* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

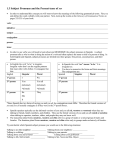

Download The Spanish Language Speed Learning Course - Figure B

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kagoshima verb conjugations wikipedia , lookup

Spanish verbs wikipedia , lookup

Hungarian verbs wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup