* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Off-label antibiotic use in children in three European countries

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of cephalosporins wikipedia , lookup

Clinical trial wikipedia , lookup

Drug discovery wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacognosy wikipedia , lookup

Medical prescription wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Prescription drug prices in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Electronic prescribing wikipedia , lookup

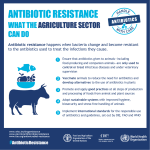

Antibiotics wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

List of off-label promotion pharmaceutical settlements wikipedia , lookup