* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

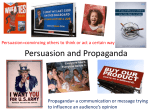

Download What Is Propaganda, and How Does It Differ From Persuasion?

International broadcasting wikipedia , lookup

Propaganda in the Mexican Drug War wikipedia , lookup

German Corpse Factory wikipedia , lookup

RT (TV network) wikipedia , lookup

Propaganda of Fascist Italy wikipedia , lookup

Political warfare wikipedia , lookup

Eastern Bloc media and propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Role of music in World War II wikipedia , lookup

Propaganda in Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II wikipedia , lookup

Cartographic propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Airborne leaflet propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Architectural propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Propaganda in Nazi Germany wikipedia , lookup

Randal Marlin wikipedia , lookup

Radio propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Psychological warfare wikipedia , lookup