* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Trends in Enteric Disease as a Cause of Death in the United States

Survey

Document related concepts

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Bioterrorism wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Neglected tropical diseases wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

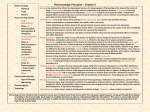

American Journal of Epidemiology Copyright © 2003 by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health All rights reserved Vol. 157, No. 1 Printed in U.S.A. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwf172 Trends in Enteric Disease as a Cause of Death in the United States, 1989–1996 Christina A. Peterson1,2,3 and Rebecca L. Calderon2 1 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. National Health and Environmental Effects Laboratory, Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, NC. 3 Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. 2 Received for publication December 13, 2001; accepted for publication July 24, 2002. The authors examined rates of and trends in enteric disease as a cause of death in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics Multiple Cause of Death databases for 1989–1996 were analyzed for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes for gastroenteritis due to infectious agents and codes describing illness with other enteric pathogens. The highest rates of death related to enteric diseases were seen among people older than 75 years, followed by children under 1 year of age. Rates increased markedly over time in the 65- to 74-year age group for bacterial enteric pathogens and in the 35- to 44-year age group for viral enteric pathogens. Enteric diseases were the underlying cause of death for an average of 2,740 deaths during each year of this study, and the rate of death due to enteric-related disease is increasing. gastroenteritis; intestinal diseases; mortality Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICD9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; MCD, multiple cause of death; RR, relative risk. sification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), code group 002). By 1920, typhoid and paratyphoid fever death rates had been reduced more than threefold to only 7.6 deaths per 100,000 population, partly because of disinfection and filtration of community water supplies. Deaths from typhoid and paratyphoid fever dropped below 0.05 per 100,000 population in 1953 and have remained at that level since then (5). During that same time span, deaths due to gastritis, duodenitis, enteritis, and colitis dropped from a high of 142.7 per 100,000 population in 1900 to less than 1 per 100,000 population beginning in 1968 (and continuing through 1996) (5). Thus, the impact of enteric diseases on mortality has been greatly reduced over the last century. However, the proportion of Americans who are at high risk for severe enteric disease because of low immunity or advanced age is increasing each year. Using national mortality data, we made a quantitative estimate of the numbers of endemic and epidemic deaths related to microbial-enteric disease in the United States from 1989 to 1996. Specific goals of this study were to estimate agespecific reporting rates of microbial-enteric diseases as Enteric diseases continue to contribute to the overall burden of human disease. In vulnerable populations such as young children, the elderly, and the immunocompromised, enteric diseases are especially prevalent and more often result in serious outcomes. It has been estimated that the cost of acute intestinal infections in the United States, including medical costs and lost productivity, exceeds $20 billion annually (1, 2). A recent report from the FoodNet surveillance system estimated that there are 76 million cases of foodborne disease each year in the United States (3). Many foodborne pathogens are enteric in origin, but these infections represent a fraction of all enteric infections, which may also occur through waterborne or person-to-person transmission. During the 20th century, rates of death due to enteric diseases plummeted, largely because of disinfection of drinking water. In 1900, 8.3 percent of all deaths were due to the broad cause of gastritis (including diarrhea, enteritis, and colitis), but by 1990 all infectious diseases (respiratory as well as gastrointestinal) accounted for only 1.8 percent of deaths (4). In 1900, 31.3 deaths per 100,000 population were due to typhoid and paratyphoid fever (5) (International Clas- Reprint requests to Dr. Rebecca L. Calderon, National Health and Environmental Effects Laboratory, US Environmental Protection Agency, MD-58C, Research Triangle Park, NC 27711 (e-mail: [email protected]). 58 Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 Enteric Disease as a Cause of Death 59 causes of death and to investigate regional and etiologic trends in reporting rates of these diseases in relation to deaths in the United States. MATERIALS AND METHODS Data The National Center for Health Statistics Multiple Cause of Death (MCD) data sets (6–13) include data on all recorded deaths that occur in the United States, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the US Virgin Islands within specified years. Each record includes information from the decedent’s death certificate about the underlying cause of death, multiple conditions that contributed to the death, and the place and date of death, as well as demographic data on the decedent. Each record may contain up to 20 causes of death that were coded using the ICD-9. For the years 1989–1996, every recorded death in the United States was included within these data sets. Deaths that occurred outside of the 50 states, such as those in Guam, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, were excluded from this analysis. Two sets of codes on conditions considered contributing causes of death are included for each data record in the MCD files. The original death certificate coding is preserved in the entity-axis codes, while the record-axis codes have been edited by the National Center for Health Statistics to eliminate contradictions and to define the condition most precisely within the limitations of ICD-9 coding and the available medical information on the death certificate (6). Record-axis codes are used by the National Center for Health Statistics for the published MCD statistics. The ordering of codes within each record is not the same as it appeared on the death certificate, and this should not be considered relevant information. Record-axis codes represent the most meaningful codes for the reported condition, but some detail has been removed from the entity code for that record. ICD-9 category titles apply directly to recordaxis codes. For example, a decedent with entity codes ICD-9 571.5 (cirrhosis of the liver without mention of alcohol) and ICD-9 303 (alcohol dependence syndrome) would have those codes replaced in the record-axis data by ICD-9 571.2 (alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver) (6). This analysis used the record-axis codes from the MCD files. Poisson regression was used to estimate relative risks for possible predictors of enteric disease, including age group, sex, race, and US Census region. Analysis The MCD data were categorized by decedent age, race, and US Census region and then analyzed for reports of enteric disease. Four broad ICD-9 code categories based on the etiologic agents responsible for disease were used in the analysis. “Bacterial deaths” include decedents whose death certificates mentioned certain ICD-9 codes in the 001–004, 008, and 041 groups; “viral deaths” include decedents whose death certificates mentioned certain ICD-9 codes in the 8.6, 045, 047–049, 070, 074, 079, 138, and 139 groups; “protozoal deaths” include decedents whose death certificates Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 mentioned certain ICD-9 codes in the 006, 007, and 127 groups; and “other microbial deaths” include decedents whose death certificates mentioned certain ICD-9 codes in the 008, 009, and 139 groups. The category “all enteric disease deaths” includes the sum of the bacterial, viral, protozoal, and other microbial categories. Each record was examined for the presence of any of the designated ICD-9 codes in any position (from the underlying cause of death through the 20th contributing cause of death) within the record. An indicator variable was indexed for each type of microbe for each diagnosed disease. These cases were then summed within the microbial categories to create national estimates of the number of bacterial, viral, protozoal, and other microbial diseases that contributed to deaths. Each enteric diagnosis was counted separately, so that the number of diseases could be estimated. For example, if an individual died with an intestinal Campylobacter infection (ICD-9 code 8.43) as well as giardiasis (ICD-9 code 7.1) and hepatitis A (ICD-9 code 70.1), the individual would be counted under each of the three enteric diseases rather than as just one decedent with multiple diseases. The MCD data do not include population figures, so the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program (14) was used to obtain population denominators for calculation of region-, age-, and race/ethnicity-specific rates. For these analyses, the “White” ethnicity category includes nonHispanic Whites and the “Black” category includes nonHispanic Blacks. The “Other” category includes Hispanics and all other reported racial and ethnic designations, including but not limited to Native Americans, Aleuts, Inuits, Pacific Islanders, and Asians. Age- and race-specific rates of death related to enteric disease were calculated by summing the diseases in each category and then dividing by the corresponding population total. For example, the number of reported bacterial enteric diseases contributing to the deaths of Black children under 5 years of age in 1996 was calculated from the MCD database (number of deaths = 10). This value was then divided by the estimated number of Black children under age 5 years in the United States in 1996 from the US Census data (population = 2,770,999) and multiplied by 100,000 to arrive at a rate of 0.36 deaths due to bacterial enteric diseases per 100,000 population. Thus, the specific death rate for Black children under 5 years of age is 0.36 deaths per 100,000 population (10 deaths × 100,000/2,770,999 population = 0.36 per 100,000). For each death, the underlying cause and up to 20 contributing causes were analyzed. During the years studied, no decedents had more than 15 causes of death included in their record. The majority of decedents with an enteric disease had either one or two enteric diseases listed as causes of death, and no decedents had more than four enteric diseases listed as causes of death during the study years (table 1). RESULTS Examination of the MCD data from 1989–1996 indicated a steady increase in the rate of reported deaths associated with enteric viral diseases (figure 1). During the same period, reports of bacterial and other microbial enteric 60 Peterson and Calderon TABLE 1. Frequency and prevalence of enteric disease as a contributing cause of death in the United States, 1989–1996 No. of deaths, according to no. of enteric disease diagnoses Year(s) One diagnosis Two Three Four diagnoses diagnoses diagnoses Total no. of deaths % of decedents whose death was related to enteric disease 1989 1,319 1,768 19 0 3,106 2,153,859 0.14 1990 1,463 1,792 18 0 3,273 2,151,890 0.15 1991 1,757 2,020 20 0 3,797 2,173,060 0.18 1992 2,114 2,231 23 0 4,368 2,179,187 0.20 1993 2,801 2,739 34 0 5,574 2,271,947 0.25 1994 3,375 3,402 38 0 6,815 2,282,288 0.30 1995 3,870 3,843 46 1 7,760 2,315,251 0.34 1996 1989–1996 % of total no. of decedents with enteric disease diagnoses 4,308 4,247 32 2 8,589 2,318,212 0.37 21,007 22,042 230 3 43,282 17,845,694 0.24 49 51 1 0 diseases as causes of death approximately doubled (bacterial: 0.37 per 100,000 in 1989, 0.73 per 100,000 in 1996; other microbial: 0.30 per 100,000 in 1989, 0.56 per 100,000 in 1996), while reports of deaths associated with protozoal diseases remained nearly constant at approximately 0.01– 0.02 reports per 100,000 population. Reports of enteric viral FIGURE 1. 1996. Total no. of deaths related to enteric disease disease as a cause of death increased approximately threefold over the study period, from a minimum of about 1.3 per 100,000 in 1989 to a maximum of just over 3.5 per 100,000 in 1996. Between 1989 and 1996, the fraction of deaths related to enteric diseases of any etiology increased each year, with an average percentage increase of 116 percent. Rate of reporting of enteric disease as a contributing cause of death in the United States, by year and microorganism group, 1989– Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 Enteric Disease as a Cause of Death 61 FIGURE 2. Rate of reporting of bacterial and viral enteric diseases as contributing causes of death in the United States, by age, 1989–1996. Age-specific rates The rate of reported deaths associated with bacterial diseases increased with age beginning with the 55- to 64year age group and increased sharply in the older age categories (figure 2). Infants and children under 5 years of age experienced rates similar to those of people aged 25–45 years and higher than those of people aged 5–24 years. Reported rates of bacterial disease death for the older age categories were higher each year than in the preceding year. Viral enteric disease was also more frequently reported as a cause of death in the oldest age categories, but the increase in reports of viral enteric disease as a cause of death started at a younger age level than that for reported deaths associated with bacterial disease (figure 2). The rates of reported death associated with viral disease began to increase with the 35to 44-year age group, while bacterial disease death reports began to increase with the 55- to 64-year age group. In the most recent years, the rise in the number of reported deaths associated with viral enteric diseases was most rapid among decedents aged 65 years or more, while 35- to 64-year-olds experienced a smaller increase, and the rates of viral enteric disease for people younger than age 34 years at death were nearly constant (figure 3). Age- and race/ethnicity-specific rates In general, enteric infections were reported more frequently as a cause of death for Blacks than for persons of other racial/ethnic categories (figure 4). The disparity among death rates in the under-5 age category was due to Black Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 children and infants dying with other microbial infections at a rate nearly four times that of children in other racial/ethnic categories (annual average rate of reporting: Black = 5.8 per 100,000 population; White = 1.6 per 100,000 population; Other = 1.7 per 100,000 population). In the oldest age category, the racial/ethnic differences in rate are driven by the rates of bacterial infection: Black elderly suffer from enteric bacterial infections more than three times as often as White decedents and five times as often as Other decedents (annual average rate of reporting of bacterial enteric infection as a contributing cause of death: Black = 16.9 per 100,000 population; White = 5.2 per 100,000 population; Other = 3.0 per 100,000 population). Etiologic trends A frequency analysis of the ICD-9 codes listed for each death in each microbial category indicated that the increased rates were due to increased rates of reporting within certain code groups rather than to an increase in reports of all enteric diseases. For the bacterial pathogens, the increase in reports was driven by an increase in the 008 codes (intestinal infection due to other organisms), along with a slight increase in the 041 codes (bacterial infection in conditions classified elsewhere). The most commonly reported subcategory within the bacterial disease diagnoses was the 008.4 code, which includes Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Campylobacter, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Clostridium difficile, as well as other anaerobes and Gram-negative bacteria. Within the viral category, the increase was due almost completely to a rise in reports of the 070 code (viral hepatitis). 