* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Evolution of Ethics in the Island of Doctor Moreau and Heart of

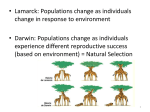

Sociocultural evolution wikipedia , lookup

Introduction to evolution wikipedia , lookup

Acceptance of evolution by religious groups wikipedia , lookup

Koinophilia wikipedia , lookup

Hindu views on evolution wikipedia , lookup

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

Catholic Church and evolution wikipedia , lookup

Saltation (biology) wikipedia , lookup

Theistic evolution wikipedia , lookup

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex wikipedia , lookup