* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

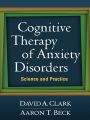

Download Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders

Pyotr Gannushkin wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

Narcissistic personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Spectrum disorder wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Selective mutism wikipedia , lookup

Obsessive–compulsive disorder wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Asperger syndrome wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Panic disorder wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Treatments for combat-related PTSD wikipedia , lookup

Anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup