* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Can social cognitive theory constructs explain socio

Food and drink prohibitions wikipedia , lookup

Food coloring wikipedia , lookup

Food politics wikipedia , lookup

Food studies wikipedia , lookup

Human nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Obesity and the environment wikipedia , lookup

Overeaters Anonymous wikipedia , lookup

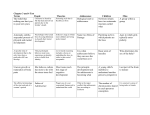

HEALTH EDUCATION RESEARCH Vol.24 no.3 2009 Pages 496–506 Advance Access publication 16 November 2008 Can social cognitive theory constructs explain socio-economic variations in adolescent eating behaviours? A mediation analysis K. Ball*, A. MacFarlane, D. Crawford, G. Savige, N. Andrianopoulos and A. Worsley Abstract Adolescents of low socio-economic position (SEP) are less likely than those of higher SEP to consume diets in line with current dietary recommendations. The reasons for these SEP variations remain poorly understood. We investigated the mechanisms underlying socioeconomic variations in adolescents’ eating behaviours using a theoretically derived explanatory model. Data were obtained from a community-based sample of 2529 adolescents aged 12–15 years, from 37 secondary schools in Victoria, Australia. Adolescents completed a webbased survey assessing their eating behaviours, self-efficacy for healthy eating, perceived importance of nutrition and health, social modelling and support and the availability of foods in the home. Parents provided details of maternal education level, which was used as an indicator of SEP. All social cognitive constructs assessed mediated socio-economic variations in at least one indicator of adolescents’ diet. Cognitive factors were the strongest mediator of socio-economic variations in fruit intakes, while for energydense snack foods and fast foods, availability of energy-dense snacks at home tended to be strong mediators. Social cognitive theory provides a useful framework for understanding socioeconomic variations in adolescent’s diet and Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition Research, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC 3125, Australia *Correspondence to: K. Ball. E-mail: [email protected] might guide public health programmes and policies focusing on improving adolescent nutrition among those experiencing socio-economic disadvantage. Introduction Nutrition during adolescence is critical for healthy development [1], yet many adolescents have diets that are not consistent with dietary guidelines for health [2, 3]. Adolescents of low socio-economic position (SEP) are at particular risk. For example, in developed countries, adolescents of lower SEP tend to consume fewer vegetables, fruits and high-fibre foods, but more high-fat foods than their counterparts of higher SEP [4–7]. Irregular meal patterns and snack consumption have also been associated with low SEP [8]. These dietary variations have been observed regardless of the indicator of SEP used. Socio-economic variations in diet are of concern since they parallel socio-economic inequalities in a range of chronic health conditions [9], and they may represent a pathway by which socio-economic disadvantage leads to poorer health. Despite this, the mechanisms underlying socio-economic variations in adolescents’ diets remain unknown. There is therefore little evidence upon which to base nutrition promotion interventions for this target group. Potential explanations for the SEP variations in adolescents’ diets can be inferred from the existing literature on the determinants of dietary behaviour. For example, there is evidence that cognitive factors such as nutrition knowledge and health considerations, influence dietary intake [10] and that these influences are differentially distributed across SEP Ó The Author 2008. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: [email protected] doi:10.1093/her/cyn048 Socio-economic position and adolescent eating groups [11, 12]. Attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyle, eating and weight are also likely to influence dietary intake [13] and have been shown to vary across SEP. For example, low SEP adults tend to be less health conscious and have stronger beliefs in the influence of chance on health [14] and less positive attitudes towards healthy eating behaviour [13] compared with high SEP adults. Among female adolescents, those of low SEP have less awareness of the advantages of thinness, a higher threshold for concern about fatness and greater use of unhealthy weight control strategies [15]. There is also evidence that social and environmental factors influence dietary intake and that these influences vary across SEP. For example, social support for healthy eating, particularly from a partner or other family member, is a key influence on food choice [16], and individuals of low SEP have reported lower levels of support [17]. Home food availability, a correlate of fruit and vegetable intake in children and adolescents [18, 19], has also been shown to vary by SEP. Adolescents of low SEP report poorer home availability of fruit and vegetables [19, 20] and greater home availability of unhealthy foods (e.g. soft drink, potato chips and confectionery [20]) compared with their high SEP peers. Much of the research on dietary determinants has been based on the social cognitive theory (SCT) [10, 21], a theoretical framework that emphasizes the importance of factors within the cognitive, socioenvironmental and behavioural domains and their interactions. Few studies, however, have applied SCT constructs to examine adolescents’ diets [19, 22, 23, 24], and to our knowledge none has used SCT, or other theoretically derived models, to test mechanisms underlying SEP variations in adolescents’ diets. The aims of this study were 3-fold. Firstly, this study aimed to examine SEP variations among adolescents in three key indicators of dietary intake: fruit, energydense snack foods and fast foods. Secondly, this study sought to examine whether key cognitive and social/ environmental determinants of behaviour posited by SCT [i.e. self-efficacy; perceived importance of healthy eating; social observation (modelling) and healthy/unhealthy food availability in the home] are also patterned by SEP among adolescents. Finally, we aimed to determine whether socio-economic variations in these constructs explained socio-economic variations in adolescents’ diets. Methods Study design, procedure and participants As part of a study investigating changes in dietary habits during adolescence, adolescents and their parents/caregivers were administered self-completion questionnaires between September 2004 and July 2005. This study was approved by the Deakin University Ethics Committee, the Victorian Department of Education and Training and the Catholic Education Office. All co-educational state (government run) and Catholic secondary schools, located in the southern metropolitan region of Melbourne and the non-metropolitan region of Gippsland east of Melbourne, Australia, that included years 7–12 and had >200 enrolments, were invited to participate. Of the 70 schools (47 metropolitan and 23 non-metropolitan) that met these criteria, 37 schools (20 metropolitan and 17 non-metropolitan) agreed to participate. All students (n = 9842) from Year 7 (aged 12–13 years) to Year 9 (aged 14–15 years) were invited to participate. Teachers distributed parental consent forms to parents via students. In addition to requesting consent for their adolescent to participate in the study, parents were asked to report sociodemographic information including their gender, relationship to the child and highest level of schooling. They were also asked whether they would be willing to complete a questionnaire about their child’s eating habits. Parental consent was obtained for 4502 (46%) of eligible students, but due to absence from school on the day of testing, teachers administered surveys to 3264 adolescents (73% of eligible students with parental consent and 33% of all eligible students invited to participate). A parental survey was also mailed to 2534 parents who indicated that they would be willing to complete a questionnaire; of these, 1622 (64%) returned a completed survey. In the present study, the 497 K. Ball et al. maternal education measure was the only data used from the parental survey. Teachers administered an online food habits survey to students during class time when they had access to computers. The online survey was pretested with a small group of adolescents for clarity and functionality. Teachers instructed the students to type in the URL of the Youth Eating Patterns survey, which was provided to teachers along with additional information covering frequently asked questions and procedures to recommence the survey at a later time if students were unable to complete on the day. Almost all schools indicated that the major obstacle in obtaining parental consent would be due to the apathy of adolescents in returning forms. To facilitate this process, the researchers provided small gifts (movie and music vouchers) to be offered to all adolescents returning consent forms including forms denying consent. Further details of the sample and data collection procedures are described in a previous publication [25]. The present analyses are based on the subset of 2529 adolescents who had non-missing data for all the variables examined in this study. This subset did not differ from the full sample in terms of maternal education or the outcome variables, with the exception of fast food intake, where those excluded due to missing data had slightly higher average daily fast food consumption frequencies than the sample included in analyses (P < 0.05). Measures Outcome measures: food intake Consistent with other large-scale studies of dietary intake and eating behaviour of adolescents [19], food intake was assessed in the survey using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). This FFQ was based on the 2001 National Food and Nutrition Monitoring and Surveillance Project report [26], which described a number of validated indices useful in describing the food intake patterns of groups. Respondents indicated how frequently they had consumed 37 food items during the previous month. Seven response categories were ‘never or not in the last month’, ‘several times per month’, 498 ‘once a week’, ‘a few times a week’, ‘most days’, ‘once a day’ and ‘several times a day’. The present analyses are based on a subset of 10 food items from the FFQ, which were categorized into three food groups: fruit, energy-dense snacks and fast foods. These indicators were selected due to their importance in contributing to the healthfulness of overall diet. Fruit consumption is linked with decreased risk of a range of chronic diseases [27]. Frequent fast food consumption is associated with poorer dietary profiles, such as higher total energy, percent energy from fat and soft drink intake and lower consumption of fruit and vegetables, and also with excess weight gain, among adolescents [28, 29]. Studies have also shown that the consumption of energy-dense snack foods is associated with poorer nutrient profiles among children [30]. Initially, vegetable consumption was also examined, but the socio-economic variations in this outcome were minimal in this sample (P = 0.34). The frequency of consumption for each of the 10 food items comprising these outcomes in the past month was converted into a daily equivalent, which is an established method [31] that has been used in other dietary studies [32, 33]. Daily equivalent scores were calculated as follows: not in the last month (0.00 per day), several times per month (0.11 per day), once a week (0.14 per day), a few times a week (0.36 per day), most days (0.71 per day), once per day (1.00 per day) and several times per day (2.50 per day). The daily intake for each of the three food groups was calculated by summing the daily equivalence for food items in each food group. The estimated daily intake of the energydense snack group included the summed equivalence of four items (confectionary, cakes, sweet biscuits and potato crisps). The fast food group included the summed equivalence of five items [food from fast food chains, fish and chips, hot chips, pizza and pastry goods (savoury) like meat pies]. The daily intake of fruit included fruit as one item (fresh, canned, frozen or dried). Predictor measure Maternal education was used as the indicator of SEP for two reasons. Firstly, of the three commonly Socio-economic position and adolescent eating used indicators of SEP, education, income and occupation, it has been suggested that education is the strongest and most consistent in terms of predicting health behaviours [34]. Secondly, maternal education is an important determinant of dietary intake of children and adolescents and consequently is probably the most commonly used indicator of SEP in studies of childhood and adolescent eating behaviours [35–37]. Maternal education data were obtained from the parental consent form (if completed by the mother/female carer) or otherwise from the parent questionnaire (which assessed both parents’ education level). Response categories were categorized into three groups: ‘low’, having completed <12 years of secondary school; ‘medium’, having completed 12 years of secondary school and/or a technical or trade certificate/apprenticeship and ‘high’, having a University or tertiary (other formal, non-compulsory, education that follows secondary education) qualification. Mediators Cognitive, social and environmental constructs from SCT were included as mediators. Self-efficacy was assessed using items adapted from Project Eating Among Teens (EAT) [19]. Adolescents were asked three questions about their confidence in cutting down on ‘junk food’ (i.e. food that is low in nutritional value and typically high in energy): ‘If you wanted to, about how confident (sure) are you that you could cut down on junk food when you’re hanging out with friends’, ‘. at school’ and ‘. at home’ and three questions on confidence in eating more fruit in the same situations. Response options were given on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1: not at all confident through to 4: very confident. Responses were summed to provide two self-efficacy scores, one for cutting down on junk food (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80) and one for increasing fruit consumption (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84). Four questions, developed specifically for this study, assessed the perceived importance to the adolescent of health behaviours: eating healthy food, limiting junk food exercising and staying fit and limiting TV/DVD viewing. Responses were marked on a four-point Likert scale, from 1: not at all important through to 4: very important and summed (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74). The last two questions were included since previous studies demonstrate that dietary intake is closely linked to physical activity [38, 39] and TV/DVD viewing [40, 41]. Social observation of the eating behaviour of two key persons (best friend and mother) was assessed with items developed specifically for this study. For each, the adolescent provided a rating of their agreement (disagree, coded 1; not sure, coded 2 or agree, coded 3) with four separate statements: my best friend/mother eats healthy food, limits junk foods, eats vegetables most days and eats fruit most days. Two variables were calculated by summing responses to the four items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 for best friend and 0.71 for mother). In addition, two social support variables were derived by summing responses (1: never/rarely, 2: sometimes 3: often) to four items assessing support separately from friends and family: whether friends/ family make you feel good about what you eat, eat healthy food with you, discourage you from eating junk food and encourage you to eat healthy food (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76 for friend’s support and 0.72 for family support). These items were adapted from Sallis et al. [42]. The availability of different foods within the home environment (environmental predictor) was assessed with items adapted from Project EAT [19]. Respondents were asked how frequently (1: never/rarely, 2: sometimes, 3: usually, 4: always) the following items were available within the home: fruit, vegetables, cakes or sweet biscuits, potato crisps or salty snacks, chocolate or lollies and soft drink. The frequency of availability of fruit and vegetable items was summed (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73), as were the frequencies of the energy-dense snack items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80). Data analysis Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the sociodemographic and dietary characteristics of the sample, as well as the cognitive, social and environmental mediators. Since distributions on the 499 K. Ball et al. outcome variables energy-dense snack and fast food intakes were skewed, a square root transformation was applied to these variables to achieve more normal distributions. Differences by maternal education in the three dietary indicators and the mediating variables were examined using analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Where ANOVAs revealed significant differences, these were investigated further using post hoc tests with a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. The mediating effect of each cognitive, social and environmental variable was investigated using the Freedman– Schatzkin test of mediation [43]. The Freedman– Schatzkin test is based on the difference in the unstandardized regression coefficient for the association between an independent and dependent variable, unadjusted (s) and adjusted (s#) for the proposed mediator. The significance of the mediating effect is computed by dividing this difference in coefficients by its standard error and comparing the obtained value to a t-distribution with n 2 degrees of freedom. This approach represents a more powerful test of mediation effects than the commonly used Baron and Kenny [44] causal step approach, which has relatively low statistical power [45]. Such a powerful approach allows detection of mediating effects that may potentially be small due to the inclusion of confounding variables. A further advantage of this approach is its ability to test for mediating effects even when the main effects are not highly significant. Mackinnon et al. [46] provide a further discussion of cases in which the overall relationship of predictor to outcome is nonsignificant, yet mediation still exists. All regression models adjusted for sex, age (year level) and region of residence (metropolitan/non-metropolitan). Results The mean age of the sample on which these analyses are based was 13.5 years (SD = 1.3). More participants were female (54%) than male (46%), more resided in the metropolitan (66%) than in the nonmetropolitan (34%) region of Melbourne and more had mothers with a low (47%) than with a medium (29%) or high (24%) level of education. 500 Table I shows the distributions of dietary outcomes according to maternal education level. Compared with adolescents of higher SEP, those of lower SEP consumed fruits less frequently, but ate energy-dense snacks (borderline significant, P = 0.096) and fast foods more frequently. The distributions of social cognitive constructs by maternal education are also presented in Table I. With only two exceptions (social observation of best friend; social support for healthy eating from friends, both non-significantly associated with maternal education), all the constructs showed educational gradients in the expected directions. That is, compared with those whose mothers were highly educated, adolescents whose mothers had low education reported lower levels of self-efficacy for increasing fruit intake; lower levels of self-efficacy for reducing junk food; lower perceived importance of healthy eating; less healthy eating behaviours of their mothers; less familial support for healthy eating and less healthy and greater unhealthy food availability in the home. Maternal education explained 3% of the variation in fruit and fast food intakes and 0.2% in energydense snack intakes. Tables II–IV show the results of mediation analyses procedures applied to the prediction of fruit, energy-dense snacks and fast food intakes, respectively. Prediction of fruit intake by maternal education level declined significantly after adjusting for all predictor variables except for friend’s support, suggesting that socio-economic variations in fruit intake were mediated by these constructs (Table II). Based on the magnitude of t-values, cognitive factors, in particular the perceived importance of healthy behaviours, played the greatest mediating role (t(2527) = 11.9, P < 0.001). Table III shows the mediating effects of SCT constructs on the association between SEP and energy-dense snack food consumption. The strongest mediator of this association was the availability of energy-dense snack foods in the home (t(2527) = 17.8, P < 0.001). Friend’s support and the availability of fruit and vegetables in the home were the only two variables that did not mediate socioeconomic variations in energy-dense snack Socio-economic position and adolescent eating Table I. Means (SDs) or frequencies of demographics, dietary outcomes and social cognitive constructs by maternal education among adolescents (n = 2529) in Australia Maternal education Low (n = 1192) Sex (n, %) Male (1158, 46%) Female (1371, 54%) Dietary indicators (mean, SD) Fruit Energy-dense snack foods Fast foods Cognitive mediators (mean, SD) Self-efficacy increasing fruit (range 3–12) Self-efficacy reducing ‘junk’ (range 3–12) Perceived importance health behaviours (range 4–16) Social mediators Social observation (mean, SD; range 4–12) Best friend Mother Social support for healthy eating (mean, SD; range 4–12) Friends Family Environmental mediators (mean, SD) Fruit and vegetable availability in home (range 2–8) Energy-dense snack food availability in home (range 4–16) Mid (n = 737) High (n = 600) P-value* 545 (46) 647 (54) 323 (44) 414 (56) 290 (48) 310 (52) 0.83 (0.80)a 1.42 (1.43) 0.89 (1.14)a 0.90 (0.82)a 1.40 (1.37) 0.81 (1.09)a,b 1.19 (0.93)b 1.28 (1.28) 0.73 (1.04)b <0.001 0.096 0.010 9.13 (2.51)a 8.56 (2.39)a 11.42 (2.56)a 9.23 (2.39)a,b 8.65 (2.24)a 11.53 (2.46)a,b 9.50 (2.45)b 9.11 (2.23)b 11.85 (2.43)b 0.012 <0.001 0.002 9.10 (2.18) 10.89 (1.57)a 9.12 (2.17) 11.11 (1.38)b 9.27 (2.14) 11.37 (1.28)c 0.286 <0.001 6.77 (2.15) 9.52 (2.02)b 0.641 <0.001 7.60 (0.92)b 9.61 (2.52)b <0.001 <0.001 6.87 (2.23) 9.08 (2.10)a 7.40 (1.10)a 10.25 (2.52)a 6.85 (2.16) 9.28 (2.02)a,b 7.56 (0.93)b 10.20 (2.62)a 0.258 * Significance in chi-square test (sex) or univariate ANOVAs (dietary and social cognitive constructs). Different superscripts within a row indicate significant difference between means according to pairwise Bonferroni post hoc tests. SD, standard deviation. consumption. The inclusion of friend’s support in the regression model actually increased the magnitude of the association between SEP and energydense snack intake, suggesting a masking effect of friend’s support. That is, adolescents of higher SEP had slightly (though not statistically significantly) lower levels of friend’s support, and lower friend’s support predicted higher energy-dense snack intake. However, adolescents of higher SEP had lower energy-dense snack intakes, despite their lower levels of friends’ support. Friend’s support therefore masked some of the association of SEP with energy-dense snack intake. Finally, all variables except for friend’s support and social observation of best friend significantly mediated socio-economic variations in fast food intake (Table IV), with energy-dense snack food availability again the strongest mediator (t(2527) = 16.2, P < 0.001). Discussion This study confirmed previous reports that adolescents of low SEP generally have diets less consistent with current recommendations, based on a range of dietary indicators, than their peers of higher SEP [4–7]. The present study advances previous findings to demonstrate that most constructs of SCT also varied according to adolescents’ SEP. Compared with those whose mothers were highly educated, adolescents whose mothers had low levels of education scored relatively poorly on cognitive, social and environmental constructs posited by SCT to be supportive of healthy eating. The two exceptions were the constructs social observation of best friend and social support for healthy eating from friends, both of which were not significantly associated with maternal education in this sample. Possibly, adolescents may attend school and 501 K. Ball et al. Table II. Effects of adjustment for potential mediators in the association between maternal education and fruit intake among adolescents (n = 2529) in Australia Potential mediators s (mediator-unadjusted coefficient regressing fruit intake on maternal education) = 0.169 (SE = 0.021) Cognitive mediators Self-efficacy fruit Self-efficacy junk Importance of behaviours Social mediators Social observation Best friend Mother Social support Friends Family Environmental mediators Fruit and vegetable availability Energy-dense snack food availability s# SE s 0.148 0.149 0.149 0.019 0.020 0.020 0.165 0.151 s# SE t P-value 0.021 0.020 0.020 0.002 0.002 0.002 9.064 9.567 11.863 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.020 0.020 0.004 0.018 0.001 0.003 3.447 6.263 <0.001 <0.001 0.170 0.151 0.020 0.020 0.001 0.018 0.001 0.002 0.939 8.958 0.348 (ns) <0.001 0.151 0.157 0.020 0.020 0.018 0.012 0.002 0.002 8.944 5.606 <0.001 <0.001 s, unstandardized regression coefficient for association of fruit consumption with maternal education, adjusting for confounders (sex, year level and region of residence), before adjustment for mediator. In this model, predicting fruit consumption, s = 0.169, SE = 0.021; s#, unstandardized regression coefficient for association of fruit consumption with maternal education, adjusting for confounders and mediator; s s#, difference between the two regression coefficients, which, when divided by its standard error, can be compared against a t-distribution with n 2 degrees of freedom; SE, standard error; ns, not significant. socialize with friends from a range of socio-economic backgrounds, including those different to their own, so their friends’ eating behaviours and attitudes may also vary, which would explain the non-significant associations with adolescents’ own SEP. The present findings also demonstrate that variations in SCT constructs play an important role in mediating SEP variations in adolescents’ intakes of fruits, energy-dense snack foods and fast foods. This is a novel finding, since few previous studies have investigated socio-economic variations in such constructs, and to our knowledge this is the first study to explicitly test a theoretically based explanatory model of socio-economic variations in adolescents’ diets. There were several differences in the mediators that were most important for the three dietary outcomes examined. It is interesting that cognitive factors, particularly self-efficacy and the perceived importance of healthy behaviour, were important mediators of socio-economic variations in fruit consumption, while food availability 502 was a more important mediator for both consumption of energy-dense snacks and fast food. This finding is consistent with those of other studies that have also found that home availability may be a less important correlate of fruit intake than intakes of other foods in young people [47]. While we do not know the reasons for these differences, possibly, consumption of foods considered healthy may involve conscious decision making, while consumption of energy-dense snacks may be more impulse- and exposure-driven. However, there were also similarities in findings for the three dietary outcomes. For example, cognitive factors were found to be strong mediators across all three dietary indices. This suggests that, while increasing policy attention is paid to modifying structural environmental factors in an effort to improve dietary behaviours in socio-economically disadvantaged individuals [48–50], there remains a need for health promotion efforts to focus on cognitive factors such as self-efficacy and the value attached to health-promoting behaviours. Socio-economic position and adolescent eating Table III. Effects of adjustment for potential mediators in the association between maternal education and energy-dense snack intake among adolescents (n = 2529) in Australia Potential mediators s# s (mediator-unadjusted coefficient regressing energy-dense snack intake on maternal education) = 0.023 (SE = 0.012) Cognitive mediators Self-efficacy fruit Self-efficacy junk Importance of behaviours Social mediators Social observation Best friend Mother Social support Friends Family Environmental mediators Fruit and vegetable availability Energy-dense snack food availability SE s s# SE t P-value 0.016 0.007 0.014 0.012 0.011 0.012 0.007 0.016 0.009 0.001 0.001 0.001 9.961 11.150 11.324 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.022 0.020 0.012 0.012 0.001 0.003 0.000 0.002 2.902 1.901 <0.01 <0.05 0.024 0.020 0.012 0.012 0.001 0.003 0.000 0.001 4.669 2.939 <0.001a <0.01 0.022 0.003 0.012 0.011 0.001 0.026 0.001 0.001 0.978 17.832 0.328 (ns) <0.001 s, unstandardized regression coefficient for association of energy-dense snack consumption with maternal education, adjusting for confounders (sex, year level and region of residence), before adjustment for mediator. In this model, predicting energy-dense snack consumption, s = 0.023, SE = 0.012; s#, unstandardized regression coefficient for association of energy-dense snack consumption with maternal education, adjusting for confounders and mediator; s s#, difference between the two regression coefficients, which, when divided by its standard error, can be compared against a t-distribution with n 2 degrees of freedom; SE, standard error; ns, not significant. a Adjustment for support from friends was not a significant mediator, but rather increased the magnitude of the association between maternal education and energy-dense snack intake, suggesting that friend’s support had a masking effect on the association. Social factors appear to be less consistent mediators of socio-economic variation in dietary intakes among adolescents, and their importance seems to vary according to the dietary indicator under study and the source of support (familial versus friends). Overall, support for healthy eating from friends (and social observation of friends related to fast food intake) was less important than support and observation of family. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study [35], which also demonstrated that family circumstance was more strongly associated with adolescent’s dietary habits than were factors related to social groups at school. Social support from family may be more important because adolescents share more meals and eating occasions with family than with friends. Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. All data were collected by self-report and are subject to socially desirable response bias (which may have affected responses non-randomly across SEP groups) or other misreporting. Perceptions of the terms junk food or ‘healthy food’ may differ among adolescents or across sex, age or SEP groups. The response rate of 33% was low, and it is unknown how representative it is of the school population as we could not collect data from those not consenting. The low response could potentially bias our sample towards socio-economically advantaged groups since previous studies show that nonrespondents tend to be persons from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds [51]. In our sample, however, a higher proportion of participants had mothers with low levels of education (47%) than had mothers with medium (29%) or high (24%) levels of education. The study was crosssectional, and hence strong conclusions about causal mediating pathways are not possible. We cannot assume that our constructs for SCT (e.g. self-efficacy for eating more fruit) actually cause adolescents to change their behaviour (e.g. eat more 503 K. Ball et al. Table IV. Effects of adjustment for potential mediators in the association between maternal education and fruit intake fast food intake among adolescents (n = 2529) in Australia Potential mediators s (mediator-unadjusted coefficient regressing fast food intake on maternal education) = 0.042 (SE = 0.010) Cognitive mediators Self-efficacy fruit Self-efficacy junk Importance of behaviours Social mediators Social observation Best friend Mother Social support Friends Family Environmental mediators Fruit and vegetable availability Energy-dense snack food availability s# SE s s# SE t P-value <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.037 0.031 0.036 0.010 0.010 0.010 0.005 0.011 0.006 0.001 0.001 0.001 8.538 12.279 9.059 0.042 0.035 0.010 0.010 0.000 0.007 0.000 0.001 0.000 5.324 0.999 (ns) <0.001 0.042 0.039 0.010 0.010 0.000 0.003 0.000 0.001 0.000 3.527 0.999 (ns) <0.001 0.036 0.027 0.010 0.010 0.006 0.015 0.001 0.001 7.041 16.242 <0.001 <0.001 s, unstandardized regression coefficient for association of fast food consumption with maternal education, adjusting for confounders (sex, year level, region of residence), before adjustment for mediator. In this model, predicting fast food consumption, s = 0.042, SE = 0.010; s#, unstandardized regression coefficient for association of fast food consumption with maternal education, adjusting for confounders and mediator; s s#, Difference between the two regression coefficients, which, when divided by its standard error, can be compared against a t-distribution with n 2 degrees of freedom; SE, standard error; ns, not significant. fruit). A large body of research has established that behaviour affects perceptions in many ways, particularly when these behaviours are repeated or ongoing, like daily food intake [52]. For example, people who already eat lots of fruit are more confident about their ability to eat more fruit than people who only eat fruit occasionally. Despite this, it is plausible that maternal education would have been in most cases established temporally prior to the development of the adolescents’ food-related cognitions and the social and environmental factors reported here. Further limitations of this study include the use of only one indicator of SEP (maternal education), although this is not atypical for studies in this field. Nonetheless, findings may have differed were occupation, income or family SEP considered. The dietary measures were based on frequencies rather than amounts, but we still found SEP variations in the expected directions. This study only assessed SEP variations in three dietary outcome measures: fruit, energy-dense snacks and fast food. Different 504 mediators may have been important for other dietary outcomes, such as vegetable intakes. Further, these three indicators alone should not be taken to represent overall dietary quality. Strengths of the study include the large, regionally diverse sample; the application of a well-established theoretical framework and the use of powerful statistical mediation techniques, which allowed the testing of mediating pathways even where main effects were not highly statistically significant (i.e. for energydense snack consumption). Acknowledging these limitations, the present results are important since little is known about the mechanisms underlying SEP variations in diet. The findings suggest that public health programmes and policies aimed at promoting healthy eating among socio-economically disadvantaged adolescents might focus not only on promoting the importance of healthy behaviour and self-efficacy for healthy eating but also on decreasing the availability of unhealthy foods in the home. This may require targeting both adolescents and their parents, Socio-economic position and adolescent eating who not only support and model healthy eating behaviours but also most likely control the availability of foods within the home environment. Increasing awareness of health and access to healthy foods could be achieved by overcoming barriers that prevent or hinder acquisition of healthy foods in homes, in low SEP areas particularly, such as advocating for local markets or home delivery. It is also noteworthy that the SEP variations in intakes of fruits, energy-dense snacks and fast foods were relatively small and that intakes of these foods were also not ideal in terms of health recommendations among adolescents of high SEP (for instance, high SEP adolescents consumed fruit on average just over once per day). Nutrition initiatives targeting all adolescents remain warranted, but this is particularly the case among those experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage. Further research is required to confirm these results longitudinally and also to examine why these SCT constructs vary by SEP. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying socio-economic variations in adolescents’ diets and dietary determinants is essential for promoting healthy eating and reducing socio-economic variations in diets at this important life stage. Funding Australia Research Council (DP0452044); William Buckland Foundation; National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship (479513 to K.B.); VicHealth Senior Public Health Research Fellowship to D.C. Conflict of interest statement None declared. References 1. Spear B. Adolescent growth and development. J Am Diet Assoc 2002; 102: S23–9. 2. Magarey A, Daniels L, Smith A. Fruit and vegetable intakes of Australians aged 2-18 years: an evaluation of the 1995 National Nutrition Survey data. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25: 155–61. 3. Striegel-Moore RH, Thompson DR, Affenito SG et al. Fruit and vegetable intake: few adolescent girls meet national guidelines. Prev Med 2006; 42: 223–8. 4. Giskes K, Turrell G, Patterson C et al. Socio-economic differences in fruit and vegetable consumption among Australian adolescents and adults. Public Health Nutr 2002; 5: 663–9. 5. Wardle J, Jarvis MJ, Steggles N et al. Socioeconomic disparities in cancer-risk behaviors in adolescence: baseline results from the Health and Behaviour in Teenagers Study (HABITS). Prev Med 2003; 36: 721–30. 6. Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Resnick MD et al. Correlates of inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents. Prev Med 1996; 25: 497–505. 7. Milligan R, Burke V, Beilin L et al. Influence of gender and socio-economic status on dietary patterns and nutrient intakes in 18-year-old Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998; 22: 485–93. 8. Höglund D, Samuelson G, Mark A. Food habits in Swedish adolescents in relation to socioeconomic conditions. Eur J Clin Nutr 1998; 52: 784–9. 9. Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z et al. Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. J Am Med Assoc 2006; 295: 2037–45. 10. Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Baranowski J. Psychosocial correlates of dietary intake: advancing dietary intervention. Annu Rev Nutr 1999; 19: 17–40. 11. Parmenter K, Waller J, Wardle J. Demographic variation in nutrition knowledge in England. Health Educ Res 2000; 15: 163–74. 12. Hupkens CLH, Knibbe RA, Drop MJ. Social class differences in food consumption. The explanatory value of permissiveness and health and cost considerations. Eur J Public Health 2000; 10: 108–13. 13. Hearty AP, McCarthy SN, Kearney JM et al. Relationship between attitudes towards healthy eating and dietary behaviour, lifestyle and demographic factors in a representative sample of Irish adults. Appetite 2007; 48: 1–11. 14. Wardle J, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003; 57: 440–3. 15. Wardle J, Robb KA, Johnson F et al. Socioeconomic variation in attitudes to eating and weight in female adolescents. Health Psychol 2004; 23: 275–82. 16. Van Duyn M, Kristal A, Dodd K et al. Association of awareness, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, and stage of dietary change with fruit and vegetable consumption: a national survey. Am J Health Promot 2001; 16: 69–78. 17. Inglis V, Ball K, Crawford D. Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration. Appetite 2005; 45: 334–43. 