* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Practical Framework for Syntactic Transfer of Compound

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Untranslatability wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

American Sign Language grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Basque verbs wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

A Practical Framework for Syntactic Transfer

of Compound-Complex Sentences

for English-Hindi Machine Translation

Durgesh Rao, Kavitha Mohanraj, Jayprasad Hegde, Vivek Mehta

and Parag Mahadane

National Centre for Software Technology,

Gulmohar Road 9, Juhu, Mumbai 400049, India.

Email: {durgesh,kavitham,jjhegde,vivekm,parag}@ncst.ernet.in

Abstract

In this paper, we present a practical framework for the syntactic transfer of compoundcomplex sentences from English to Hindi in the context of a transfer-based Machine Assisted

Translation (MAT) system. The analysis is based on the linguistic intuitions of the authors,

backed by evidence from a real-life corpus, and ongoing work on a building a practical MAT

system.

The description of the framework is based on a template-like representation. However, the

ideas expressed are essentially independent of the formalism or the representation. The most

important component of the framework is the mapping of finite as well as nonfinite verb

groups, in order to cover both simple as well as compound-complex sentences. Due to the

differences in style and structure between English and Hindi, this mapping is non-trivial. We

describe the major issues involved and suggest strategies for handling them.

1 Introduction

Machine translation (MT) from one natural language to another is widely accepted as a

challenging problem [Hutchins and Somers, 1992]. This becomes even more challenging

when the source and target languages are widely different in structure and style, as is the

case with English and Hindi. A very large number of issues and phenomena have to be dealt

with in translating between such a language pair.

In order to build a practical machine translation system for such a language pair, we need to

adopt a pragmatic approach. We need to combine our human linguistic intuitions about how

to solve these issues, with statistical evidence that helps us in prioritizing what issues are

the most important to solve first, thus combining the best of the so-called knowledge-based

and statistical approaches.

In this paper, we develop a practical framework for the syntactic transfer of compoundcomplex sentences from English to Hindi in the context of a transfer-based Machine Assisted

Translation (MAT) system. The analysis is based on the linguistic intuitions of the authors,

backed by evidence from a real-life corpus, and ongoing work on building a practical MAT

system.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, we mention the major differences

between English and Hindi. Next, we summarize the results and insights we have obtained

from an analysis of a parallel English-Hindi corpus that we have built. Based on these

insights, we then systematically build a framework for translating sentences in increasing

order of complexity. We conclude with a discussion of this framework in the light of our past

and ongoing work.

Examples of translations from English to Hindi are shown using the following formats: The

English source (E), the translated Hindi (H), the transliterated version of the Hindi in

Roman font (R) and an English gloss (G) of the Hindi.

2 Major Differences between English and Hindi

The major differences between English and Hindi can be divided into two broad categories:

structural differences and style differences.

The major structural

differences

between

English

[Quirk

et

[Allen, 1995] and Hindi [Sastri and Apte, 1968], [Bharati et al., 1995] are:

al.,

1985],

1. The basic sentence pattern is SVO in English, and SOV in Hindi.

Example:

E: “Rama(S) saw(V) Mohan(O)”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “rAma-ne(S) moHana-ko(O) deKA(V)”

2. English is a positional language, and is therefore (relatively) fixed-order. Relations

between various components of the sentence are shown mainly by the relative positions

of the components.

Example:

“Rama(S) killed(V) Ravana(O)”

is very different from

“Ravana(S) killed(V) Rama(O)”

Hindi is (relatively) free-order. Relations between various components of the sentence are

shown mainly by inflecting the components. Position changes of components normally

change the emphasis of an utterance, and not the basic meaning.

Example:

“rAma-ne(S) rAvaNa-ko(O) mArA(V)”

has the same meaning as

“rAvaNa-ko(O) rAma-ne(S) mArA(V)”

3. In English, the modifiers of an object can occur both before and after the object. For

example, adjectives usually precede nouns, whereas preposition phrases usually follow

nouns. In Hindi, modifiers usually occur before the object they modify.

Example:

E: “The first President of India”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “Barata-ke paHale rAXTrapati”

G: “India-of first president”

In addition, there are many minor differences. For example, English has three genders -masculine, feminine and neuter, whereas Hindi has only two -- masculine and feminine.

Hindi has determiners, but not articles such as a, an and the.

Apart from structural differences, there are a number of stylistic differences between English

and Hindi. We look at a few examples below. It is interesting to note that similar stylistic

differences occur between English and other Oriental languages such as Japanese [Tsutsumi,

1990].

1. Many transitive verbs in English map to intransitive verbs in Hindi.

Example:

“The Lok Sabha has 546 members”

should translate as

“In the Lok Sabha there are 546 members”

2. The pattern have followed by a special determiner like no, few, or little followed by a

noun is common in English, but not in Hindi.

Example:

“He has no children”

should translate as

“He does not have children”

Any framework for translating between English and Hindi would need to account for these

major differences. In addition, we would like the framework to have the following properties:

•

It should be as simple and intuitive as possible.

•

It should be flexible enough to support a fairly wide coverage of the source and target

languages to start with, and later be extended to cover more complex or rarely occurring

phenomena.

One important step in ensuring this is to work with a sample corpus representative of the

intended application domains. We can then get a clearer idea of the most important and

frequent phenomena that we need to address, and can separate them from problems that

may be theoretically very interesting, but have little practical relevance.

3 Parallel Corpus Analysis

In order to set our analysis on firm ground, we are working with a representative parallel

corpus in English and Hindi. This corpus consists of two parts:

•

•

The Annual Report parallel corpus: This contains the original English and the manually

translated Hindi version of one of the annual report of an organization.

The News Wire parallel corpus: This contains a few randomly selected English news

items from a news-wire and their manual Hindi translations.

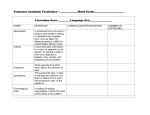

Table 1 contains the statistics about the size of this parallel corpus. A word in this corpus is a

white-space separated token as reported by the Unix wc utility. The sentence length is

measured in words.

English

Corpus

Annual Report

News Wire

Combined

Words

7532

4255

11787

Hindi

Avg. Sent.

Sentences

Words

Sentences

Length

450

16.74

8478

463

126

33.77

4679

123

576

13134

591

Table 1: Parallel corpus size statistics

Avg. Sent.

Length

18.26

36.55

-

This parallel corpus was tagged for Parts of Speech using the Brill tagger and the Penn

Treebank tagset [Brill, 1992]. The verb groups in both the corpora were identified and

manually verified. The number of finite and nonfinite verb groups per sentence was also

measured in both cases.

In English, a finite verb group has a tense, and usually contains an auxiliary verb. A

nonfinite verb group has no tense, and plays the role of a noun, adverb or adjective rather

than a verb. Also, the verb occurs in the to-infinitive, or the (past or present) participle form.

Similar rules apply for Hindi.

An important measure of the complexity of translation is the number of finite and nonfinite

verb groups that we need to translate. If F is the number of finite verb groups, and N is the

number of nonfinite verb groups in a sentence, we can classify sentences as:

•

•

•

Mono-finite: sentences with a single, finite verb group i.e. (F = 1, N = 0)

Multi-finite: sentences with more than one finite verb group and no nonfinite verb

group i.e. (F > 1, N = 0)

Compound-Complex: sentences with at least one finite and one nonfinite verb

group i.e. (F >= 1, N >= 1)

These are in increasing order of complexity of translation. Our aim is to cover all these three

types of sentences. It may be noted here that this classification is slightly different from the

traditional grammatical classification into simple, compound and complex. We use this

classification because it serves our purpose better in terms of mapping the clauses from

English to Hindi.

Table 2 displays the number of finite and nonfinite verb groups in the corpus, for every 100

sentences in English.

English

Hindi

Number of sentences

100

103

Finite verb groups

160

153

Nonfinite verb groups

78

69

Total verb groups

238

222

Table 2: Number of finite and nonfinite verb groups

for every 100 sentences in English

The following figure plots the cumulative percent frequency of finite and nonfinite verb

groups in English and Hindi against various values of F and N. For example, the fourth pair

Cumulative % Frequency

of bars (F=2, N=2) indicates that around 85 percent of sentences in both English and Hindi

are covered with upto 2 finite and 2 nonfinite verb groups.

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

N

F

0

1

0

2

3

0

1

2

4

0

2

1

1

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

4

4

No. of nonfinite(N) and finite(F) verb groups

eng%TotFreq

hindi%TotalFreq

Poly. (eng%TotFreq)

Poly. (hindi%TotalFreq)

Fig 1. Cumulative % Frequency vs Number of finite and nonfinite groups

Observations:

•

•

•

There is almost a one-to-one mapping between English and Hindi sentences (Table 2).

The ratio of finite to nonfinite is about 2:1, and is similar in English and Hindi. However,

there is a small tendency to move away from nonfinite verb groups in Hindi. We found

that this was normally done by either converting the nonfinite verbs into finite verbs, or

by nominalizing them (converting them into nouns).

More than 95 percent of the corpus is covered by sentences with less than 3 finite and 4

nonfinite verb groups.

These observations about human-translated corpora suggest that it is reasonable to do a

clause by clause translation when doing transfer-based machine translation from English to

Hindi. We have used this assumption in developing the framework below.

4 A Framework for English-Hindi Syntactic Transfer

Syntactic transfer deals with taking a structured representation of the source text and

mapping it to the structure that is appropriate for the target language. The input to this

process is the output of syntax analysis of the source text.

We now describe a framework for syntactic transfer from English to Hindi. Due to lack of

space, only a high-level outline is given, and the details have been skipped.

The core part of the framework deals with the transfer of a single clause, which is adequate

for handling mono-finite sentences. This is then used as the basis for extending the

framework to multi-finite and compound-complex sentences.

•

A clause is the basic unit of predication in any language. It consists of a single verb

group, which represents an action or event or state change. The verb group may consist

of one or more verbs, including auxiliaries and pre-modifying adverbs, and may be finite

or nonfinite. Every verb has certain sub-categorization features, which define the

number and nature of other constituents that attach with the verb to form the clause.

These features may be mandatory or optional.

The basic building block in our framework is called a slot. A slot has a name and a value. The

name is one of a predefined set, which indicates the slot type. A slot can have one or more

sub slots, thus allowing us to represent constituency (one part of a sentence being composed

of others). The value of a slot can be either a simple phrase, or another slot, thus allowing us

to represent recursion (a part of a sentence defined in terms of itself).

A clause can then be represented by a slot of type “Pivot”. Its value will be the verb group of

the clause. Its sub-slots will be the complements and adjuncts of the verb. We use the

following small set of slot types to represent the sub-slots of a pivot:

•

“Who/What” (for the syntactic subject)

•

“Whom/What” (for the syntactic object or indirect object)

•

“What” (for the syntactic direct object, when present)

•

“More-info” (for any other post-modifier)

We now look at how the above mechanisms are used to represent and translate various types

of clauses in increasing order of complexity.

4.1 Mapping Mono-Finite Sentences

A mono-finite sentence consists of a single Pivot slot containing the verb group, and one or

more sub-slots as defined by the mandatory and optional complements of the verb group.

Let us introduce the following notation:

S: Subject (the value of the Who/What slot)

O: Object (the value of the Whom/What slot)

V: Verb group (the value of the Pivot slot under consideration)

Further, let

Sm: Subject post-modifiers (the sub-slots of S, if any, in order)

Om: Object post-modifiers (the sub-slots of O, if any, in order)

Vm: Verb post-modifiers (the expected sub-slots of the verb, if any, in order)

Cm: Clause post-modifiers (the optional sub-slots of the verb, if any, in order)

Then, the basic mapping rule for English-Hindi transfer of a clause is:

S Sm V Vm O Om Cm è Cm' Sm' S' Om' O' Vm' V'

where x' represents the Hindi translation of x. If x has any post-modifiers, they will go

before x' in the translation, recursively.

Let us illustrate this with an example. Consider the English sentence

E: "The President of America will visit the capital of Rajasthan in the month of December"

This would be represented in our framework as:

Pivot: will visit

Who/What: The President

More-info: of America

Whom/What: the capital

(O)

More-info: of Rajasthan (Om)

More-info: in the month

(Cm)

More-info: of December

(V)

(S)

(Sm)

Applying the transfer rule, this would be translated as:

H: “? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ”?

R:

"disaMbara-ke

maHIne-meM

amarIkA-ke

rAXTrapati

rAjasthAna-kI

rAjadhAnI-kI sEra kareMge"

G: “December-of month-in America-of President Rajasthan-of capital-of tour will-do”

There are several issues related to the generation of Hindi to translate the individual subslots. As Hindi is a highly inflectional language, the various constituents need to be

appropriately inflected using the information derived from the English representation.

The strategies used for these have been described in detail in an earlier work [Rao et al,

1998]. Therefore, only the main points are summarized here:

•

The Hindi inflection of the verb group mapping is a fairly complex function of the tense,

aspect, voice and modality of the verb group. It also depends on the gender, number and

person of its agreement target. The agreement target which in turn depends on various

factors such as the transitivity and the tense of the verb group. We have captured these

rules into the lexical transfer component.

•

The Hindi noun groups need to be inflected to reflect case information. The mapping

from English prepositions to Hindi postpositional inflections is highly complex. We have

used a rule-based system that uses syntacto-semantic information about the context in

which a preposition occurs, to map the preposition into the appropriate inflection marker.

A prototype using the above strategy has been implemented and described in [Rao et al,

1998].

4.2 Mapping Multi-Finite Sentences

A multi-finite sentence consists of two or more finite clauses connected by a coordinating

conjunction such as "and". To handle such sentences, we need to extend our framework by

adding a pivot type called Operator, which represents the conjunction, and takes the

appropriate number of pivot slots as sub-slots, and has a mapping rule specific to each

operator template.

For example, the simple rule for "and" sentences would be:

S1 “and” S2 è S1' “Ora” S2'

where

S1' and S2' are the Hindi translations of S1 and S2,

and “Ora” is the Hindi translation of "and".

A slightly more complicated rule is needed for “if-then” sentences:

“If” S1 (“then”) S2 è “agara” S1’ (“to”) S2’.

In this case, the verb group in S1’ should take the conditional tense (also known as the

doubtful tense) in Hindi.

Sentential complements (with an implicit or explicit “that”) have the simple rule

S1 (“that”) S2 è S1 “ki” S2

with an important exception, as discussed below.

In case of indirect reported speech (which is the norm in a news corpus), the reported

sentence takes the past tense in English due to agreement with the reporting main verb

(such as “told” or “said”). However, formal Hindi has no indirect reported speech, and hence

the actual tense information needs to be recovered and used, which may not be easy.

Consider the following:

E: “The minister said that the prices had fallen”

is ambiguous in Hindi between

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “maMtrI ne kaHA ki kImateM girIM HEM”

(The minister said, “The prices have fallen”)

and

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “maMtrI ne kaHA ki kImateM girIM thIM”

(The minister said, “The prices had fallen”)

while

E: “The minister said that the prices had fallen last year”

is not, since it clearly indicates the latter meaning due to the time reference.

4.3 Mapping Compound-Complex Sentences

A compound-complex sentence consists of at least one finite and one nonfinite verb group.

The compound clauses of the sentence can be mapped using the strategy described for multifinite sentences above. Each finite verb group can be mapped using the strategy described for

mono-finite sentences above. That leaves the inflection of the nonfinite verb groups to be

handled.

Nonfinite verb groups are of three main types:

• To-infinitive

• –ING participle

• –ED participle

4.3.1 To-infinitive

In many cases, a to-infinitive clause plays the role of a noun phrase. In such a case, the

clause can be mapped using the same rule as for the mono-finite clause, except that the

inflection in Hindi will be the non-tensed “nA” ending which denotes nominalization.

Example:

E: “He wants to go home”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “vaHa Gara jAnA cAHatA HE”

G: “He home to-go wants”

However, in other cases, the to-infinitive clause does not play the role of a noun phrase, and

so it behaves more like a verb group. The following common cases arise:

a) The to-infinitive clause has a subject.

Example:

E: “I want you to buy me a house”

è E: “I want that you should buy me a house”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “mEM cAhatA hUM ki tum mere liye Gara kharIdo”

G: “I want-am that you me-for house buy”

This case is handled by treating the to-infinitive clause like a complete sentence

introduced with a “that”, and adding a conditional verb inflection.

b) The verb group in the main clause is copular (is based on the root “be”).

Example:

E: “We were happy to see him”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “HameM use deKakara KuSI huI”

G: “us-for him-to see-{because/after} happiness became”

Here the to-infinitive verb group in Hindi is inflected with a “kara” ending to indicate a

causality and/or sequentiality between the nonfinite verb and the main verb.

4.3.2 –ING participle

The –ING participle clause mainly occurs in the following contexts, in decreasing order of

frequency in our corpora:

a. As a pre-modifying adverbial to the main verb.

Example:

E: “Addressing a news conference, the minister said …”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

...

R: “saMvAdadAtA sammelana ko sambodhita karate hue maMtrIjI ne kaHA ki …”

G: “News conference-to addressed-doing-while minister said that..”

Here the –ING participle verb group in Hindi is inflected with a “te Hue” ending to indicate a

co-occurrence between the two verbs, and then placed in front of the main clause which it is

modifying.

b. As a post-modifying adverbial to the main verb.

Example:

E: “The terrorists attacked the village, gunning down five people”

(Note the comma between the –ING clause and the preceding noun, which prevents this

clause from being confused with a relative adjective clause to the noun.)

This is usually a more stylized (and typically journalistic) way of saying

E: “The terrorists attacked the village, AND gunned down five people”.

It is best translated in Hindi as the latter, after borrowing the tense from the main verb

group into the –ING verb group (in this case, the simple past tense).

c. As a relative adjective clause to a noun group.

Example:

E: “The boy sitting on the tree is my brother”.

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “peDa-para bETA laDakA merA BAI HE”.

G: “Tree-on seated boy my brother is”

Here the –ING participle clause is inflected in Hindi to reflect the gender-number-person

information of the noun group it is modifying, and then placed before the noun, just like a

simple adjective would be.

4.3.2 –ED participle

The –ED participle clause mainly occurs in the following contexts, in decreasing order of

frequency in our corpora:

a. As a relative adjective clause to a noun group.

Example:

E: “The issues raised in this paper are very interesting”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “isa leKA-meM uThAe-gae mudde baDe dilacaspa HEM”

G: “This paper-in raise-done issues very interesting are”

Here the –ED participle clause is inflected in Hindi to reflect the gender-number-person

information of the noun group it is modifying, as well as a passive marker, and then placed

before the noun, just like a simple adjective would be.

However, in many cases where there exists a Hindi adjective with the same form as the past

participle, it is more appropriate to use the adjective, rather than the verb group.

Example:

E: “The papers received for this conference are very interesting”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “isa sammelana-ke-liye prApta leKa baDe dilacaspa HEM”

G: “This conference-for obtained{adj} papers very interesting are”

b. As an adverbial modifying the main verb. This may either be a pre-modifier as in the first

example below, or a post-modifier, set off from any preceding noun by a comma, as in the

second example, just like a simple adverb would be.

Example:

E: “Tired of the daily fighting, the people are looking for peace”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “roja-kI laDAI-se thakakara loga SAMti-kI talASa-meM HEM”

G: “Daily-of fighting-from tired-{because/after} people peace-of search-in are”

Example:

E: “He sat on the ground, tired after the long trip”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “laMbI sEra-ke-bAda thakakara vaHA jamIna-para bEThA”

G: “Long trip-after tired-{because/after} he ground-on sat”

In both cases, the -ED participle verb group in Hindi is inflected with a “kara” ending to

indicate a sequentiality or causality between itself and the main verb, and is placed in front

of the main clause.

4.4 Idioms and Phrasal Verbs

Idioms and phrasal verbs need to be explicitly stored and handled.

Example:

E: “This goes to show that we were right in the first place”

H: ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

R: “yaHa sAbita karatA-HE ki Hama paHale-se HI saHI the”

G: “This proved{adj} does that we earlier-from {emph} right were”.

Here, “goes to show” and “in the first place” need to be stored in the lexicon as a phrasal verb

and adverb respectively (using appropriate mechanisms to allow them to have modifiers).

5 Discussion

The framework presented above has been informally analyzed and found to be adequate to

handle the range of sentences encountered in the parallel corpus. It has been implemented

for mono-finite sentences, and is being extended to cover multi-finite and compound-complex

sentences. Once this is done, it would be possible to make a firmer statement about the

completeness and correctness of the framework.

Note that we have handled only declarative sentences, since our application and corpus are

dominated by them. We believe it should be fairly easy to extend the framework to cover

interrogative and imperative sentences as well.

Since the scope of this paper is limited to issues of syntactic transfer between English and

Hindi, we have not touched upon other issues related to machine translation, for example,

the issue of handling ambiguities during analysis and generation. A complete translation

system would obviously need to handle these issues too.

6 Conclusion

Though English, and to a lesser degree Hindi, have been extensively studied individually,

there is not much accessible literature on translation between the two, particularly in the

context of transfer-based Machine Translation. We have made an attempt to start filling this

gap through this paper -- we have presented a practical framework for the syntactic transfer

of compound-complex sentences from English to Hindi in the context of a transfer-based

Machine Assisted Translation (MAT) system.

The most important component of the framework is the mapping of finite as well as nonfinite

verb groups, in order to cover both simple as well as compound-complex sentences. Due to

the differences in style and structure between English and Hindi, this mapping is non-trivial.

We have described the major issues involved and suggested strategies for handling them.

We believe our framework to be fairly intuitive, and hence easy to implement and maintain

without needing very elaborate linguistic knowledge. This is an important practical

consideration in building a real-life MT system. We have not seriously attempted to address

issues of pragmatics and style in this framework. That would be one of the main areas to

explore in future.

Acknowledgements

The ideas presented in this document include the work of not just the authors, but many

former colleagues as well. The authors would like to acknowledge some of them: Dr Ramani,

former Director, NCST, Dr R Chandrasekar, Radhika Mamidi, Dhawal Bhagwat, Puneet

Srivastava and Prince Tinna. We would also like to thank our colleagues from the KBCS,

Graphics and SPC divisions at NCST.

References

[Allen, 1995]

James Allen. Natural Language Understanding, 2 ed. Benjamin Cummings, 1995.

[Bharati et al, 1995]

Bharati A, Chaitanya V and Sangal R. Natural Language Processing: A Paninian

Perspective. Prentice Hall of India, 1995.

[Brill, 1992]

Brill E. A simple rule-based part of speech tagger. In Proceedings of the Third Conference on

Applied Natural Language Processing, Trento, Italy, 1992. ACL.

[Hutchins and Somers, 1992]

Hutchins W and Somers H. An Introduction to Machine Translation. Academic Press, 1992.

[Quirk et al, 1985]

Quirk R, Greenbaum S, Leech G and Svartvik J. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English

Language. Longman Inc., 1985.

[Rao et al, 1998]

Rao D, Bhattacharya P and Mamidi R. Natural Language Generation for English to Hindi

Human-Aided Machine Translation. In Sasikumar M, Rao D, Raviprakash P, Ramani S (Ed).

Proceedings of the “Knowledge Based Computer Systems International Conference, 1998”,

KBCS-98, National Centre for Software Technology, Mumbai, 1998.

[Sastri and Apte, 1968]

Sastri SR and Apte B. Hindi Grammar. Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha, Madras,

India, 1968.