* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Short Introduction to the Paradoxical and

Interfaith marriage in Judaism wikipedia , lookup

Jewish religious movements wikipedia , lookup

Jewish military history wikipedia , lookup

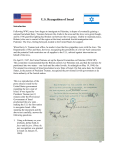

Land of Israel wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on religious pluralism wikipedia , lookup

Haredim and Zionism wikipedia , lookup

Israeli Declaration of Independence wikipedia , lookup