* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Number Needed to Treat: an Important Measure for the Correct

Survey

Document related concepts

Psychedelic therapy wikipedia , lookup

Clinical trial wikipedia , lookup

Orphan drug wikipedia , lookup

Polysubstance dependence wikipedia , lookup

Drug design wikipedia , lookup

Atypical antipsychotic wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Drug discovery wikipedia , lookup

Prescription drug prices in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacognosy wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

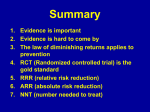

Editorial DOI: 10.5455/bcp.20150318073223 Number Needed to Treat: an Important Measure for the Correct Assessment of Clinical Significance Mesut Cetin1, Selim Kilic2 Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2015;25(1):1-3 Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is a concept first found in papers published by Laupacis et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1988. NNT is the average number of patients who need to be treated to prevent one additional bad outcome (e.g. the number of patients that need to be treated for one to benefit compared with a control in a clinical trial)1. This measure assessing the clinical significance of any kind of intervention has since been applied with increasing frequency. This concept is frequently used in psychiatry, especially when comparing the efficacy and effectiveness of drugs and is seen as an important indicator to demonstrate the advantage of a new drug over a standard or reference drug and/or placebo treatment2-5. In addition to NNT, there are two more concepts in use for the comparison of drug efficacy and/or effectiveness namely, “Absolute Risk Reduction” (ARR) which is the efficacy of drug 1 – the efficacy of drug 2 and “Relative Risk Reduction” (RRR) which is the efficacy of drug 1 / the efficacy of drug 26-8. Thus, ARR measures the difference in efficacy between two drugs and RRR the ratio between the efficacies of two treatments. Given that, of these two measures, RRR may make the effect size appear higher than it is in reality, it has been established that using NNT, which is related to ARR (NNT=1/ARR), allows a more accurate assessment of the effect size). In very large samples, the p value, which is affected not only by effect size but also by sample size, can be very close to zero (p<0.001) even though there is no clinically significant difference. After all, the p value ascertains that the difference found in the comparison is statistically significant, i.e., not accidental. It is thus possible that a statistically significant p value may be wrongly interpreted as implying that there is a clinically significant difference. By contrast, the NNT value, which is unaffected by the sample size affecting the p value, is a suitable measure to demonstrate and interpret clinical significance10-11. The closer the NNT value is to 1, the more effective is the drug. On the other hand, drugs can lead to undesirable side effects in clinical application. To give some examples of commonly found side effects, antidepressants can lead to weight gain, sedation, and sexual side effects2 and antipsychotics used in patients suffering from schizophrenia or bipolar disorder can provoke extrapyramidal side effects, weight gain, an increase in prolactin or a QTc prolongation in the ECG12-14. To quantify the undesirable side effects of clinically applied drugs, the concept of “Number Needed to Harm” (NNH) has been developed, which is defined as the average number of people who would need to be treated over a specific period of time before one bad outcome of the treatment would occur. NNH is a concept showing how many members of a population taking a given drug in the course of their treatment are likely to suffer from side effects. The following example will explain the concept. Out of 100 patients taking drug A, 30 show weight gain as a side effect, while of 100 patients using drug B, only 10 develop weight gain; in drug A, the undesired result affects 30%, in drug B 10%, leading to an NNH value of 1/ (0.30-0.10)=5. That is to say, in order to Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni, Cilt: 25, Sayı: 1, 2015 / Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vol: 25, N.: 1, 2015 - www.psikofarmakoloji.org 1 Number needed to treat: an important measure for the correct assessment of clinical significance demonstrate the side effect of weight gain to be higher in drug A than in drug B or vice versa, to show the effect to be lower in drug B than in drug A, at least 5 patients need to be treated. In that case, from the perspective of the side effect of weight gain, drug B is superior to drug A. As explained above, the desired outcome is an NNT value close to 1, showing the drug’s efficacy and effectiveness, and a very large NNH value, heading towards infinity, showing that the side effects of the drug are very small. As a concrete example, in a meta-analysis conducted by Stewart et al. to assess the usefulness of antidepressants in cases of non-severe major depression, the authors reported that an NNT between 3 and 8 was sufficient evidence to recommend the studied antidepressants for therapeutic use15. In another study assessing the efficacy of some antipsychotics used in schizophrenic patients to prevent relapse, NNT values between 2 and 5 have been reported as an indicator for a medium and broad effect size16. A review made by Citrome mentions one study comparing asenapine against a placebo in schizophrenic patients. With asenapine (10mg twice daily), an NNH of 20 was found for oral hypoesthesia; with a dose of 5mg asenapine twice daily, the NHH was 20 for hypoesthesia in the mouth and 13 for somnolence. In patients suffering from bipolar disorder, compared to placebo, asenapine at 5-10mg twice daily resulted in NNH values of 6 for somnolence, 13 for dizziness, 20 for extra-pyramidal symptoms other than akathisia, and 25 for increased weight14. In a paper published by Srivastava and Ketter, large-scale, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in acute mania and bipolar depression were assessed with regard to the NNT for response to treatment and NNH for sedation and weight gain. They found that lithium, in comparison with other FDAapproved drugs, showed a similar efficacy (NNT 4 vs. 4-8) but a significantly lower sedation (NNH 27 vs. 5-17). A recently published study by Ketter et al. 2 assessed old and new anti-depressants, using mu l t i - c e n t e r, r a n d o m i z e d , d o u bl e - bl i n d , placebo-controlled studies and meta-analyses using NNT values for response to treatment and NNH for side effects. There are mainly two FDAapproved therapies for bipolar depression, olanzapine/ fluoxetine combination (OFC) and quetiapine monotherapy (QTP). For the response efficacy, OFC resulted in NNT=4 and QTP NNT=6, while side effects of weight gain (OFC: NNH=6) and sedation/somnolence (QTP: NNH=5) were noted. In another example, the antipsychotic lurasidone, recently approved in the US, showed a response NNT=5 for monotherapy and NNT=7 as adjunctive, with NNH=16 for nausea (adjunctive) and NNH=15 for akathisia (as monotherapy), thus being effective as well as better tolerated17. Which of these values do we take into consideration, and are there optimal values for each of these measures? The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved drugs for the pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder with NNT values in the single figures, below ten (with an advantage over placebo of more than 10%), and there are studies reporting that the clinical efficacy of drugs with NNT values below ten have been accepted as significant11,12,19,20. While there is a greater consensus in the studies regarding acceptable NNT values, it has been reported that the acceptability of NNH values varies particularly depending on the outcome of undesirable side effects. Therefore, in more acute severe illness presentations, drugs with high therapeutic success may be chosen even though their side effects are greater, while in chronic, mild to medium cases even less efficacious drugs with fewer side effects may be preferred. In the light of this information, it is therefore suggested that clinicians, when deciding about the choice of therapy, take both efficacy and tolerability into consideration, looking not only at the NNT values regarding the effect, but also at the NNH to estimate the occurrence of various side effects, thereby making careful, individualized, patientcentered decisions. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni, Cilt: 25, Sayı: 1, 2015 / Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vol: 25, N.: 1, 2015 - www.psikofarmakoloji.org Cetin M, Kilic S 1 Correspondence Address: Prof. Dr. Mesut Cetin, Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni-Bulletin of Clinical M.D., Professor of Psychiatry, Editor -in- Chief, GATA Haydarpasa Training Hospital, Department of Pychopharmacology, GATA Haydarpasa Training Psychiatry, Uskudar, 34668, Istanbul-Turkey Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, Istanbul-Turkey Phone: +90-216-464-2888 Email address: [email protected] 2 Prof., M.D., Department of Epidemiology, Gulhane School of Medicine, Ankara-Turkey References: 1. Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1728-33. [CrossRef] 2. Srivastava S, Ketter TA. Clinical relevance of treatments for acute bipolar disorder: balancing therapeutic and adverse effects. Clin Ther 2011;33(12):B40-8. [CrossRef] 3. Cetin M, Acikel CH. In the perspective of meta-analyses: are all of the antidepressants similar? Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni - Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2009;19(2):87-92. (Turkish) 4. Cetin M, Kilic S. How to comprehend the recent metaanalyses conducted on typical and atypical antipsychotics? Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni - Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2009;19:(1)1-4. (Turkish) 5. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2011;37(3):619-30. [CrossRef] 6. Smith EG, Søndergård L, Lopez AG, Andersen PK, Kessing LV. Association between consistent purchase of anticonvulsants or lithium and suicide risk: a longitudinal cohort study from Denmark, 1995-2001. J Affect Disord 2009;117(3):162-7. [CrossRef] 7. Gao K, Ganocy SJ, Gajwani P, Muzina DJ, Kemp DE, Calabrese JR.A review of sensitivity and tolerability of antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: focus on somnolence. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(2):302-9. [CrossRef] 8. Correll CU, Kishimoto T, Nielsen J, Kane JM. Quantifying clinical relevance in the treatment of schizophrenia. Clin Ther 2011;33(12):B16-39. [CrossRef] 9. Citrome L. Relative vs. absolute measures of benefit and risk: what’s the difference? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;121(2):94-102. [CrossRef] 10. Citrome L. The Tyranny of the P-value: effect size matters. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni - Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2011;21(2):91-2. [CrossRef] 11.Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67(5):407-11. [CrossRef] 12.Citrome L. Adjunctive aripiprazole, olanzapine, or quetiapine for major depressive disorder: an analysis of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Postgrad Med 2010;122(4):39-48. [CrossRef] 13. Correll CU, Sheridan EM, DelBello MP. Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: a comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 2010;12(2):116-41. [CrossRef] 14.Citrome L. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved sublingually absorbed second-generation antipsychotic. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63(12):1762-84. [CrossRef] 15.Stewart JA, Deliyannides DA, Hellerstein DJ, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW. Can people with nonsevere major depression benefit from antidepressant medication? J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73(4):518-25. [CrossRef] 16. Gopal S, Berwaerts J, Nuamah I, Akhras K, Coppola D, Daly E, Hough D, Palumbo J. Number needed to treat and number needed to harm with paliperidone palmitate relative to longacting haloperidol, bromperidol, and fluphenazine decanoate for treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2011;7:93-101. [CrossRef] 17.Ketter TA, Miller S, Dell’Osso B, Calabrese JR, Frye MA, Citrome L. Balancing benefits and harms of treatments for acute bipolar depression. J Affect Disord 2014;169(Suppl 1):S24-S33. [CrossRef] 18.Citrome L. Lurasidone for the acute treatment of adults with schizophrenia: what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 2012;6(2):76-85. [CrossRef] 19.Ketter TA, Citrome L, Wang PW, Culver JL, Srivastava S. Treatments for bipolar disorder: can number needed to treat/harm help inform clinical decisions? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;123(3):175-89. [CrossRef] 20.Popovic D, Reinares M, Amann B, Salamero M, Vieta E. Number needed to treat analyses of drugs used for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:657-67. [CrossRef] Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni, Cilt: 25, Sayı: 1, 2015 / Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vol: 25, N.: 1, 2015 - www.psikofarmakoloji.org 3