62 Peterson and Calderon FIGURE 3. Rate of reporting of viral enteric disease as a contributing cause of death in the United States, by age, 1989–1996. FIGURE 4. Mean annual rate of reporting of all microbial enteric disease as a contributing cause of death in the United States, by age and ethnicity, 1989–1996. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 Enteric Disease as a Cause of Death 63 TABLE 2. Relative risk associated with Poisson regression model parameters for enteric diseases as causes of death in the United States, 1989–1996 All enteric infections Predictor Bacterial enteric infections 95% CL* RR* Viral enteric infections 95% CL RR Lower Upper Protozoal enteric infections 95% CL RR Lower Upper Other enteric microbial infections 95% CL RR Lower Upper 95% CL RR Lower Upper Lower Upper Age group (years) <5 1.18 1.14 1.23 1.48 1.31 1.67 0.25 0.23 0.27 0.30 0.16 0.56 11.34 10.56 12.18 5-24 1.13 1.07 1.21 2.17 1.82 2.59 0.93 0.86 1.00 1.43 0.84 2.45 2.63 2.25 3.07 25-34 1.00 0.96 1.04 1.68 1.48 1.90 0.83 0.79 0.87 2.37 1.77 3.16 2.21 1.98 2.47 55-64 1.02 0.99 1.05 1.58 1.44 1.74 0.99 0.96 1.02 0.46 0.32 0.66 0.94 0.84 1.04 65-74 1.03 1.01 1.06 2.28 2.11 2.46 0.94 0.91 0.96 0.23 0.15 0.35 1.12 1.02 1.22 ≥75 0.99 0.96 1.01 4.62 4.31 4.94 0.62 0.61 0.64 0.39 0.29 0.53 1.95 1.81 2.10 Other 0.98 0.62 1.58 1.02 0.89 1.17 1.00 0.95 1.05 1.19 0.67 2.09 0.87 0.76 1.00 0.97 0.95 0.99 1.22 1.15 1.29 0.88 0.85 0.90 1.19 0.92 1.55 1.19 1.13 1.25 Northeast 0.98 0.96 1.01 1.98 1.87 2.09 0.82 0.80 0.84 0.63 0.46 0.87 1.02 0.96 1.09 Midwest 0.97 0.95 0.99 1.40 1.32 1.49 0.86 0.84 0.89 0.89 0.66 1.20 1.23 1.15 1.31 South 1.02 0.99 1.04 1.33 1.25 1.41 0.95 0.93 0.97 0.85 0.65 1.10 1.16 1.10 1.23 0.96 0.94 0.98 0.91 0.88 0.95 0.98 0.96 1.00 1.57 1.25 1.98 0.91 0.88 0.95 0.99 0.99 1.00 0.97 0.97 0.98 1.00 1.00 1.01 0.88 0.84 0.92 0.98 0.97 0.99 35-54† Race Black White† Region West† Gender Male Female† Year * RR, relative risk; CL, confidence limits. † Reference category. Rates of reported hepatitis infection and intestinal bacterial infection contributing to death both increased more than threefold over the study period (hepatitis range: from 0.46 reports per 100,000 population in 1989 to 1.68 reports per 100,000 population in 1996, a 363 percent increase; code 008.4 intestinal bacterial infection range: from 0.076 reports per 100,000 population in 1989 to 0.32 reports per 100,000 population in 1996, a 429 percent increase). During that same time, the fraction of all bacterial codes belonging to the ICD-9 code 008.4 increased by 220 percent (from 20 percent of all deaths related to enteric bacterial disease in 1989 to 44 percent in 1996). Risk factor modeling Poisson regression analysis was performed for each microbial category separately and then for all enteric infections together. Age group, gender, race, and region were included as categorical predictors, and year was entered into the models as a continuous variable (table 2). In every case, age categories were the most significant predictors of risk, with different age groups being at highest risk for different types of pathogens. Children under age 5 years were at highest risk of death due to other microbial infections (relative risk Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 (RR) = 11.34, 95 percent confidence interval (CI): 10.56, 12.18) and all enteric infections combined (RR = 1.18, 95 percent CI: 1.14, 1.23), while people over age 75 years were at highest risk of death due to bacterial enteric infections (RR = 4.62, 95 percent CI: 4.31, 4.94). Children under age 5 years and infants had the lowest risk of death due to viral enteric pathogens (RR = 0.25, 95 percent CI: 0.23, 0.27) as compared with the 35- to 54-year-old reference group. Risk of death due to protozoal enteric infection was high in both persons aged 5–24 years (RR = 1.43, 95 percent CI: 0.84, 2.45) and persons aged 25–34 years (RR = 2.37, 95 percent CI: 1.77, 3.16), though small numbers of deaths in this microbial category led to imprecise estimates with wide confidence intervals. DISCUSSION Enteric disease burden in the US population We estimate that an average of 8,224 enteric infections are reported as contributing causes of death in the United States each year. The National Vital Statistics Report for 1997 listed 5,086 deaths due to shigellosis, amebiasis, other intes- 64 Peterson and Calderon tinal infections, and viral hepatitis along with 6,820 deaths due to “all other infectious and parasitic diseases” not including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (15). Because the National Vital Statistics Report includes nonenteric infectious diseases (e.g., pneumonia and influenza) in the same category as the enteric pathogens we examined, its reported numbers are higher. The steady increase in reports of viral enteric disease as a cause of death in the MCD data could be due to several factors: 1) over time, physicians may be coding more contributing causes of death; 2) the US population is aging, and increasing numbers of aged and immunocompromised Americans are susceptible to viral enteric diseases; and 3) techniques for diagnosing specific enteric viruses have improved since 1989, so it is more likely that decedents could have been diagnosed with viral enteric infections before death and the code was then included as a contributing cause of death. The difference in the rate of increase for viral as opposed to bacterial pathogens supports the hypothesis of changing diagnostic techniques that allow for more detection of viral infections. An analysis of the number of causes of death coded for each record during the years under study indicated that the mean number of causes of death coded was 3.11 per decedent, with a variance between years of 0.0008. This indicates that the number of codes recorded for each decedent was nearly constant over time, and the increased number of reports of enteric disease related to death was not due to a change in the usual number of causes of death coded for each decedent. Analysis of the underlying cause of death separate from all contributing causes combined revealed that the rate of viral enteric diseases’ being reported as the underlying cause of death more than doubled during the study period (from 0.48 deaths per 100,000 population in 1989 to 1.20 deaths per 100,000 population in 1996). The rate of reporting of any enteric disease as the underlying cause of death is also increasing and is being driven by the increased reports of viral enteric deaths. Rates of reporting of bacterial and other microbial enteric infections as the underlying cause of death approximately doubled over the study period (bacterial infections: from 0.12 deaths per 100,000 population in 1989 to 0.21 deaths per 100,000 population in 1996; other microbial infections: from 0.11 deaths per 100,000 population in 1989 to 0.21 deaths per 100,000 population in 1996). Bacterial and other enteric microbial deaths represent a small fraction of the deaths related to viral enteric infections. Determining the true cause behind observed differences in enteric disease burden within population groups or for specific pathogens is beyond the scope of this analysis. hood morbidity and mortality from 1948–1986 estimated that 325–425 US children under 5 years of age die from diarrhea each year (16). Since different International Classification of Diseases codes were used, our death estimates cannot be directly compared with those of other studies, but our estimates were similar in magnitude to those of the previous review. Black children under 5 years of age have enteric infections listed as a cause of death more than four times as often as children of other races in the same age group. This suggests that factors other than pathogen virulence are responsible for the greater risk of mortality associated with these infections in some children. Black decedents less than 5 years old had ICD-9 codes for disorders relating to short gestation and low birth weight (ICD-9 codes 765.0 and 765.1) included on their death certificates twice as often as decedents from the White and Other racial categories (Black, 19.5 percent; White, 8.8 percent; Other, 10.9 percent). Other factors and exposures not captured on the death certificate may also contribute to increased risk of death from enteric disease. Enteric disease burden in children Impact of enteric disease Generally, children have high rates of viral infection because they have not yet acquired immunity to viral pathogens. The low reporting rates for viral disease associated with children’s deaths, however, suggest that while children may experience higher rates of enteric viral infection, these infections are rarely so serious as to cause or contribute to death. We estimated that enteric diseases are reported as a contributing cause of death for 456 children under age 5 each year. A review of studies of the impact of diarrhea on child- In 1996, 0.37 percent of deaths were related to enteric disease (8,589 deaths out of 2,318,212). This is 2.6 times the 1989 value of 0.14 percent. The average percentage increase from one year to the next in the fraction of deaths related to enteric disease from 1989 to 1996 was 116 percent (range, 111–122 percent). As the population ages and as more Americans live with compromised immune systems, the fraction of deaths related to enteric disease will continue to increase. Enteric disease in the immunocompromised The immune status of persons infected with HIV makes them more susceptible to enteric infections and more likely to be suffering from a serious enteric infection at the time of their death. The most interesting trend possibly affecting this subpopulation is the increasing rate of reported viral enteric disease associated with death among people aged 25–45 years (figure 2). The rate was fairly linear in 1989, but by 1996 there was a distinct rise in the rates of reported viral enteric disease associated with death. It is possible that this is a direct result of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic in those age groups. Peak mortality associated with AIDS occurs among persons aged 30–34 years (17). The rates of reported death associated with protozoal enteric diseases increased similarly in both Blacks and Whites, centered at the 35- to 44-year age group. This finding agrees with current prevalence figures for HIV and AIDS indicating that the age category with both the highest incidence of AIDS and the highest mortality from AIDS is 30–34 years in all racial/ethnic groups (17). A similar increase in the rate of reported other enteric microbial infections associated with death is slightly evident among Blacks. This increase may also be due to HIV infection, because the prevalence of HIV infection is higher among minority Americans than in the White population (17). Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 Enteric Disease as a Cause of Death 65 Deaths related to bacterial enteric disease in the elderly, a quickly growing segment of the US population, are increasing at a greater rate than in any other age category. This also suggests that enteric disease will be a continuing and expanding burden on the health care system unless better prevention and control measures are found and implemented. The fact that hepatitis A, a vaccine-preventable disease, is contributing to the deaths of more people each year should not go unnoticed. Vaccination against hepatitis A may be one public health intervention strategy for reducing preventable deaths. Another factor affecting the number of deaths related to enteric disease each year is the number of Americans living with HIV infection (ICD-9 code 042). Of the deaths related to enteric disease in 1989, 3.3 percent also included HIV as a cause of death (161 deaths out of 4,912); by 1996, this fraction had increased to 4.6 percent (592 deaths out of 12,906). In summary, the rate of reporting of enteric diseases as contributing causes of death more than doubled between 1989 and 1996. People over age 65 years have the highest rates of reporting of enteric diseases as causes of death. Viral enteric diseases contributed to an increasing number of deaths among people in the 35- to 55-year age groups during the study period, probably because of the impact of HIV and AIDS in that population. Nonwhite Americans are most affected by enteric diseases as contributing causes of death. While enteric disease caused many fewer deaths in the 1990s than in the 1920s, these diseases remain an important and often preventable contributor to mortality in the United States. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Funding for this analysis was provided by a Biostatistics for Research in Environmental Health training grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and by an NHEERL-DESE Cooperative Training Agreement in Environmental Sciences Research (EPA CT826513) from the Environmental Protection Agency. REFERENCES 1. Franco EL. Defining safe drinking water. (Editorial). Epidemiology 1997;8:607–9. 2. Garthright WE, Archer DL, Kvenberg JE. Estimates of incidence and costs of intestinal infectious diseases in the United States. Public Health Rep 1988;103:107–15. 3. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of foodborne illnesses—selected sites, United States 2001. MMWR Morb Mor- Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:58–65 tal Wkly Rep 2002;51:325–9. 4. Wright RO. Life and death in the United States: statistics on life expectancies, diseases and death rates for the twentieth century. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc. 1996. 5. Bureau of the Census, US Department of Commerce. Historical statistics of the United States: colonial times to 1970. Bicentennial edition, part 1. Washington, DC: US GPO, 1976. 6. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1996. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 2702). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1999. 7. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1995. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 2392). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics 1998. 8. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1994. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 2201). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1997. 9. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1993. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 6799). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1995. 10. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1992. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 6546). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1994. 11. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1991. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 6320). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1993. 12. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1990. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 6319). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1993. 13. National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple cause of death, 1989. (Computer file). (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research study no. 6257). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1992. 14. Bureau of the Census, Population Division, Population Estimates Program. US population estimates by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1980 to 1998. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, US Department of Commerce, 2000. (World Wide Web URL: http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/ nation/natdoc_rl.txt). 15. Hoyert DL, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 1997. Natl Vital Stat Rep 1999;47:1–104. 16. Glass RI, Lew JF, Gangarosa RE, et al. Estimates of morbidity and mortality rates for diarrheal diseases in American children. J Pediatr 1991;118:S27–33. 17. National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through June 1999. (HIV/AIDS surveillance report, vol 11, no. 1). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999.