* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download as a PDF

Separation of powers under the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

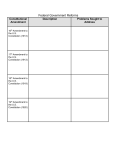

Constitutional amendment wikipedia , lookup

United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

United States Bill of Rights wikipedia , lookup

Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup