* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

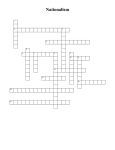

Download Nationalism and Internationalism in the Era of the Civil War

Texas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Confederate States of America wikipedia , lookup

Blockade runners of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

Hampton Roads Conference wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Economy of the Confederate States of America wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Lost Cause of the Confederacy wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Confederate privateer wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup