* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Encylopedia Britannica Student Edition Introduction to International

Internationalism (politics) wikipedia , lookup

Predictions of the dissolution of the Soviet Union wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the Cold War wikipedia , lookup

New world order (politics) wikipedia , lookup

Multinational state wikipedia , lookup

Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty wikipedia , lookup

Aftermath of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Culture during the Cold War wikipedia , lookup

Decolonization wikipedia , lookup

United States non-interventionism wikipedia , lookup

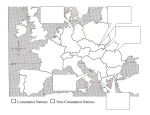

international relations Britannica Student Encyclopedia The world of the early 21st century is a global community of nations, all of which coexist in some measure of political and economic interdependence. By means of rapid communication systems— radio, television, and computers—much of what happens in one place is quickly known almost everywhere else. The speed of transportation in modern aircraft also makes it possible for people to get around the globe in hours instead of days or weeks. The modern world community was not, however, created by communications and transportation alone. The present global situation is new to history and owes its origins to a variety of factors that include the great conflict of World War II, the postwar breakdown of colonial empires, the long rivalry between the former Soviet Union and the United States, and the fast-growing economic interrelationships of all nations, large and small. Origins of the Global Community Ever since there have been organized political entities variously called states, kingdoms, nations, and countries, there have been relations between them based on economics (trade) and on politics (war, territorial expansion, and colonization). International relations today encompasses the foreign policies of the more than 200 nation-states and dependencies and the regional blocs in which some are associated. The nation-state was invented in Europe, not by design, but out of a desire to resolve political conflicts that had gone on for centuries. By the end of the Middle Ages there had emerged several nations with the distinct political identity they have today: France, Britain, and Spain. In addition there was the slowly dying Holy Roman Empire, generally under the control of the House of Hapsburg. To the east Russia was a growing political power; and in the 17th century Prussia began to emerge as the dominant force among the Germanic principalities within the old Holy Roman Empire. (See also Holy Roman Empire; Prussia; Russia.) All of these states were monarchies, and each of them, given the chance, would have tried to exert control over the rest. France, in fact, did make a remarkable attempt during the Napoleonic wars (see Napoleon I). In the settlement made at Vienna after Napoleon's final defeat, Europe was given political stability that endured for nearly a century. In the late 19th century Germany and Italy were each unified. The only empires remaining on the Continent were the old Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire, and Austria-Hungary. They controlled much of eastern Europe. The Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary were creaking with old age, and the subject peoples within them aspired to gain their independence. The idea of the nation-state had triumphed in Europe. What it entailed was that each state exist within its own prescribed boundaries, with its own government, its own economy, and its own culture. The models for this idea were the United States and France, both of which had, within a short period, experienced unprecedented revolutions. The political ideals that inspired the American Revolution were European in origin. The infectious principle of civil government that sped through the Americas was appreciated in Europe by peoples whose aspirations were the same. France became the first nation of Europe to overthrow its monarchy; and in doing so, it soon found all the rest of Europe arrayed against it. The French people had made their own government, and for the first time in world history, a people realized that it and the nation were one. France was no longer the monarch and his subjects, it was the people themselves defending their revolution. And at the time, the revolution and the country were the same. In the wholehearted devotion of the French to their patrie—their country—patriotism was born. This was a new kind of loyalty, one that soon became a standard ingredient of the idea of the nation. But the course of empire was by no means finished. No sooner had the states of Europe consolidated their political power than they set out on the trail of conquest. The conquests were no longer in Europe; they were on other continents. Spain, Portugal, France, Britain, Russia, Sweden, and the Netherlands had already colonized the New World (see America, discovery and colonization of). In a period of about 300 years, European nations established colonies around the globe. All of Africa, except for Ethiopia and Liberia, was under colonial rule. The Indian subcontinent belonged, for the most part, to Britain. France had subdued much of Indochina. Holland dominated the East Indies. Russia moved eastward into Siberia and beyond. China was in the process of disintegration and the object of imperial rivalries by outside powers. In all the non-Western world Japan stood alone in being able to resist the encroachment of European states, and it did so only by adopting their organizational and technological skills. By the early 20th century Japan was creating its own imperial designs in the Far East. It was this pursuit of empire by the nations of Europe that prevented so many parts of the world from gaining political independence for so long (see colonialism and imperialism). The End of Empire Without intending it, the imperial powers of Europe created the foundations of the global community. The colonial conquests created international units—the British Empire, the Belgian Empire, the French Empire, the Spanish Empire, and so forth—with centers of power in London, Brussels, Paris, or Madrid. Within the colonies themselves, centers of power developed that brought the peoples of a colony together in a search for political and ethnic identity. Once the reins of imperial rule were weakened, demands for local autonomy were bound to be met. The two world wars of the 20th century ended the age of empire. After the first war AustriaHungary was broken up by the settlement at Versailles (see World War I). Within a few years the tottering Ottoman Empire had ceased to exist and modern Turkey emerged. Germany, as a loser in the war, lost its colonies. Two of the victors in the war, France and Great Britain, maintained their overseas empires intact, however. Belgium, Portugal, and The Netherlands retained their holdings; and after the war Italy sought to aggrandize itself by taking control of Libya and invading Ethiopia. Russia, after the Revolution of 1917, began to extend its empire to form what became the Soviet Union. Japan also began to assert itself in the Far East by taking over Manchuria in 1931 and invading China in 1937. By the late 1930s Japan had visions of dominating the whole Far East in a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” It seemed, for a time, that the empires of the world were simply rearranging themselves. The illusion was a mistake; by the end of World War II all the imperial structures of the world—except for the Soviet Union—lay in ruins. Within a few years, the British Empire had given way to the Commonwealth of Nations. France strove determinedly for a time to keep its holdings in Indochina and Africa, but they, too, were soon gone (see Algeria; Commonwealth; Indochina; Vietnam War). One by one, the colonies of Africa became independent nations. Old monarchies in eastern Europe and the Middle East underwent revolutions and became republics. China's revolution led to the establishment of the world's largest Communist state in 1949. India, independent from Great Britain, became the world's most populous democracy. Japan was reduced to its multi-island homeland. By the 21st century the world had become a community of more than 190 independent nations, a situation that had never existed before. Some of these nations were huge—Russia, China, Canada, and the United States—while others were as small as Monaco on the Mediterranean coast. The old empires were gone, but a new factor arose to offset them: hegemony, or dominant spheres of influence. Most of Europe was destroyed both physically and economically by World War II. Even Great Britain, among the victors, was on the brink of financial ruin. Japan also was devastated. The old colonial societies had not yet begun to throw off their imperial shackles. Only the two superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, were left to aid in rebuilding the world economy. The World Community, 1945–90 Unfortunately for the world community, the two superpowers emerged from the war in a state of mutual distrust and hostility. Each was wary of the other's intents. The United States was concerned that the Soviet Union would expand its influence by incorporating eastern Europe into its political system, and this is, in fact, what happened. The presence of the Soviet Army in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, East Germany, and Bulgaria resulted in these nations' becoming Soviet satellites—that is, they fell within the Soviet sphere of influence. The Soviet Union itself, however, was left in ruins by the war. That country was fearful that the United States, which at the time was the only nation possessing atomic weapons, would attempt to destroy the Soviet system. Out of this situation of mutual superpower hostility there developed the Cold War, with each of the two nations seeking to enlarge its sphere of influence around the world by forming alliances, offering foreign aid, selling massive quantities of arms, and undermining the governments of smaller nations. The Cold War never became a hot war between the superpowers, probably only because of the awesome threat of nuclear weapons. (See also Cold War.) U.S. anxieties over Soviet power were greatly increased by the success of the Communist revolution in China. After Mao Zedong (also spelled Mao Tse-tung) and his followers came to power in 1949, evincing great hostility toward the United States, there was a general fear that the might of international Communism would be impossible to contain. The Cold War, while perhaps the dominant feature of international relations in the late 20th century, was by no means the only important development. All over the world, former colonies were gaining independence. A new world structure was emerging, because these new nations were demanding a role in international politics and were slowly becoming integrated into a growing world economy. Revolutions, some homegrown and some fomented from the outside, were going on in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. And the United States lost its monopoly on nuclear weapons; the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, and others joined the international “atomic club.” With the new political order that emerged in the 1950s came a new terminology. A common way of classifying countries at the time was to identify them with one of four fairly distinct groups, or “worlds.” The First World consisted of the United States and its allies, primarily western Europe and Japan. The Second World denoted the Soviet Union and its satellites in eastern Europe. The term Third World was coined in French (tiers monde) in 1952 to describe a group of countries that chose to stay out of the Cold War rivalry. Among these nations were Yugoslavia, Egypt, India, Ghana, and Indonesia. By the mid-1950s the meaning of the term had broadened to refer to all nonindustrialized or developing countries. The meaning of Third World, therefore, had changed to an economic one. The term Fourth World was applied to countries that were desperately poor. The Third World The number of poverty-stricken and underdeveloped nations was great in the 1950s. Many were just emerging from colonialism. Others had been badly governed for decades. After 1960 the number of worst-case economies diminished. Africa remained, for the most part, underdeveloped. Parts of Latin America, however, experienced some dramatic changes as dictatorships gave way to democracies. Mexico proved to be one of the economic miracles of the late 20th century. Brazil, Chile, and Argentina, after decades of misrule, began making significant progress after 1985. Many areas of Southeast Asia experienced rapid economic development. Even China, long considered the largest Third World society, experienced striking economic growth in its southern regions. The Arab states of the Middle East prospered if they had petroleum reserves. In the early years of the Cold War, the leaders of the Third World realized that, acting independently, they could have little impact in international relations. To remedy this, they organized. In April 1955 at Bandung, Indonesia, delegates from 29 countries met in a conference organized by Indonesia, India, Burma (now Myanmar), Pakistan, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). These delegates formed an association of nations not aligned with either of the two superpowers, though they tended to identify more with the Soviet Union and China than with the democracies. This policy of nonalignment, or neutralism, was strengthened and advanced by President Tito of Yugoslavia. In September 1961 he hosted a conference of nonaligned nations in Belgrade. The conference, convened by India's Jawaharlal Nehru, Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Tito, denounced colonialism, demanded an end to armed action against dependent peoples, endorsed the Algerians in their war for independence from France, and called for a policy of perpetual neutralism between the great powers. As Cold War tensions eased in the 1980s, the nonaligned movement began fading. Many member countries were undergoing economic transformation and wanted to strengthen ties to the industrialized regions—the United States, Japan, and western Europe. The Industrial North At the end of World War II, the United States stood alone in industrial might. All of Europe and Japan had been devastated by the war. The Soviet Union was an economic shambles. To rebuild the West and Japan, the United States launched a massive foreign aid program called the Marshall Plan, named after George C. Marshall, who proposed the plan in 1947. During the four-year life of the plan, western Europe was provided with more than 17 billion dollars in aid for economic reconstruction. Japan also was assisted in rebuilding. The result of these efforts was an era of unprecedented affluence in the industrialized societies. After the war-torn nations got back on their feet, however, the efforts also produced an era of economic rivalry. As long as the prosperity lasted, the rivalry was little noticed. But when the oilproducing countries of the Middle East instituted marked increases in prices during the 1970s the economic scene darkened. A worldwide recession, coupled with perpetual inflation, set in. By the early 1980s the solidarity of the industrial West had weakened as each nation tried to maintain economic stability amid unfavorable conditions. What did keep them together was their distrust of the Soviet Union. The Eastern bloc nations, led by the Soviet Union, also faced the task of rebuilding after the war. The process took longer because they chose not to be recipients of Marshall Plan funds. And they had been poorer and less industrialized than the nations of western Europe before the war as well. Worlds in Turmoil The conclusion of World War II ended the drive by Germany, Italy, and Japan for world domination; but the seed of smaller conflicts had already been planted. Even as Japan was evacuating Southeast Asia, Vietnam, under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, was planning to get rid of French colonialism for good. Vietnam's effort resulted in a long war, a conflict that ended in 1975 with a Communist victory. Instead of rebuilding the region, however, the victors went on to fight among themselves and to leave Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in desolation (see Vietnam War). The Vietnam War was only one of several conflicts that erupted out of the Cold War. Soviet and U.S. power confronted each other in several places, especially in Europe and Korea. The settlement in Europe after World War II not only divided the continent into two hostile factions, but it also divided Germany into two countries and Berlin into two cities. This was a source of strife in 1948, when the Soviets instituted a blockade of West Berlin, geographically in the heart of Sovietoccupied territory. An airlift of U.S. and British goods and services into West Berlin thwarted the blockade, which was abandoned in mid-1949. The hostilities, though, endured until 1989 (see Berlin; Korean War). In Cuba, forces led by Fidel Castro staged a successful Communist revolution in the late 1950s. Cuba then became a Soviet dependency. In 1962 the threat of nuclear war escalated when the Soviet Union placed guided missiles aimed at the United States in Cuba. U.S. President John F. Kennedy blockaded Cuba to prevent more missiles from entering the country, and eventually Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev ordered the removal of the weapons. In the early 1980s much of Central America was torn by conflict, with guerrillas supplied by the Soviet Union and Cuba fighting soldiers armed and trained by the United States. Not all of the global trouble spots owed their origin to the Cold War, though most of them were affected by it. One of the most persistent areas of conflict since the founding of the State of Israel in 1948 has been the Middle East. There has been relentless hostility, and several wars were fought between the Arab states and Israel (see Arab-Israeli wars). The Cold War injected itself into the Middle East, when the Soviet Union started supplying some Arab states with weapons; Syria and Iraq were notable examples. Other Muslim nations—Saudi Arabia and Jordan among them—tried to maintain neutrality in the Cold War. New World Order With a suddenness that no one could have predicted, the Cold War ended in 1990. The most striking symbol of its end was the opening of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and its subsequent destruction. The end of the Cold War resulted from the demise of Communism in eastern Europe and then in the Soviet Union itself. This event surprised the world, but it had been in the making for a long time. The process began on March 6, 1953, the day after the death of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. The totalitarian state that he had ruled for about 30 years was suddenly in the hands of men who were relieved at his departure and unwilling to rule with his style of brutality. In addition, by the end of the decade relations with China had worsened significantly. There was a genuine break between the two countries in the early 1960s. The plan for international Communism was shattered. While maintaining a sure hold over eastern Europe, the Soviet Union attempted to gain better relationships with the West, particularly the United States. The economies of the Communist societies worsened. The persistent shortages of consumer goods, even food, frustrated the citizens of these countries. By the early 1980s it was apparent to the rulers of the Soviet Union that real reform was needed if their country was going to survive. In 1985 Mikhail Gorbachev became president of the country and he attempted to reform the seriously ailing economy. Although he intended to perpetuate control by the Communist party, once he allowed freedom of speech, through a policy called glasnost, the people rejected Communism and demanded democracy. (See also glasnost and perestroika; Gorbachev, Mikhail.) Gorbachev also made it clear to the leaders of eastern European Communist states that Soviet troops would no longer be available to keep them in power. This policy triggered the rapid collapse of Communist regimes in all of eastern Europe. It began in Poland, spread to Hungary and Czechoslovakia, then spread to East Germany. With the breaching of the Berlin Wall, there was to be no turning back. The rest of the countries of eastern Europe abandoned Communism within a few months. By October 1990 Germany was reunited and the Warsaw Pact was dissolved. One year later the Soviet Union itself ceased to exist, and the country broke apart into several independent republics. The end of the Cold War did not signal the end of international strife. Old problems remained, but they no longer flourished under cover of East-West competition. In the Middle East, for example, the weakness of the Soviet Union after 1989 meant that states such as Iraq and Syria could no longer rely on it for weapons and support. Thus, when Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, it found itself opposed by a whole United Nations (UN) coalition of armed forces—including those of Syria (see Persian Gulf War). Hopes for peace in the Middle East were renewed in 1993, when Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasir 'Arafat signed a peace agreement that called for Palestinian self-rule to be gradually established in most of the occupied territories. In 2000, however, the peace process faltered, and violence erupted in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. U.S.- and British-led wars in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) further complicated international relations in the Middle East. In southern Europe the collapse of Communism had bred civil war in Yugoslavia. The small nation had been ruled by Tito from 1943 until 1980. His death weakened the bonds that held the six republics together, and old ethnic strifes resurfaced. Four of the Yugoslav republics seceded in 1991–92, and the country was plunged into civil war, first in Croatia and then in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Another conflict broke out in 1998–99 when an ethnic Albanian liberation organization in the Serbian province of Kosovo called for independence. The government's attempts to crush resistance in the province drew international outcry, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) bombarded the country for some 11 weeks. Yugoslavia ceased to exist in 2003 when the two remaining republics reconstituted the country as Serbia and Montenegro. In the Far East, the Chinese government rejected democracy in June 1989, when it crushed the youth demonstration in Beijing's Tiananmen Square—a rebellion that was seen worldwide on television. Yet, in spite of the regime's harshness toward the rebels, it permitted economic reforms to continue. The southern sector of China soon had one of the fastest growing and most prosperous economies in the world. Outsiders, mainly in the United States, complained about China's humanrights violations, but they were unwilling to break off relationships or impose sanctions on the world's most populous nation. The Conduct of International Relations Each nation has three foreign-policy goals: physical security—the freedom from outside attack and internal revolution; political security—the freedom to run its own affairs without outside interference; and economic stability and development—the freedom to trade in world markets and to satisfy its own population's demands for goods and services. Nations traditionally dealt with each other on a one-to-one basis or in strategic alliances in pursuing these goals. But in the complicated arena of the modern global community, it is more common to work through organizations. To meet the needs of international cooperation, a vast number of organizations of all types have been created. Organizations The most comprehensive international organization was founded in 1945—the United Nations and its many affiliates. Regional associations include the Organization of American States (1948), the African Union (founded as the Organization of African Unity in 1963), the League of Arab States (1945), and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (1967). These organizations deal with the whole range of political and economic issues in their areas. The Cold War spawned a number of regional mutual-defense alliances. The best known were NATO, formed in 1949, and the Warsaw Pact, signed in 1955. NATO was a military alliance formed to defend western Europe from the Soviet Union; the Warsaw Pact was the Soviet counteralliance. ANZUS—a security treaty between Australia, New Zealand, and the United States—was signed in 1951. The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization was formed in 1954 and disbanded in 1977. Many international and regional organizations have evolved to deal with the financial needs of the global community. There are too many to be able to list them all, but some of the leading ones include the International Monetary Fund, the European Union, the Caribbean Community, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation, the African Development Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Asian Development Bank. Foreign Policy All the complex devices and attitudes that a nation develops to use in its interactions with other nations make up its foreign policy. Policy formulation is the responsibility of specific government agencies—the United States Department of State or the British Foreign Office, for example. In the United States the direction of foreign policy is the task of the president, though in many matters he must have the approval of the United States Senate. Other agencies also contribute to formulation of policy. Among them are the National Security Council, the Department of Defense, and the Central Intelligence Agency. Since foreign policy in the early 21st century can be quite complex, other agencies may also contribute information. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, for instance, keep abreast of economic conditions in most countries and play a major role in offering foreign aid. Each national government operates worldwide through its embassies and consulates. An embassy is the highest official representation one nation maintains in another. Normal diplomacy is conducted by ambassadors and their subordinates. Consulates deal primarily with commercial issues and the protection of the economic interests of their nationals. A consul is not a diplomat and therefore cannot take up duties until the host nation grants permission. A nation has only one embassy in a given country, but it may have several consulates. (See also diplomacy.) Additional references about international relations Bloomfield, L.P. The Foreign Policy Process (Prentice, 1982). Couloumbis, T.A. Introduction to International Relations, 4th ed. (Prentice, 1990). Deutsch, K.W. Tides Among Nations (Free Press, 1979). Frankel, Joseph. International Relations in a Changing World, 4th ed. (Oxford, 1989). Hollis, Martin. Explaining and Understanding International Relations (Clarendon, 1990). Kronenwetter, Michael. The War on Terrorism (Messner, 1989). Patchen, Martin. Resolving Disputes Between Nations: Coercion or Conciliation? (Duke Univ. Press, 1988). Reynolds, P.A. An Introduction to International Relations (Longman, 1994). Thompson, K.W. The Fathers of International Thought (Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1994).