* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Dioscurica and the Roots of the Cyclic Tradition

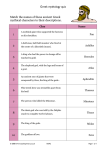

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction: The Prehistory of Greek Mythology and Poetics

The Indo-European Heritage

The “Cyclic” Tradition

I. Father Heaven, Heaven’s Daughter, and the Divine Twins

The rape of Nemesis

Shape-shifting, rape, and corov"

Heaven’s Incest

Helen and Saran‰y¨

ei[dolon and sávarn‰a

The birth of the Dvine Twins

II. Returning heroes

The Dioscuri as rescuers

Odysseus and the Phaeacians

Indo-Iranian rescue epyllia

The Vedic story of Bhujyu

III. Concluding remarks: the origins of the epic framework

1

Foreword

It would seem dubious to address the issue of roots and origins without reservations,

because one thereby awakens the notion of absolute beginnings, which is a matter of

metaphysics rather than of history or philology. By “roots” I simply mean conditions

not being explicit in the discrete texts, but nonetheless discernible in the comparative

record, aspects that lie beneath (but not necessarily at the bottom of) the texts

themselves. In the same spirit, beginnings and origins may, instead of being regarded

as something absolute, be understood as the current closure of historical vision. In the

case of myth, any attempt to trace its origin by merely focusing the plot is bound to

fail. However, one may endeavor to track down early versions of myths, as well as

early connotations of themes and agents, by paying attention to the tradition of their

performance. There are processes in history causing traditions to diverge, allowing

some parts to survive while others begin to break down and fade away. Although we

are seldom able to pinpoint exactly why, when, and where these processes occur, they

are always dependent on the maintenance, change, or lack of social interaction at a

given point in time. Only to some extent does this interaction serve the purpose of

communication in the present, so that a tradition may have to follow certain paths in

space. It may have to cross oceans, penetrate into deep caves, or meet obstacles in

deserts and jungles, yet the primary task of tradition is not to establish communication

in space, but to carry information through time. In general, tellers of myth are

particularly dependent on tradition since they address groups in the present with a

(real or pretended) message from the past, often explicitly urging these groups (or

representatives of these groups) to pass on the myth to future generations. An

effective method of safeguarding the transmission of such messages is to encode them

in poetic diction. In the widest and simplest sense of the concept, “poetic diction” may

imply a conventional modification (or even deformation) of everyday language,

which need not be restricted to merely aesthetic purposes. By exaggerating the

segmentation and intonation of spoken discourse, introducing rhymes, alliterations

and circumlocutions, a verbal message is created that is both easy to recognize and

easy to recall, but not necessarily easy to understand. Even though this laborious

encoding and decoding of poetic messages has to make sense to the parties involved,

the meaning of the message tends to be much more sensitive to change than the means

by which it is encoded. It is only when we have access to encoded messages

belonging to different yet once related traditions that we may hope to recover earlier

strata of meaning.

I have so far pretended to treat myth as an unambiguous concept. It is surely not.

One cannot be careful enough when it comes to separating this category from others. I

am only ready to make a few reservations at this point: myth is not defined by its

content. It may deal with virtually anything. Myth is rather defined by the means and

circumstances of its performance. The persistency in defining myth with reference to

content is due to the fact that such means and circumstances have become particularly

associated with certain sets of stories, but these stories do not become myths until

they obtain a certain social priority, until they are articulated, and when this happens

they become recognizable as marked speech (NOT Nagy). Furthermore, myths are not

always stories in the sense that they present a consistent course of events. On the

contrary, they are often highly allusive and insusceptible to narrative time (NOT).

The stories to be investigated in the following chapters are neither strikingly

similar on the surface, nor can they be restored to a single version in the discrete

cultures. They belonged to different societies and were told for a number of different

2

reasons. They have been altered and extended, abandoned and recovered. Only partly

have they entered into the mythical machinery, yet it is their mythical traits (the traits

of marked speech) that shall concern us here. These traits lie embedded in the names

and epithets of the agents, in the proximity of these names and agents, and in the

words and phrases with which these agents are associated. If these traits can be shown

to form parts of a larger whole, they will at once provide insights into a literary

heritage reaching far beyond the traditions compared.

3

Introduction: The prehistory of Greek mythology and poetics

The earliest literary monuments of the West, the Iliad and the Odyssey, owe at least

some of their magnificence to factors that preceded their composition. First of all one

must consider the reflexes of historical events, places, and persons in the tradition of

the Trojan War, particularly those belonging to Bronze Age Aegean, no matter how

little of this historical past that actually survived the force of epic imagination. Then

one must consider the importance of an already established tradition of the Trojan

War at the time of the composition of the Homeric poems, as reflected by early visual

art, by the poems of the Epic Cycle, and by the lyric of the Archaic Age. The

possibility of Near Eastern and other external literary influences on the Homeric

poems should also be taken into consideration. And last, but not least, one must

consider the aspects of a poetic and mythical heritage in early Greek literature that

were not restricted to the traditions of Greek tribes, but rather belonged to a much

older Indo-European tradition. In this chapter, I will pay particular attention to the last

issue, because it is the existence of an Indo-European heritage in Greek poetry that

has created the opportunity for the comparisons made in this study. An important task

in the following chapters will thus be to treat the mythical framework of the “Cyclic”

tradition in the same spirit as the linguistic, formulaic, and metrical traditions shared

by the peoples speaking Indo-European languages.

The Indo-European heritage

A suitable starting point is to look at the very notion of the poet and his craft, and in

this respect Pindar is a case in point. While referring to the epic past, Pindar may

employ specific images in order to situate himself in a long tradition of poetic

performance. Having described the killing of Memnon, for instance, he claims (Nem.

6, 53-54) that the older poets found a “highway” (oJdo;n ajmaxitovn) in such deeds,

and that he now makes this road his “own concern” (aujto;" melevtan) by following

along.1 This is a fitting image for the inner conflict of traditional composition, and it

applies particularly well to Pindar: that of being called to account for something new

and original while simultaneously relying on time-honored conventions. One would at

least expect this image to be an invention, but it could in fact belong to a traditional

imagery. This topic has been investigated by Marcello Durante, who gives numerous

examples of metaphors for poetic speech as a “path” in Vedic, Avestan, and Greek.2

Consider the following stanza in a Vedic hymn to the god Soma (9,91,5ab): “as of

old, you well endowed (one), prepare the paths (patháh‰ k√n‰uhi) for a new song

(návyase ... s¨ktý´ya)!” Not only does the emphasis on the “newness” of a hymn

appear as an isolated comparandum in Pindar (Isth. 5, 63: nevon ... u{mnon), but also

combined with the image of the “path of verses” in Ol. 9, 47-49: “awaken for them a

clear sounding path of verses (ejpevwn ... oi\mon); praise wine that is old, but the

blooms of hymns that are newer (newtevrwn).”3 If Durante was correct in regarding

this image as the residue of a shared poetic heritage, then Pindar’s way of expressing

his own relation to the epic past was in itself dependent on a traditional metaphor.

From an Indo-European perspective, this metaphor opens up a whole set of related

To judge from another passage in Pindar (Pyth. 4,246-248), ajmaxitov"

seems to denote a more lengthty exposition as opossed to the shorter

(but perhaps more challenging) oi\mo".

2

See Durante 1968 (= 1958): 242-260, see especially p. 245.

3

Tr. Race 1997: 153.

1

4

concepts. A still discernible trace of those who originally prepared this path, the

“track of the word”, incites the poet to become a “track-seeker”.4 Furthermore, the

poem itself may be compared to a vehicle (preferably a chariot) in which the poet

travels (cf. RV 2,31,1-4 and Ol. 1,110-111),5 and the very composition of poetry is

compared to the manufacturing of such a vehicle. It was in fact in this context that

James Darmesteter first recognized what he referred to as an Indo-European

“grammatical metaphor”, namely the description of poetry as a skill comparable to the

skill of a craftsman.6 A good example is RV 5,2,11: “for you (Agni) I have

manufactured (atak˜am) this praise poem (stómaÚ) as a chariot/wheel (ráthaÚ ná)”.

Darmesteter noticed that this figure could involve a number of synonyms for the

spoken word, one of which (vácas-7) was also attested in an Avestan compound

(vacastaπti-) serving as a technical term for “strophe”, but with the faded literal sense

“word-crafting”. Darmesteter could also show that the Greeks used the same figure in

their poetry. Once more in favor of deep-rooted metaphors, Pindar describes his

predecessors, the epic poets of the past, as the “craftsmen of verses” (ejpevwn

tevktone") (Pyth. 3, 112-114: Nevstora kai; Luvkion Sarphdovn ... ejx ejpevwn

keladennw`n, tevktone" oi|a sofoiv Ú a{rmosan, ginwvskomen “we know of Nestor

and the Lykian Sarpedon ... from such sounding verses as wise craftsmen joined

together8”). A similar example is found in Pausanias (10,5,8), who preserves a verse

concerning the mythical poet Olenus (the supposed founder of oracular hexameter

poetry): ... ejpevwn tektavnat∆ ajoidavn “he fashioned a song out of verses”. These

etymological matches as to both noun (Ved. vácas-, Av. vacah-, Gr. e[po") and verbal

root (Ved. •tak˜, Av. •taπ, Gr. •tekt) give us the hereditary formula *„ék∑os •*tetkñ

(•*tekñ∑).

Darmesteter’s find is of crucial importance for the study of Indo-European poetics,

because the formula simultaneously proves to be a part of the common poetic

repertoire and a poetic designation of the foundation of the whole repertoire. It is

significant that metaphors of this kind are less pronounced in epic poetry. One

explanation could lie in the generic differences. Pindar’s Epinikia and the Vedic

hymns seem to have more in common in that respect. They were intended as praise

poetry, celebrating the appearance and activity of particular individuals (men or gods)

at a given point in time. Since this poetry was more concerned with the situation of its

performance than the epic poems appear to have been, this gave the poet an

opportunity to be more present in his own creation. What we do find striking

examples of in Homeric poetry, on the other hand, is a set of phraseological and

stylistic characteristics that seems less restricted to a particular genre, but rather to

have constituted the archaic building stones of oral composition. Verbal and

conceptual parallels regarding the notion of lasting fame are particularly well-attested.

In the wake of Adalbert Kuhn’s famous Graeco-Aryan equation klevo" a[fqiton =

ák˜iti ¢rávah‰, ¢rávo ... ák˜itam (*kñlé„os ˆ‰dg∑hitom) “imperishable fame”, a

number of closely related formulas have been identified: fame (*kñlé„os) can be

4

Durante 1968 (= 1958): 244.

Durante 1968 (= 1958): 252f.

6

Darmesteter 1878 (= 1968): 116-118.

7

vácýÚsy ý¢ý´ ... tak˜am “with my lips have I crafted the words” (RV

6,32,1d).

8

Note that the verb aJrmovzw was closely associated with the chariot

(a{rma) among the Greeks from an early date onwards (cf. the

Myceanean word (h)armo- “wheel”).

5

5

associated with eternity and lifetime, it can be immortal, eternal, great, broad, etc.,9

but the concept also recurs in proper nouns such as the Mycenean woman’s name aqi-ti-ta (Ak∑hthitý), based as it seems to be on the compound name

*Ak∑hthitoklewejja,10 or the early Germanic man’s name HlewagastiR “having

famous guests” (cf. the Greek name Kleovxeno", which clearly matches the first

element of the Germanic name, and at least semantically corresponds to the second

element11). Attention has also been paid to the poetic characterization of horses and

chariots: the horses have golden manes, they are swift, prize-winning, and stronghoofed; the chariots are well-wheeled or well-running, they have golden seats and

golden reins.12

Parallels of a slightly different kind are found in Hesiod. These suggest that early

gnomic poetry became a vehicle of mythical motifs and religious attitudes reflecting a

different (but not necessarily younger) stratum of tradition than the one set off in the

Homeric poems. Quite remarkable is the triadic formula (Op. 514-16): diavhsi ... É

dia; ... e[rcetai É di∆ ... a[hsi ... (possibly a distorted variant of the climactic formula

*diavhsi ... É di∆ ... a[hsi ... É dia; ... e[rcetai), which seems to preserve the features of

an obsolete myth or a sexual metaphor also attested in Vedic and Hittite (similar

climactic formulas associated with the same collocation of concepts).13 Another

striking case is the encapsulation of the tabu “not to urinate standing up when facing

the sun” (Op. 727) in the Hesiodic formula ojrqo;" ojmeivcein, which is strongly

reminiscent of a Vedic phrase attested in a similar context: ¨rdhvó mek˜yými “I will

urinate standing up” (AV 7,10,2). This conspicuous parallel allows us to reconstruct

an Indo-European formula *„√Hdh„os •*h3meÁgñh as well as to retrieve the

rudiments of its ominous connotations.

We have so far been looking at some common properties of poetic language that

allow us to isolate an Indo-European poetic heritage in early Greek literature, but to

what extent are we able to isolate other aspects of tradition (such as the names and

attributes of gods) that would fit into this linguistic medium? To move from the

linguistic to the poetic plane already implies the preparedness to deal with a much

more fleeting and complex material, with regard to which the strict rules of grammar

and linguistic change no longer apply neatly. In the case of religion, however,

reconstructive endeavors appear more or less futile. It seems difficult enough to

describe the religions of documented societies, such as the Greek or Vedic, and in the

case of Indo-European religion any attempt in this direction necessarily depends on

the description of the documented societies. It is consequently not religion as a

complex whole (or the social, economic, political, ecological, etc. implications and

preconditions of this complex whole) that lends itself to such endeavors, but rather a

very limited number of concepts that were passed on by means of and as parts of

language. These concepts have been invested with different meanings in the

documented societies, and they are not necessarily better preserved in the oldest

societies. As we shall see below, there are some rare cases of continuity in the use of

divine names and some of the verbal tags with which these names were associated,

9

Schmitt 1967: 61-102. For a more recent treatment of the formula,

see Watkins 1995: 173-178.

10

Risch 1987: 3-11.

11

Watkins (1995: 246, 404) sees the zero grade *ghs- of European

*ghos-(ti-) in Greek xevno".

12

West 1988: 155.

13

Basic discussion in Watkins 1975, followed up by Jackson 2002,

Oettinger (forthcoming), and Watkins (forthcoming).

6

but it is important to keep in mind how limited a picture these traits give of an actual

“culture” (by which one does not only understand a heritage, but also the

incorporation of heritage). Nevertheless, this minor set of concepts may offer

interesting and relevant insights into, if not the culture of the proto-Indo-Europeans,

then at least the Indo-European traditions (or, to be more precise, the Indo-European

tradita) inherited by the documented cultures.

Historians of religions have readily applied theories of synchronic linguistics in

their attempts to describe and understand religious phenomena such as myth (e.g.

Lévi-Strauss) or ritual (e.g. Lawson/McCauley), because the rules that govern

language are believed to repeat themselves on other levels of social life. Ferdinand de

Saussure, one of the first to make this observation from a linguist’s point of view,

would also have insisted that language, just as any other social phenomenon, has a

synchronic and diachronic side to it, and that the study of language ideally involves

the appreciation of both sides. I would thus conclude that language, from the point of

view of religious studies, does much more than just mediate religious notions as they

appear in texts or in spoken discourse, or serve as a pattern for the description of

religion as a synchronic system. As a major vehicle of religious notions, language also

contains the ruins of its own past and to a limited extent also the ruins of such notions.

A well-known instance of Indo-European heritage in Greek religion is the name

“Zeus”.14 The Greeks, accustomed as they were to regard this god as the pater

familias of the divine household, addressed him as pavthr (most frequently in the

vocative Zeu` pavter ... “O father Zeus!”). The same usage is attested in Vedic, where

one finds an etymologically matching name Dyáus, occasionally also in the vocative

Dyàus (pronounced as a disyllable díaus) and followed by the corresponding epithet

pítar “father” (cf. AV 6,4,3c). The frequent vocative usage was generalized in some

languages, which explains Latin Iuppiter, Umbrian Iupater, and “Illyrian”

Deipavturo" as derivations from the vocative *dÁé„ ph2tér, not from the expected

nominative *dÁé„s ph2tÿ´r. Watkins argues for reflexes of a similar epithet in Old

Irish and Hittite, where he considers the Indo-European semantics to be better

preserved.15

A hereditary extension of the epithet “father” is also seen in the Vedic, Avestan,

and Greek (perhaps also Latin) characterizations of this (or some other) god as “father

and begetter” (*ph2tÿ´r gñnh1tþr).16 Cf., for instance, RV4,1,10d: dyáu˜ pitý´ janitý´,

RV 1,164,33a: dyáur me pitý´ janitý´, Y 44,3b: za…ƒý patý, Aeschylus, Hiket. 206: ...

Zeu;" de; gennhvtwr, Euripides, Ion 136: Foi`bov" moi genevtwr pathvr, Ennius,

Annales 120: o pater, o genitor17. The comparison between RV 1,164,33a and Ion 136

deserves particular attention, because (as noticed by Schmitt18) the phrases also share

the enclitic personal pronoun me/moi. Although Schmitt seems to regard the match as

haphazard, I would not rule out that the phrases contain traces of the same cultic

formula. The liturgical context of the current passage in Ion is quite explicit (Ion

praying in the temple of Apollo with a laurel broom in his hand), and as for the RV

this context must be taken for granted in any case. We would thus be dealing with an

14

For a useful etymological survey, see Schindler 1978: 999-1001.

Watkins 1995: 8.

16

Schmitt 1967: §290ff.

17

Ennius may simply have adopted a Greek formula, which neverthess

gives a more archaic impression in terms of word order (in accord

with Behagel’s law) than the attested Greek formulas.

18

Schmitt 1967: §291.

15

7

example of a formula vaguely reflecting the Indo-European language of prayer:

*(dÁé„s) moÁ ph2tÿ´r gñnh1tþr “DÁe„s/GOD is my father and begetter”.

The basic meaning of the verbal root from which the noun *dÁé„- was derived

seems to have been “to shine” (as seen in the extended Vedic root •dyut), and this

sense also survives in derivative nouns meaning “heaven” (cf. the meaning of Vedic

dyáus in certain contexts) or “day” (cf. Latin diÿs, Armenian tiw, or the Greek

compounds e[ndio" “at midday” and eujdiva “fair weather”). This does not imply that

the Greeks placed Zeus on an equality with the diurnal sky, nor that the aspects

inherent in his name inevitably sheds light upon his subsequent role in Greek

mythology. There are, however, some characteristic features that could be approached

in this manner. In his capacity as the god who decides the human fate, Zeus is

idiomatically said to “bring on the day” (ejp∆ h\mar a[gein/ejf∆ hJmevrhn a[gein). An

early example is Od. 18,136f.: toi`o" ga;r novo" ejsti;n ejpicqonivwn ajnqrwvpwn Ú

oi|on ejp∆ h\mar a[gh/si path;r ajndrw`n te qew`n te. Another example is found in

Archilochus (West, fr. 131), according to whom the mood of mortals vary “as the day

that Zeus brings on” (oJpoivhn Zeu;" ejf∆ hJmevrhn a[gh/)”.19 Considering the early

date of Archilochus’ poetry20, it does not seem necessary to interpret fr. 131 as an

allusion to Homer, and we may consequently regard the two examples as independent

manifestations of the same traditional locution.21 It would thus seem all the more

relevant to compare, as Martin West has done,22 Zeus as the god who “brings on day”

with Uranos as the god who “brings on night” (cf. Theog. 176: h\lqe de; nuvkt∆

ejpavgwn mevga" Oujranov" ... “and great Uranos came, bringing on night”). These

and other examples suggest that the two formulas (or locutions) belonged to a preHomeric tradition, and that they shared the same thematic background:

A. *ejp∆ h\mar a[gwn Zeuv"

B. nuvkt∆ ejpavgwn ... Oujranov" (Theog. 176)

It is plausible that Zeus and Uranos were occasionally conceived as complementary

deities, perhaps even as a pair. Although the Greek material is not comprehensive

enough to confirm this hypothesis, a stronger case can be made by bringing in IndoIranian comparanda.

I have elsewhere reconsidered the possibility that the Vedic gods Mitra and

Varun‰a (often addressed as a pair) retain features that associate them with the

diurnal and nocturnal aspects of the sky. 23 According to the Taittir^ya SaÚhitý (TS

19

This notion is echoed in Pindar’s famous dictum regarding the

“creatures of the day” (ejpavmeroi) (Pyth. 8,95-8,96). Cf. also the

English word “ephemeral”.

20

The memorial of Glaucus, son of Leptines (SEG 14.565), which has

been dated to the late 7th century, clearly belonged to the Glaucus

addressed in Archilochus’ poetry.

21

Fowler’s (1987: 26f.) discussion of the paralell halts a little,

because he seems to presuppose that either Homer or Archilochus has

to be derivative.

22

West 1966: 218.

23

Jackson 2002b. The hypothesis that Mitra and Varun‰a represent the

reflexes of a much older divine pair, which was subjected to decoding

and superposition among the Indo-Iranians, remained a hallmark in

Dumézil’s theory of bipartite sovereignity. The shared features of

Zeus/Uranos and Mitra/Varun‰a (not least their association with day

and night) played an important role in Dumézil’s early writings (cf.

8

6,4,8), Varun‰a produced the night as opposed to Mitra who produced the day

(mitrau ’har ajana yad varun‰o rýtriÚ).24 Another noteworthy example is the

description of the two gods as mutually pressing together (in the night) and opening

out the rush-work (in the morning) (AV 9,3,1825):

ítùasya te ví c√tý´myápinahyam aporn‰uván

várun‰ena sámubjitýÚ mitráh‰ prýtárvyubjiatu

“of thy rush-work I unfasten what was tied on, uncovering: [thee] pressed together by

Varun‰a, let Mitra in the morning open out” (Whitney (tr.))

Furthermore, the nocturnal aspects of Varun‰a are clearly hinted at in descriptions of

his secret supervision of human action. He wears the night sky as a golden garment, to

which his “spies” (spá¢as) have been attached (RV 1,25,13).26 Zeus is associated with

a similar notion at Op. 252-53, but it is also likely to have been an early (if not to say

earlier) property of Uranos as well since he was more intimately associated with the

starry sky (cf. his epic epithet ajsterovei"). A pre-Socratic fragment (Critias, Sisyphus

33) refers to the “star-eyed frame of the sky” (ajsterwpo;n oujranou` devma") and

there is a depiction of Uranos on the southern frieze of the Pergamon Altar with a pair

of eyes (possibly owl’s eyes) on his wings.27

Despite such typological points of agreement, the etymological connection

between várun‰a and oujranov" has been considered untenable for nearly a century.

Jacob Wackernagel’s objection (against Kretschmer and Solmsen) in Sprachliche

Untersuchungen zu Homer28 was soon canonized as yet another successful attempt to

shatter the illusions of 19th century comparative mythology. The etymology was first

seriously reconsidered by George Dunkel in 1987, who in his Zürich inaugural lecture

showed that the comparison may in fact be perfectly sound (Dunkel 1988-1990). He

interpreted várun‰a as a synchronic continuator of the Vedic stem varu- (< PIE

*„oru-) “to encompass, cover”, surviving with different syllabification (*„or„-) in

oujranov". As regards similar formations, the nouns var¨t√ñ, vár¨thý, and the adjective

var¨thía are notable. The etymology implies qualitative vowel gradation*„eruno/*„oruno- (cf. Ved ápas/ý´pas), Greek *ejranov"/Aeolic ojranov" (cf. Greek

ejcurov"/ojcurov") (< *„er„n‰o-, *„or„n‰o-). This view is compatible with the

view of M. Kümmel, who reconstructs a PIE root *„er- “aufhalten, (ab)wehren”,

preserved in Greek and subjected to merger with *„el- “einschließen, verhüllen” and

*H„er- “stecken” in Indo-Iranian.29 The two names would thus be formed on the

same verbal root meaning “to cover” and a suffix –no- (as in Latin dominus) denoting

worldly or heavenly dominion. Dunkel’s interpretation is certainly not definitive, but

Dumézil 1948), but he seems to have lost his interest in the issue

after 1948.

24

Other examples, most of which are listed in Dumézil 1948: 90ff.,

are: TS 2,1,7; 5,6,21; TB 1,7,10,1; AV 9,3,18; 13,3,13; AVP 2,72,2 (=

2,80,2).

25

A similar notion occurs in AV 13,3,13: “This Agni becomes Varun‰a

in the evening; in the morning, rising, he becomes Mitra” (Whitney

(tr.)).

26

Cf. also the description of Ahura Mazd˝ (theological counterpart

of Varun‰a and possible avatar of Indo-Iranian *„aruna) in Yt. 13.2-3

(Jackson 2002: 50ff.).

27

Discussion in Simon 1975: 35.

28

Wackernagel 1916: 136 A. 1.

29

LIV 625f.

9

there are some further matches to back it up. He notices himself that the same

adjective (*„érH-) is used to describe the gods as “wide” (*„érH-) or “wide-looking”

(cf. RV 1,25,5bc: várun‰aÚ ... urucák˜asam ~ Op. 45 (and passim): oujranov"

eujruv"). Another conspicuous parallel is that both gods are said to be (or have) a

“firm seat (*sédos)” (RV 8,41,9d: dhruváÚ sádah‰ ~ Theog. 128: ajsfale;" e{do").

It is noteworthy that Vedic Dyaus/dyaús and Greek Uranos/oujranov" appear to

have undergone the same theological and semantic development (e.g. the relative

passivity of the gods and the occasional changeover of the proper nouns to nouns

meaning “sky”), especially when one considers the extent to which this weakness is

“restored” by their Greek and Vedic namesakes. There is consequently no need to be

overly pessimistic when it comes to outlining the prehistory of the two gods, because

some of the features that have been lost or fossilized on the one side of the

comparison may still be vital on the other. As we shall see in the chapter to follow,

there is also textual evidence for a less passive, but often overlooked aspect of Dyaus

that would support his conformity with Zeus. In the light of these new data, I would

cautiously argue that Dumézil’s old idea concerning Zeus/Uranos as the Greek

manifestations of the “two sovereigns” (by the side of such pairs as Mitra/Varun‰a

and Germanic *T^waz/Wþµanaz) deserves reconsideration. If the observation is

correct, the Greek comparandum would contain onomastic features that were only

retained in corrupted form elsewhere: the name of the (diurnal) sky-god as a part of

the Germanic pair (*T^waz (*dei„ós “heavenly, god” •*dÁé„) and the name of the

nocturnal “coverer” as a part of the Vedic pair: *dÁé„s (or *dei„ós) and *„eruno.

Scholars discussing the Indo-European stratum in Greek myth and epic, and if so

only in passing, have been in habit of referring to the common origin of Eos and

Vedic U˜as (*h2e„sþ´s) (cf. also the Roman and Baltic continuators) as a particularly

strong case. From the point of view of classical literature, the etymological match has

been backed up with important observances as to phraseology and theme30, and

Boedeker convincingly argues that Aphrodite absorbed many characteristic features

of the Indo-European Dawn-goddess that would no longer apply to Eos. As is

generally assumed, Indo-European *h2e„sþ´s bore the epithet *di„ós dhugh2tér

“daughter of DÁe„s”, although this epithet need not have been her’s exclusively. She

had a characteristic smile (•*smeÁ), which she seems to have shared with her father

(cf. RV2,4,6d)31, and the Vedic characterization of her “desire” (vánas- (< *„énos))

(cf. RV 10l,172,1: ý´ yý´hi vánasý sahá “come here (U˜as) with your desire”) may

provide a clue to the origin of the Latin name Venus.32 Just as in the case of Zeus and

Dyaus, there are still some crucial points of thematic (and possibly phrasal)

interference that have been overlooked. This may also be true of the much-debated

Divine Twins, the Greek Dioscuri, whose Vedic counterparts appear as allies of the

Dawn-goddess. I shall return to these issues in the chapters to follow, however, and

see no reason to delve into details here.

Since I have left out data that seem less relevant to the main topics of this study,

this discussion has by no means been exhaustive as regards the formulaic and

onomastic parallels in early Indo-European (especially Greek and Vedic) texts.

Nevertheless, some further cases of scholarly progress should be mentioned.

Etymological equations that were for a long time considered fallacious and overly

speculative, especially since they called to mind Friedrich Max Müller’s and Adalbert

30

See, for instance, Boedeker (1974), Clader (1976), and Nagy (1990

(= 1978)).

31

See discussion in Boedeker (1974: 24ff) and Dunkel (1990: 9).

32

Dunkel 1990: 10.

10

Kuhn’s 19th century Naturmythologie, have been reconsidered by a new generation of

linguists. It should be emphasized that these scholars use different and refined

methods of comparison, and that the problems are approached from a new (yet far

from programmatic) angle. Besides Dunkel’s reconsideration of Uranos and

Varun‰a, I would like to add Johanna Narten’s thoughtful notes on the etymology of

the name of Prometheus (Doric Promaqeuv"), who is compared to Vedic Mýtari¢van

“robbing” (mathný´ti, •math (sometimes with the preverb pra-)) the heavenly fire.33

This new interpretation makes a strong case the existence of an obsolete Greek

compound name (derived from Indo-European *promýth2e„-) that was no longer

semantically perceptible to the epic poets (they instead associated this name with the

verb manqavnw). Worth attention is also Michael Estell’s reconsideration of the

common background of Orpheus and àbhu (first suggested by Christian Lassen in

1840).34 The names may indeed reflect the same noun (*h3√bhé„-)35, but Estell also

shows that the two figures share similar verbal tags as regards their occupation (both

are “craftsmen ” associated with the verbal root •*tetkñ) and parentage (both fathers

are “cudgel-bearers” associated with the noun *„agñro-).

As I hope to have shown in this short survey, the oral traditions providing the basis

of poetic composition in the Archaic Age were themselves cast in a mould that

preceded much of what we associate with the “Greeks” comprising these traditions.

Some discrete comparisons may appear speculative or supported by haphazard

agreements, but if the body of evidence is judged as whole, there can be no doubt that

certain aspects of Greek poetry (prosody, formulaics, divine epithets, etc.) formed a

part of the same Indo-European continuum as the Greek dialects. The crucial issue is

rather where this continuum ends and to what extent it may still shed light upon the

development of local phenomena? Before we touch upon these issues, however, it

seems advisable to invert the perspective and start by looking at the development of

early Greek poetry as forming a part of a Hellenic continuum.

The “Cyclic” tradition

The debate on the authorship, design, and transmission of the Homeric poems and the

poems of the Epic Cycle has been going on for at least two and a half millennia,

making it one of the most tenacious scholarly issues in the West. It was a major

concern of the Hellenistic philologists, but even the rhapsodes, who were the first to

perform these texts, may have anticipated the editorial debate.36 Since my own project

does not directly relate to the final acquisition of epic poetry, but rather to that which

preceded it, this section is only meant to serve as a background based on some recent

achievements. In his new book The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer & the Epic

Cycle, Jonathan S. Burgess gives a thorough and updated survey of the early history

of epic poetry in Greece, and I shall to a great extent follow his lead in trying to give a

short summary of this topic.

References to the “Epic Cycle” in Greek literature usually bear upon a particular

collection of epic poems, beginning with the union of Gaia and Uranus, and closing

with the return and death of Odysseus. Although titles of such poems have survived

33

Narten 1960. Cf. Kuhn 1886: 18.

Estell 1999.

35

As I have pointed out elsewhere (Jackson 2002a: 84), there may be

more to the meaning of this name than Estell himself makes out of it.

36

Burgess 2001: 13.

34

11

(Titanomachy, Oedipodia, Thebais, Epigoni, and those specifically concerning the

Trojan War (the so called “Trojan Cycle”): Cypria, Aethiopis, Little Iliad, Iliou

Persis, Nosti, Telegony), the poems themselves can only be discerned through a small

number of fragments and prose summaries. By the side of the Homeric poems, which

at least in some sense were considered to belong to the Cycle (the Iliad following the

Cypria, and the Odyssey following the Nosti), these (and possibly other, no longer

familiar) epic poems constituted an indispensable narrative resource, from which the

Archaic lyrical poets and the Attic tragedians collected the majority of their material.

The Epic Cycle was most likely manufactured in order to create a coherent

collection of epic poetry during a period subsequent to the creation of the individual

poems. Although the notion of a “cycle” of epic poetry may itself be very old37, the

collection referred to as the “Epic Cycle” was evidently familiar to the authors of the

Hellenistic period, but need not be much older than that.38 Nevertheless, some of the

poems used in the manufacturing of the Epic Cycle may at least belong to the Archaic

Age, and the oral tradition on which these poems were based was in its turn much

older. Burgess labels this tradition the “Cyclic” tradition, and his definition of this

term will remain implicit throughout this study. By “Cyclic” tradition he means “the

living pre-Homeric tradition of the Trojan War that led to the Trojan War poems in

the Epic Cycle and continued with the Cycle as a major manifestation of it. This

tradition preceded the Homeric poems but then in turn was gradually overshadowed

by them.”39

Despite the enormous influence of Homeric poetry on literature and visual art in

the Classical and Hellenistic periods, it is evident that the tradition of the Trojan War

was still an independent oral tradition in the Archaic Age. Whenever motifs outside

the Homeric corpus appear to represent the same or similar scenes as those found in

the Iliad or the Odyssey, one should consequently not take for granted that some of

the Homeric poems had served as the main source of artistic inspiration. As a matter

of fact, the majority of Trojan War images represented by artwork from the 8th and 7th

century are not even found in (or are at least not in direct accord with) the Homeric

poems, but should rather be defined as “Cyclic”.40 As regards early poetry, modern

scholarship is still open to the idea that phrases and similes attested in Homer can

only recur in other (and younger) poetic texts as Homeric allusions. This idea is most

likely wrong, and probably emerged as an effect of the gradual canonization of the

Homeric poems in latter periods. In most cases, discoveries of “intertextuality” in

early poetry would rather point to the existence of a shared oral tradition (including

formulas, phrases, and collocations of words) than to a submission to the supremacy

of Homeric poetry.41 It is also far from certain that the material found in the Epic

Cycle reflects a post-Homeric ambition to fill in the gaps left by the Homeric poems.

37

We have already seen that the metaphorical description of the

craft of poetry as the joining together of a wheel or a chariot may

belong to an Indo-European poetic heritage. This point is stressed by

Gregory Nagy (1996: 89-91), who also links this metaphor to the name

of Homer himself (“he who joins together” homo- + ar-), arguing that

(p. 90) “if this etymology is correct, then the making of the Cycle,

the sum total of epic, by the master Homer is a metaphor that

pictures the crafting of the ultimate chariot-wheel by the ultimate

carpeenter or ‘joiner.’”

38

Burgess 2001: 7ff.

39

Burgess 2001: 33.

40

Burgess 2001: 53-114.

41

Burgess 2001: 114-131

12

This ambition may have characterized the compilation of the material in the

Hellenistic period, but the individual poems are more likely to have sprung from the

same “Cyclic” tradition as the Homeric poems. Since this was a fluid oral tradition,

and since the poems were probably composed and transmitted orally before they were

written down, it is hard (if not even misleading) to imagine a fixed date of origin. But

even if the poems of the Epic Cycle were composed in post-Homeric times (as most

scholars assume), it does not necessarily follow that they were dependent on or

inspired by the Homeric poems. This being so, some problems associated with the socalled “Homeric Question” essentially concern the development of the “Cyclic”

tradition as a whole, not so much the creation of the Homeric poems as such. That this

tradition reaches far back in prehistory is generally accepted, but is it possible to be

more specific when it comes to characterizing its constituents and approximating its

age?

A focal point of Greek epic, the city of Troy or Ilios (*Ûivlio") has since the days

of Heinrich Schliemann been identified with the ruins on the hill of Hisarlõk on the

eastern shores of the Dardanelles. With the discovery of Hittite and the other

Anatolian languages, furthermore, the period and area to which the Trojan legends

seem to refer slowly emerged from the darkness of prehistory. It is now generally

assumed that the name and location of the city of Ilios coincides with that of the place

referred to by the Hittites in the 2nd millenium BC as Wilusa. The “Cyclic” tradition is

thus not the only historical fact that has to be acknowledged here, but also parts of the

narrative it transmits.

Around 1290 BC, the kingdom and city of Wilusa was drawn into conflicts

involving the prince Pijamaradu from the lands of Arzawa, the kings of the lands of

Aúúijawa, and the great Hittite kingdom. Form the early 14th century BC onwards,

Mycenean culture had constituted an important element of power along the coast of

Asia Minor, not least through its early presence in Milawanda (Miletus). There is little

doubt today that the people of Aúúijawa, as referred to in Hittite sources from the

archives of Óattuπa (the capitol of the great Hittite kingdom), should be identified

with the Mycenean Greeks and the name Aúúijawa (or Aúúia) seen as an early reflex of

the ethnonym ∆Acaioiv. In the second half of the 14th century BC, the Hittite armies

of Mursili II attacked Arzawa, which was at that time the most powerful state in

western Asia Minor. This caused the king of Arzawa, Uúúaziti, to flee from his capitol

Abasa (Ephesus), seeking the protection of the kings of Aúúiwava on the Greek

mainland. Although Uúúaziti died soon after his exile, his family remained in

the lands of Aúúiwava. The eagerness of this royal family to regain power in its native

country was most likely an underlying reason for the prince Pijmaradu (probably the

uncle of Uúúaziti) to begin political and military campaigns along the coastal districts

of Asia Minor. In doing so he was supported by the kings of Aúúiawa, who allowed

him to use Milawanda as a base of his campaigns. As an effect of these activities,

Pijamaradu also posed a direct threat to the kingdom of Wilusa, which was provided

with military support from the neighbouring state Sÿúa through instruction of the

Hittite king. Since the Hittites were concerned about the political stability in western

Asia Minor, and since king Alaksandus of Wilusa wanted to secure his position on the

throne, Alaksandus concluded a treaty with the Hittite king Muwatilli II (1290-1272),

which turned Wilusa into a Hittite vassal state. In a letter (the so called Tawaglawaletter) from the Hittite king Óattusili II (ca 1265-1240), the king of Aúúiawa is urged

to bring pressure to bear on Pijamaradu, with whom Óattusili wants to arrange a

13

meeting. It remains unclear if these efforts paid off or not, nor do we know if

Alaksandus still ruled in Wilusa at that time.42

The picture of the complex political history of western Asia Minor in the 2nd half

of the 2nd millenium BC is obviously rather blurred, and it almost invariably derives

from Hittite sources. Nevertheless is it tempting to see in some of the names of cities,

countries, peoples, and persons a pattern that is echoed in the Greek legends of the

Trojan War. It would of course be completely misleading to approach the Trojan

tradition as the representation of historical facts, but some of the events referred to in t

he Hittite sources may very well have triggered the shaping of the epic traditions

passed on by the Greeks. The very few hard facts of history that can be distinguished

in this elastic epic tradition seem to reappear in a heavily distorted form. The only

attested kings of Wilusa are Alaksandus and his predecessor Kukkunni, but in Greek

epic the name Kukkunni only (but not certainly) comes out as the name of a Trojan

ally (Kyknos). The name Alaksandus undoubtedly matches Greek Alexandros, the

other name of the Trojan prince Paris, but the name Priamos can at best be interpreted

as a reflex of the Luvian name Pari-muwas (without any documented associations

with Wilusa). It is significant that Alaksandus, in the treaty mentioned above, calls the

gods of the city as his witnesses, among which the only god mentioned, Appaliunas

(the possible restoration of ]a-ap-pa-li-u-na-aπ as preceded by a lost ideogram

DINGIR denoting “god”), is closely reminiscent of Apollo (*apelÁþn), the patron of

Troy in Greek epic.43 The fact that Alaksandus bore a Greek name suggests that he

had near relations to the people of Aúúijawa, but this people nevertheless posed an

indirect threat to his kingdom by supporting Pijamaradu. It seems reasonable to

assume that Anatolian languages were spoken in Wilusa at the time of Alaksandus

(especially Luvian44), and the description of Trojan institutions in Greek epic (such as

levirate marriage) occasionally correspond to Anatolina institutions. 45 There are,

however, neither archaeological nor historical indications of a sack of Wilusa during

the Mycenean period.

As one might expect, the discrepancy between documented history and epic

memory is quite profound, yet nothing excludes that songs of (W)ilios were already

beginning to appear in the Mycenean period46, or that these songs were to become a

mainstay in the development of the “Cyclic” tradition. The preferable medium of such

creations would have been the hexameter and other hereditary techniques of oral

composition, because there is nothing to suggest that written records were used by the

Greeks for such purposes before the 8th century BC. Even long after the development

of alphabetic writing, the composition and performance of epic poetry remained a

predominantly oral concern. Some metrical irregularities in early epic poetry can in

fact be restored if the formulas are transformed into the language of the Pylos tablets

42

For a comprehensive treatment of these issues, see Starke 1997.

Cf. dicussion in Watkins 1994 (= 1986) and 1995: 149.

44

As Frank Starke points out, this is even suggested by the

representation of the name “Wilusa” in Hittite sources.

45

Watkins 1994 (= 1986): 705f.

46

It is even possible that the Luvians had an epic lay about the

city of Wilusa (a “Wilusiad”), although nothing can be said of its

content. This was first suggested by Calvert Watkins (1994 (= 1986):

713ff.), who found a Luvian analogue to Ûivlio" aijpeinhv (“steep Ilios”),

the traditional Homeric epithet for Troy, in the isolated Luvian

verse (KBo 4.11,46) aúú=ata=ta alati awienta Wiluπati (“When they

came from steep Wilusa”). The same epithet probably recurs in the

fragmentary paragraph (KUB 35.102 (+) 103 iii 11) ýlati=tta aúúa LU´iπ awita [ (“When the the man came from steep [...”).

43

14

or an even earlier stage of linguistic development, for which there is only comparative

evidence. This and other circumstances (such as freedom in the placing of preverbs)

have led many to believe that the tradition of epic song as we know it at least reaches

back to the early Mycenean period (ca 1700 BC).47

Since there is both external and internal evidence for the use of metrical patterns

and a poetic vocabulary that precede the historical period to which the epic poems

seem to refer, it is reasonable to assume that this pre-historical period consisted of

more than empty techniques and obsolete vocabulary. Many of the narratives were

probably just as traditional as the narrative techniques. As suggested by the treatment

of indigenous myths in Rome48, it is possible that the Greeks located traditional (or

mythical) stories in a historical or pseudo-historical environment. In the Archaic and

Classical periods, however, the Mycenean past was already distant enough to form

association with a mythical past, and many of the persons and places associated with

this age had already become the foci of religious attention. Consequently, the stories

located in this environment should not first of all be held to relate a partly forgotten

historical past, nor should we assume that they originally developed in this

environment. As I will try to show in the chapters to follow, important aspects of the

thematic framework subsequently associated with the tradition of the Trojan War may

respond to a much older, extra-Trojan tradition, which was perhaps more coherent

than so far assumed. It is accordingly not only the echoes of discrete mythical motifs

in Greek epic that shall concern us in the following, but also their logic of

combination.

47

48

Joachim Latacz (with comprehensive bibliography) 1988: 14-16.

See especially Georges Dumézil 1966.

15

II. Father Heaven, Heaven’s daughter, and the Divine Twins

The tradition of Helen and the Dioscuri exhibits some archaic features that have

attracted much attention over the years, especially among scholars interested in the

Indo-European aspects of Greek mythology. The issue has been dealt with in different

methodological fashions and scholarly opinions are divided as to the general value

and scope of Indo-European comparanda in the field of myth. Although I principally

remain optimistic to this endeavor, I would agree with some recent critics that such

approaches might run the risk of producing contemporary myths instead of

highlighting old ones.49 I argued above that the notion of an Indo-European “culture”

should be treated with particular caution, not because such a culture could never have

existed, but because its seems futile to reconstruct such a culture on the basis of what

other cultures have passed on as parts of their own heritage.

This chapter is concerned with recurrent themes and onomastic traits in the Greek

mythology that seem to have the same (or a similar) background as the Vedic

treatment of the Sky-god’s (Dyaus) desire for and intercourse with his own daughter

and the consequences of this event. Although the series of successive components are

far from identical in the two traditions, the interfaces (both within and between the

two) are unpredictable to such an extent that is reasonable to assume development

from a shared tradition. I will start from descriptions of the conception and birth of

Helen and the Dioscuri, but instead of moving immediately from this topic to that of

the Vedic Discuri (the A¢vins or Nýsatyas) I intend to look closer at some details in

the thematization of conception and birth as they recur elsewhere in Greek

mythology. I will also pay attention to the figure of Dawn and some of the themes and

figures with which she was associated in Greek mythology. Having done this, I will

present the Vedic and post-Vedic comparanda with regard to two narrative motifs (the

rape of the Dawn-goddess and the wedding Saran‰y¨), explain how these motifs can

be linked together within the Vedic tradition, and subsequently compare the Vedic

and the Greek material.

The rape of Nemesis

The ancestry of Helen and the Dioscuri was rendered differently in early Greek

literature. This is apparent from the scholia to Pindar, Nem. 10,80: “Hesiod, however,

renders Helen (a child) neither of Leda nor of Nemesis, but of a daughter of Okenaos

and Zeus” (oJ mevntoi ÔHsivodo" ou[te Lhvda" ou[te Nemesevw" divdwsi th;n

ÔElevnhn, ajlla; qugatro;" ∆Wkeanou` kai; Diov"). Both Leda and Nemesis could be

regarded as mothers of all three children in two distinct (but similar) versions of the

same tradition. The notion that Leda was the mother to the Dioscuri, but merely

adopted the daughter of Nemesis (as suggested by Apollodorus (Lib. 3,10,7)), need

not be more than an attempt to synthesize two contradictory versions. The idea that

Hesiod rendered Helen a child, not of Nemesis or Leda, but “of a daughter of

Okeanos”, is particularly confusing in the light of the fact that Okenaos was in fact

understood as the father of Nemesis according to some authors (e.g. Pausanias 7,5,3).

If Hesiod really did refer to an “∆Wkeanou` qugavthr” as the mother of Helen it is

therefore likely that he intended Nemesis, but that the scholiast for some reason did

not recognize Nemesis behind this epithet.

49

See especially Lincoln 1999.

16

The story of Zeus and Nemesis in the Cypria seems to be the earliest full treatment

of the conception of Helen. The passage in all likelihood preceded a now lost

treatment of the conception and birth of the Dioscuri. Although the text clearly

indicates that the Dioscuri were conceived earlier (in contrast to some accounts of the

story of Leda and the Swan), it is never explicitly stated that they had another mother.

According to Il. 3,238, Helen had “the same” mother as the Dioscuri (twv moi miva

geivnato mhvthr). There is to my knowledge no explicit reference to Leda as the

mother of Helen in Homer, Hesiod, or the Epic Cycle (the earliest evidence for Leda

as the mother of Helen being Euripides Hel. 16-22, 257-9 and Iph. Aul. 49-51, 794800), but according to the so-called Nekyia (Od. 11,298), Leda is the mother of the

Dioscuri. An early witness of the notion that Leda adopted someone else’s offspring is

Sappho (P.M.G. 166: “once Leda found a dark blue egg” (pota Lhvdan uJakivnqinon

... w[ion eu[ren)). This fragment could be an early testimony of the tradition referred

to by Apollodorus, but it need not derive from exactly the same source as the Cypria.

Although the Cypria does not seem to have contained the tradition that Helen and the

Dioscuri were born from the same egg, such traditions may indeed have existed.50 The

argument that this motif was borrowed from the tradition of Leda51 is inconclusive,

because both traditions (Leda and Nemesis giving birth to an egg after being raped by

Zeus) are so strikingly similar that they are likely to have a common background. I

will content myself with observing that the different versions (Nemesis and Zeus as

the parents of Helen or both Helen and the Dioscuri, Leda and Zeus as the parents of

the Dioscuri and/or Helen, Leda and Zeus as the parents of Polydeuces and Helen,

Leda adopting someone else’s offspring (Helen and/or the Dioscuri))52 may all be old,

but that none of them should take precedence of the other as to the original identity of

the mother. It seems unlikely, however, that both Leda and Nemeis occurred in one

and the same version as victims of rape by Zeus in the form of a swan and then giving

birth to one egg each, whereupon Leda finds and hatches the egg of Nemesis. The

versions in which Leda functions as Helen’s wet-nurse did probably not (at least not

at an early date) contain the story of Leda and the swan. As suggested by a fragment

from Philodemus’ book Peri; eujsevbeia53, antique authors must have noticed that the

two motifs (the metamorphosis and the birth of an egg) were strikingly similar.

Having referred to the story of Nemesis as related in the Cypria (ta; Kuvªpria),

Philodemus states that Zeus “in like manner” (w{sªpºeªïr) transformed into a swan

when he desired Leda. However, this observation rather indicates that Philodemus

was familiar with what happened to be (although he may not have been aware of it

himself) alternative versions of the same tradition, not with discrete motifs in

unconnected traditions or successive motifs in the same version of the tradition.

Apart from the shape-shifting theme, one further detail in the following

description is of some importance for my arguments in the following, namely

that Nemesis’ transformations into different animals could be understood as a

means to avoid incest:

tou;" de; mevta tritavthn ÔElevnhn tevke, qau`ma brotoi`si ...54

E.g. the scholia to Lycophron 88 and to Callimachus, Dian. 232.

Pauly-Wissova, s.v. “Nemesis” 2344.

52

Pauly-Wissova, s.v. “Leda”, 1119f.

53

Wilhelm Cröner 1901: 109.

54

Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker (1849: 514) was the first one to

suggest that Athenaeus may have left out some verses from the Cypria

between the first and the second verse of the quotation. Athenaeus

cited the Cypria because he wanted to show that its author

50

51

17

th;n pote kallivkomo" Nevmesi" filovthti migei`sa

Zhni; qew`n basilh`i tevken kraterh`" uJp∆ ajnavgkh".

feu`ge ga;r oujd∆ e[qelen micqhvmenai ejn filovthti

patri; Dii; Kronivwni: ejteivreto ga;r frevna" aijdoi`

kai; nemevsei: kata; gh`n de; kai; ajtruvgeton mevlan u{dwr

feu`gen, Zeu;" d∆ ejdivwke: labei`n d∆ ejliaiveto qumw`i.

a[llote me;n kata; ku`ma polufloivsboio qalavssh"

ijcquvi eijdomevnh, povnton polu;n ejxorovqunen,

a[llot∆ ajn∆ ÔWkeano;n potamo;n kai; peivrata gaivh",

a[llot∆ ajn∆ h[peiron polubwvlaka. givgneto d∆ aijei;

qhriv∆ o{s∆ h[peiro" aijna; trevfei, o[fra fuvgoi nin.

(Cypria fr. 7, Davies)

“but after them (the Dioscuri) she gave birth to a third (child), Helen, a wonder to

mortals ... Beautiful-haired Nemesis once gave birth to her, having had intercourse

with Zeus, the king of the gods, under harsh violence. She fled because she did not

want to have intercourse with (her?) father Zeus, the son of Kronos; because .

Although the impending rape may certainly be a sufficient cause for Nemesis’ shame

and anger, it seems as if Hugh G. Evely-White, in his translation of the passage (“her

father”), took the reference to Zeus as pavthr in line 5 as implying more than a casual

usage of the epithet “father Zeus”. . This would indeed support my argumentation in

the following, but it cannot be inferred from this or other texts dealing with the

conception of Helen and the Dioscuri that the motif involved incest. True, Nemesis

was explicitly referred to as “Dio;" pai`"” under the name of “Adrasteia” (Euripides,

Rhes. 342), and it is obvious that the Attic tragedians used “Adrasteia” as an epithet of

Nemesis (cf. also Aeschylus, Prom. 93555). However, the paternal genealogy of

Nemesis is quite ambiguous.56 ... It would consequently be too far-fetched to regard

incest as a leading topic in the passage quoted from the Cypria.

Neverthelss, the link between Nemesis and Adrasteia. It is a curious fact is that the

later men of Troy are told to have worshiped the apotheosized Helen as “Adrasteia”57,

which perfectly balances Helen’s association with the word nemevsi" (literally

meaning “retribution” or, more specifically, “righteous anger”) in the Iliad.58 MER

OM VAD NEMESIS OCH HELENA HAR GEMENSAMT. Lindsay point s to

further examples of

represented Nemesis changing into a fish, and the first line would

then clarify who was intended by th;n in the second line. To Welcker,

as I understand his argumentation, a lacuna would make it more

probable that Nemesis was the subject of tevke in the first line,

which also seems to have been the opinion of Athenaeus. It is not

quite clear, however, if the tradition of emending the text with a

lacuna between line 1 and 2 (as passed on in the editions of Bethe,

Allen, and Davies), has been maintained for the reason that Welcker

originally proposed.

55

oiJ proskunou`nte" th;n ∆Adravsteian sofoiv “those who do obeisance to

Adrasteia (lit. ‘that-which –cannot-be-run-away-from’) are wise” (J.

E. Harry 1905: 292). Cf. the expression proskunw` de; th;n Nevmesin at

the end of a letter (Alciphron, Ep. 1,33).

56

H. Herter 1935 (RE XVI 2, 2362).

57

Farnell 1921: 324 and Welcker 1849: 135

58

See discussion in Austin 1994: 43.

18

The stories of Nemesis and Leda are certainly not the only ones in Greek

mythology involving a motif that could be loosely defined as “bestial rape”.59 By

approaching these stories from a sociological perspective, J. E. Robson understands

them as being didactic and symbolic treatments of the attitudes towards marriageable

females and women’s views of marriage and male sexuality that helped to define and

uphold the institutions of the Greek city-state and the Greek world-order.60 They were

focused on the boundaries that should not be crossed by women in order to avoid

rape, but also on the dangers of resisting sanctioned sex. According to Robson, the

“bestial” myth usually takes on one of three typical forms: 1) the god is transformed

into an animal and rapes the girl (Antiope/Zeus, Canace/Poseidon, Dryope/Apollo,

Europa/Zeus, Leda/Zeus, Melantho/Poseidon, Persephone/Zeus, Philyra/Kronos); 2)

the girl is transformed into an animal but is nonetheless raped (Metis/Zeus,

Psamathe/Aeacus, Taygete/Zeus, Thetis/Peleus); 3) both god and girl are changed into

an animal before the sexual act (Asterie/Zeus (or Poseidon), Nemesis/Zeus,

Theophane/Poseidon).61 As exemplified by the stories of Nemesis and Leda, however,

alternative versions of the same tradition need not be restricted to the same group.

Although “rape” is used as a keyword by Robson, caution should be observed insofar

as the word is considered to exclude subsequent consent to sex. The rape of women in

Greek mythology may in fact often, especially if the perpetrator is a god, be classified

as seduction rather than rape, because several accounts of such encounters neither

speak of disgrace or of forcible abduction.62

We may pay further attention to the sociological subtext of this theme by

proceeding from Robson’s (SIDA 77) observation that bestial rape or seduction often

results in heroic offspring. ... Se aäven Deacy’s study in the same book (s. 44).

Dioscuri not really divine (antyds i Nekyia). There are also (and more specifically)

stories in which Zeus or Poseidon beget twins that are subsequently recognized as

progenitors or founders of cities. Some of these are found in the Nekyia (Neleus and

Pelias from Poseidon and Tyro (11,235ff), Amphion and Zethus from Zeus and

Antiope (11,260ff)), others occur elsewhere but nonetheless give an archaic

impression (Aiolos and Boiotos from Poseidon and Melanippe, Minos and

Rhadamanthys (and Sarpedon) from Zeus and Europa). The scheme looks as follows:

1) if Zeus or Poseidon desires a goddess or woman he has a habit of transforming

himself (sometimes in order to conceal their identity), 2) she may change her shape in

order to escape him, 3) she is likely to give birth to a human child or a pair of twins,

4) she sees a reason to hide her offspring or to abandon it, whereupon it is found and

nurtured by someone else (preferably an animal and eventually a shepherd), 5) the

offspring will be distinguished as heroic, as progenitor of a people, or as founder of a

city. It is easy to recognize aspects of such stories as a legitimation of power and as

typical markers of rulership. The first ruler is descended from a god, he is left behind

by his real parents and eventually turns up among humans (often through the medium

of a shepherd) beyond the locus of conception and birth, as if fallen from the sky,

without any predecessors that would otherwise have obstructed the image of a

primordial and incomparable ruler.

As mentioned above, the Nekyia also alludes to the story of Leda and the Dioscuri

(11,298ff), which suggests that the Dioscuri (although here regarded as the sons of

Tyndareus) also conformed to this general pattern, at least in the composition of the

59

For a discussion of this topic, see J. E. Robson 1997: 65-96.

Robson 1997: 82f.

61

Robson 1997: 74.

62

Lefkowiz 1993.

60

19

Nekyia. It is noteworthy that the divine nature of the Dioscuri is not taken for granted

in this passage, but that they rather appear as apotheosized heroes. The topic of

kingship in association with the Dioscuri

Dioscuri, Melanippe, Neleus and Pelias (se övr Preller), Zeus and Antiope

(Apollodorus 3,5,5 (s 337), Zeus and Europa, Poseidon and Mestra (M-W, fr. 43a.5557). Lefkowitz s. 25. Aeschylus Weir Smyth 599-603. Citatet frånb Ion lämpligt

exempel (Lefkowitz 27) of–though it will not happen. Okeanidens transformation

(Lerfkowitz 30). The importance of cattle (Apollodorus 3,5,5 and in the story of

Melanippe Lindsay 119)

It is common to associate kingship with a miraculous conception and adoption

(Arthur). It marks out the king as superhuman and ... andras anspråk på tillhöra

samma ätt.

Apart from this subtext, it would also seem relevant to look at the interface between

such themes and figures that also share features outside this thematic pattern.

This eventually means paying attention to themes and figures that are not directly

associated with the “bestial” myth, but rather with a more complex structure in which

metamorphosis and rape could form an integral part. In doing this, it is my belief that

aspects of older and faded (perhaps even tacit) traditions can be uncovered.

Shape-shifting, rape, and corov"

A key event in the Cyclic tradition, the mating of Zeus and Nemesis is in more than

one way comparable with that of Peleus and Thetis. First of all one recognizes similar

thematic traits in the two stories, especially regarding the function of shape-shifting.

Secondly, the progenies with which the two stories are associated, Helen and

Achilles, have other characteristics in common with regard to their roles in the epic

plot. Both figures are causes for the war and subsequent sufferings on which the

whole tradition is centered, they are a ph`ma (“misery”) for mankind. In this role, the

two figures constitute essential parts in the fulfillment of Zeus’ plan to relieve the

Earth of overpopulation (cf. Cypria fr. 1, Davies).63 The interpretation of Helen and

Achilles as the instruments of the Dio;" boulhv is well-attested in the scholiastic

tradition, and it is possible that a story of over- and depopulation was the source from

which the Cyclic tradition once developed. 64 Another common characteristic of Helen

and Achilles is that they are the only figures in the Iliad who wish for their own

deaths.65 In the light of these facts, it is reasonable to regard the thematic similarities

between the stories of Nemesis and Thetis as an appendage to the structural

agreement of Helen and Achilles.

The story of Peleus and Thetis is already hinted at by the epic poets. The shapeshifting motif is first literary attested with certainty in Pindar and the Tragedians. It is

also seen on three Etruscan bronze tripods from around 520 BC.66 Furthermore, Glenn

W. Most’s attempt to interpret Alcman’s enigmatic cosmogonic fragment (fr. 5, Page)

as an allusion to the myth of Thetis’ metamorphoses suggests that the motif was

63

64

65

66

Mayer 1996: 12.

Mayer 1996: 1ff.

Mayer 1996: 12.

Krieger 1975: 10f.

20

already a focus of philosophical speculation in the 7th century. As the story is told by

Pindar and others following upon him, Zeus and Poseidon, both desiring the Nereid

Thetis, are warned by Themis that the son of Thetis will be more powerful than his

father. It is decided that Thetis is to be given as wife to the mortal Peleus. Peleus

steals upon Thetis on a full moon evening, but in order to win her he has to hold her

fast as she assumes different forms (fire, snake, lion, etc.). According to a Papyri from

Herculaneum (fr 2, Davies), both Hesiod and the author of the Cypria handed over a

slightly different version of the story, in which Zeus swears that Thetis has to become

the wife of a mortal since she has avoided marriage with him (in order to please

Hera).

Some modern commentators draw the conclusion that Thetis and the other Nereids

were dancing at the event of the rape.67 Although this would indeed apply to the

general literary and artistic characterization of the Nereids, I have not found explicit

references to dancing in the sources containing the story of Peleus and Thetis.

KORRIGERA DETTA !!!! Nevertheless, the possibility that Thetis and the other

Nereids were performing a ring-dance at a sacred dancing-ground (corov") at the time

of the rape may be considered relevant for the following discussion. Indirect support

for this possibility is found in literary descriptions of the Nereids, occasionally also as

they appear at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (cf. Euripides, Ion 1078ff, Iph. Taur.

427ff, Iph. Aul. 1055, Himerius (Eclogue XIII, 21). In all these passages, the keyword

is either the verb corevw or the noun corov". There are, furthermore, icongraphic data

suggesting that the rape took place at a dancing-ground or while the Nereids were

dancing... In Greek epic, the corov" is not only the locus of sexual arousal and rape

(cf. the examples listed in Lawler 1964: 42f.68), but it is also a place particularly

associated with the goddess Eos and her supposed hypostasis Aphrodite. D. D.

Boedeker has treated this topic in detail in her study of Aphrodite’s entry into Greek

epic.69 She argues that the word corov" refers to a dancing-ground that was also a type

of cult place inherited from pre-Greek religion. This cult was aimed at goddesses of

fertility and growth, which in Greek society needed not be of cthonic origin. Boedeker

also makes clear that the word, from the point of view of both etymological and

philological evidence, was associated with the abode of the Sun and Dawn. According

to Boedeker, the goddess Eos (and her Indo-European precursor) in fact constitutes an

underlying impetus of the thematic associations of corov". Cf. Boedeker s. 61. Eos is

neither raped, nor does she shift shape. There are several depictions of Eos pursuing

mortals, her arms outstreched etc.

The figures and stories presented in this chapter seem directly or indirectly associated

with the corov". It is in fact more than the locus or background of some typical

mythical events. It is a nexus ... Greek and Vedic. Apart from the interfaces of Greek

and Vedic as regards the Dawn-goddess and the dancing-ground discussed so far, I

see here another possible link between the two traditions, namely the fact that the

Vedic Dawn-goddess is the subject of rape in the context of theriomorphic shapeshifting. Consequently, the corov" as a locus of sexual arousal and rape may be

regarded as a “missing link”, as the remaining trace of traditions that were either lost

67

Cf, for instance, M. Meyer (1937) (RE VI A, 209): “in einer

Vollmondnacht, wie sie (Thetis) mit ihren Schwester-Nereiden den

Reigen tanzt, lauert er (Peleus) ihr auf, springt hervor, um sie zu

ergreifen.”

68

69

Boedeker 1974: 43-63.

21

or transformed beyond recognition in Greek mythology. We are only able to retrieve

these traditions if they can be shown to havING survived in societies sharing parts of

the same heritage as the Greeks.

END UP DAWN. FOLLOWED BY THE NATURE OF DAWN AND HELEN

Helen’s role as sister of the Dioscuri and daughter of Zeus and Leda/Nemesis would

not give us any obvious reason to compare her fate with that of her mother, but a

closer look at the features that she shared with other females in Greek mythology

brings her somewhat closer to the typology of rape and shape-shifting.

Tacitus Alcis (möjl jfr h2elk/h2leks (Gr. alkÿ´/aléxþ, rák˜ati), Alkinóos,

“näsetymologin” anspelning på den i RV 2,39,6): ný´seva nas tanúvo rak˜itý´rý. “as the

noose (be) the protectors of our body!” The simile seems a little far-fetched, so one

may assume that the poet rather wanted ný´seva nas to serve as an echo of the name

Ný´satyau. These would then be the rak˜itý´rý (nom.sg. *h2leks?-tór) of the body.

Stesicorus 209 not 3: hänv. till Od. 15,160ff the portent of an eagle clutching a goose.

Alkiman om ytterligare ett försök att våldta Helena, Lindsay 116 (hänv. Alkman

(Page 6). Slutet av Aristofanes Lysistrata visar att Helena ledde den dansande

flickkören i Sparta (Lindsay 118). Helena som khoragos i flicksången (Lindsay 119).

Melanippe (Lindsay 96) föder tvillingar efter att ha blivit våldtagen av Poseidon). Se

även Lindsay 119 och kopplingen mellan Helena och historien om Mellanippe. We

may recall that at least in late times the poloi of the Leukippides were linked with a

boy priest apparently called bouagor or ox-herd; Hesychios mentions the ox-plough,

poupharon; anmd the twins of the black mare, Mellanippe, were connected with bull

and cow. But even if Helen was not Aoits, the Maidensong certainly shows a sort of

dance-song with which she was associated at Sparta and in which she acted as

daimon, as spirit choragos.

Poseidon avlar tvillingar enl. fast mönster. Se Preller Gr. Myth. 588. Poseidon

dyrkades under namnet Enipeus i Miletos (se Preller 579 not 2). Ang. kultnamnet

Enipeus, jfr Od. 5,446 seeking to escape the threats of Poseidon.

Tvillingar som grundar städer (eller uppfattas som stamfäder) efter att ha avlats av

Zeus eller Poseidon, företrädesvis i djurform, ammas av djur. Remus och Romulus?!

Puhvel tar fel när han försöker ignorera de grekiska sagorna. Exempel hos Preller 588.

Att detta var en topos redan hos Homeros framgår av Od. 11,235ff.

Poseidon och nereiden Ampitryon Preller 596f, även hon våldtas när hon danser.

Poseidon avlar Fajakernas konung Preller 622.

The name reconstructed as swelene by Skutsch and claimed to have merged with

Helen really looks very much as Selene. This would mean that there were two

goddesses, at least in Sparta, Welene and Selene, both derived from *Swelene. This

seems rather unlikely. Corinna (gr.Lyr IV s. 59). Aos drew the moons holy

light.Alkman: Selana och daggen, Zeus dotter s. 435.

F. Zeitlin “configurations of rape in Greek myth” (in Tomaselli, S. ed. Rape), Keuls

Reign of the Phallus (s.50).

22

Thetis dansar? Alkman fr. Most s. 16. Pind Isth. 8 fullmåne fotnot. Helen, Aphrodite,

Thetis kan alla ses som manifestationer av Eos. Slatkin om Memnon 23. Slatkin 27.

Thetis egen utsaga i Il 18,429ff. Zeus vill själv gifta sig med henne Cypria 4.

Jfr Mosts (s. 6) didaktiska aspekter på Alkman med Robson

Varför inte digamma i namnet Helena (s. 396) hos Alkman när ex. wékaton (s. 426)?

från hekás afar, wépÿ s. 424, wepéþn 416

Fajakernas hem khoros Boedeker 60

Hästoffer Prajapati. Mortal and god Vivasvat Peleus

eidolon redan hos Hesiodos West fr. 358

Eos/Thetis. Slatkin: 31 their relationship is structurally homologous, not historical.

formulaics Thetis tidig s. 32.

Although this name . Clader Euripides Rhes 342.

Pauly Leda1110. Schol. Eur. Or. 1371.

RESTER

... Carpentry (its implications, weave poikelom) ... Metrics (controversial, Nagy and

Watkins) ... Bipartite formulas (några exempel) .... Patterns of mythical speeech and

(Hesiod dierkhetai, orthos omikhein) ... The pantborheon (Dyaus/Varuna, metaphors

for the mantle of the nocturnal sky)... The concept of the hero (exempel i West 1988).

SPEKULATION: Zeus decision to bring about the Trojan War, his boule (cf. Myth

of Yama) (West JHS 1988, 156. R. Köhler, Rh. Mus. xiii (1858) 316f. Pisani 156f., W

Kullmann, Philologu xcix 1955, 186). Om khoros som våldtäktsscen i assoc. med

Afrod. och Helena. Läs Boedeker, 43ff. Od. m1-4 Eos och Khoros. Boedeker 59.