortality as suggested by the results of ICD implantation for ventricular arrhythmia28. Unfortunately, this challenging goal is not achieved with conventional AoV replacement. . Currently, the only alternative intervention for repair of aortic valve disease is percutaneous aortic valve implantation, via the left ventricular apex, using transcatheter techniques29-43. This approach is in the developing stage, and rapidly improving as documented in the presentations at the 2009 ISMICS meeting. Percutaneous implantation targets, for the time being, patients with prohibitive surgical risk for open-heart repair, but with experience, a patient population with optimal risk-benefit should be identified for this approach. We thought that a third surgical option will offer a more patient specific choice, and serve a larger patient population. The Universal Cardiac Introducer®, will provide a safe and versatile left ventricular (LV) port access for introducing, navigating, positioning and anchoring a stateof-the-art AoV prosthesis. We intend to duplicate the quality and reliability of conventional repair/replacement with much fewer side effects and risks. This new approach requires the parallel development of adjunct technologies such as a sophisticated image-guidance system 45, 45-64 44, , and other adjunct technologies that we already described, but documented feasibility was a critical argument to gain technical support for development. In this paper, we report our experience on the feasibility of navigating and positioning unmodified AoV prostheses, via the LV apex, using the UCI, under ultrasound guidance (US) in the pig. This feasibility study was also aimed at conceptualizing new technologies necessary to the development of this new approach. 5 Methods Animal model: Yorkshire-Landrace cross pigs were selected because they are used routinely in cardiac experiments in our laboratory 22, 23 . The protocol was approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Western Ontario and followed the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Although the pig is a well accepted model for cardiovascular research, its LV anatomy presents with significantly different features to that of the human. The porcine apex has a conical shape, with \the mitral papillary muscle attaching near the apex 65 , while the human heart has a dome-shaped apex with the papillary muscle inserting at a distance from the apex 66, 67 , this configuration made our apical access a little more difficult to avoid the papillary muscle. The cut is also different in humans or in dogs: it is a perpendicular cut in the human, while the plane of cut is slanted in the pig. The Universal Cardiac Introducer® (UCI) has been described elsewhere 20, 24, 68 . It was designed for access to all cardiac chambers. The UCI is composed of two parts: an attachmentcuff (the cuff), and an introductory-airlock chamber (the chamber) with sleeves for introduction of tools and devices (Fig. 1). The cuff controls the port access, and has a secure attachment to the heart chamber. It is made of a soft, collapsible material that is easily and quickly occluded by a vascular clamp. For insertion on the LV apex, the cuff had a flange that contoured to the ventricle and pledget and secure the attachment. The cuff has a safe connection with the introductory-airlock chamber. The chamber is impervious to air and fluids to prevent bleeding and air embolism. For this experiment the chamber had one sleeve, fitting the punching tool (Punch), or the valve and its holder. The chamber acts as a bubble trap, with its sleeves well above the heart port access, allowing venting of air before connecting the UCI to the LV cavity. The connecting system between the cuff and the airlock chamber is tight, resilient, and easy to 6 release. The drawing displays three sleeves, but, in this pilot study we only used one. The three will be needed when anchoring the valve for long term implantation. The Punch tool (Fig. 2), has been described previously 24. It was introduced into the UCI via the single sleeve. The diameter of the Punch was commensurate to the size the prosthetic valve. The Punch has a circular blade and a trocar. The trocar has a conic tip. The base of the cone is used as an anvil for the circular blade, while the tip is equipped with a transverse blade. The blade cuts a small ventriculotomy for introduction of the tip into the LV chamber. Then, the base of the tip is applied and maintained against the LV wall, while the circular blade is pushed with a rotating motion, to obtain a clean cylindrical excision of the apex. The excised myocardium is safely encased within the circular blade. The Valvular Prosthesis and the Valve Holder: the prosthesis was a St. Jude Medical mechanical aortic valve: the holder was a custom-constructed simple tripod attached to the handle of the commercial valve holder (Fig. 3). Because, positioning of the valve was verified by dissection in situ, there was no need for an anchoring-releasing system. US image-guidance with Doppler imaging was used as the sole navigation modality. A transesophageal echocardiographic (TEE) probe 48, 49, 51, 53, 57, 69-75 , with a 4-7 Mhz Minimulti TEE probe (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA) was introduced prior to tracheal intubation. A complete evaluation of the cardiac anatomy was performed, focusing on the LV apex, LV outflow tract, AoV annulus, as well as the mitral valve. Doppler imaging was useful for documenting the native AoV function before surgery, and later for monitoring prosthesis function and identifying potential peri-annular leaks. TEE guidance was the only image-guidance during navigation and positioning of the prosthesis. Virtual Reality (VR) image-guidance was not used in these experiments. 7 Animals: Six pigs were used. Following routine procedures 76, pigs were tranquillized with Telazol and Rompun before transportation to the laboratory animal operating room. After intubation, the pigs were mechanically ventilated and anaesthesia was maintained with mixture of nitrous oxide and 1-2% Isoflurane for the duration of the surgery. Limb lead electrograms, arterial blood pressure, pulse oximetry and end tidal PCO2 were monitored throughout. Heart exposure: For this pilot experiment, the chest was entered via a medial sternotomy, with the spreader placed in a lower position. The porcine LV apex is in a medial or para-medial position, adjacent to the sternum and is easily exposed via a medial sternotomy. The pericardial sac was open longitudinally. The LV apex was exposed by lifting the pericardial sac (Fig. 4). Universal Cardiac Introducer Implantation: The UCI was prepared and pre-clotted. The selected prosthesis was attached to its holder. The attachment cuff was attached around the LV apex using interrupted 2-0 Prolene® U-shaped pledgetted sutures. Then the introductory chamber was sutured to the attachment cuff, and the Punch was inserted into the introductory chamber (Fig. 5) Creation of LV apical port: The cutting edge of the trocar was positioned against and pushed through the LV apex. The base of the trocar was pull back and positioned against the endocardium of the apex. Then, the circular blade was pushed, using a circular motion, to cut a clean cylinder of myocardium. The excised myocardium was trapped in the cylindrical blade. The LV apical port was open, and safely controlled by the UCI (Fig. 6). US imaging was not used to guide the creation of the LV apex port, but was used to examine its configuration thereafter. The Punch was withdrawn into the chamber and the cuff was occluded using a Statinski vascular clamp. This manoeuvre allowed removal of the Punch from the chamber. The 8 fragment of excised myocardium was retrieved from the Punch to estimate the quality of the LV port access. Introduction of Aortic valve prosthesis: The prosthesis size was selected to accommodate the size of the aortic valve annulus determined by TEE measurement. The aortic valve prosthesis and its holder were then introduced into the chamber via the same sleeve, the UCI was filled with saline and the sleeve was tightly fixed around the holder using a tourniquet. The clamp occluding the cuff was removed and the chamber deairing was completed using needles punctures. The prosthesis was introduced into the LV chamber via the LV port, by careful manipulation. When inside the LV chamber, the valve was navigated and positioned using TEE guidance, and a 3D US probe applied epicardially, when possible. Navigation and positioning of the aortic valve prosthesis under US Image guidance (Figure 7): The TEE image was useful in documenting the native AoV normal physiology and its annular diameter. This helped select the size of the mechanical AoV prosthesis. All necessary landmarks were displayed on a single view of the LV cavity showing the LV inflow tract, mitral valve apparatus, LV outflow tract, aortic annulus and the cusps. After the AoV prosthesis had entered the LV cavity, US provided accurate guidance to navigate the valve along the LV outflow tract, while avoiding catching mitral valve chordae tendinae. It was easy to keep the prosthesis along the septum. Positioning of the prosthesis relied on two markers: 1) a tactile feedback felt through the AoV holder during manipulation, associated with the clear perception of the opening and closing click of the prosthesis; and 2) the visualization of the prosthetic ring over the annulus, its orientation parallel to the previous assessment of the annulus, and the absence or minimal peri-annular leak assessed via the Doppler Imaging. In addition, it was 9 documented that the prosthesis was functioning well with full opening and closure, and without valvular regurgitation. During these manoeuvres, there were no significant changes in aortic blood pressure. Since the valve and its holder were not obstructive of the left ventricle outflow tract, there was not hemodynamic change. When the valve was positioned it substituted for the native leaflets, without change in cardiac function. When the positioning of the valve was deemed adequate, the valve was maintained in place to the best ability of the surgeon during the post mortem examination. Post mortem examination: When positioning of the AoV was deemed final, positioning was maintained in situ, and the animal was killed by exsanguination. The introducer cuff was detached from the LV apex, and the opening of the apical port was extended along the LV free wall, parallel to the anterior interventricular sulcus, to expose the LV outflow tract. This allowed a good view of the prosthesis and the aortic annulus from above and its spatial relationship to the prosthetic ring (Fig. 8). When the evaluation from the LV outflow tract was complete, the heart was excised and positioning was re-evaluated from the aorta (Fig. 9). Results Attachment of UCI: The UCI fitted well over the LV apex. Interrupted U-pledgetted sutures provided safe and atraumatic anchoring without leaks. LV apical access: Used a traditional punching tool (Fig. 2), an adequate apical opening was obtained (Fig. 6). The resected tissue was trapped within the cylinder. No fragmentation or loose fragments of myocardium were observed. Introduction of the prosthetic aortic valve: The LV port was readily accessed. However, the passage through the port required some manipulating. The holder was presented to the LV 10 port in an oblique way to introduce the prosthesis sideways, pushed into the LV port while straightening the holder and finally introduced smoothly into the LV cavity. Navigation and positioning: US guidance alone provided intuitive and very accurate navigating and positioning of the prosthesis within the aortic valve annulus, according to the set criteria. Anatomical examination: Aortic valve prosthesis positioning met the standards described above in all cases, but with the limitations inherent to the setting of the experiment and the limited distribution of sizes of AoVs available for placement (Figs. 8 & 9) Discussion The goal of this feasibility study was twofold: the first was to document the safety of using the UCI for LV access, and most importantly, the feasibility of introducing and positioning an unmodified AoV prosthesis. These data were critical before embarking on constructing the comprehensive technology, already designed, to make aortic valve implantation via this access safe, simple and practical. Among the multiple issues raised by this novel access, the study focused on four issues: the use and implantation of the UCI; the creation of a clean apical port access; the navigating and positioning of the aortic valve prosthesis, and US image-guidance. UCI: The UCI was designed as an air-lock proved most effective in particular when used on low pressure cavities like the right atrium. The high pressure in the left ventricle, combined with le proximal end of the UCI always above the LV port access provide ideal condition for avoiding air embolism. The use of U-shaped sutured pledgetted to attach the UCI proved safe, but the skirt was too bulky, encompassing a large segment of the LV apex. This lead to replacement of the semi-rigid skirt with an extensible vascular–type fabric that can be securely attached using 2-0 Prolene® running sutures. Running suture proved effective and less damaging to the 11 myocardium. This modification will facilitate the closing of the LV apex using conventional techniques under the safety of the UCI., leaving less foreign, while taking the long term view of facilitating re-intervention via the same access: a reality that is offered by the current development of tissue valve prostheses where only the replacement of the “tissue valve” is performed while leaving the anchored rim in place (ValveXchange, Inc. Colorado USA). In the long term, this possibility may become an incentive to develop such a feature for current prostheses. The Punch tool was useful in documenting the feasibility of introducing and positioning an AoV prosthesis. However, the use of a trocar to first penetrate the LV cavity did not produce a clean and clear cylindrical cut of the myocardial. Thus we designed a new tool that reliably excises a clean cut cylinder, but without the need for a trocar. We are also working on modifying the geometry of the LV port access, for facilitating closing of the port using conventional techniques. Introduction of the AoV through the LV port access. Although there was no evidence of the prosthesis damaging the port access and releasing a fragment of myocardium, we felt that the passage of the valve through the port needs improvement in two ways: 1) modification of the punch tool to obtain a clean circular ventricular excision, as mentioned above, and 2) transformation of the valve holder into a comprehensive valve implantor with special features addressing the need for protection of the prosthesis during its passage through the LV port, the LV outflow tract and the aortic annulus. Positioning the conventional unmodified AoV prosthesis, designed for trans-aortic retrograde implantation, was a challenging but valid test, as the prosthesis did not have a rim that could be easily applied against the AoV annulus, in a fashion similar to that by which the 12 antegrade mitral valve prosthesis is implanted through the left atrial appendage via the UCI in the pig 23. Despite these difficulties, the prosthesis was adequately positioned. These experiments confirmed that prostheses can retain their critical features, preserving their current qualities of longevity and functionality. The sole modification needs to be a new attachment rim and anchoring system, taking into consideration the issues raised by the new antegrade access. US image guidance: TEE guidance was very effective and accurate for positioning the aortic prosthesis, similar to our experience with positioning a mitral prosthesis via the UCI 23, 75 . However, anchoring of the prosthesis will require accurate and precise positioning real-time US guidance with augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) displayed on a single screen (Atamai Viewer; http:// www.atamai.com) 48 . Our experience with such imaging makes us confident that such a user-friendly guiding system can be designed for AoV prosthesis implantation, as well as with newly designed tools and devices 48, 49, 51, 53, 57, 69-75. Since the beginning of our project, our goal was to eliminate the need for fluoroscopic image-guidance on the following arguments: 1) Fluoroscopic guidance should be used only when there is no other safe image guidance modality available, since there is no safe irradiation exposure77-81. As mentioned above, we have document that US guidance augmented with virtual reality is far superior to fluoroscopic imaging. 2) Intraoperative use of contrast material can alter renal function and cause severe postoperative renal failure; associated with significant morbidity. 3) The of X-ray platform is the cause of major hindrance during surgery, and requires expensive hybrid operative rooms, those expensive requirements may prevent the dissemination of a better less invasive option that aims at reducing side-effects and cost. The 3D TEE guidance may prove an ideal and practical guidance. 13 Limitations and further issues: The use of a normal heart pig model is a significant limitation. Model of calcified aortic valve stenosis have been described in small animals but are not valid model for testing new technologies 82-86 . However, normal heart testing is a necessary first step in term of feasibility, since, if the technique cannot be under those conditions, it must have severe flaws and require dramatic revision. An experimental feasibility study is, by nature, limited, since all the issues cannot be addressed. In this study, we did not address the parietal access route, anchoring technologies or concerns with hemodynamic instability during implantation and its treatment. The goal of these animal experiments was to test feasibilities and provide a rationale to develop adjunct technology. Changing the delivery system of any intervention requires revisiting the other components of the intervention 87, 88: in particular the tools delivering the therapy on target. In that regard, this feasibility study has been productive. We have identify a list of adverse events that must be controlled and prevented to make that access safe and versatile, and design satisfactory responses regarding : maintaining normal hemodynamics, preventing damage to the prosthesis, atraumatic progression the prosthesis to avoid collateral damage to mitral valve, conduction system, coronary arteries. Optimal positioning before anchoring, a anchoring system that can allow deanchoring for improved positioning, possibility to switch prosthesis during primary implant or long term replacement. Integration of all these features must fit into a user-friendly tool that can be manipulated within the confine environment of the left ventricular outflow tract. Conclusions and Further Developments The new technologies will be designed to improve safety and versatility and make the new approach practical and easy to learn and master. 14 Based on our experience with this pilot study, we anticipate this new access will offer, with minimal risk, state-of-the-art aortic valve replacement, not only to high risk patients, but to the entire spectrum of patients with a need for replacement, including those with low risk, in whom early replacement may equal a cure. 15 Acknowledgments: The authors express their appreciation to Sheri vanLingen and Karen Siroen for assistance with animal surgery and Dave Harrison and Dave Browning for assistance with the technology. 16 Reference List 1. Bailey CP, O'Neill TJ, Glover RP, Jamison WL, Ramirez HP. Surgical repair of mitral insufficiency. Dis Chest 1951;19:125-37. 2. Bailey CP, Glover RP, O'Neill TJ. The surgery of mitral stenosis. J Thorac Surg 1950;19:16-49, illust. 3. Glover RP, Bailey CP, O'Neill TJ, Downing DF, Wells CR. The direct intracardiac relief of pulmonary stenosis in the tetralogy of Fallot. J Thorac Surg 1952;23:14-41. 4. Harken DE, Black H. Improved valvuloplasty for mitral stenosis, with a discussion of multivalvular disease. N Engl J Med 1955;253:669-78. 5. Harken DE, Dexter L, Ellis LB, Farrand RE, Dickson JFI. The surgery of mitral stenosis. III. Finger-fracture valvuloplasty. Ann Surg 1951;134:722-42. 6. Gibbon JHJ. Application of a mechanical heart and lung apparatus to cardiac surgery. Minn Med 1954;37:171-85. 7. Kirklin JW, Dushane JW, Patrick RT, Donald DE, Hetzel PS, Harshbarger HG, et al. Intracardiac surgery with the aid of a mechanical pump-oxygenator system (gibbon type): report of eight cases. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1955;30:201-6. 8. Cooley DA. A tribute to C. Walton Lillehei, the "Father of open heart surgery". Tex Heart Inst J 1999;26:165-6. 9. Lillehei CW, Dewall RA, Read RC, Warden HE, Varco RL. Direct vision intracardiac surgery in man using a simple, disposable artificial oxygenator. Dis Chest 1956;29:1-8. 10. Lillehei CW, Cohen M, Warden HE, Ziegler NR, Varco RL. The results of direct vision closure of ventricular septal defects in eight patients by means of controlled cross circulation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1955;101:446-66. 11. Guiraudon GM. Surgical treatment of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: a "retrospectroscopic" view. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:1254-61. 12. Guiraudon GM, Klein GJ, Sharma AD, Milstein S, McLellan DG. Closed-heart technique for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: further experience and potential limitations. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1986;42:651-7. 13. Guiraudon GM, Klein GJ, Sharma AD, Jones DL, McLellan DG. Surgery for WolffParkinson-White syndrome: further experience with an epicardial approach. Circulation 1986;74:525-9. 17 14. Guiraudon GM, Klein GJ, Gulamhusein S, Jones DL, Yee R, Perkins DG, et al. Surgical repair of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: a new closed-heart technique. Ann Thorac Surg 1984;37:67-71. 15. Klein GJ, Guiraudon GM, Sharma AD, Milstein S. Demonstration of macroreentry and feasibility of operative therapy in the common type of atrial flutter. Am J Cardiol 1986;57:587-91. 16. Boyd WD, Kiaii B, Kodera K, Rayman R, bu-Khudair W, Fazel S, et al. Early experience with robotically assisted internal thoracic artery harvest. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2002;12:52-7. 17. Boyd WD, Desai ND, Kiaii B, Rayman R, Menkis AH, McKenzie FN, et al. A comparison of robot-assisted versus manually constructed endoscopic coronary anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:839-42. 18. Chiu AM, Dey D, Drangova M, Boyd WD, Peters TM. 3-D image guidance for minimally invasive robotic coronary artery bypass. Heart Surg Forum 2000;3:224-31. 19. Novick RJ, Fox SA, Kiaii BB, Stitt LW, Rayman R, Kodera K, et al. Analysis of the learning curve in telerobotic, beating heart coronary artery bypass grafting: a 90 patient experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:749-53. 20. Guiraudon GM. Universal Cardiac Introducer. In: 10/736786 ed. United States of America, 2005. 21. Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Bainbridge D, Peters TM. The Universal Cardiac Introducer® for Off-pump, Closed, Beating, Intracardiac Surgery: Proof of Concept. In press 2008. Le Journal de Chirurgie Thoracique et CardioVasculaire 2008;12:28-34. 22. Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Skanes AC, Bainbridge D, Guiraudon CM, Jensen SM, et al. En bloc exclusion of the pulmonary vein region in the pig using off pump, beating, intra-cardiac surgery: a pilot study of minimally invasive surgery for atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:1417-23. 23. Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Baindridge D, Peters TM. Mitral valve implantation using offpump closed beating intracardiac surgery: a feasibility study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2007;6:603-7. 24. Guiraudon.G.M., Jones DL, Bainbridge D, Moore J, Wedlake C, Linte C, et al. Off Pump, Atrial Septal Defect Closure Using the Universal Cardiac Introducer® (UCI). Creation and Closure of an ASD in a Porcine Model: Access and Surgical Technique. Innovations 2009;4:20-6. 18 25. Khan SS, Trento A, DeRobertis M, Kass RM, Sandhu M, Czer LS, et al. Twenty-year comparison of tissue and mechanical valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;122:257-69. 26. Guiraudon GM, Thakur RK, Klein GJ, Yee R, Guiraudon CM, Sharma A. Encircling endocardial cryoablation for ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction: experience with 33 patients. Am Heart J 1994;128:982-9. 27. Guiraudon GM, Fontaine G, Frank R, Escande G, Etievent P, Cabrol C. Encircling endocardial ventriculotomy: a new surgical treatment for life-threatening ventricular tachycardias resistant to medical treatment following myocardial infarction. Ann Thorac Surg 1978;26:438-44. 28. Moss AJ. Background, outcome, and clinical implications of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT). Am J Cardiol 1997;80:28F-32F. 29. Aazami MH, Salehi M. The Arantius nodule: a 'stress-decreasing effect'. J Heart Valve Dis 2005;14:565-6. 30. Al QH, Momenah T, El OR, Al RA, Tageldin M, Al FY. Minimally invasive transventricular implantation of pulmonary xenograft. J Card Surg 2008;23:33940. 31. Antunes MJ. Percutaneous aortic valve implantation. The demise of classical aortic valve replacement? Eur Heart J 2008;29:1339-41. 32. Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Grube E. Percutaneous implantation of the first repositionable aortic valve prosthesis in a patient with severe aortic stenosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2008;71:579-84. 33. Cohn LH, Narayanasamy N. Aortic valve replacement in elderly patients: what are the limits? Curr Opin Cardiol %2007 Mar ;22 (2):92 -5. 34. Cohn WE. Percutaneous valve interventions: where we are and where we are headed. Am Heart Hosp J 2006;4:186-91. 35. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, Bauer F, Agatiello C, Sebagh L, et al. Early experience with percutaneous transcatheter implantation of heart valve prosthesis for the treatment of end-stage inoperable patients with calcific aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:698-703. 36. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, Bauer F, Agatiello C, Nercolini D, et al. Treatment of calcific aortic stenosis with the percutaneous heart valve: mid-term follow-up from the initial feasibility studies: the French experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1214-23. 37. Jamieson WR. Advanced technologies for cardiac valvular replacement, transcatheter innovations and reconstructive surgery. Surg Technol Int 2006;15:149-87. 19 38. Lichtenstein SV, Cheung A, Ye J, Thompson CR, Carere RG, Pasupati S, et al. Transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation in humans: initial clinical experience. Circulation 2006;114:591-6. 39. Vahanian A, Alfieri OR, Al-Attar N, Antunes MJ, Bax J, Cormier B, et al. Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:1-8. 40. Walther T, Dewey T, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Doss M, Hambrecht R, Schuler G, et al. Transapical approach for sutureless stent-fixed aortic valve implantation: experimental results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:703-8. 41. Walther T, Falk V, Dewey T, Kempfert J, Emrich F, Pfannmuller B, et al. Valve-in-avalve concept for transcatheter minimally invasive repeat xenograft implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:56-60. 42. Walther T, Simon P, Dewey T, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Falk V, Kasimir MT, et al. Transapical minimally invasive aortic valve implantation: multicenter experience. Circulation 2007;116:I240-I245. 43. Walther T, Falk V, Borger MA, Kempfert J, Ender J, Linke A, et al. Transapical aortic valve implantation in patients requiring redo surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009. 44. Wilson K, Guiraudon G, Jones D, Linte CA, Wedlake C, Moore J, et al. Dynamic cardiac mapping on patient-specific cardiac models. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2008;11:967-74. 45. Zhang Q, Huang X, Eagleson R, Guiraudon G, Peters T. Real-time dynamic display of registered 4D cardiac MR and ultrasound images using a GPU. In. Proceedings of the SPIE International Symposium on Medical Imaging 2007. San Diego, CA. . 2007., 2007:61412T. 46. Zhong H., Wachowiak MP, Peters T. Adaptive Finite Element Technique for Cutting in Surgical Simulation. . In: Robert L.Galloway Jr KRC, ed. 5744(Medical Imaging 2005:Visualization, Image-guided Procedures, and Display). Bellingham, WA, SPIE, 2005:604-611. 47. Bainbridge D, Jones DL, Guiraudon GM, Peters TM. Ultrasound image and augmented reality guidance for off-pump, closed, beating, intracardiac surgery. Artif Organs 2008;32:840-5. 48. Guiraudon GM, Bainbridge D, Moore J, Wedlake C, JD, Peters TM. Augmented reality for closed, beating, intracardiac interventions. In. Proceedings collection-CD International Workshop on Augmented Environments for Medical Imaging and 20 Computer Aided Surgery. AMI-ARCS 06, 2006 . MICCAI 2006, Copenhagen , denmark., 2006:AMI-ARCS 06, 2006. 49. Guiraudon GM, Wierzbicki M, Moore J, Jones DL, Wedlake C, Bainbridge D, et al. Virtual Reality Guidance for Mitral Valve Implantation on the Off-Pump, Closed, Beating Heart: Tracked Virtual Mitral Valve Annulus as a Marker of Recalibration Necessitated by Intraoperative Heart Displacement. Can J cardiol 2007;23:213C-4C. 50. Huang H, Hill NA, Ren J, Guiraudon G, Peters TM. Dynamic multi-modality imaging of 3D echocardiography and MRI. Can J Cardiol 2005;In Press(Abstract). 51. Huang X, Hill N, Ren J, Peters T. Rapid registration of multimodal images using a reduced number of voxels. In. Proceedings of the SPIE International Symposium on Medical Imaging 2006. San Diego, CA. 2006., 2006:6141-6142. 52. Huang X, Moore J, Guiraudon G, Jones D, Bainbridge D, Ren J, et al. Dynamic 2D Ultrasound and 3D CT Image Registration of the Beating Heart. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2009. 53. Linte C, Wiles A, Moore J, Wedlake C, Guiraudon.GM., Jones DL, et al. An augmented reality environment for image-guidance of off-pump mitral valve implantation. In. Proceedings of the SPIE International Symposium on Medical Imaging 2007. San Diego, CA; 2007:6509 6522. 54. Linte CA, Wierzbicki M, Moore J, Guiraudon G, Jones DL, Peters TM. On enhancing planning and navigation of beating-heart mitral valve surgery using pre-operative cardiac models. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2007;2007:475-8. 55. Linte CA, Wierzbicki M, Moore J, Little SH, Guiraudon GM, Peters TM. Towards subject-specific models of the dynamic heart for image-guided mitral valve surgery. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2007;10:94-101. 56. Peters TM. Image-guidance for surgical procedures. Phys Med Biol 2006;51:R505-R540. 57. Peters TM. Towards subject-specific models of the dynamic heart for image-guided mitral valve surgery. In: Ayache N, Ourselin S, eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2007: 10th International ConferenceProceedings Part II. Berlin Heidelberg.: Springer-Verlag, 2007:94101. 58. Ren J, Patel RV, McIsaac KA, Guiraudon G, Peters TM. Dynamic 3-D virtual fixtures for minimally invasive beating heart procedures. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2008;27:1061-70. 21 59. Szpala S, Wierzbicki M, Guiraudon GM, Peters TM. Dynamic of an modeling for minimally-invasive cardiac surgery. SPIE Proceedings 2004. 60. Wierzbicki M, Drangova M, Guiraudon GM, Peters T. Four-dimensional modeling of the heart for image guidance of minimally invasive cardiac surgeries. Proceedings of the SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering 2004;5367:30211. 61. Wierzbicki M, Drangova M, Guiraudon G, Peters T. Validation of dynamic heart models obtained using non-linear registration for virtual reality training, planning, and guidance of minimally invasive cardiac surgeries. Med Image Anal 2004;8:387401. 62. Wilson K, Guiraudon G, Jones D, Peters TM. 4D shape registration for dynamic electrophysiological cardiac mapping. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2006;9:520-7. 63. Zhang X, Hill NA, Ren J, Guiraudon G, Boughner D, Peters TM. Dynamic Multimodality imaging of 3D echocardiography and MRI. Can J Cardiol 2005; 2005;21:127 C. 64. Zspala S, Wierzbicki., Guiraudon GM, Peters TM. Real-time fusion of endoscopic views with dynamic 3D cardiac images: A phantom study. . IEEE Trans Medical Imaging 2005. 65. Swindle MM. Swine in the laboratory. CRC Press. Taylor & Francis Group. Boca Raton. London. New York., 2007. 66. McAlpine WA. Heart and Coronary Arteries. Springer-Verlag. New York, Heidelberg, 1975. 67. Wilcox BR, Amderson RH. Surgical Anatomy of the Heart. Gower Medical Publishing. London. New York, 1992. 68. Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Skanes AC., Bainbridge D, Guiraudon CM, Jensen S, et al. En Bloc Exclusion of the Pulmonary Vein Region in the Pig Using Off Pump, Beating, Intra-Cardiac Surgery: A Pilot Study of Minimally-Invasive Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation. I. The Ann thorac Surg 2005;80:1417-23. 69. Moore J, Guiraudon G, Jones D, Hill N, Wiles A, Bainbridge D, et al. 2D ultrasound augmented by virtual tools for guidance of interventional procedures. Stud Health Technol Inform 2007;125:322-7. 70. Huang X, Hill NA, Ren J, Guiraudon G, Boughner D, Peters TM. Dynamic 3D ultrasound and MR image registration of the beating heart. In: Duncan J, Gerig G, eds. Heidelberg, Berlin. Germany: Spriger verlag, 2005:171-178. 22 71. Bainbridge D, Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Moore J, Wedlake C, Linte C, et al. Evaluation of image guidance as a substitute to direct vision for off pump atrial septal defect closure using the universal cardiac introducer®. Can J cardiol 2007;23:213C. 72. Peters TM. Image-guidance for surgical procedures. Phys Med Biol 2006;51:R505-R540. 73. Linte CA, Wierzbicki M, Moore J., Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Peters T.M. On Enhancing Planning and Navigation of Beating-Heart Mitral Valve Surgery using Pre-operative Cardiac Models. In. Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS - Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society., 2007:475-478. 74. Linte CA, Wierzbicki M, Moore J, Little SH, Guiraudon GM, Peters TM. Towards subject-specific models of the dynamic heart for image-guided mitral valve surgery. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2007;10:94-101. 75. Guiraudon GM, Linte C, Wierzbicki M, Moore J, Jones DL, Wedlake C, et al. Virtual reality guidance for mitral valve implantation on the off-pump, closed, beating heart: tracked virtual mitral valve annulus as a marker of recalibration necessitated bye intraoperative heart displacement. Can J cardiol 2007;23:213c4C. 76. Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Skanes A.C., Bainbridge D, Guiraudon CM, Jensen S, et al. En Bloc Exclusion of the Pulmonary Vein Region in the Pig Using Off Pump, Beating, Intra-Cardiac Surgery: A Pilot Study of Minimally-Invasive Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:1417-23. 77. Archer BR. Radiation management and credentialing of fluoroscopy users. Pediatr Radiol 2006;36:182-4. 78. Detorie N, Mahesh M, Schueler BA. Reducing occupational exposure from fluoroscopy. J Am Coll Radiol 2007;4:335-57. 79. Strauss KJ, Kaste SC. The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) concept in pediatric interventional and fluoroscopic imaging: striving to keep radiation doses as low as possible during fluoroscopy of pediatric patients--a white paper executive summary. Radiology 2006;240:621-2. 80. Wierzbicki M, Guiraudon GM, Jones DL, Peters T. Dose reduction for cardiac CT using a registration-based approach. Med Phys 2007;34:1884-95. 81. Zabala LM, Schmitz ML, Ullah S, Watkins WB, Tuzcu V. Electrophysiology studies without fluoroscopy. Anesth Analg 2006;103:780. 82. Cimini M, Boughner DR, Ronald JA, Aldington L, Rogers KA. Development of aortic valve sclerosis in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis: an immunohistochemical and histological study. J Heart Valve Dis 2005;14:365-75. 23 83. Cuniberti LA, Stutzbach PG, Guevara E, Yannarelli GG, Laguens RP, Favaloro RR. Development of mild aortic valve stenosis in a rabbit model of hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2303-9. 84. Drolet MC, Arsenault M, Couet J. Experimental aortic valve stenosis in rabbits. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1211-7. 85. Hekimian G, Passefort S, Louedec L, Houard X, Jacob MP, Vahanian A, et al. Highcholesterol + vitamin D2 regimen: a questionable in-vivo experimental model of aortic valve stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis 2009;18:152-8. 86. Rajamannan NM. Calcific aortic stenosis: lessons learned from experimental and clinical studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:162-8. 87. Guiraudon GM. Surgery without interventions? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998;21:2160-5. 88. Guiraudon GM. Musing while cutting. J Card Surg 1998;13:156-62. 24 Figure Legends Figure 1: Diagram of the Universal Cardiac Introducer ® (UCI) used for placement of the aortic valve prosthesis. The port opening is controlled by the attachment cuff. Attached to the cuff is the introductory chamber which contains various sleeves for introduction of the valve and holder, and additional sleeves which can be used for tools and devices, infusion of fluids or monitoring of the pressure in the chamber heart. Figure 2: Photographs of the punching tool. A. The full length of the tool with partial extrusion of the trocar equipped with a cutting blade, and a flat base used as an anvil for the circular blade and trapping the excised myocardium within the cylinder. B. Close-up of the cutting blades on the trocar. Figure 3: Photograph of bicuspid prosthetic aortic valve secured to the custom valve holder with its handle. Figure 4: Operative view showing the porcine left ventricular apex, with its conic shape well exposed via a median sternotomy. Figure 5: Schematic representation of implantation of the UCI and Punch tool. A: The attachment cuff is being attached to the left ventricular (LV) apex. B: The cuff is attached to the LV apex. C: Attachment of the introductory chamber. D: Creation of the LV port access via the UCI. E: Comparison of the size of the prosthesis and the punch tool diameters. Figure 6: Punch tool and LV port access: A. Photograph of the circular tissue trapped along the shaft of the trocar between the anvil and the circular cutting blade. B. Circular tissue removed from the punching tool. C. Photo of the heart in situ after exsanguination with the valve holder against the circular opening. D. The circular opening into the ventricle in the 25 excised heart. Post mortem, due to the slanted cut in the pig, the LV port access becomes conical. Figure 7: Ultrasound image Guidance: the figure represents the various phases of progression of the prosthesis along the LV outflow tract into the aortic valve annulus. Panel A shows an ultrasound cross section of the left heart. Panel B shows the echoes of the holder between the paired echoes of the prosthetic rim. Panel C the prosthesis is within the aortic valve annulus. Panel D is an equivalent anterior view of an excised heart specimen with the anterior walls of the left and right ventricles removed. The holder is positioned with the prosthetic aortic valve (AoV) within the outflow tract of the left ventricle (LV) against the native aortic annulus. Figure 8: Post mortem photographic view of the prosthesis: The left ventricle (LV) has been opened via the LV port along the outflow tract. The sub-aortic channel has been preserved to show the positioning of the prosthesis. Figure 9: Photograph of the retrograde view via the ascending aorta to show the position of the bicuspid valve seated in the aortic outflow track of the excised heart. 26 Figure 1 Figure 2 27 Figure 3 28 Figure 4 29 Figure 5 30 Figure 6 31 Figure 7 Figure 8 32 Figure 9 33