* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Earthquake Risk and Preparedness for Mining Consultants

Survey

Document related concepts

2009–18 Oklahoma earthquake swarms wikipedia , lookup

Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant wikipedia , lookup

1992 Cape Mendocino earthquakes wikipedia , lookup

Casualties of the 2010 Haiti earthquake wikipedia , lookup

1908 Messina earthquake wikipedia , lookup

Seismic retrofit wikipedia , lookup

2010 Canterbury earthquake wikipedia , lookup

2008 Sichuan earthquake wikipedia , lookup

2011 Christchurch earthquake wikipedia , lookup

Earthquake engineering wikipedia , lookup

1880 Luzon earthquakes wikipedia , lookup

1960 Valdivia earthquake wikipedia , lookup

Earthquake (1974 film) wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

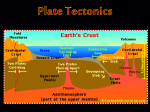

Earthquake Risk and Preparedness for Mining Consultants Lawrence Charlebois, Robertson GeoConsultants Inc., Vancouver, B.C., Canada Reinhard Zapata, Robertson GeoConsultants Inc., Vancouver, B.C., Canada See also accompanying presentation. Earthquake Risk and Mining For mining consultants, earthquake risk is a topic meriting serious discussion and planning – especially for those of us based in the Pacific Northwest, or anywhere along what we know as the Pacific Ring of Fire. Overlay a geologic map of tectonic plate boundaries, an earthquake risk map from your insurance firm, and a plot of metal mining operations across the globe and the correlation is clear – those of us involved with mining are exposed to earthquake risk regularly. The geologic forces that bring mineral wealth to the near-surface, also bring instability and volatility to otherwise serene, far-off places. Whether we’ve felt the ground roll, or not, is another matter – a function of years in the industry, frequent-flyer points, but mostly luck (or lack thereof). At a recent monthly safety meeting, our team addressed this topic head-on – studying seismic risk maps, debating best response actions (essentially the best way to protect your head from a crumbling building around you), even knocking on the paper-thin office walls to look for anchor points for our massive (and rather imposing) archive of textbooks, reports, and manuals arranged on unbalanced, seven-foot bookcases (dwarfing even our titanic geochemist). The text of this paper seeks to capture the ideas and recommendations generated hence. Whether at the office seeking refuge from the rain, enjoying the hum of the drill in a South American paradise, or enjoying the mountains and sea on the weekends, we should all seriously consider how a large seismic event could impact the way we live, work, and play. While the most gifted minds grapple with the issue of earthquake prediction, we can take concrete steps in preparing our work environments and homes - it is not a question of if, but when. Earthquake Risk in Vancouver A great number of mining consultants congregate in this city. The thrill of the mountains, the smell of the salted air, and the ghosts of miners-gone-by resonate strongly in Vancouver. The name-plates of junior mining companies line the hallways of concrete and glass high-rises (though the names change quite regularly). The big names in earth-science consulting are rooted here, much as the North Shore range is anchored in the rugged coastline. Lest we forget, the British Columbian coast has been violently rocked by earthquakes in the not-sodistant past. Large events in 1918, 1946, 1949, and as recently as 2011 should remind us of that convective soup of molten rock below the solid ground in which we drill, and dig, and make a living. Diligent structural engineers have updated their building codes over the years, but not all structures must meet these codes. There are exceptions for age and for occupancy, with lawyers, developers, shop owners, and the rest of us eager to save or make a dollar – for it is not cheap to live and eat in such a beautiful city. The many bridges radiating from the downtown are in various states of repair – some with freshly painted steel reinforcements, others with netting under the deck to catch the concrete as it spalls and looms over unsuspecting joggers and cyclists. 1 As a case study, we have taken our own office building, a nine-storey concrete frame structure with steel and glass façade, and applied a free online tool (www.hazardmapping.com) to assess the earthquake risk in our downtown workplace. We find that for the largest magnitude quake, there is risk of a handful of injuries and the possibility of one fatality. For smaller events, the number of injuries quickly drops off and no fatalities are expected. While a crude estimate based on a number of simplifications, this result shows the relative safety of our office building. The webpage cites braced steel high-rises as the most susceptible to damage and loss of life; several of these penetrate the skyline in the downtown business district. In our safety meeting, we watched fascinating video showing the magic of liquefaction and reviewed maps of Vancouver’s downtown and North Shore which show susceptibility to the phenomenon. Researchers from our own University of British Columbia have condemned the city and the buildings in it. Perhaps the risk is not as high as we are shown in the media, but risk there certainly is. Earthquake Risk at International Project Sites We note here only a few of our international project sites that have elevated risk of earthquakes, namely: • • • • Alaska, Chile, Peru, and Guatemala. There are more than what’s noted here, but these exemplify areas where miners and earthquakes meet. The evidence for this is recorded in the fault structures, deformed strata, intrusive bodies, cracked houses, and aboriginal stories that one encounters in the field. In just this past week, the USGS counts over 200 earthquakes along the Ring of Fire, where most of our mine sites lay. Earthquake Preparedness In the Office We submit that in the event of an earthquake, there may be very little time to react. Our senior engineers that have lived through earthquakes in California and South America tell us that it takes much time to digest what is happening under-foot in such an event. The best we can do is to have a plan that guides us how to react when we recognize an earthquake. In British Columbia, the course of action most widely supported is Drop, Cover, and Hold On! This assumes that one has both (i) a table/desk to crawl under, and (ii) time to do so. In other parts of the world, the “Golden Triangle” method is promoted. In this method, the idea is to get next to something large and stable so that debris falling from above is supported and does not crush you. The Golden Triangle assumes that (i) you have something large and stable close by, and (ii) small objects falling from height are not a hazard. It is apparent that neither approach is perfect in every scenario, but understanding the basic goal of each is important – wherever possible, protect your head and body from falling debris and try to anchor yourself near stable objects or structures. Generally, stay where you are and protect yourself. If it is 2 safe to move about the office, try to get to the central core of the building where it is generally strongest. Always avoid exterior walls and glass as they are particularly vulnerable during an earthquake. One of the most effective steps in preparing for an earthquake is to secure your physical work environment. Remove heavy objects from height around your workstation. Secure large bookcases, filing cabinets, and hutches to wall studs or floor joists – especially in hallways and near exits. Limit the amount of glass and breakables near your workstation. Ensure that framed pictures are secured in all corners to the wall, and avoid putting glass-framed pictures around you desk. Finally, be involved with your workplace emergency preparedness program. If your office has designated “floor wardens”, learn who they are and what their role is. Participate in emergency response drills at your workplace and make sure you have been shown where the emergency supplies (first-aid kits, flashlights, food rations, etc.) are stored. Learn the contents of the emergency response kits and speak with your employer about First-Aid certification. Remember that evacuation may not always be the safest choice; utility failures and falling debris may make ground-level evacuation hazardous. These precautions can, and should, be implemented at home, too. Formulate a response plan with your family, gather the necessary supplies, and make upgrades to your living space. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In the Field In the event of an earthquake occurring while you are working in the field, there are a few additional things to contemplate. • • • If you are in a location with limited access, how will transportation infrastructure have been affected (roadways, mountain passes, bridges, etc.)? If you are on an active mine site, how might utilities have been affected (pipelines, dewatering, ventilation, etc.)? Have major structures (tailings embankments, rock piles) been compromised? In the following text, we provide a few examples of common field scenarios and a recommended response approach for each. Driving/Commuting Whether commuting to and from the mine site, or navigating unmaintained roads to access remote wells at the toe of the tailings dam, driving is a necessary part of field work. Here is a recommended course of action, should you encounter an earthquake while driving. • • • Pull over and stop safely. Leave space for emergency vehicles to pass if possible. Avoid bridges, tunnels, overpasses, and utilities. Stay in the vehicle. The suspension may help dampen the ground movement and the roof will protect you from most falling debris. After the shaking has stopped, proceed with extreme caution. The landscape may have changed significantly and the roadways/passes may be damaged or obstructed. 3 • Be prepared for aftershocks. At the Drill Anyone in the field of geo-sciences is likely familiar with long days at the drill, looking for that one last piece of data to guide your design, or in an attempt to install that last monitoring well before the wet season arrives. Should you find yourself at a drill site during an earthquake, here are a few recommendations: • • • • Get away from the drill rig. Hit the emergency shut-off if you have time. The drill tower poses a serious threat under heavy shaking and could collapse. Keep at least the height of the tower away from the rig until the shaking has stopped and the rig has been inspected. Stay low to the ground. An earthquake may knock you off your feet, so staying low will reduce the severity of a fall. Be prepared for aftershocks. After the shaking stops, process to the pre-designated Emergency Meeting Point if safe. The EMP should be designated before the work starts as part of the site-specific safety plan. Underground Admittedly, our team spends limited time underground; however, as part of a field investigation, we may undertake monitoring of seeps from underground workings or other data collection activities. The emergency response plan at an underground mine is crucially important to understand if you are to be involved with any field activity. Keep in mind that for active underground mining operations, seismicity can be induced naturally and artificially (i.e. blasting-induced or due to changes in rock stresses during mining). Generally, one should always follow the mine-specific emergency plan. In larger mines, refuge stations are provided at specified intervals – know the locations of these stations. In Camp A mining camp is a second home for some, filled with hearty food, hard workers, and fond memories. In the event of an earthquake, one should protect themselves as they would at home or at the office. Be prepared for aftershocks and proceed to the Emergency Meeting Point if it is safe to do so. Away from Work – On the Weekends It’s true that we do not all work on weekends – at least not every weekend. The city of Vancouver is a tremendous place to indulge in every pleasure from shopping Vancouver’s Robson Street, to skiing at Cypress Mountain, to biking the Stanley Park seawall (and all within the same day if you’re up for it). While we cannot, and should not, be bothered with thinking of earthquake preparedness on the slopes or at the beach, we can take a few moments right now to identify the potential hazards resulting from a large earthquake in these settings. In public spaces, it is important to remain calm and try to avoid panicking crowds. Running masses of people leads to trampling, and that can result in serious injury and death. Also avoid smoking or lighting matches after a large event, as ruptured gas lines could present an explosion hazard. In the mountains, potential hazards include rock falls, mud flows, and avalanches. Seeking refuge in the tree line may provide some protection. 4 Near the ocean, it is recommended to move inland to higher ground. While the risk of tsunami in Vancouver is relatively low given our geography, the perfect combination of tide and earthquake location and strength could produce significant sea level rise following a major event. Closure Consultants working in the mining industry will be exposed to earthquake risk during their career. Living and working in the Pacific Northwest further increases our exposure to earthquake risk, but should not affect the quality of our lives. It is to everyone’s benefit to take simple action now to prepare for an earthquake at home, the office, and in the field. Having, understanding, challenging, and updating an emergency response plan at both a personal and organizational level are key aspects of earthquake preparedness. 5