* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

Survey

Document related concepts

Reforestation wikipedia , lookup

Introduced species wikipedia , lookup

Ecology of Banksia wikipedia , lookup

Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

Island restoration wikipedia , lookup

Conservation movement wikipedia , lookup

Conservation psychology wikipedia , lookup

Conservation biology wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity wikipedia , lookup

Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project wikipedia , lookup

Operation Wallacea wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Robert Boden

Consultant to

Science, Technology, Environment and Resources Group

29 May 1995

Parliamentary

Research Service

Research Paper No, 261994/95

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

AjiJlllist ofcurrent Parliamentary Research Service publications is available on

the ISR database

A quarterly update ofPRS publications may be obtainedfrom the

PRS Head's Office

Telephone: (06) 277 7/66

CONTENTS

Major Issues

_

1

_

Introduction

3

What is it about Australia's environment which encourages biodiversity?

3

Isolation

Size

Rainfall

Soils

Fire

Summary

3

4

4

4

4

5

:

Australian biodiversity

Species diversity

Vegetation and habitat diversity

5

5

6

"

9

Importance of biodiversity

9

New uses for plant biodivenity

Phannaceutical products

10

10

10

Cutflowers

Forest tree seed

Land use and vegetation change

Past and present land use patterns

Vegetation change

11

Threats to divenity

17

17

18

11

12

Species lost and under threat

Loss of habitat.

Feral animals and weeds

Erosion and soi Idegradation

Fire

Dieback disease

lIIegal trapping

Conserving biodiversity

"

"

20

21

21

21

22

22

Plant communities

22

Research and survey

23

International conservation agreements

Parks and reserves system

24

24

Other public lands

Private and leasehold land

25

26

References

29

Appendix

32

TABLES

1.

Proportions of endemics at the species level for each major species group

2.

Forest cover in world regions

12

3.

Decline in forest cover 1788-1980 for each Australian State and

mainland Territory

13

Decline in woodland cover 1788-1980 for each Australian State and mainland

Territory

14

5.

Changes in vegetative cover between 1788 and 1980

17

6.

Numbers of endangered. vulnerable and presumed extinct species in Schedule 1

ofthe Endangered Species Protection Act /992 (at 30 April 1993)

17

4.

6

FIGURES

I.

Major vegetation types in Australia

7

2.

Distribution of threatened (endangered and vulnerable plant species)

16

3.

The distribution of the koala

19

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

I

Major Issues

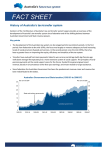

The tenn biodiversity, or biological diversity, has recently emerged from the scientific literature

into everyday language. The reason for this lies in an awakening to the fundamental importance

of biodiversity to Australia's wellbeing and the recognition of increasing threats to it.

Plants and animals and their environments are major factors in attracting international tourists

with over 75 per cent identifying natural scenery and wildlife as key elements in their decision to

come to Australia. In addition, it has been estimated that at least 10 million Australians visit

natural environments each year and over four million visit major zoological gardens. A

household survey carried out by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 1993-94 revealed that 42.3

per cent of the Australian population over the age of 18 years visited at least one botanic gardens

in the previous year.

This paper describes the geographical characteristics which have resulted in Australia being

recognised as one of about a dozen world centres of megadiversity which, together, account for

60-70 per cent of the world's biodiversity. The extent of Australia's biodiversity is described in

tenns of species and habitats and its economic and cultural importance.

The major changes to biodiversity which have occurred since European settlement and are still

occurring, are identified. By far the most significant change is the continued clearing of native

vegetation with the subsequent loss of species of plants and animals and their habitats.

Compared to other major inhabited countries Australia is the least forested, making vegetation

management one of the most important resource management issues. In about 200 years,

approximately 50 per cent of the forest and 35 per cent of the woodland has been cleared. The

annual rate of clearing is still between 500 000 and 600 000 hectares; an area equivalent to about

five and a half million 'quarter acre' house blocks. Most clearing is occurring in Queensland and

NSW: 450 000 ha and ISO 000 ha respectively in 1990. Areas cleared in Victoria, Tasmania and

South Australia were much less: 6 156 ha, 5 999 ha and 4 4 71 ha respectively.

Since European settlement, 115 species of plants and animals have become extinct and about

300 are classified as endangered and therefore at risk of extinction in the short tenn unless the

existing threats to them are removed or drastically reduced. Leigh and Briggs (1992)

identified grazing and agriculture. mostly following clearing, as responsible for well over 90

per cent of plant extinctions and by far the major present and future threat to plant species

classified as endangered nationally.

Feral animals and weeds have had major impacts on the Australian natural environment. Rabbits,

pigs and faxes are three of more than seventy species of animals which have been introduced and

become established in the wild since European settlement began. At least 2 000 species of

introduced plants are now a pennanent part of the landscape; it is estimated that the total cost of

weeds to the Australian economy is $4 000 million annually.

Road and rail easements are significant areas of public land. In Victoria, for example, roads

occupy about 2.5 per cent of the State. In 1987 there were 870 OOOkm of roads in Australia.

While a large part of the road reserve is dedicated to its primary purpose of carrying traffic, in

rural areas there are often extensive verges which are important habitat for plants and some

Australian Biodiversity Under Throot

Z

animals. The significance of road easements for biodiversity conservation has been recognised

by the Australian Road Research Board which has prepared a draft National Strategy for

Roadside Reserve Management.

There is no doubt that the survival of animals is linked with that of vegetation. But while the

work of Dr Harry Frith and others who followed him clearly indicates that vegetation types have

fonned the most practical basis for detennining conservation reserves in the past, it is unwise to

assume that protecting examples of all of them will necessarily ensure that the diversity of

animals is also adequately conserved.

The major effort to protect biodiversity lies within the parks and reserves system which now

occupies about 6.4 per cent of the country. This system does not adequately cover the range of

habitats, however, and it is becoming increasingly clear that private land and land managed by

other public agencies must playa larger role in conserving Australian biodiversity.

Two ways of achieving this would be stronger controls on clearing remnant native vegetation on

both public and private land and greater incentives for private landowners and leaseholders to

become involved in nature conservation. Justification for public funding of such incentives lies in

recognising that it is the increasing number of urban dwellers which is driving the increasing

demand for food, fibre, water and recreation, most of which comes from rural land. It also lies in

the concept of intergenerational equity, bener known in the Australian ethos as 'wanting to look

after the kids'.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

J

Introduction

Biodiversity. greenhouse effect and the southern oscillation index are environmental terms

which now appear daily in the media and are part of the curricula in schools and colleges

around the country.

Biodiversity, or biological diversity as it is sometimes called, is the variety of life on which

the health of our environment depends. It comprises all living plants. animals including

humans, micro-organisms and their habitats. It is the source of foods, fibres, medicines,

building materials and recreational opportunities. Expressed in landscapes and seascapes it

provides inspiration for art, culture and reflection on the meaning of life.

According to the draft National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia (1994),

biodiversity is considered at three levels:

• genetic diversity - the variety of genetic information contained in all of the individual

plants, animals and microorganisms that inhabit the earth. Genetic diversity occurs

within and between the population of organisms that comprise individual species as well

as among species;

• species diversity - the variety of species on the Earth;

• ecosystem diversity • the variety of habitats, biotic communities and ecological

processes.

