* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 53: Causes and consequences of inflation and

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Real bills doctrine wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Helicopter money wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

Long Depression wikipedia , lookup

Nominal rigidity wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Phillips curve wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Money supply wikipedia , lookup

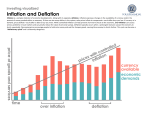

Chapter 53: Causes and consequences of inflation and deflation (2.3) Key concepts Causes of inflation o Demand pull inflation o Cost-push inflation o Excess money supply Causes and consequences of deflation Counter-inflationary policies Evaluation of counter-inflationary policies Consequences of deflation • Discuss the possible consequences of deflation including high levels of cyclical unemployment and bankruptcies Types and causes of inflation • Explain, using a diagram, that demand pull inflation is caused by changes in the determinants of AD resulting in an increase in AD • Explain, using a diagram, that cost-push inflation is caused by an increase in the costs of factors of production resulting in a decrease in SRAS • Evaluate government policies to deal with the different types of inflation “Having a little inflation is like being a little pregnant – inflation feeds on itself and quickly passes the ‘little’ mark.” Dian Cohen. Causes of inflation Two main causes of inflation are Keynesian in origin; cost push inflation arising from higher factor costs to firms, and demand-pull inflation which arises when aggregate demand in the economy outstrips available aggregate supply. A third, neo-classical/monetarist view, posits that inflation is demand-pull in nature, but that it is the underlying variable of increased money supply which is the root cause. o Demand pull inflation Aggregate demand might rise for a number of reasons; stimulatory monetary/fiscal policies, greater consumer confidence, ‘animal spirits’ of firms…etc. Demand-side shock, A to B: When aggregate demand increases swiftly in the short run due to, say, greater demand for exports, there will be a demand-side shock and concomitant (= associated) increase in the price level, shown in figure 53.1 (diagram I) as the shift form AD0 to AD1. [And again, this is a perfectly acceptable way to illustrate demand-pull inflation!] Figure 53.1 Demand-side shock, demand-pull inflation and demand-pull spiral ↓ ↑ Demand-pull inflation, A to D: Once again, the initial increase in the price level (P0 to P1) due to increased aggregate demand does not mean inflation per definition, but might rather set the stage for demand-pull inflation. o Diagram II in figure 53.1shows how inflationary expectations cause aggregate demand to feed on itself, as firms’ and households’ spending plans increase in anticipation of higher future prices. Aggregate demand increases further, from AD1 to AD2, and the price level increases to P2. o This is untenable (= unsustainable) in the long run, since higher final prices cause labourers to suffer real wage loss, and subsequently they start to bid up wages. o This results in higher labour costs for firms and a decrease in aggregate supply from SRAS0 to SRAS1. The economy has moved towards long run equilibrium (YNRU) but at a higher price level, P3. The original shift in AD sets off a round of demand-pull inflation where aggregate demand increases beyond long run potential output. Demand pull spiral, D to H: If aggregate demand continues to rise – due to continued expectations of high inflation – then the economy can expect a process where prices increase labour adjusts by bidding up wages and firms scale back on production due to lower margins between input prices (e.g. labour costs) and final output prices. This is a demand-pull spiral, as illustrated in figure 53.1, diagram III. o Cost-push inflation An increase in factor costs on a macro scale can cause prices to rise due to the increase in costs. This causes cost-push inflation and is frequently associated with ‘one-off’ increases in price level, known as supplyside shocks. There are a number of possible causes of cost-push inflation; wages rising faster than productivity gains in the economy; a fall in the exchange rate driving up the price of imported raw materials and components; or an increase in factor prices, say the price of oil. All of these will shift aggregate supply to the left, shown in diagram I, figure 53.2. Figure 53.2 Supply-side shock, cost-push inflation and cost-push spiral ↑ ↑ ↑ Supply-side shock, A to B: The price increase in key factors of production shifts the short run aggregate supply curve from SRAS0 to SRAS1 (diagram I, figure 53.2) which increases the price level from P0 to P1. This combination of a fall in output and inflation is known as stagflation (i.e. stagnating and inflationary economy). [Note: many textbooks and teachers use diagram I to illustrate cost-push inflation. This is perfectly acceptable!] Cost-push inflation, A to D: Technically speaking, the supply-side shock illustrated in diagram I does not comprise inflation, since it is a one-off increase rather than consistent. One could say that the supply shock “sets the scene” for cost-push inflation: o When labourers realise that real wages have fallen due to a higher price level, individual wage bargaining and unions will drive up wages to regain lost purchasing power. o The higher cost of labour will shift aggregate supply even further to the left, from SRAS1 to SRAS2 in figure 53.2, diagram II. The price level rises from P1 to P2. o Ultimately, the increase in wages (perhaps accompanied by expansionary policies in order to countermand increased unemployment) increases consumption and increases aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1. The increased spending (and possible expansionary policies) move the economy towards equilibrium at YFE but at a higher price level. We have now had a round of cost-push inflation. Cost-push spiral, D to H: Now, consider that final prices have risen to P3 (now continued in diagram III in figure 53.2) due to increased consumption and fiscal stimuli. Real wages have once again fallen due to the effects of inflation. Another period of bidding-up wages could lead to a further decrease in aggregate supply, shown by the shift from SRAS2 to SRAS3, and another round of cost-push inflation. Diagram III shows how successive shifts in SRAS and AD create an upward spiral, known as a cost-push spiral or wage-price spiral. The basic effect is; price level wages costs to firms price level …etc. (Type 5 Smallest heading) The (in-) famous 1970’s cost-push spiral The most (in-) famous of supply-side shocks occurred during 1973 and ’74 when OPEC managed to force oil prices upwards by 300%, the first oil crisis. Oil is vital to production since it provides energy, transportation, compounds for plastics etc, and when the price of oil quadrupled, firms’ costs increased greatly, causing a severe supply shock and stagflation in most industrialised countries. When stagflation hit industrial countries, many responded by stimulatory policies which drove prices higher and resulted in costpush inflation. Many countries saw repeated rounds of higher costs and wages which led to cost-push spirals. The effect on the global economy was tremendous, with falling output levels and rising unemployment in most of the world. It also spelled the end of pure Keynesian demand-side policies; see long run Phillips curve following. As a most illuminating final footnote; recently declassified documents (December 2003) in Great Britain paint a most illustrative picture of just how serious the oil crisis was regarded by the President of the US in 1973/’74, Richard Nixon. In a copy of a report sent to British Prime Minister Edward Heath (dated 12th December 1973), Nixon put forward serious plans for the military occupation of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Abu Dhabi. 1 Perhaps the world is lucky that Nixon got his hands tied by the Watergate scandal around the same time. o Excess money supply Assume an economy with only one firm, which produces 1,000 Widgets per year at a price of $1 per Widget. Additionally, the supply of money is $1,000. Assuming all Widgets are sold, what is national income? Easy; it’s $1,000 – the same amount spent (E) and earned (Y) on output (O). What if the supply of money doubled to $2,000 but output remained the same? Quickly check Section 3.1 (Nominal and real income) to realise that nominal national income will increase but real income will remain the same. Assuming that the additional $1,000 flows around the economy at the same rate as the original $1,000, we can also fairly safely assume that the price of Widgets goes from $1 to $2 – the price level has doubled.2 1 IHT, January 2 2004, page 5; US considered seizing Arab oil fields. 2 Dear colleagues, I am aware that I am cutting a few corners in the cornerstones of the quantity theory of money and the Fischer equation. However, what if the ability of the firm to produce Widgets also increases during the time period, say that new technology and production methods enables the firm to produce twice as many Widgets at the same cost as before? Assuming that all are sold and that, once again, people use their notes and coins at the same rate as before, the price of Widgets will remain at $1, and real income will double to $2,000. The above is a highly simplified and of course exaggerated example of how excess money supply causes demand-pull inflation.3 Neo-classical/ monetarist economists view inflation as primarily demand-driven and caused by an increase in the supply of money (i.e. monetary growth) above and beyond the long run ability of the economy to increase the supply of goods – LRAS at the natural rate of unemployment (NRU). In simple terms; if the increase in the supply of money is above productivity gains the result will be inflation. The mechanism herein can be explained by the monetary transmission mechanism. (Type 3 Medium heading) The monetary transmission mechanism Monetarists view inflation as primarily caused by demand-pull, often phrased as ‘too much money chasing too few goods’. One of the pillars of monetary theory is the overriding importance attached to the supply of money in the economy. Monetarists view the demand for money as relatively inelastic, so an increase in the supply of money will have a large impact on firms’ investment and households’ consumption via falling interest rates. The series of diagrams in figure 53.3 illustrate how an increase in the supply of money and lower interest rates feed through to an increase in investment and aggregate demand in the short run. Diagram I: Increasing the supply of money from Sm0 to Sm1 forces interest rates down from r0 to r1. Diagram II: Lower interest rates induce an increase in investment, which is shown by the movement along the investment schedule. Investment increases from I0 to I1. Diagram III: The increase in investment causes an increase in aggregate demand; AD0 to AD1. This is the transmission mechanism, where an increase in the supply of money is “transmitted” to an increase in real output. (There is also a direct link between the lower interest rate and greater household expenditure which also fuels aggregate demand.) In summa: ↑∆Sm → ↓∆r → ↑∆I and ↑∆C → ↑AD and ↑∆ price level (inflation) The resulting inflation caused by increased money supply can thus be viewed as ‘...too much money chasing too few goods’. 3 For more depth on this – outside the syllabus (and this book) – look up ‘quantity theory of money’ and/or ‘the Fisher equation’. Figure 53.3 The (monetary) transmission mechanism (Type 3 Medium heading) The neo-classical view of money-driven inflation – LR effects It is important to realise that monetarist theory views any increase in money that is not matched by an increase in real potential output (LRAS) as being solely inflationary in the long run. As the increase in AD (figure 53.3) has pushed equilibrium output beyond LRAS, the increase in real GDP shown in diagram III will not last, since wages will rise to match labour demand, serving to increase costs for firms and thus push the AS curve to the left (SRAS0 to SRAS1) as in figure 53.4. Output returns to the natural level of output, YNRU but at a higher price level. Milton Friedman coined a main monetarist article of faith by stating that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. 4 4 One of my many cheeky students, Ms O’Connor, once sent me a picture of two machines; one had numerous dials, knobs, levers, wires, connections, scales and indicators on it while the other machine had a single button, ‘On-Off’. The first machine was labelled ‘Woman’ and the second ‘Man’. I often think of monetarist policy as a ‘Man’ machine, since all the various forms of fiscal policies are basically replaced with a single knob labelled ‘Money: More Less’. Figure 53.4 The (monetary) transmission mechanism While I am oversimplifying, the basic idea of steering the economy primarily by regulating the money supply is in keeping with neo-classical theory since it advocates minimum government intervention in favour of a few simple rules and guidelines such as the Central Bank openly setting target rates of monetary growth and allowing the economy to adapt in terms of inflation and output. (See Chapter 59 for some depth on monetary policies available to the central bank.) Alternatively, the Bank can set inflation ceilings and then adjust money supply to keep inflation under control. A common ‘rule of thumb’ – simple but quite effective in fact – is that monetary policy should be tightened when nominal interest rates are lower than nominal GDP growth and vice versa. POP QUIZ 3.5.4: CAUSES OF INFLATION 1. Why might governments in high inflation countries actually gain from the effects of inflation? Hint; governments issue bills and bonds to borrow money. 2. An economy ‘imports’ inflation due to the increase in price of irreplaceable raw materials. Unions push for higher wages to counter the cost of living increase and…now what? Use a diagram to explore possible outcomes. 3. Over a five year period, the following changes are noted in an economy: Time period t1 t2 Increase in money supply 7.0% 10.5% Inflation 6% 6.5% Real GDP growth 4% 2.8% t3 t4 t5 18.4% 9.6% 9.0% 8.5% 11.5% 10.5% 1.4% -0.8% -1.5% Use the viewpoint of a neo-classical/monetarist economist to explain the pattern of inflation rates and growth during the five year period. Causes and consequences of deflation “Inflation is taxation without legislation.” Milton Friedman Deflation can be good, bad, and pretty darned ugly. Economists commonly differentiate between two types: 5 Good, or benign, deflation: This is caused by an increase in aggregate supply. Diagram I in figure 52.1 shows how the price level falls when short run aggregate supply outpaces demand; the price level falls from P0 to P1. Such deflation might result from increasing productivity and cannot be considered harmful since the economy is growing and real incomes are increasing. In reality, disinflation (falling inflation rates) has become the norm in industrialised countries, where average inflation was 5% during the 1980s but had fallen to around 2% by the end of the ’90s. 5 Bad, or malign deflation: However, if the price level falls due to a decrease in aggregate demand, as in diagram II, figure 52.1, there can be serious and long-lasting negative consequences for the economy; malign deflation. An economy experiencing a recessionary period that becomes protracted might cause households and firms to decrease consumption and investment to ride out the bad times and wait for the good times. This can actually prolong the recessionary period when households and firms decrease expenditure in favour of saving. Remember, a fall in the price level will increase the value of money. If households expect prices to continue to fall they will put off expensive purchases in order to get more for their money. This fall in aggregate demand can therefore confirm firms’ beliefs that less investment is necessary which together with the decrease in consumption can become self-reinforcing in the economy. IHT, A new economic era – A global shift to deflation, May 22, 2003 Figure 53.5 ‘Benign’ and ‘malign’ deflation One might say that malign deflation cures inflation something like lung cancer cures smoking and I dare say that most economists would agree that deflation is a far greater threat to economic stability and growth than inflation. The self-reinforcing loop – known as a deflationary spiral – created by falling prices expectations of falling prices lower aggregate demand falling prices…etc is a most powerful force for fiscal and monetary policy to overcome. In fact, many textbooks use the Great Depression of the 1930s to describe the effects of continuously falling aggregate demand and resultant deflation. As prices, expenditure, output and incomes fall there will be increasing unemployment which further dampens aggregate demand and can quite possibly become permanent as some sectors fold and others see permanent reductions in demand. This might lead to a higher natural rate of unemployment. It seems that deflation, once it becomes entrenched (= deeply rooted) cannot be dealt with easily. The ‘trick’ is to create inflation by increasing the inflationary expectations of households and firms, but the severity of the situation seems to resist standard monetary and fiscal policies. The solutions offered can therefore be at the extremist end of policy-making, where common suggestions involve some or all of the following: quickly lowering interest rates (see liquidity trap in Chapter 59) as soon as prices show a tendency to fall; very publicly announcing that the Central Bank has increased the target rate of inflation; large scale purchasing of bonds to create additional liquidity on the market; depreciating/devaluing the currency to increase exports; and printing “funny money”, i.e. printing consumption certificates which can only be used for consumption and then sending them to households in order to boost consumption and aggregate demand.6 6 In fact, Milton Friedman’s tongue-in-cheek suggestion for solving deflation was for the government to print money and fly around in helicopters and unload the bills on a happy citizenry – the bills would be timelimited in order to induce consumption rather than saving. This was actually attempted – without helicopters – during the deflationary crisis in Japan. POP QUIZ 3.5.3: INFLATION AND DEFLATION 1. Explain how an economist would regard an increase in cigarette taxes in terms of inflation. 2. How might the functions of money be put out of order during inflation? 3. Why might you, the student, stand to lose due to inflation? 4. Using a supply and demand diagram for your home currency, explain why double-digit inflation will have a negative effect on your exchange rate – i.e. cause your currency to fall in value. 5. Why might deflation in fact be considered ‘good’ for an economy? 6. Outside the box question: Draw a demand curve for investment (investment schedule) showing how the quantity of investment is totally unaffected by a decrease in the interest rate below 0.5%. (Rory, please replace “malignant” with “malign.) CASE STUDY, DEFLATION; THE TEN YEAR SUNSET IN JAPAN The Land of The Rising Sun, Japan, was the env y of an astonished world during the 1960s,‘70s and ‘80s due to its f antastic growth rates and low inf lation and unemploy ment. GDP grew at an av erage of ov er 6% during the period 1960 to 1990 with unemploy ment rates hov ering around 2%. Y et during the beginning of the 1990s, Japan was to become a case study in the dif f iculties in getting out of malignant deflation . The background is to be f ound in the property price bubble of the late 1980s where property speculation and loose monetary policy led to alarming lev els of property prices. (For example, the classic story is that the land on which the Imperial Palace in Toky o stood was at one point v alued at more than the entire American state of Calif ornia!) When property prices started f alling in 1990 a goodly proportion of the loans taken by speculators could not be serv iced, and this created a sev ere lack of loanable f unds – which in turn had a negativ e ef f ect on inv estment. In spite of f alling interest rates, Japan has experienced f alling prices, e.g. def lation, and stagnant or f alling GDP during most of the period f rom 1995 to 2003. The Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, loosened monetary policy to the point where interest rates were v irtually zero during the period 1997 to 2003. This is explained by some – but def initely not all – economists as being a classic example ofliquidity the trap. When interest is zero and the economy continues to shrink, the Central Bank basically ‘runs out of ammunition ’ and there are f ew monetary policy tools lef t since it is impossible to lower interest rates and stimulate the economy . In addition, recall that real interest is nominal interest minus inf lation. Thus, nominal if interest is zero and inflation is below zero , there is anegative rate of real interest . The repercussions are as astounding as they are simple: • Negativ e real interest means that money increases in v alue ev en when y ou stick it in y our mattress (or f uton, in Japan). For example, Japan had inf lation of -1% (or def lation of 1%) during 2002 while nominal interest was zero. Thus sticking money in a f uton actually meant a real interest of 1% ov er a y ear. Negativ e real interest is theref ore a disincentiv e to spend money . • Monetary policy becomes inef f ectiv e since it is impossible to lower interest rates below zero – this would mean that banks would pay borrowers to take on debt! • Corporate and household debt rises when prices f all, since a f all in prices increases the negativ e real interest rate. This is a major disincentiv e to f irms and households in taking on debt to f und inv estment and consumption. In labour markets, f irms will need to increase productiv ity or cut wage costs in order to stay competitiv e, since f alling f inal prices mean that prof it margins are squeezed. In reality , f irms will not be able to lower wages and will resort to lay ing-of f workers. The reason is that when inf lation is 6% a f irm can accomplish real wage cuts of 4% by of f ering an increase of 2% nominal. To achiev e the same ef f ect when inf lation is zero the f irm would hav e to cut nominal wages by 4%! This is not practically f easible in most countries, wheref ore def lationary pressure inev itably leads to sizable lay of f s. Counter-inflationary policies There is no “cure all” for inflation and the policies applied will depend on the type of inflation and the costs government is willing to incur. The straightforward way to deal with inflation is to use demand-side policies (adjusting AD) for demand-pull inflation and supply-side policies (shifting AS) for cost-push inflation. Both have disadvantages, weaknesses and, as mentioned above, costs. Using contractionary demand-side policies to combat inflation entails implementing policies which decrease aggregate demand. Four key methods of dampening aggregate demand are: Increasing the rate of interest: this monetary policy lowers consumption and investment and thus decreases AD Decreasing the supply of money: another monetary policy – this increases interest rates…etc… Increasing taxes: the fiscal policy of higher income taxes will lower consumption, higher profit taxes will decrease investment and both have a contractionary effect on AD Decreasing government spending: the flip side of taxes, the fiscal policy of decreased government spending has a direct effect in lowering AD Figure 53.6 A shows how contractionary policies affect aggregate demand. Assuming general equilibrium at YNRU and the average price level indexed at 100, AD is increasing at a rate indicating AD1 and inflation of 5%. One or several contractionary policies are implement and AD settles instead at AD2, Y2 and an inflation rate of 3%. Figure 53.6 Inflation and demand-side and supply-side policies A: Decreasing AD Price level (index) B: Increasing AS Price level (index) LRAS LRAS SRAS1 SRAS2 SRAS 105 103 100 108 105 SRAS0 100 AD1 AD2 AD0 YNRU Y2 Y1 GDPreal/t AD0 Y1 Y2 YNRU GDPreal/t Using supply-side policies to lower cost-push inflation entails implementing policies which increase aggregate supply. Common examples of supply-side policies are: Lowering marginal income tax rates: higher net disposable incomes entices people to work more Labour market policy changes: legislation enabling easier hire rules for firms or decreasing minimum wage Incentives for capital formation: government can induce increased investment expenditure by giving firms tax breaks – e.g. allowing firms to deduct portions of investment spending from taxable profits Interventionist policies: government skills and re-training workshops can improve labour quality and also create better matches between labour supply and demand Figure 53.6 B illustrates how SRAS1 results in cost-push inflation of 8%. Over time – yes, this is a rather serious weakness – supply-side policies can shift SRAS back towards general equilibrium (SRAS1 to SRAS2) and a price level of 105 rather than 108. Evaluation of counter-inflationary policies This is a major issue and will be dealt with in greater depth in Sections 2.4 – 2.6. I limit the discussion here to the key points arising from the examples and diagrams used in Figure 53.6. 1) To start with, contractionary demand-side policies can be hugely unpopular with citizens and are basically not much of a crowd pleaser for politicians hoping to get re-elected. President Nixon was most reluctant to implement much-needed contractionary policies when inflation started rising in the late 1960s.7 2) Contractionary policies often lead to increased unemployment and lower incomes. 3) There is the very real risk that contractionary policies are too severe and that the result is recession. 4) Any policy used will be subject to time lags – it can take up to two years for the full effect of interest rate changes to feed through in an economy. Fiscal policies can take even longer. There is therefore a very real risk that the economy is already cooling down when the policies kick in, which could in fact worsen the economic downturn. 5) Supply-side policies avoid the issue of decreased incomes but are generally long term solutions and will not have any immediate effect on inflation. Instead the aim is more along the lines of allowing for long term growth while limiting inflationary pressure. 6) Lowering income tax rates can have serious repercussions on governments’ ability to balance the budget. (See Chapter 56.) 7) In reality the effect on the labour market of lower personal income tax cuts is very limited and simply does not increase labour supply. 7 See some fascinating economic history at Professor Bradford DeLongs site: http://econ161.berkeley.edu/econ_articles/theinflationofthes.html Summary and revision 1. Economics identifies three causes of inflation: a. Demand-pull inflation caused by increasing AD b. Cost-push inflation caused by decreasing AS c. Excess money supply leading to demand-pull inflation 2. The monetary transmission mechanism describes how a change in money supply “feeds through” to a change in AD. A ↓∆Sm → ↑∆r → ↓I → ↓AD. 3. Deflation is a general and consistent fall in the average price level. It is far more damaging to an economy than ‘reasonable’ inflation. There are two types of deflation: a. Benign deflation caused by increasing AS – there is deflation but rising GDPr b. Malign deflation caused by falling AD – prices and incomes both fall 4. Counter-inflationary policies are: a. Contractionary policies (e.g. policies aimed at decreasing AD) include raising interest rates, decreasing the supply of money, raising taxes on income and profits, decreasing government spending. b. Supply-side policies (increasing AS) include lowering marginal income tax rates, easing up on labour market regulations, privatisation of national industries, decreasing union power, increased education and skills in the work force…etc. 5. Demand-side contractionary policies have negative effects such as a decrease in government tax receipts, increased unemployment, lower GDP and personal income, time lags which make it difficult to time the policies correctly and the possibility of creating recession instead. 6. Supply-side policies have some serious weaknesses, such as actually increasing unemployment in the short run, can take a long time to implement and take effect, lower marginal tax rates can have serious consequences on the government budget, and studies show very limited effects of personal income tax cuts on labour supply.