18. Hearn M, Baranowski T, Baranowski J et al. Environmental influences on dietary behavior among children: availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables enable consumption. J Health Educ 1998; 29: 26–32. 19. Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C et al. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: findings from Project EAT. Prev Med 2003; 37: 198–208. 20. MacFarlane A, Crawford D, Ball K et al. Adolescent home food environments and socioeconomic position. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2007; 16: 748–56. 505 K. Ball et al. 21. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: ASocial Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall, 1986. 22. Lien N, Jacobs DR, Klepp K-I. Exploring predictors of eating behaviour among adolescents by gender and socioeconomic status. Public Health Nutr 2002; 5: 671–81. 23. Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc 2002; 102: S40–51. 24. Molaison E, Connell C, Stuff J et al. Influences on fruit and vegetable consumption by low-income black American adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav 2005; 37: 246–51. 25. Savige G, Ball K, Worsley A et al. Food intake patterns among Australian adolescents. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2007; 16: 738–47. 26. Marks G, Webb K, Rutishauser I et al. Monitoring Food Habits in the Australian Population Using Short Questions. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2001. 27. Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L et al. The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83: 100–8. 28. Taveras EM, Berkey CS, Rifas-Shiman SL et al. Association of consumption of fried food away from home with body mass index and diet quality in older children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2005; 116: e518–24. 29. French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D et al. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes 2001; 25: 1823–33. 30. Rangan AM, Randall D, Hector DJ et al. Consumption of ‘extra’ foods by Australian children: types, quantities and contribution to energy and nutrient intakes. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008; 62: 356–64. 31. Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998. 32. Mishra G, Ball K, Arbuckle J et al. Dietary patterns of Australian adults and their association with socioeconomic status: results from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56: 687–93. 33. Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ et al. Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72: 912–21. 34. Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E et al. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health 1992; 82: 816–20. 35. Johansen A, Rasmussen S, Madsen M. Health behaviour among adolescents in Denmark: influence of school class and individual risk factors. Scand J Public Health 2006; 34: 32–40. 36. Northstone K, Emmett P. Multivariate analysis of diet in children at four and seven years of age and associations with socio-demographic characteristics. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005; 59: 751–60. 506 37. Rogers I, Emmett P. The effect of maternal smoking status, educational level and age on food and nutrient intakes in preschool children: results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003; 57: 854–64. 38. Lytle L, Kelder S, Perry C et al. Covariance of adolescent health behaviors: the class of 1989 study. Health Educ Res 1995; 10: 133–46. 39. Pate RR, Heath GW, Dowda M et al. Associations between physical activity and other health behaviors in a representative sample of US adolescents. Am J Public Health 1996; 86: 1577–81. 40. Boynton-Jarrett R, Thomas TN, Peterson KE et al. Impact of television viewing patterns on fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 1321–6. 41. Salmon J, Campbell KJ, Crawford DA. Television viewing habits associated with obesity risk factors: a survey of Melbourne schoolchildren. Med J Aust 2006; 184: 64–7. 42. Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB et al. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med 1987; 16: 825–36. 43. Freedman L, Schatzkin A. Sample size for studying intermediate endpoints within intervention trials of observational studies. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 136: 1148–59. 44. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51: 1173–82. 45. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM et al. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 2002; 7: 83–104. 46. Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol 2007; 58: 593–614. 47. Bourdeaudhuij I, te Velde S, Brug J et al. Personal, social and environmental predictors of daily fruit and vegetable intake in 11-year-old children in nine European countries. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008; 62: 834–41. 48. Flournoy R, Treuhaft S. Healthy Food, Healthy Communities: Improving Access and Opportunities Through Food Retailing. Oakland, CA: PolicyLink and The California Endowment, 2005. 49. Department of Health. Report of Policy Action Team 13: Improving Shopping Access for People Living in Deprived Neighbourhoods. London: Department of Health, 1999. 50. Department of Health. The Food and Health Action Plan. Food and Health Problems: Analysis for Comment. London: Department of Health, 2003. 51. Turrell G. Income non-reporting: implications for health inequalities research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54: 207–14. 52. Weinstein ND. Misleading tests of health behavior theories. Ann Behav Med 2007; 33: 1–10. Received on January 29, 2008; accepted on September 5, 2008

![Welcome [atlante.unimondo.org]](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/008245948_1-fccb5b4f724131bed1f7332aadc65a33-150x150.png)