This paper aims to explain why Australian biodiversity is different and special and why it

is important to conserve it. Clearly, society's demands put pressure on biodiversity. Some

of these threats, how they are being handled now, and how they might be handled better,

are discussed in the paper.

Australians are sometimes apt to blame the inadequate knowledge of the past for the

present state of the environment. We now have much of the knowledge to do better, but do

we have the will to ensure that future generations can be grateful?

What is it about Australia's environment which

encourages biodiversity?

The case for conservation of Australian plants and animals and their habitats is often based on

the argument that Australia is very different from the rest of the world, particularly the

northern hemisphere where the vast majority of people live. But, is this really true and, if so,

why?

Isolation

Australia was originally part of a huge land mass called Gondwanaland consisting of what

is now Antarctica, South America, Africa, India and New Zealand. It broke free about 40

million years ago and began drifting slowly northwards, isolated from other lands by deep

oceans which only a few birds and marine mammals could cross. About ten million years

ago the Australian tectonic plate made contact with that of Asia enabling some invasion

from the north by plants and animals. The first human settlers arrived between 40 000 and

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

if

60 000 years ago bringing some new species with them. However it is only in the last 200

years that major introductions of new plants and animals have occurred.

This history means the great majority of native plants and animals have evolved m

isolation and are therefore very different from those in other parts of the world.

Size

The large size of the country, about 7.68 million square kIn or 5.7 per cent of the land surface

of the earth, is also important. It is nearly 25 times the area of Great Britain and Ireland and

about equivalent to the United States of America, excluding Alaska. It spans 4 000 kIn east

to west and about 3 700 kIn north to south with 39 percent in the tropics and 61 percent in the

temperate zone.

Rainfall

Australia's geographic position in relation to large ocean masses results in an intensive

atmospheric circulation pattern. Rainfall is not only low but unreliable over much of the

country. varying widely from year to year. Droughts and floods occur so frequently in many

areas they are considered part of the 'normal' climatic pattern. In these areas successful plants

and animals are those adapted to withstand both very wet and very dry periods as well as

average conditions.

The average annual rainfall is only 42 mm compared to 86 rnm for the world's land surfaces

as a whole. This means there are few large rivers and the largest, the Murray River system,

has a very small average run-off. By contrast. run-off from the Mississippi is 40 times, the

Congo 118 times and the Amazon is 148 times greater than the Murray.

Soils

There has been no significant mountain building in the last 100 million years and no recent

volcanic activity (both of which result in new soil formation). Australian soils are therefore

very old. Even though annual rainfall has been low, the long period over which it has acted

on the soils has resulted in severe leaching of nutrients so that naturally occurring nitrates and

phosphates are about half those of some overseas soils.

Prairie soils which enable crops to be grown throughout vast areas of the United States and

Canada are poorly represented in Australia. Generally low phosphorus levels mean that many

native plant species have become so well-adapted to this condition they will not thrive in

phosphate-enriched soils in cultivation. Naturally saline soils are common due to ineffectual

continental drainage.

Fire

Fire was part of the natural environment long before humans arrived and many native plants

developed adaptions related to periodic burning. The natural fire pattern was changed by

Aboriginal people who developed 'fire stick fanning' to drive game out into the open when

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

5

hunting, to clear paths through the rainforest and to regenerate plant food for themselves and

the animals they used.

It has been demonstrated convincingly that the sedgeland of the west coast of Tasmania is the

result of long use of fire which gradually changed the original rainforest, dominated by the

fire-sensitive beech, Nothofagus cunninghamii, through a phase of mixed eucalypts and

rainforest to scrub and finally heath and sedgeland. With cessation of Aboriginal burning,

rainforest is invading its former habitat in some places.

Different fir~ regimes were used in different parts of the continent. In Amhem Land fire

management was designed to spare fire-sensitive jungle thickets which contain many edible

plants that do not readily regenerate after burning. Wide firebreaks were burnt around these

areas early after the wet season so that later burning in the dry period would not enter the

protected areas.

Aborigines had no capacity or incentive to put fires out and camp fires were left to smoulder

and hunting fires to bum themselves out. Regular burning of tribal territory every three or

four years prevented the accumulation oflitter and disastrous wildfires.

The fire pattern changed again with European settlement. Frequent light burning gave way to

attempts to prevent fire which inevitably led to large accumulations of fuel and devastating

fires. Contemporary Australians are still trying to come to terms with the 'red steer'.

Summary

This combination of long isolation, large size, rainfall, soils and fire prevalence has produced

an array of plants and animals which are different from those in the rest of the world; so

different in fact that considered together over 80 per cent of Australian plants and animals

occur only in this country.

Not only are Australia's plants and animals different from those in the rest of the world but

they are very different from each other. It is these differences which make up biodiversity.

Australian biodiversity

Species diversity

Some idea of biodiversity on a world basis can be gained when it is recognised that there are

more than 9 000 species of birds, 6 300 species of reptiles, 4 000 species of mammals, 4 000

species of amphibians, 21 000 species of fish, 275 000 species of plants and over 1 million

invertebrates and micro-organisms (Australian Academy of Science, 1994).

Some parts of the world are richer than others in numbers of species of plants and animals.

Australia is accepted internationally as one of about a dozen megadiversity countries which

between them account for 60-70 per cent of the world's biodiversity (DASET. 1991).

AuslraJian Biodwersily Under Threat

6

Australia has the planet's second highest number of reptile species (750), is fifth in flowering

plants (22 000), and tenth in amphibians (200) (House of Representatives Standing

Committee on Environment, Recreation and the Arts, 1992).

lbe richness of biodiversity is reflected in the fact that there are more species of ants

inhabiting Black Mountain in Canberra than in the whole of Britain. Furthennore, only

I 600 vascular plants are found in Britain compared to the much smaller area around Sydney

which has over 2000 species (Flannery, 1994).

As indicated above, a distinctive feature of Australia's plants and animals is that many species

are endemic, that is, they are found naturally only in Australia. The proportions of endemics

at the species level for each major group are presented in Table 1 and range from 45 per cent

for birds to almost 100 per cent for insects.

Table J

Proportions of endemics at the species level

for each major species group.

Species Group

Birds

Reptiles

Mammals

Amphibians

Invertebrates

Number of Australian

Species

777

750

282

200

est. 225 000

Flowering Plants

22000

Proportion of endemic

species oAt

45

89

82

93

generally high approaching

100 for some groups

85

Source. Dept. ofthe Environment, Sport and TerritorIes, J994

Vegetation and habitat diversity

In its simplest expression there are seven major land vegetation or habitat types in Australia

although within each there is a myriad of different associations, each with its individual

complement of plants and animals. The major vegetation types are open and closed forest,

woodland, shrubland, scrub (mostly mal lee), heath and herbland or grassland (Figure J)

Although the boundaries between vegetation types are sharp on maps, in reality they are often

gradual and fluctuate over time. For example, the boundary between woodland and open

forest and woodland and grassland may often be hard to detect and certainly the more mobile

animals move freely from one to the other. Birds in particular may rest and nest in the forest

but feed in the open grassland most of the time.

Vegetation types are classified according to height, fonn and density of crown cover

projected onto the ground leading to terms like closed or tall forest, open forest, woodland

and grassy woodland. Within the major vegetation types, descriptive terms indicating the

most obvious species are used. For example, river red gwn forest, yellow box woodland,

brigalow scrub and kangaroo grassland are common terms.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

.

.'

0-" m

3 ~

a <

~. ~

~

~i

~. i

i

,

0

I

C"

•

~

~.

~o

I

Ul

~

C

2-

0.

~

3: .;;, >-~

." p. n

iD~ ,

m" •

,

-~

•,

a •

0

~

~

3

:e. ;;;

<

0. . iOQ.

III :;:0

.

"

'"

""

"" "" . -.

C"

0"0

Q

o ..

'1: c."

0

~

0

~

C

0

0. 0.

~

~

~

0.

~

~

~

•

"~

~

1l

.

!i.

Figure 1: Major Vegetation Types in Australia

Source:

Leigh, J., Boden, R and Briggs. J (198-1) £r/ine' and Endangered Planls of

Australia, Macmillam Australia.

7

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

8

It is rather more difficult to describe animal habitats in tenns of the species within them. This

is due in part to the fact that botanists have produced vegetation classifications to meet their

own purposes which do not necessarily have much to do with the distribution of vertebrate

fauna. For example, botanists attach less significance than zoologists to habitat features such

as dead or decaying trees with holes or hollows essential for some animals.

There are also many difficulties with the animals themselves. The distribution of amphibians

and reptiles seems to be controlled largely by micro-environment rather than by broad

vegetation associations. Soil hardness, ground vegetation, amount of shade and other factors

may be more important to some small manunals than vegetation structure at a level which can

be seen and mapped.

Migratory species may live in different habitats at different times of the year; for example. it

is estimated that 44 per cent of the 260 species of birds found near Canberra spend part of the

year elsewhere. An example is the pink robin, Petroica rodinogasler, which lives in

rainforest in Tasmania in summer and woodland on the mainland in winter. This pattern

again emphasises the importance of habitat conservation at both ends of migratory paths, and

often in between, for some species to survive. On an international scale this concept forms

the basis for agreements between Australia and some other countries such as China and Japan

for the protection of birds which migrate between them. There are at least 55 species of

wading birds in Australia, 35 of which are regular migrants from Asia. It would be sadly

ironic for the Japanese goverrunent to protect the grasslands where the Japanese snipe.

Gallinago hardwickii, breeds if, when it migrates to Australia in summer. the estuaries and

mud flats it needs have been converted to destination resorts for tourists, many of them also

from Japan.

Where forest, woodland. scrub and grassland tend to merge into one another it is difficult to

assign an animal to one particular vegetation type. Also some species are 'fringe dwellers'

inhabiting the interface between one plant community and another and are favoured by a

mosaic of different types.

Despite these difficulties the late Dr Harry Frith in his· pioneering work Wildlife Conservation

(published in 1973) was able to determine the approximate distribution of most species of

birds and mammals among the different vegetation associations Australia wide. Woodland

was found to support more species than any other vegetation type.

Among the birds 323 species (48 per cent) are able to live in woodlands and to 227 species (34 per cent)

it is the most important habitat; 20 per cent of the bird species are practically confined to it. Among the

mammals the percentages are higher; excluding the bats, 135 species (76 per cent) live in woodlands and

to 227 species (34 per cent) it is the most important habitat; 20 per cent of the bird species are practically

confined to it. Among the mammals the percentages an: higher, excluding the bats, 135 species (76 per

cent) live in woodlands. It is the main habitat of 30 per cent of the mammal species and the great

majority of these live nowhere else (Frith, 1973).

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

9

There is no doubt that the survival of animals is linked with that of vegetation. But while the

work of Dr Harry Frith and others who followed him clearly indicates that vegetation types

have fonned the most practical basis for detennining conservation reserves in the past, it is

unwise to assume that protecting examples of all of them will necessarily ensure that the

diversity of animals is also adequately conserved.

Importance of biodiversity

Biodiversity provides variety in human food and is the source of many medicines and

industrial products. It is also important in enriching human cultural life and stimulating

artistic endeavour. One of the great deprivations identified by people who have been

confined as hostages for long periods is the absence of other living things around them; the

sound of birds, the scent of flowers.

Plants and animals and their environments are major factors in attracting international tourists

with over 75 per cent identifying natural scenery and wildlife as key elements in their

decision to come to Australia. In addition, it has been estimated that at least 10 million

Australians visit natural environments each year and over four million visit major zoological

gardens (DEST, 1993). A household survey carried out by the Australian Bureau of Statistics

in 1993-94 revealed that 42.3 per cent of the Australian population over 18 years of age

visited at least one botanic gardens in the previous year (Fagg and Wilson, 1994).

Biodiversity is economically important in protecting water catchments from extreme events

such as floods and droughts. A Victorian Government sponsored study calculated the

financial benefit of water supplied to Melbourne from forested catchments at $250m per year

(Read, Sturgess and Associates, 1982). Not only is the yield from vegetated catchments more

consistent than from cleared catchments but the filtering process through leaf litter results in

water of high quality.

The top few centimetres of soil are fundamental to continued productivity of the land.

Diverse soil microorganisms living there are essential for litter breakdown and nutrient

recycling while plant roots in the zone prevent erosion and soil loss. Biodiversity in

microorganisms is also essential in the breakdown and absorption of many pollutants and

wastes created by humans.

New uses for plant biodiversity

The importance of native timbers in the Australian economy began with the export of the first

red cedar, commonly known as 'red. gold', from Sydney within seven years of settlement.

Although cedar logging had virtually ceased by the beginning of this century due to

overexploitation, eucalypt woodchips remain important, if somewhat contentious, export

products.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

10

Pharmaceutical products

An example of a less contentious use of a native plant product is the discovery of the

chemical compound conocurvone in a Western Australian smokebush belonging to the genus

Conospermum. Conocurvone has shown promise as a treatment for AIDS.

Following the discovery of conocurvone, the Western Australian Department of Conservation

and Land Management established three vital principles to be followed in further

development. These are:

• that the species be protected;

• that Australian science be involved directly in developing the compowld; and

• that in the event a drug is developed, then the community of Western Australia should gain

an equitable share of the profits (Letter from Acting Executive Director CALM to the

Editor, The Bulletin 7/1/93).

A research consortium of government and university scientists was established to develop

conocurvone to a marketable product. In addition to the phannaceutical aspects, research

involves determining methods of vegetative propagation and limits on wild harvesting of

smokebush.

The cost of developing a natural plant product into a marketable drug is enormous and the

Western Australian Government has joined with an Australian company to carry out further

research. It has been estimated that if the early promise shown by concurvone is realised and

it becomes a successful drug the State could receive royalties by the year 2002 of $100

million a year (Armstrong and Hooper, 1994).

Cutflowers

Export of native wildflowers and plants is an expanding industry which has grown from $2m

in 1981 to $22m in 1993. Almost two-thirds are fresh flowers from Western Australia but

dried flowers and foliage are also important and other states are now participating. The top

customer countries are Japan, USA, Germany and the Netherlands (RIRDC, 1994).

The domestic market for cut flowers is estimated to have a present retail value of S250-350m

but at this stage only 5-8 per cent of the market is native flowers with exotics like roses,

carnations and daffodils being more popular. This is clearly an area where national taste

could be changed.

Forest tree seed

Apart from limited alpine areas above the treeline, rainforest, extreme desert and some

treeless grassland, the Australian landscape is distinguished by gum trees and wattles. There

are more than 500 species of eucalypts, 800 species of acacia and I 200 tree species of

rainforest origin. Over 90 per cent of these species are found only in Australia.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

1J

About 200 tree species are commercially significant in Australia and overseas at this stage

and there is considerable interest in the potential of others for both their wood and

pharmaceutical products.

About 25~30 tonnes of tree seed worth S9m are exported annually to over 130 countries to

establish plantations for timber, firewood, amenity and erosion control. Export of this

amount of seed raises a dilemma in relation to access to Australia's unique forest genetic

resources (Fryer, 1994). On the one hand, it may be argued that Australia has relied heavily

on imported genetic resources for its agricultural industries and should reciprocate with forest

genetic resources. On the other hand the Convention on Biological Diversity encourages

countries to conserve genetic resources and to seek an appropriate share of the benefits. A

balance between 'free' exchange for research and development for commercial purposes needs

to be achieved. Fryer (1994) recommended that State and Commonwealth forestry agencies

develop policies which would meet commitments under international agreements while

protecting sovereignty over biological resources.

Land use and vegetation cbange

Past and present land use patterns

Australian land use has progressed through three major phases. The first ~as the Aboriginal

phase of hunting and gathering which lasted for more than 40 000 years. The second phase

covered just over a hundred years of European colonisation from 1788 to early this century.

It involved pioneering agriculture, grazing and timber harvesting. Mining was intensive

where it occurred but occupied only a relatively small part of the country.

The third phase from the early 1900s has seen consolidation of the pioneering efforts,

intensification of land use and large increases in land productivity where new scientific or

technical discoveries could be applied.

About 64 per cent of the country is allocated to agriculture and grazing. However, only 4 per

cent of this area is cropped and 6 per cent is sown pasture. The remaining 90 per cent is

modified or unmodified native vegetation some of which is vulnerable to clearing.

There has been an increase in the area allocated to mining as open-eut methods have been

developed for extraction of coal and iron ore. Beach sands have been mined for rutile and

zircon. Urban expansion, often onto agricultural land, and alienation of coastal and estuarine

areas for industrial, recreational and tourist activities have occurred. Even so, only about 0.6

per cent of the country is used for urban development, transport routes and mining although it

must be recognised that these activities have influences well beyond the area where they

occur. For example, urbanisation requires raw materials such as sand and gravel during the

construction phase and once established, draws on other land for water, food and recreation.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

In a discussion of vegetation clearance controls

emphasised that

In

12

South Australia, Bradsen (1994)

modem agriculture only exists because of the demands of cities which in tum can exist

only because of modem agriculture...it must be acknowledged that the whole community

has a responsibility, and a legitimate interest in, the sustainability of both agriculture and

biodiversity.

Australia has about 417 000 sq km of native forests but the area available for logging is only

about 134 000 sq k.m after inaccessible areas, roads, streambanks and other reserves are

excluded. There are 8 918 sq Ian of softwood and 846 sq Ian of hardwood plantations (RAe,

1991).

Land fonnally dedicated to nature conservation has increased to 403 867 sq km or about 6.4

per cent of the total land surface (Hooy and Shaugnessy, 1991). Aboriginal land occupies

about 12 per cent while the remainder is either unused or put to other undefined uses.

Vegetation change

Compared to other major inhabited regions of the world. Australia is the least forested,

making vegetation management one of the most important resource management issues

(Table 2).

Table 2

Forest cover in world regions

Geographic Region

Forest area 'OOOsq km

7916

Former USSR

7393

South America

4593

North America

3619

Asia (excluding USSR)

Africa

2359

1370

Europe

417

Australia

World Total 27667

Forest area as

percentage of total

land area

36

37

25

14

8

29

5

23

Source. AustralIan Academy a/ScIence, /994

An inquiry into the use of Australian forests and timber by the Resource Assessment

Commission (1991) found that about 50 per cent of forest had been cleared or severely

modified since European settlement. Calculations made by Wells, Wood and Laut

reproduced in the State of the Environment Source Book published in 1986 (Table 3) also

indicate about 50 per cent loss of forests.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

IJ

Table 3

Decline in forest cover 1788-1980

for each Australian State and mainland Territory

State or Territory

% with forest

cover 1788

NSW

Vic

Qld

WA

SA

Tas

NT

ACT

Australia

20

38

21

I

0.2

47

4

59

9

0/0 with forest

cover 1980

6

13

11

0.4

0.07

25

3

26

4.5

0.10 of original

forest cover lost

70

66

47

60

66

47

25

56

50

Source. State ofthe Environment In Australia. Source Book., AGPS /986

While loss of woodland has not been as great, it still amounts to about 35 per cent (Table 4).

There are more endangered and vulnerable plant species in some parts of the country than in

others. Figure 2 (see page 16) taken from Briggs and Leigh (1995 in press) shows the

number of threatened (endangered and vulnerable) plant species in each of 80 botanical

regions across Australia. Generally the high numbers occur along the eastern seaboard and in

the south-west of Western Australia where the greatest amount of clearing has taken place.

The high number in Cape York results from both clearing and overcolJecting of orchids and

ferns.

Examination of the figures presented in Tables 3 and 4 reveals that the percentage of forest

and woodland lost varies markedly from state to state with the south-eastern states, where the

majority of Australians live, suffering most. Even within individual states there is

considerable variation in intensity of clearing. In some cases this is related to the type of

native vegetation and new technology. For example. 'the development of new clearing

techniques has allowed the almost complete destruction of the brigalow and now, the poplar

box woodlands' (in Queensland) (Kirkpatrick, 1994).

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

14

Table 4

Decline in woodland cover 1788-1980

for each Australian State and mainland Territory

State or Territory

NSW

Vic

Qld

WA

SA

Tas

NT

ACT

Australia

woodland

cover in 1788

0/0

57

34

28

14

6

31

22

38

23

0/0

31

8

20

9

3

20

22

13

15

woodland cover

in 1980

of original

woodland cover

lost

46

76

28

36

50

35

0/0

66

35

Source. State o/the EnVIronment In Australta. Source Book. AGPS 1986

The mean annual deforestation rate for forest and woodland from 1788-1985 has been

estimated at 359 OOOha or 0.09 per cent per annum (AUSLIG, 1990) (Forest and woodland

were defined as natural vegetation dominated by trees. excluding mallee and mangroves).

Estimates compiled recently for the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory reveal that the

annual rate of clearing forest and woodland, largely for agriculture, between 1983-93 was

568 OOOha, far exceeding the average annual rate for the past 200 years. Even more alarming

are the annual figures for the latter part of this decade. In 1988,719 OOOha were cleared and

in 1990 the figure still reached 665 OOOha (NGG1 Committee, 1994).

These figures were obtained from a range of sources within each state and territory.

However, the Inventory includes the qualification that '...these figures are very preliminary

estimates which we have no way of verifying until land clearing rates can be developed using

remotely sensed data'. Even with this qualification, however, the present rate of clearing far

outstrips the capacity of any programmes to 'regreen' the country. For example, the One

Billion Tree program is likely to replant at best 50 OOOha per year. While it is significant in

addressing the most denuded areas and is supported by other Landcare programs such as Save

the Bush, the gap between treed and untreed land can only widen dramatically each year if

present clearing rates are allowed to continue.

Clearance is usually expressed in hectares while planting is expressed in numbers of trees.

This obscures the reality that some areas of malIee have a tree density before clearing of

I 000 trees per hectare. 'In blue gum woodland and stringy bark woodland numbers of

significant or mature trees are estimated to range between 50-100 and 100-900 trees per

hectare respectively' (Bradsen, 1995). Where understorey plants are concerned, the figures

are far higher. For example, counts of up to 7 900 broom bush per hectare have been

recorded where it is relatively pure and 5 200 as a combined understorey on Kangaroo Island

(Bradsen, 1995).

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

/5

It must also be recognised that clearing removes not only the trees but the shrubs. grasses and

other small plants which comprise the whole plant community. When the plants are lost so

are the animals including the insects and often the soil fauna which depend upon them.

Most clearing is occurring in Queensland and NSW; 450 OOOha and 150 OOOha respectively in

1990. Areas cleared in Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia were much less: 6 156ha,

5 999ha and 4 471 ha respectively.

The dynamics of vegetation change are reflected in results published by AUSLlG, 1990, and

presented in simplified form in Table 5 taken from the Australian Academy of Science

textbook for senior school students Environmental Science.

The biggest change in the type of vegetation cover between 1788 and 1980 has been the

increase of 130 per cent in the area of grasslands and pastures at the expense of the forest,

woodland and shrubland.

Grassland in southern Australia, however. is now dominated by exotic grass species. The

sweeping expanses of native grasses which excited early explorers like Major Mitchell have

been lost. It is estimated that a staggering 99.5 per cent of native grasslands in Victoria have

been destroyed in only 150 year.; (Scarlett et aI, 1992). Not only have the native grasslands

species gone but also the animals that lived there.

This loss of grassland species is exemplified in a record by pioneering journalist John Gale

published in 1927. While walking through what is now the centre of Canberra, John Gale

came across a flock of plain turkeys (bustards) 'scores in number' which 'continued feeding.

merely parting to permit my passing though the flock' (Gale, 1927).

The only turkeys to be found now in Canberra are domesticated ones in supermarket freezers!

A massive reduction in the rate of clearing native vegetation accompanied by replanting

native species of trees, shrubs and grasses is essential if further loss of plant and animal

species is to be avoided. Existing remnants of native vegetation must be protected and

encouraged to expand to fonn first corridors and then broad superhighways linking national

parks and nature reserves.

.-

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

•

•

.

...

Figure 2: Distribution of threatened (endangered and vulnerable)

plant species.

Source: Briggs, 10 and Leigh, JH (1995), Rare or ThreaJened Australian Plants, 1995 Revised

Ed. CSIRO Melbourne (in press).

16

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

/7

Table 5

Changes in vegetative cover between 1788 and 1980

(thousand sq km)

1788

Vegetation

1980

690

1 570

1650

1610

1470

500

Forest

Woodland

Open woodland

Shrubland

Open shrubland

Grassland and

pasture

Changes in cover

%

390

1070

2000

860

2020

1 150

-43

-32

+21

-47

+37

+130

Source. EnVIronmental &tence, AustralIan Academy a/Science, /994

Tbreats to diversity

Species lost and under threat

Since European settlement began, about 74 species of flowering plants and 41 species of

birds and mammals have become extinct. Many others are threatened with extinction unless

actions are taken to remove or relieve the threatening processes.

Species which are presumed extinct, endangered or vulnerable on a national basis are listed in

schedules to the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 which came into effect on 30 April

1993 (Table 6). See also Figure 2, a map of threatened Australian plant species.

Table 6

Numbers of endangered, vulnerable and presumed extinct species

in Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Praleclion Act 1992 (at 30 April 1993)

Endangered

Groups

Fish

Amphibians

Reptiles

Birds

Mammals

Plants

Total

7

7

6

25

28

226

229

Vulnerable

Extinct

6

2

15

25

18

660

0

0

0

20

21

74

726

115

Source. Austrahan Nature ConservatIon Agency, /994

Note: There is no /isting/or invertebrates, e.g., insects

Other schedules to this Act provide for listing endangered ecological communities and key

threatening processes. No ecological communities have been scheduled to date although a

discussion paper has been released which outlines the views of the Endangered Species

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

/8

Scientific Subcommittee on the process proposed for listing endangered ecological

communities under the Endangered Species Protection Act (Endangered Species Scientific

Subcommittee, 1995).

Key threatening processes listed in Schedule 3 of the Act are:

•

Predation by the European red fox (Vulpes vulpes);

•

dieback caused by the root-rot fungus (Phytophthora cinnamoml);

•

predation by feral cats;

•

competition and land degradation by feral rabbits; and

•

competition and land degradation by feral goats.

Leigh and Briggs (1992) identified grazing and agriculture, mostly following clearing, as

responsible for well over 90 per cent of plant extinctions and by far the major present and

future threat to plant species classified as endangered nationally.

The question must be asked: when will 'excessive vegetation clearing' be recognised as a 'key

threatening process' in the Commonwealth Endangered Species Protection Act?

Loss of habitat

One of the difficulties in gammg general acceptance of the significance of habitat loss

through clearing arises because a few very obvious animals, including the larger kangaroos

and some parrots, have actually increased in numbers as land has been cleared and pastures

established. The )994 commercial culling quota set by governments for large kangaroos was

4170100.

The land development ethic which prevailed in Australia gave credit to those who cleared the

bush to make way for cows, sheep and wheat. Eucalypts were regarded as the farmer's

enemy_ Before the bulldozer appeared after World War n they had to be removed laboriously

by hand but 'shot up again as soon as your back was turned'.

Hunting individual animal species like the koala and harvesting specific timber species like

red cedar were obvious actions exerting direct pressure on species. By contrast, loss of

habitat is more insidious and less subject to public criticism.

TIlis anomaly is epitomised in the old English verse:

The law goes hard on man or woman

Who steals the goose from offthe common

But lets the greater sinner loose

Who steals the common from the gOOje.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

/9

Activities which foHow clearing such as introduction of exotic crops and grasses. fertilisers.

pesticides. weeds, exotic animals and subsequent increases in erosion and soil salinity all

make it more difficult for remnant habitat to survive and native plants and animals to

recolonise.

Extensive clearing on private land has relegated many rare plants to roadsides where they are

vulnerable to weed competition, changes to the water table, dust, pollution from motor

vehicles and direct damage during vegetation control methods involving mowing and use of

herbicides. Animals sheltering in roadside remnant vegetation are vulnerable to similar

adverse effects and have the added risk of being killed by vehicles.

The koala, one of Australia's national symbols, is a striking example of the impact on species

numbers through loss of habitat. Leaves from only a few species of eucalypt are an essential

component of the koala's diet. Although it will eat leaves of other eucalypts and sometimes

even other types of tree, one or two particular species always fonn the major part of the diet.

Koalas are found natura1ly only in forests containing these particular trees and as forests have

been cleared koala numbers have declined. This is illustrated in Figure 3 showing the

probable range of the koala in 1788 compared to the very limited current distribution.

,

"',

..

.,"

",

pr~blf"ange

Dol ~l.n in 1788

.~pproIim.J11.' curr('fll

d,lol"l>l>llon 1b.1\.<.-d

on siJ:h1inlo-s in r~"Ccnl

N~'ooruJ KU.lI~ Sur'...."1

Figure 3: The distribution oftbe koala

Source: £m>ironmental Science. 1994 Australian Academy a/Sciences.

derivedfrom ECOS 735 Spring /992 CSIRO

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

20

Other threats beside loss of habitat include feral animals and weedy plants. dieback disease.

uncontrolled fire, erosion and soil loss. illegal trapping of animals (particularly birds and

reptiles), illegal harvesting of plants such as orchids and palms. and uncontrolled use of

herbicides.

Feral animals and weeds

About 73 vertebrate animals have been introduced and become established in the wild since

European settlement. In addition, there are many introduced insects, other invertebrates such

as snails, and disease-causing organisms.

Introduced animals which have had major direct effects on native species through predation

include the domestic cat. wild dog and fox. For example, foxes and feral cats contribute

significantly to the endangered status of both malleefowl. Leipaa acellata, and the western

swamp tortoise. Pseudemydure umbrina.

Introduced animals which have destroyed habitat and have thereby adversely affected native

animal species include the rabbit. feral pig. horse, donkey. water buffalo. camel and European

carp. The vulnerable status of the Lord Howe Island Woodhen, Tricholimnas sylverstris. is

due in part to egg predation by rats and habitat damage by pigs and goats introduced to the

island. Similarly. the vulnerable status of the bilby, Macro/is lagatis, is due in part to

competition with rabbits for burrows.

At least 2 000 exotic plants are now a pennanent part of the Australian biota. Ross (1976)

calculated the rate of introduction of non-Australian plant species to Victoria had averaged

five to six species per year over the previous 100 years and there was no sign that this was

diminishing.

The estimated total cost of weeds to Australia annually is $4 DOOm (Australian Horticulture,

1991) and the annual losses due to one species, blackberry, in New South Wales. Victoria and

Tasmania rose from $42m in 1988 to at least $77m in 1990.

These costs relate primarily to the impact on agricultural and pastoral production. However.

some weeds are major problems in conservation reserves and have the potential to reduce

biodiversity through competition. Bitou bush, Chrysanthemoides monilifera, has become a

major problem invading coastal vegetation; giant sensitive plant, Mimosa pigra, has

colonised floodplains in the top end of the Northern Territory; and Athel pine. Tamarix

aphylla. is expanding in some of the dry river beds in Central Australia.

In some cases introduced species may cause genetic contamination. For example, Norfolk

Island pine. Araucaria he/erophylla, is endemic to that South Pacific island and is the only

species of Araucaria occurring there. A small plantation of Queensland Hoop pine,

A.cunninghamii. was established on Norfolk Island but was subsequently removed to prevent

the possibility of hybridisation and consequent genetic contamination of the native Norfolk

Island pine.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

]J

Introduced honey bees may have adverse effects on native bees and pollination of some

native plants. Commercial beehives are now prohibited in some conservation areas.

Leigh and Briggs (1992) estimated that weed competition was the cause of extinction of four

plant species. It was also the past threat to 12 and the present and future threat to 57 species

now classifled as endangered.

Erosion and soil degradation

Soil erosion following a combination of excessive tree clearing, extension of cropping into

marginal lands, droughts and feral animals such as the European rabbit, is the major factor in

soil degradation in Australia. A national survey in 1975 revealed that degradation had

occurred on 55 per cent of the arid zone due largely to deterioration of vegetation followed by

wind erosion. In the non-arid zone 68 per cent of extensive cropping land, 63 per cent of

intensive cropping land and 36 per cent of grazing land had deteriorated to the extent that

remedial work was needed. In present values, the cost of construction works to treat land

degradation is estimated to far exceed $A2 billion (Robert, 1989).

High salt levels are typical of large areas. Salinity problems have been exacerbated by land

management involving removal of tree cover with subsequent rises in the water table. The

problem of high salt levels has increased markedly in irrigated areas and 10 000 sq kIn in the

non-arid zone are considered degraded through salinity.

Fire

Many Australian plants are adapted to fire and may even require burning to open woody

fruits or crack hard seed coats. However, if plants do not have time to mature and produce

seed 'between burns they may be replaced by other species. The fire frequency for heathland

is about ten years and more frequent burning will lead to the disappearance of some heath

plants. Birds such as ground parrots tend to disappear from heath if the fire pattern does not

ensure their food supply.

High intensity wild fires such as those which occurred in New South Wales in 1994 can

destroy local populations of animals unable to fly or flee from the fire. This aspect is

particularly important for sedentary animals in relatively small patches of remnant vegetation

where recolonisation after fire is difficult and any animals which do survive the fire may

starve through loss of food plants.

Dieback disease

Dieback disease caused by the cinnamon fungus, Phytophthora cinnamomi, is widespread

across Australia and is of particular concern in the south-west of Western Australia where it

has spread into some conservation reserves. About 50 per cent of Cape Ie Grande National

Park and more than 20 per cent of Stirling Range National Park are infected. The Western

Australian Department of Conservation and Land Management also estimates that 70 per cent

of Two People Bay Nature Reserve, habitat for the vulnerable noisy scrub-bird, Atrichornis

clamosus, is infected by a combination of dieback and aerial canker.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

22

Dieback fungus attacks plants at their roots preventing uptake of water and nutrients to the

stems and leaves. PI~ls may collapse within two weeks of infection.

It is estimated that 2 000 plant species are threatened including banksias which are important

in the wildflower trade and honey industry and as a food source for many birds and small

mammals.

Cinnamon fungus has already struck heathlanc\s in Tasmania, rainforests in Queensland and, to a lesser

extent, the eucalyptus forests of New South Wales and Victoria. Hardest hit are the jarrah forests of

Western Australia (Sydney Morning Herald. 24 September 1994).

The fungus is spread when infected soil is moved from place to place by bushwalkers,

vehicles, roadworks and even sharp-hoofed feral pigs and native animals with dusty paws.

No cure has yet been found and control centres on quarantining infected areas and complete

washdown of vehicles moving through these areas.

As indicated earlier Phytophthora cinnamomi is listed as a key threatening process in the

Commonwealth Endangered Species Protection Act (1992).

megal trapping

Illegal trapping of fauna and harvesting plants has a severe conservation impact when it is

concentrated on uncommon and threatened species which have special appeal to collectors

because of their rarity. There is often associated cruelty to animals when attempts are made

to hide them during transport either within Australia or to overseas destinations. Birds and

reptiles are the main animal targets while orchids from North Queensland have a ready

market overseas.

Conserving biodiversity

Plant communities

Much of the effort in biodiversity conservation has been directed. at identifying and protecting

rare and threatened. species. Without this effort more species would become extinct and there

are very few people who would consciously wish to add to the number of species now known

only from herbarium and museum specimens. Australia already holds the record for the

highest number of mammal extinctions of any country. a record which cannot be held with

any pride.

In general, public sympathy and support is easier to muster for an endangered species than an

endangered community. This explains in part why public appeals to save the helmeted

honeyeater, Lichenostomas me/anops cassidix, or the northern hairy-nosed wombat,

Lasiorhinus krefjiii, are more successful than appeals to conserve the community or habitat

where they live. Sometimes of course, an animal can be a focus of interest for habitat

conservation as in the case of the long-footed potoroo, P%rous /ongipes, in the south-eastern

forests of New South Wales.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

23

Emphasis on species conservation has, however, overshadowed the need for community

conservation and more attention must be given to this aspect in the interests of conserving

biodiversity.

The importance of community conservation is evident in the example of the interaction of the

sugar glider, black wattle, apple box and scarab beetle. Sugar gliders are common in eucalypt

forest and woodland although being nocturnal, they are not often seen. They feed on scarab

beetles, eating up to 1S large adults per hour at night when the beetles are active. Scarab

beetles feed voraciously on eucalypt foliage, sometimes causing defoliation.

Their

appearance is seasonal, however, and sugar gliders must have alternative food when scarab

beetles are absent. Research in Victoria has shown that gums produced by black wattle and

apple box are the major food for sugar gliders in winter. Tree hollows, groundcover,

flowering trees and shrubs also improve the habitat for gliders although without black wattle

they will not survive through winter. In the absence of gliders, scarab beetles may increase in

numbers to the point where trees are defoliated and dieback sets in (Smith, 1993). If trees

die, the watertable rises, bringing salts to the surface and resulting in soil degradation and

poor quality runoff water.

Major advances in developing techniques for direct sowing of native seed mixtures

helped to improve opportunities to reconstruct plant communities but we need to learn

about seed ripening times and gennination requirements There are major long

biodiversity advantages in attempting to restore communities rather than replanting

alone.

have

more

tenn

trees

Research and survey

Research and survey is fundamentally important to Australian nature conservation.

Universities, museums, herbaria, zoological and botanical gardens, various divisions of

CSIRO and territory, state and Commonwealth departments all play important roles with

funding provided by governments directly and through private agencies such as the

Worldwide Fund for Nature.

Much of Australia's biodiversity is still not studied (Richardson, 1984). More than SO per

cent of the estimated 200 000 Australian invertebrate species and 2S per cent of higher plants

remain to be described. Historically, scientific effort has been concentrated on conspicuous

elements of the flora and fauna. Organisms such as fungi, protozoa and arthropods which are

fundamental to the function of terrestrial ecosystems have been ignored.. These organisms are

integral to such diverse functions as biogeochemical cycles, nutrient uptake, maintenance of

soil fertility and pollination (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment,

Recreation and the Arts, 1992).

Some conservation reserves have been established without detailed surveys of flora and fauna

within them. Such surveys are essential as a basis for monitoring the effects of management

to ensure that the values which justify reservation are being retained.

Surveys may uncover unknown species, greatly enhancing the scientific value of the reserve.

The recent discovery of a previously unknown species of native conifer in a secluded gorge in

the Wollemi National Park in NSW is a prime example (The Canberra Times 1S December

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

24

1994). There appear to be only forty specimens of this tree whose closest relatives are fossil

Araucarites known only from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods 200 to 65 million years

ago. This discovery is as significant to science as that of the dawn redwood, Metasequoia

glyptostroboides, in a remote valley in China in 1941. Millions of dawn redwoods are now

grown as ornamental trees and Wollemi pine may have similar potential.

Volunteers are playing an increasing role in research and survey work. The Atlas of

Australian Birds produced by the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union in 1984 was based

on observations by more than 3 000 volunteers 'who had passively watched birds in their own

backyards from Cairns to Perth, Wyndham to Oodnadatta' and then 'trekked into the outback'

(Blakers, Davies, Reilly, 1984).

The Western Australian Department of Conservation and Land Management now runs a

program where volunteers actually pay for the opportunity of joining expeditions to work

with research scientists in the field.

One of the consequences of having such a diverse flora and fauna with so many endemic

species is that ecological and conservation based research must be carried out in Australia. It

cannot be carried out in other countries.

Apart from the human 'need to know' which has always driven inquiry. competent research

and implementation of findings is an investment in ensuring that Australia's biodiversity

continues to anract international tourists.

International conservation agreements

Australia's strong commitment to international conservation agreements since the 1970s has

often been clouded in controversy over 'states' rights' although supported in principle.

A list of agreements to which Australia is a party (Appendix) is a measure of national and

international concern for nature conservation. It is also clear recognition that, despite our

geography, Australia is part of the world scene where migratory birds and marine species and

international trade in wildlife are concerned.

Implementation of these agreements is provided for in nature conservation legislation which

regulates management of conservation reserves and protection of native plants and animals

both in reserves and on other public and private land.

Parks and reserves system

The national parks and reserves system on public land which began in earnest with the

establishment of Royal National Park south of Sydney in 1879, the second only in the world, is a

fundamental component of conservation of biological diversity. In fact, it 'is the major tool

presently available to protect biodiversity' (Flannery, 1994).

The reserve system has grown remarkably in the last 115 years and now covers 50 million

hectares or about 6.4 per cent of the country. Like many other activities in Australia, the pattern

of development varied from state to state and there was no national approach. In some cases,

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

25

reserves stopped at a state border even though the same habitat continued into the adjacent area

and was in equal need of protection.

Attempts to examine the adequacy of the reserve system in covering the diverse range of

ecosystems have long been made by academics and organisations like the Australian Academy

of Science. It was not tackled at the parliamentary level, however, until 1970 when the House of

Representatives established a Select Committee to inquire into the state of wildlife conservation

in Australia.

The Select Committee considered the adequacy of the national park and reserve system and

recommended:

That a national policy be initiated aimed at acquiring such portion of the total land area of each State and

Territory in the fonn of secure national parks and reserves as will ensure that all habitat types will be

preserved (Recommendation 2(a), House of Representatives Select Committee on Wildlife Conservation,

1972).

The area of national parks and reserves at 30 June 1972 was 16 001 921ha or 2.1 per cent of

the country. Although it now occupies 6.4 per cent it still does not fully represent the range

of Australian biodiversity.

In 1993 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment, Recreation and

the Arts inquired into the role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity. The Committee

heard evidence of major gaps in the system and recommended:

that, in setting up a core protected area system nationwide, the Commonwealth set as a minimum

target the representation of at least 80 per cent of bioregional ecosystems in core protected areas by the

tum of the century (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment, Recreation and the

Arts, 1993.)

(7)

The Committee recognised a need for definition and agreement between the States,

Territories and the Commonwealth on the range of bioregions and urged the Australian and

New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council, ANZECC, to address this.

An Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia, IBRA, project has been initiated by

the Australian Nature Conservation Agency working with State and Territory agencies and

80 bioregions identified (Thackway and Cresswell, 1995). When these are validated and

overlaid by the existing reserve system they will form an agreed basis for determining

priorities in land reservation for Commonwealth funding under the National Reserves

System Cooperative Program, NRSCP (ANCA, 1994).

Other public lands

The great diversity which exists in Australian flora and fauna together with the fact that

many species occupy small ranges scattered across the continent mean that:

To protect all biodiversity within reserved lands would require a huge increase in the reserved lands

system (Flannery, 1994)

This is not likely to occur, and other means of conserving biodiversity will need to be found.

Society will also have to make some difficult decisions on the amount of biodiversity which

is needed or can be afforded.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

26

While national parks and nature reserves are the mainstay of nature conservation, other

public lands (and private lands, see below) have important roles to play. Forestry legislation

in all states provides for areas within state forests to be set aside for special purposes

including conservation of flora, fauna and landscapes (Boden, )984). In some cases the

areas are regarded as reference stands which can be used to assess the effects of forest

management. In others, they have been established to protect rare species. For example, the

Bunal Forest Preserve near Inverell in NSW contains Baker's mallee, Eucalyptus bakeri, and

several other unusual tree occurrences; and the Whipstick Forest Park near Bendigo in

Victoria includes the rare Whirrakee wattle, Acacia williamsonii.

Road and rail easements are significant areas of public land. In Victoria, for example, roads

occupy about 2.5 per cent of the state. In 1987 there were 870 OOOkm of roads in Australia.

While a large part of the road reserve is dedicated to its primary purpose of carrying traffic,

there are often extensive verges in rural areas which are important habitat for plants and

some animals.

Remaining native vegetation on roadsides often provides evidence of the type of vegetation

which occurred before adjacent paddocks were cleared and is therefore a useful guide to

rehabilitation programmes. They are also seed reservoirs for revegetation projects if

harvested carefully. A measure of the importance of road and rail reserves as habitat for

threatened plants lies in the fact that roadworks are the major threat to 61, or more than a

quarter of species classified as endangered (Leigh and Briggs, 1992).

Linear easements, including fonner stock routes, act as corridors for wildlife movement and

may be particularly important in assisting some species to move from areas which are burnt.

Sugar gliders have been known to disperse more than one kilometre along roadside corridors

and can survive at high densities in linear forest habitats of little more than a single tree in

width. Ironically, they may initially survive better than the trees themselves which suffer

when reduced to a thin band exposed on both sides.

The significance of road easements for biodiversity conservation has been recognised by the

Australian Road Research Board which has prepared a draft National Strategy for Roadside

Reserve Management (Farmar-Bowers, 1994).

Private and leasehold land

The area of nature conservation reserves on public land has increased markedly in recent

years. 1bis often appears to be stimulated by imminent elections suggesting the political

importance attached to this aspect of nature conservation. Unfortunately, additions to the

reserves system have occurred at times of shrinking management resources, including staff

numbers. There is therefore a growing perception that present reserves are not adequately

managed. This has increased opposition among some rural communities to further

acquisitions.

Under these circumstances, innovative ways need to be found to encourage landholders to

manage native vegetation on their land for conservation rather than relying only on the

public reserve system.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

27

Two-thirds of the State of Victoria is privately owned and some of it contains important

habitats not represented on public land. Between 80 and 95 per cent of the original native

vegetation in the wheat belt of NSW has been cleared and what little remains is on private

land (Sivertsen, 1994).

A Land for Wildlife Scheme has now been operating successfully in Victoria for several

years. Over 2 500 properties covering more than 270 OOOha of private land of which some

5 000 - 7 OOOha are managed for wildlife, are participating. The brolga, Grus rubicundus, is

a majestic bird standing up to 1.4 metres tall and living for forty years. It fonnerly occurred

in large numbers in Victoria but only about 600 birds now remain there. About a third of

this population migrates each year to the southern Grampians in Western Victoria where

they forage for fallen grain and insects in stubblefields after the wheat, barley and oats have

been harvested. Pizzey (1994) believes these birds rely:

... for nearly six months every year on the tolerance, goodwill and generosity of a few dozen private

landholders.

The display perfonned by this magnificent bird is as elegant as Graham Pizzey's eloquent

description of it:

As they drop steeply to earth with raised necks and lowered legs, several indulge in wild aerobatics.

Once down, they leap and bow, toss tufts of straw in the air, go bounding off with widespread

wings...For brolgas. and everything a brolga does is touched with a wild spirit.

While it is appreciated that this type of conservation is species rather than communityoriented, it is biologically significant for a nomadic or migratory species like the brolga and

valuable in stimulating public interest in wildlife conservation.

The 'stick' approach to protecting native vegetation on private land comes from controls on

land clearing. South Australia pioneered the concept of clearance controls and voluntary

Heritage Agreements in the Native Vegetation Management Act 1985. This legislation was

replaced by the Native Vegetation Act 1991 which controls the clearance of native vegetation

as well as having a number of initiatives to assist conservation, management and research of

native vegetation on lands outside the declared parks and reserves system.

An analysis of the perfonnance of the scheme since it was introduced in 1985 has recently

been prepared by J R Bradsen, Chainnan of the (SA) Native Vegetation Council, which is

responsible for decisions on clearance applications and for providing advice to the Minister

of Environment and Land Management on the condition of native vegetation in South

Australia (Bradsen, 1995).

An integral part of the legislation provides for Heritage Agreements between the landowner

and the State Government for the protection in perpetuity of a particular area of native

vegetation. The landowner retains ownership of the property and there is no right of public

access without landowner approval. In return for entering into the Heritage Agreement the

landholder may be compensated for the cost of fencing to protect the area from grazing, may

be released from rates and taxes on the land, and may receive some management assistance

through the Native Vegetation Fund.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

28

By 1994 more than 850 agreements had been signed for the protection of 550 OOOha of

bushland. Areas of land covered by individual agreements range in size from about two

hectares to 10 OOOha with an average size of about 400ha. Assuming a natural stocking rate

of between 300 and 400 trees per hectare this amounts to saving about 200 million trees and

the associated understorey.

Some other states have introduced similar schemes and the Australian and New Zealand

Environment and Conservation Council has recently established a working group to develop

a coordinated national approach to nature conservation on private land. One scheme to be

assessed for suitability to the Australian scene is the Ecological Sensitive Area concept now

being applied in the European Union (Bridgewater, 1994).

In South Australia over $70 million in financial assistance has been paid to landowners who

have entered into heritage agreements to save bushland on their fanns. This may seem a

high figure but it is only about 35 cents per tree saved. It is less than the cost of planting and

has the added benefit of saving the interacting plant and animal community.

The tenn intergenerational equity has now joined biodiversity as part of the common

language. Stated simply, it means ensuring that children and grandchildren inherit a country

as rich and diverse as their parents and grandparents did. The ethos of intergenerational

equity, which most Australians know better as 'wanting to look after the kids', is expressed

most strongly in times of war. It should be expressed equally strongly now in the battle to

conserve biodiversity.

Australian Biodiversity Under Threat

29

References

Annstrong, J and Hooper K (1994), Nature's Medicine Landscape 9:4 ppI0-15.

AUSLIG (1990), Atlas afAustralian Resaurces, Third Series, Val 6: Vegetatian. Austrnlian

Surveying and Land Information Group, Canberra p 64.

Australian Academy of Science (1994), Environmental Science.

Science, Canberra p 465.

Australian Academy of

Australian Horticulture (1991), Beating the dreaded blackberry Australian Horticulture 89:5

p66.

Australian Nature Conservation Agency (1994), Annual Repart 1993-94, AGPS, Canberra

p159.

Blakers, M., Davies, S.J.J.F., and Reilly, P.N. (1984),

Melbourne University Press, Melbourne p738.

The Atlas af Australian Birds,

Boden, R.W. (1994), Special Purpose Forest Reserves and their role in Protecting

Endangered Plants, Habitat 12;5 PP 12-14.

Bradsen, l.R. (1995), Vegetation Clearance Controls in South Australia, (in press)

Bridgewater, P (1994), Epilogue: some concluding observations, p 217-219 in Future ofthe

Fauna of Western New South Wales, eds. Lunney, D., Hand, S., Reed, P., and Butcher, D.,

Royal Zoological Society ofNSW, Mosman.