* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Livy: The History Of Rome

Survey

Document related concepts

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

First secessio plebis wikipedia , lookup

Leges regiae wikipedia , lookup

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

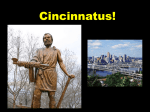

1 Livy: The History Of Rome The Death of Romulus After Romulus had ruled for many years and had many successes, he became tyrannical. The story goes that there was a meeting of the Senate on the Campus Martius [Field of Mars] outside the city. During the meeting a violent thunderstorm swept the field. When the storm cleared, Romulus was nowhere to be seen, and it was assumed that he had been taken to heaven by Jupiter the Thunderer; that was the word given out by the Senators. However, it is commonly thought that Romulus was actually murdered by the Senators who cut up his body, each one smuggling out a portion under his robes. The Rape of Lucretia Back in Rome, they found vigorous preparations under way for a war with the Rutuli; they were a people of great wealth, and this was the reason for the war. Tarquin [King of Rome] needed to replenish his treasury because of the great expenses that his public building program had caused. In addition, the plebeians had become unhappy, not only because of Tarquin’s generally tyrannical nature, but also because of the manual labor they had been forced to do at the king’s bidding—labor more properly belonging to slaves. The distribution of plunder from a captured town would go a long way to soften their resentment. The attempt was made to take Ardea, the richest Rutulian town, by assault; it failed and siege operations were begun. The army settled down into permanent quarters. With little prospect for action, the war looked like it would take a long time. Under these circumstances, frequent leaves were granted, especially to the officers. Indeed, the young princes spent most of their time in lavish entertainments. They were drinking one day in the tent of Sextus Tarquin [Son of Tarquin] when someone chanced to mention the subject of wives. Each of them extravagantly praised his own wife, and the rivalry got hotter and hotter. Finally Collatinus cried, “Stop! What need is there of words, when in a few hours we can prove beyond doubt the superiority of my wife Lucretia? Why should we not ride to Rome and see with our own eyes what kind of women our wives are? There is no better evidence than what a man sees when he comes home unexpectedly.” They had all drunk a good deal, and the proposal appealed to them, so they mounted their horses and galloped off to Rome. They reached the city as dusk was falling; there the wives of the royal princes were found enjoying themselves with a group of young friends at a luxurious dinner party. The riders went on to the house of Collatinus where they found Lucretia very differently employed: it was already late at night, but she was still hard at work at her spinning. Which wife had won the contest of womanly virtue was no longer in doubt. With all courtesy, Lucretia rose to bid her husband and the princes welcome, and Collatinus, pleased with his success, invited everyone to stay and eat. It was at that fatal supper that Lucretia’s beauty and virtue kindled in Sextus Tarquin the flame of lust. 2 Nothing further happened that night; the little jaunt was over, and the three men rode back to camp. A few days later Sextus rode back to Collatinus’ house where he was hospitably welcomed by Lucretia. After supper he was escorted, like the honored visitor he was thought to be, to the guest chamber. He waited until everyone was asleep; and, when all was quiet, he drew his sword and made his way to Lucretia’s room, determined to rape her. She was asleep. Laying his left hand on her breast, “Lucretia,” he whispered, “not a sound. I am Sextus Tarquin. I am armed. If you utter a word, I will kill you.” Lucretia opened her eyes in terror; death was near, and no help was at hand. Sextus urged his love, begged, threatened, pleaded with her to submit. But in vain, not even the threat of death could bend her will. “If death will not move you,” Sextus cried, “dishonor will. I will kill you first, and then slit the throat of a slave and lay him by your side. Will everyone not believe that you have been caught in adultery with a slave—and paid the price?” Even the most resolute chastity could not stand against such a threat. Lucretia yielded, Sextus enjoyed her, and then rode away, proud of his success. The unhappy girl wrote to her father in Rome and her husband in Ardea, urging them both to come at once with a trusted friend, for a terrible thing had happened. Her father came with Valerius and her husband with Brutus. They found Lucretia sitting in her room in deep distress. Tears rose to her eyes as they entered, and to her husband’s question, “Is all well with you?” she answered, “No. What can be well with a woman who has lost her honor? In your bed, Collatinus, is the impress of another man. My body only has been violated; my heart is innocent, and death will be my witness. Give me your promise that the rapist will be punished—he is Sextus Tarquin. He came last night as my enemy disguised as my guest, and took his pleasure of me. That pleasure will be my death—and his too if you are men.” The promise was given. One after another they tried to comfort her. They told her she was helpless and shared no guilt; Tarquin alone had committed the crime. It was the mind that sinned, not the body: without intention there could never be guilt. “What is due to him,” Lucretia said, “is for you to decide. As for me I am innocent of fault, but I will take my punishment. I shall never provide a precedent for adulterous women to escape what they deserve.” With these words she drew a knife from under her robe; and driving it into her heart, fell forward, dead. The Sacrifice of Gaius Mucius Thwarted in his attempt to take the city by assault, Porsena now turned to siege operations. He soon had the city effectively blockaded; and although the Romans conducted some successful raids and ambushes, the siege nonetheless continued. Porsena’s hopes rose of being able to starve the city into submission. It was in this situation that the young aristocrat Gaius Mucius performed his famous act of heroism. In the days of the monarchy Rome had never suffered a siege, and now they were put into in this humiliating position by the very people, the Etruscans, who they had just expelled in winning their liberty. His first thought was to make his way, on his own, 3 through the enemy lines; but there was a risk, if he did this without telling anyone and was captured, he would be considered a deserter. Accordingly, he changed his mind and presented himself to the Senate. The Senate gave their approval for Mucius to proceed. He arrived at the Etruscan camp with a dagger concealed in his clothing. He took his stand at the side of a raised platform on which the king was sitting. A great many people were present as it was pay day for the army. By the side of Porsena sat his secretary; this man was dressed very much like the king. Fearing to ask questions and be exposed as a stranger, Mucius took a chance—and stabbed the secretary. There was a cry of alarm, and Mucius was seized and brought before the king. There was no help, and his situation was desperate, but Mucius never flinched, and when he spoke, his words were those of a man who inspires fear but feels none. “I am a Roman,” he said to the king, “my name is Gaius Mucius, and I came here to kill you, my enemy. I have as much courage to die as to kill; it is our Roman way to do and suffer bravely. Nor am I alone in my plan to kill you; behind me is a long line of men eager for the same honor. Gird yourself, if you will, for the struggle—a struggle for your life from hour to hour, with an armed enemy always at your door. That is the war we declare on you: you need fear no action on the field, army against army; this war will be fought against you alone by one of us at a time.” Porsena, alarmed and enraged, ordered the prisoner to be burned alive unless he at once divulged the plot he hinted at. Then Mucius cried, “See how cheap men hold their bodies when they care only for honor,” as he thrust his right hand into the fire which had been prepared for a sacrifice; he let it burn there as if he were unconscious of pain. Porsena was so astonished at this display that he ordered Mucius dragged from the fire and said, “Go free. You have dared to be a worse enemy to yourself than me. I would bless your courage if you came from my country; but as an honorable enemy, I grant you pardon, life, and liberty.” “Since you respect courage,” Mucius replied, “I will tell you in gratitude what you could not force from me with threats. There are three hundred of us in Rome, all young and of noble blood like myself, who have sworn an attempt on your life in this fashion. It was I who drew the first lot; the rest will follow until one of us gets you.” The release of Mucius (who was afterward known as Scaevola, ‘The Left-Handed Man’) was quickly followed in Rome by envoys from Porsena. The prospect of having to face the same thing again had so shaken the king that he came with proposals of peace. One of the demands was for the return of the Tarquins. Porsena knew that it would be refused—as it was—but he felt that he had to include it for honor’s sake. He did succeed in getting the Romans to return some conquered territory to Veii, and to give hostages for the evacuation of the Janiculum. Peace was made on those terms: Porsena evacuated his troops from the Janiculum and withdrew from Roman territory. Gaius Mucius was rewarded by the Senate with a grant of land, subsequently known as the Mucian meadow. 4 Horatius at the Bridge The Tarquins finally took refuge at the Etruscan city of Clusium, ruled by Lars Porsena. Lars Porsena felt that his own security would be increased by restoring monarchy in Rome, and also felt that Etruscan prestige would be enhanced if the king were of Etruscan blood. Convinced by these arguments, Lars Porsena lost no time in invading Roman territory. On the approach of the Etruscan army, the people all moved into the city. The most vulnerable point was the wooden bridge over the Tiber, and the Etruscans would have crossed it had it not been for the courage of one man, Horatius Cocles—that great soldier who Rome’s fortune provided for her as a shield on that day of peril. Horatius was on guard at the bridge when the Janiculum hill was captured by a sudden attack. The enemy forces came pouring down the hill, while the Roman troops were throwing away their weapons and running, behaving more like an undisciplined mob than an army. Horatius acted promptly; he stopped as many of his fleeing comrades as he could and shouted, “By the gods! Don’t you see that running does you no good? If you leave the bridge open behind you, you will soon have more Etruscans on the Capitol and Palatine than you left on the Janiculum.” He urged them with all his power to destroy the bridge by any means they could, and he offered to hold up the Etruscan advance by himself. Proudly he took his stand at the outer end of the bridge, sword in hand and ready for action, one man against an army. The advancing Etruscans paused in sheer amazement at such reckless courage. Two other aristocrats, Spurius Lartius and Titus Herminius, were ashamed to leave Horatius alone, and with their support he survived the first critical minutes of danger. Soon, however, he forced them to save themselves and leave him, for little was now left of the bridge, and the demolition squads were calling them back before the bridge collapsed. Once more Horatius stood alone; he challenged one after another to single combat, calling them slaves who had come themselves to rob another of liberty. For a while they hung back, each man waiting for his neighbor to make the first move, but finally with a fierce cry they hurled their spears at him. Horatius caught the spears on his shield and resolutely straddled the bridge, holding his ground. The Etruscans moved forward and would have pushed him aside by sheer weight of numbers, but their advance was checked by the falling of the bridge and the cheer this brought from the Romans. The Etruscans could only watch as Horatius, with a prayer to father Tiber, plunged into the water and swam safely to the other side even though missiles fell all around him. Cincinnatus as Dictator The Aequi had attacked Roman territories. Nothing could have been more unexpected; Rome was thrown into a state of alarm just as if the city itself were under attack. The situation clearly called for a dictator; and with no dissent Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus was named to the post. He was at that moment working a little three acre farm west of the Tiber, just opposite the spot where the shipyards are today. The envoys from the city found him at 5 work on his land—digging a ditch, perhaps, or plowing. Greetings were exchanged, and he was asked to put on his toga to hear the Senate’s instructions. This naturally surprised him, and he asked his wife to run to their cottage and bring it. The toga was brought, and wiping the grimy sweat from his hands and face, he put it on. At once the envoys saluted him as dictator, invited him to enter Rome, and informed him of the danger to Minucius’ army. A state boat was waiting for him on the river, and at the city he was welcomed by his three sons, then by other kinsmen and friends, and then by the entire Senate. Accompanied by his lictors, he was escorted to his house. The next day, after a quiet night, the dictator was in the forum at dawn. Here were his instructions: legal business was to be suspended, all shops were to be closed, no private business could be transacted, all men of military age were to parade with their equipment on the Campus Martius before sunset. Each man was to bring five days ration of bread and twelve stakes. All men over military age were to prepare food while the younger men got their equipment together. At midnight the army halted not far from the enemy; Cincinnatus scouted the Aequian position and then ordered his men to leave their baggage and return with just their weapons and stakes. He then marched them to form a complete ring around the enemy. Their orders were to raise a war cry and then dig, each were they stood, until they had a staked trench and palisade around the Aequi. The Roman shout informed the enemy that they were surrounded, and told the besieged Romans that help had arrived. At this moment, Cincinnatus attacked; the Aequi were caught between and soon gave up the struggle and begged the Romans not to complete the slaughter, but to disarm them and let them go with their lives. This Cincinnatus did, but on humiliating terms. Their commander, Gracchus, and other leading men were to be surrendered in chains; the town of Corbio was to be evacuated; the Aequian soldiers were let go, but forced to pass under a yoke. A yoke was made of three spears, two fixed upright and a third tied across them; the Aequian army was made to pass under it. The Aequians had been stripped before their release; and their camp, with all its valuable property was captured. In the Senate a decree was passed inviting Cincinnatus to enter the city in triumph with his troops. The chariot that he rode in was preceded by the captured enemy commanders; he was followed by his army carrying the rich spoils. They say that not a house in Rome was without a table spread for the entertainment of the troops. Only some pending legal business prevented Cincinnatus from resigning his dictatorship immediately; he finally resigned after fifteen days, having originally accepted the office for six months.