* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Jigsaw Readings

Anoxic event wikipedia , lookup

Deep sea community wikipedia , lookup

History of geology wikipedia , lookup

Oceanic trench wikipedia , lookup

Tectonic–climatic interaction wikipedia , lookup

Abyssal plain wikipedia , lookup

Great Lakes tectonic zone wikipedia , lookup

Algoman orogeny wikipedia , lookup

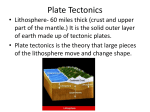

Using Science Notebooks to Develop Conceptual Understanding in Science: Jigsaw Readings 11 March 2011 NSTA National Conference San Francisco, CA BSCS 5415 Mark Dabling Blvd. Colorado Springs, CO 80918 [email protected] 719.531.5550 www.bscs.org Tectonic Setting 1: Crash—Colossal Collisions Collisions are dangerous, especially when you are in a car. In many car collisions, the car and an object come together too fast. The area where they meet has several characteristic shapes. Some of those shapes are shown in figure 13.10. What evidence do you see to indicate a collision? The collision of Earth’s tectonic plates is similar to car collisions. Of course, a tectonic collision is much slower and zones of collision can be thousands of kilometers long forming long chains of mountains over millions of years. But still, colliding tectonic plates result in distinct areas of uplift, just like the area on the car hood in figure 13.10. Sometimes the collision zones occur when two plates consisting of continental crust collide, or converge. These areas are called convergent zones (figure 13.11). There is only one place where this type of collision occurs today where the plate carrying India collided with the plate carrying Eurasia forming the highest mountains on Earth, the Himalayas. There is evidence that this type of collision has occurred at other times in Earth’s history resulting in ancient mountain ranges like the Appalachians in North America and the Ural Mountains of Russia. At other times, tectonic plates made of oceanic crust collide with continents. These are also convergent zones since plates are crashing together, but because oceanic crust is more dense than the continental crust, it is thrust downward, or subducted, beneath the continent (figure 13.11) forming subduction zones. The sinking oceanic crust is destroyed as it is pushed into the Earth’s mantle and the crustal material eventually melts. Several large tectonic features form where oceanic crust sinks into the mantle. Deep trenches on the ocean floor indicate where ocean crust is being subducted. Sometimes lines of volcanoes form above subduction zones. For example, a deep trench and line of volcanoes are found as the Juan de Fuca Plate is subducted beneath North America in the Pacific Northwest (figure 13.11). © BSCS Science: An Inquiry Approach, Level 2, p664-665, BSCS 2007. Page 1 Copyright © 2011 BSCS. All rights reserved. Tectonic Setting 2: Stretch—Breaking Up Is Hard to Do It’s not too hard to imagine tectonic plates crashing together. They’ve been doing that for millions of years! One possible result is that plates collide to form mountains chains. Another result is that one plate can be pushed into a subduction zone beneath the other. But what about the opposite result? What happens when plates move in opposite directions? What happens when plates are stretched to the limit? Just as when stretching chewing gum or rubber bands, stretching plates will eventually break and begin to rip apart. Geologists can observe this process happening today at many places on Earth. The point where plates have broken apart is called a rift. Rifts occurring in crustal plates under the continents often form long valleys, or rift valleys. These can be many thousands of feet deep. An example of a continental rift is the famous East African Rift, where a large fragment of continental Africa is being torn away to the east. A less well-known rift valley, the Rio Grande Rift, extends from northern Mexico to Colorado in the United States. Rift valleys are often associated with volcanic activity when hot molten rock emerges through cracks in the crust to reach the surface of the continent. Continental rifts can grow wider and wider with more stretching. They also can get deeper so that the land surface is below sea level. When these rift valleys meet the ocean, marine waters can submerge the floor of the rift valley. Modern examples of this are the Red Sea and the Gulf of California. The largest system of rifts on Earth is found beneath the oceans where tectonic plates are moving apart, or diverging. Therefore, rift zones are sometimes called divergent zones. The crust at oceanic divergent zones is so thin that volcanic activity – rising magma – occurs along nearly the entire length of the rift creating a an underwater mountain range, or ridge, rather than a valley. These ridges came to be called the mid-ocean ridges, because they were first linked to the ridge down the center of the Atlantic Ocean. However, not all divergent zones are in the middle of oceans, as the name might imply. A divergent zone in the South Pacific is much closer to South America than to Australia, and in the Pacific Northwest, the divergent zone along the Juan de Fuca Plate is quite close to the coast of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. Figure 13.9 shows the positions of the divergent zones associated with oceanic ridges. © BSCS Science: An Inquiry Approach, Level 2, p664-667, BSCS 2007. Page 2 Copyright © 2011 BSCS. All rights reserved. Tectonic Setting 3: Grind—Living on the Edge How do tectonic plates interact when they are not crashing together or pulling apart? Parking lots offer a clue. Have you ever seen a car try to squeeze through a space that is too small? The result could be a dramatic screeching and grinding as one car scrapes past the other. Tectonic plates do the same thing. The surface where the two plates grind past each other is called a transform fault. Perhaps the best-known transform fault between two plates is in the southwest part of North America. There, the San Andreas Fault marks where the Pacific Plate is grinding its way northwest along the edge of the North American Plate. A lurch along the San Andreas Fault caused the massive 1906 earthquake in San Francisco. This earthquake and the fires that resulted destroyed three-quarters of San Francisco and killed more than 3,000 people. Other devastating earthquakes have struck along the San Andreas Fault since 1906. A large earthquake in October 1989 hit the San Francisco Bay area in the middle of the World Series between the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland Athletics. The death toll was 65, with thousands injured and an estimated $8 billion of damage. Another example of a transform fault on a continent is the North Anatolian Fault in Turkey (figure 13.14). It also has a dangerous history of sudden movements and violent earthquakes with significant damage and deaths. Geologists used to think that transform faults were sharp zones of slip between rigid blocks. But modern technology provides evidence that this is only part of the story. For example, there is clearly a history of movement exactly on the San Andreas Fault. But recent sensors show that earthquakes and slippage occur across a wide region, not just on the fault line. So even though boundaries between tectonic plates may be shown on maps as distinct faults, in reality, transform faults can be broad zones of broken rock that are tens to hundreds of kilometers wide. Large earthquakes will likely occur throughout these unstable zones. Boundaries where plates pull apart are often called constructive plate boundaries because molten rock from deep in the Earth oozes out to form, or construct, new crust. Colliding plate boundaries are often called destructive plate boundaries, because crustal material is destroyed as it melts into magma or is converted into lofty mountain ranges. In contrast, transform plate boundaries are sometimes called conservative plate boundaries, because crustal material is neither created nor destroyed, but conserved. © BSCS Science: An Inquiry Approach, Level 2, pp. 668-669, BSCS 2007 Page 3 Copyright © 2011 BSCS. All rights reserved. The printed materials in this document that display © BSCS may be reproduced for use in workshops and other venues for the professional development of science educators. No materials contained in this document may be published, reproduced, or transmitted for commercial use without the written consent of BSCS. For permission and other rights under this copyright, please contact BSCS, 5415 Mark Dabling Blvd., Colorado Springs, CO 80918. Copyright © 2011 BSCS. All rights reserved.