* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

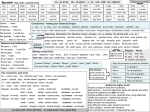

Download Hablando de gramática

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Comparison (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish verbs wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Hablando de gramática por el señor Conner WWW.TOBREAK.COM John Conner is the author of the popular language series Breaking the Spanish Barrier and the newly released OASIS, handy phrase book/dictionary with audio CDs. Each month he features a grammatical topic of interest to our readers. Have ideas of topics you would like to see covered? E-mail Señor Conner at [email protected]. You can also visit his website www.tobreak.com. Whenever I am in the presence of native Spanish speakers, I am amazed at how effortlessly “refranes” and “dichos” flow from their lips. These time-tested refrains and adages offer wonderful reflections on life. I often pull out a notecard I keep in my back pocket so that I may catalogue some of my favorites. It is clear to me that these expressions have traveled from mouth to mouth over time, in part, because of the beauty of the expressions themselves: the choice of vocabulary, the flow of the words, and the rich grammar. A number of years ago, I wrote an article for Think Spanish about some of these refrains. For this month’s column, I have chosen all new ones. Let’s take a look at a dozen, seeing what they mean, and analyzing the grammar a bit. POPULAR SAYINGS AND ADAGES Chock-full of great grammar 1) Caminito comenzado, es medio andado. Well begun is half done. (Literally: A path that is begun, is half walked.) NOTE: Past participles serve as adjectives here – “comenzado” and “andado.” “Medio” is an adverb, modifying the adjective “andado.” 2) Aunque la mona se vista de seda, mona se queda. You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. (Literally: Even though a monkey may dress in silk, it is still a monkey.) NOTE: The subjunctive that follows “aunque” is used to convey the idea of “may” or “might.” The preposition “de” is often combined with a noun to tell what something is made of: “de algodón,” “de cuero,” etc. 3) Cuando el gato está ausente, los ratones se divierten. When the cat’s away, the mice will play. (Literally: When the cat is absent, the mice enjoy themselves.) NOTE: “Estar” is used rather than “ser” to describe a “condition” – the cat’s being away. “Divertirse” (to enjoy oneself) is a reflexive, stem-changing verb. 4) Cuando pases por la tierra de los tuertos, cierra un ojo. When in Rome, do as the Romans. (Literally: When you pass through the land of the Cyclops, close one eye.) NOTE: The subjunctive of “pasar” is used after the adverb “cuando” because it refers to a future action. “Cierra” is the (tú affirmative) command form of “cerrar.” 20 julio de 2010 5) Del dicho al hecho hay mucho trecho. Easier said than done. (Literally: From saying to doing there is a long distance.) NOTE: The past participles of two verbs (“decir” and “hacer”) serve as nouns here when coupled with the definite article “el”. 6) Dos no riñen si uno no quiere. It takes two to tango. (Literally: Two don’t argue if one doesn’t want to.) NOTE: “Reñir,” meaning “to argue, to scold,” is an –IR stem-changer. There aren’t many infinitives that end in “ñir.”“Teñir,” meaning “to dye,” is another. 7) El empezar es el comienzo del acabar. By taking the first step, you are halfway there. (Literally: Beginning is the start of ending.) NOTE: The infinitive, often paired with a definite article, serves as a noun. In English, we would tend to use an –ing form (Beginning à El empezar) 8) El que ríe último, ríe mejor. He who laughs last, laughs best. (Literally: The same!) NOTE: The subject here is indefinite. “El que” can refer to any person. The infinitive “reír” is an –IR boot verb: río, ríes, ríe, reímos, reís, ríen. 9) Hay que romper el huevo antes de hacer la tortilla. Take one step at a time. (Literally: One must break the egg before making the omelette.) NOTE: Two great uses of the infinitive are highlighted here: a) An infinitive follows the construction “hay que” indicating that one must do something; b) An infinitive will be used after a preposition (antes de) – in English we would use the –ing form. 10) La esperanza es la última cosa que se pierde. Hope is the last thing to die. (Literally: Hope is the last thing that is lost). NOTE: This “refrán” is full of great grammar. A definite article starts the sentence as the speaker is talking about “hope” in general. The adjective “última” is an ordinal adjective modifying“cosa” and comes before it, as many ordinal adjectives do; finally, the use of “se” before “pierde” indicates there is no definite subject for the verb “perder” ... this is an example of the impersonal “se.” 11) La fortuna es un montoncillo de arena; un viento la trae y otro se la lleva. Good fortune is fleeting. (Literally: Fortune is a mound of sand; a gust of wind brings it and another takes it away.) NOTE: The diminutive ending “cillo” indicates that it is a little mountain (mound) of sand; in “la trae,” “la” is a direct object pronoun as is the “la” in “se la lleva.” 12) Más hace el lobo callando que el perro ladrando. At times, silence is best.(Literally: The wolf does more staying quiet than the dog barking.) NOTE: The present participles in this sentence (callando and ladrando) have an adverbial use … indicating what each animal does.The rhyme makes the sentence memorable. w w w .thinkspanish.com 21 PRUEBA DE REPASO Which “refrán” from this lesson might you say to a friend who said the following to you? a) “Mi amiga habla y habla y habla, pero nunca, nunca hace lo que dice que va a hacer”. b) “Como ahora estamos en Lisboa, ¿no crees que sería mejor hablar en portugués?” c) “Cuando mis padres se fueron de vacaciones, mis amigos y yo la pasamos súperbien en casa”. d) “Tengo un montón de tarea y nunca podré terminarlo todo. Es inútil … no tengo ganas ni de empezar”. e) “Mi amigo siempre gana cuando jugamos al tenis. Él siempre se burla de mí, pero voy a seguir practicando. Un día de estos verá que …” f) “Esos chicos se pusieron ropa muy elegante, pero cuando entraron en el restaurante de lujo no tenían ni idea de qué pedir, qué cubierto usar … es decir, ¡de nada!” g) “¡Qué suerte tengo! He ganado la lotería, mi novia me ha enviado un regalo y el profesor canceló el examen de mañana!” h) “No es mi culpa. Mi amigo siempre hace cosas tontas y por eso peleamos constantemente”. i) “Mi papá no dijo ni una palabra. Sólo me miró. Pero yo sabía exactamente lo que estaba pensando”. ANSWERS a) Del dicho al hecho hay mucho trecho. b) Cuando pases por la tierra de los tuertos, cierra un ojo. c) Cuando el gato está ausente, los ratones se divierten. d) El empezar es el comienzo del acabar /Hay que romper el huevo antes de hacer la tortilla. e) El que ríe último, ríe mejor. f ) Aunque la mona se vista de seda, mona se queda. g) La fortuna es un montoncillo de arena; un viento la trae y otro se la lleva. h) Dos no riñen si uno no quiere. i) Más hace el lobo callando que el perro ladrando. 22 julio de 2010