* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Abraham Lincoln and Greensburg, Indiana

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Gettysburg Address wikipedia , lookup

Baltimore riot of 1861 wikipedia , lookup

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Hampton Roads Conference wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

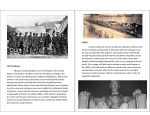

“A STRONG ARDENT AND SENTIMENT IN FAVOR OF ” LIBERTY Abraham Lincoln and Greensburg, Indiana CALVIN D. DAVIS 36 Interior.indd 36 TR ACE S Winter 2012 2/7/12 2:40 PM A new Honda factory in Greensburg, Indiana, the county seat of Decatur County, has attracted wide attention in the state and in the community. Whenever a train loaded with new automobiles leaves the Honda plant, local citizens regard the event as a welcome relief from reports of job cuts at area factories. The attention harkens back to a time when the community buzzed with anticipation about whistlestop visits by an up-and-coming politician, Abraham Lincoln. A local Main Street organization is planning a monument commemorating Lincoln’s visits on September 19, 1859, and February 12, 1861. The monument brings to mind a period during which citizens of Decatur County and its county seat had important roles in the politics that preceded the Civil War and in the war itself. When U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, on January 23, 1854, introduced a bill to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska he set in motion plans for a transcontinental railroad. Unfortunately his proposal also began a political storm that culminated in the Civil War. Dissatisfaction about the Compromise of 1850 and the KansasNebraska Act led to drastic changes in the nation’s political parties. The Whig Party began to fall apart during the 1852 presidential election, and the Democrats had serious divisions after the KansasNebraska Act passed. A meeting of Whigs, Democrats, and Free-Soilers in Ripon, Wisconsin, on February 28, 1854, called for a new party to demand exclusion of slavery from the territories and urged that the party be called Republican. A meeting at Jackson, Michigan, on July 6, 1854, adopted that name. Actually, the Republican Party was created by meetings in many Above: A lithograph depicting Abraham Lincoln returning to his Springfield, Illinois, home after winning the presidency in 1860. The return home is fictional, as Lincoln did not leave to campaign for the White House. The same picture was used as a scene of Lincoln returning home after his debates with U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas. TR ACE S Interior.indd 37 Winter 2012 37 2/7/12 2:40 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG communities in the North. One such meeting was a convention of Washington Township’s Democrats in Greensburg on June 9, 1854. The convention passed a resolution declaring: “That we as Democrats stand politically as we did in 1849, in opposition to the further extension of Slavery and do now believe as we did then, that Congress should prohibit it in all the territories and further, that we will vote for no man for congress who will not endorse this sentiment, and pledge himself by his vote and influence to carry out the same when elected.” While some men at that meeting remained Democrats, others began working with former Whigs to organize a new party. Although an exact date cannot be ascertained for when the Republican Party came into existence in Decatur County, a young lawyer who was present at the Greensburg convention, Will Cumback, was elected to Congress from the Fourth District later that year as an anti-KansasNebraska Act candidate. In Congress he attracted attention by his part in a prolonged struggle that ended with the election of an antislavery congressman from Massachusetts, Nathaniel Banks, as speaker of the House of Representatives. Cumback became one of the vigorous opponents of slavery in the House. Unanimously renominated in 1856 he was, nonetheless, defeated by Democrat James B. Foley of Greensburg. In spite of his defeat, Cumback remained an influential Republican leader in Decatur County and in the Fourth Congressional District. Much happened in 1856 and 1857 to keep attention on the nation’s western territories. In Kansas there was virtual civil war. Speaking at his inauguration as the nation’s fifteenth president on March 4, 1857, Democrat James Buchanan said that the question of slavery in the territories was really one the Supreme Court should decide. Buchanan’s views seemed in accord with Douglas’s support of popular sovereignty, but when the Supreme Court two days later announced its decision in Above: An 1856 cartoon places blame on Democrats for violence perpetrated against antislavery settlers in Kansas in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Here a bearded “freesoiler” has been bound to the “Democratic Platform” and is restrained by James Buchanan and Lewis Cass. Douglas and President Franklin Pierce, also shown as tiny figures, force a black man into the giant’s gaping mouth. Opposite: A Harper’s Weekly drawing of Lincoln comparing his height with another man on his way to assume the presidency in 1860. 38 Interior.indd 38 TR ACE S the famous Dred Scott case, such a position became seriously limited—if not made impossible. The Court ruled that the Missouri Compromise had been unconstitutional. Thereafter it was not possible to restore the compromise by legislation, and very little room was left for letting inhabitants of a territory determine whether the territory should be slave or free. Southern leaders applauded; Douglas was appalled. A split between northern and southern Democrats began that finally divided their party. In 1858 Douglas campaigned for another term as an Illinois senator. While the state legislature actually elected senators, there was a popular advisory vote. Douglas began speaking in many communities; when the Republican candidate, Lincoln, suggested a series of debates, Douglas accepted. Beginning at Ottawa, Illinois, on August 2, and concluding at Alton, Illinois, on October 15, Lincoln and Douglas debated seven times. The most important debate was at Freeport, Illinois, on August 27. Lincoln asked Douglas how, despite the Dred Scott decision, he could continue to urge that popular sovereignty determine whether a territory would be slave or free. Douglas replied that “police regulations” were necessary if slavery was to exist. Only a legislature could enact such regulations, but there was no power that could compel it to do so. Douglas’s new doctrine satisfied many northern Democrats, but not their counterparts in the South. They insisted that the Dred Scott decision had opened the territories to slavery and that no group acting under the principle of popular sovereignty could keep it out. Douglas won the senatorial election, but Lincoln emerged from the debates as one of the nation’s most influential Republican spokesmen. George W. Rhiver, editor of the Decatur Republican, did his best to keep citizens of Decatur County informed Winter 2012 2/7/12 2:40 PM BLACK HISTORY NEWS AND NOTES TR ACE S Interior.indd 39 Winter 2012 39 2/7/12 2:40 PM An 1860 Currier and Ives drawing satirizing the antislavery orientation of the Republican Party’s platform. Abolitionist editor Horace Greeley (left) grinds his New York Tribune organ as candidate Lincoln (center, riding on a wooden rail) prances to the music. In the background William H. Seward holds a wailing black infant. At right stand two other New York editors friendly to the Republican cause, Henry J. Raymond of the New York Times (the short, bearded man holding an ax) and James Watson Webb of the New York Courier and Enquirer. about Lincoln and Douglas. One can imagine his excitement when he learned that both men, while on speaking tours in September 1859, would pass through his community. Neither man scheduled a speech in Greensburg, but their supporters hoped they would make a few remarks when their trains stopped at the depot on South Monfort Street. Douglas spoke in several Ohio cities in early September, giving his last speech of the tour on Friday, September 9, in Cincinnati. Talking for nearly two hours, Douglas declared that the Democratic Party stood “firmly by the principle of non-intervention by Congress with slavery anywhere, and popular sovereignty in the States and territories alike.” There was warm applause, but observers were con- 40 Interior.indd 40 TR ACE S vinced he had lost more influence in the South. On Saturday evening Douglas was received by admirers at the Greensburg depot, where a brass band played and “sky rockets” exploded overhead. A drunken man kept trying to grab Douglas’s hand when he gestured during his remarks. The Republican thought Douglas spoke “feelingly,” but there was little applause from the crowd. The senator must have been relieved as his train left Greensburg. Immediately below its account of the Douglas visit, the Republican published a paragraph with the title, “Hon. Abe Lincoln,” announcing that “the man who so completely flayed out the Little Giant, in Illinois last year, will speak in Cincinnati on next Saturday evening. He is expected to pass through our city on his way thither. Let our citizens give him a reception worthy of so great an expounder of Republican principles.” The newspaper was wrong about Lincoln coming through Greensburg on his way to Cincinnati, but he did pass through on his way home to Springfield, Illinois. He spoke in Columbus, Ohio, on September 16. The next day he spoke briefly in Dayton and Hamilton and made a long address in Cincinnati. Lincoln did not leave Cincinnati until Monday, September 19, although he had an address scheduled for Indianapolis that evening. He arrived in Greensburg around 3 p.m. “He was received at the depot by a large number of our citizens,” the Republican reported. “Flags were fluttering in the breeze and music from brass instruments resounded through the air. He Winter 2012 2/7/12 2:40 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG made but a few remarks to the crowd as the cars remained only for a short time.” It is unfortunate the Republican did not report what Lincoln said, but probably his remarks were similar to what he later said in Shelbyville. The Shelbyville Republican Banner reported that he noted that as he traveled through Indiana his thoughts “were carried back” to the time his father brought him from Kentucky to Indiana when he was seven years old. Lincoln recalled that he was “taught to cherish a strong and ardent sentiment in favor of liberty.” He reiterated what he had so often said: the government could not “endure permanently half slave and half free,” but he would not interfere with slavery where it existed under the Constitution. As weeks passed and there were more Lincoln speeches, many Republicans called for his nomination as the party’s presidential candidate. The Republican later claimed that in December 1859 it became the first Indiana newspaper to call for Lincoln’s nomination. This claim may have been true, but the issue that announced it is missing from the files. The Republican published everything it could about Lincoln and his supporters. The newspaper was especially impressed by a two-hour speech delivered in Greensburg by Benjamin Harrison of Indianapolis, a candidate for reporter of the Indiana Supreme Court. There were predictions that the young man, like his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, would someday become president. The most active Republican in Greensburg throughout 1860 was Cumback. When the Washington Township Republicans met in convention to choose a township ticket, it was he who acted as chairman. At the Republican state convention on March 1, he was declared a presidential elector at large. When the Republican National Convention opened in Chicago, he was present as an observer. “It was my good fortune to be acquainted with Lincoln personally before he was a candidate for President,” Cumback wrote in 1900. He visited Lincoln in Springfield for a pleasant conversation before going to Chicago for the convention, which opened on May 16. Cumback stressed that “ours was the only state, outside of Illinois, that on the first ballot gave a solid vote for Lincoln.” Before leaving Chicago, Cumback wrote Lincoln on May 27 to congratulate him on his nomination. Lincoln, saying “better late than never,” responded on June 15. “Mrs. L.,” he wrote, “remembers what you said about her being Mrs. President, and she pretends she did not believe a word of it. She sends her respects to you.” Closing, Lincoln asked, “How [do] the signs appear to you?” Lincoln’s letter is preserved in the Cumback collection in the Lilly Library at Indiana University, but the Cumback letter of May 27 and a reply to Lincoln’s letter of June 15 have not been found. While Cumback received more attention than any other Decatur County political leader in 1860, former congressman Foley and former sheriff Joseph V. Bemus- daffer quietly took part in one of the great political decisions of that year. They were two of the thirteen Indiana delegates to the Democratic National Convention that convened in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 23. Douglas was the strongest candidate for the presidential nomination, but southern delegates refused to vote for him because of his opposition to the Dred Scott decision and thus denied him the two-thirds majority necessary for the nomination. The convention again met in Baltimore on June 18. Many southern delegates did not appear and many who did soon withdrew. The Indiana delegation claimed that it had voted unanimously for Douglas forty-eight times. Ten days later the dissident Democrats nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge for president. The splitting of the Democratic Party virtually determined the outcome of the election, but both parties waged a lively campaign in Decatur County. The Democrats had a considerable following in the county’s southern townships, but the Republicans had drawn into their organization most of the former Whig Party, long The Greensburg Railroad Depot as it appeared many years after the Civil War. This building is beleived to be the depot at which the trains with Lincoln on board stopped at South Monfort Street in 1859 and 1861, and which was moved to South Franklin Street in 1865. TR ACE S Interior.indd 41 Winter 2012 41 2/7/12 2:41 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG Rival 1860 presidential nominees Lincoln and Douglas are matched in a footrace, in which Lincoln’s long stride is a clear advantage. Both sprint down a path toward the U.S. Capitol, which appears in the background right. They are separated from it by a rail fence, a reference to Lincoln’s popular image as a rail splitter. the county’s strongest political organization. A few Democrats supported Breckinridge. A still smaller group supported the Constitutional Union candidate, John Bell. Young men in Greensburg, Milford, and other towns formed “Wide-Awakes.” They wore uniforms, carried torches, exploded fireworks, sang songs, and shouted slogans urging Lincoln’s election. In Decatur County Lincoln received 2,028 votes; Douglas 1,946; Breckinridge 93; and Bell 20. When Indiana electors of the Electoral College met in Indianapolis on Wednesday, December 5, 1860, Cumback cast the first vote for Lincoln. 42 Interior.indd 42 TR ACE S When it became clear that Lincoln had won the election, his followers everywhere were exhilarated, but enthusiasm was soon dampened by worry. Secession began with South Carolina on December 20, Mississippi followed on January 9, Florida on January 10, Alabama on January 11, and Texas on February 1. A convention representing these states met in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4. Four days later the convention organized a provisional government. Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was inaugurated as president of the Confederate States on February 9, 1861. On Saturday, January 19, Decatur County Republicans and Democrats came together in a mass meeting. John DeArmond, former editor of the Greensburg Democrat, wanted condemnation of both southern secession and northern personal liberty laws that impeded “execution of the Fugitive Slave Law.” This the meeting refused to do. Instead, it endorsed a resolution that Fourth District Democratic congressman William S. Holman had introduced in the House of Representatives. Holman denied the right of secession and called for “employment of the army and navy as the exigencies of the case may require.” Cumback gave his strong support Winter 2012 2/7/12 2:41 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG for Holman, often his principal rival in the politics of the Fourth District, thereby winning high praise. The Republican noted that “Mr. Cumback is not a Constitutiontinkerer; but in the words of the resolutions adopted holds the provisions of the Constitution ample for the preservation of the Union, and that it needs to be obeyed rather than amended.” While people throughout the country tried to make sense of the crisis, Lincoln left Springfield at 8 a.m. on February 11, 1861. The president-elect spoke movingly to a large group of friends as he boarded the train. There were brief remarks at Tolono and Danville in Illinois and at the Indiana state line. At Lafayette, Thorntown, and Lebanon, Lincoln also spoke briefly, as well as speaking for a few minutes in Zionsville. Arriving in Indianapolis he offered remarks in response to the welcome of Governor Oliver P. Morton. That evening Lincoln spoke from the balcony of the Bates House, where he noted that the words coercion and invasion “were in great use about these days.” He thought that marching an army into South Carolina certainly would be an invasion, but asked if the government insisted on holding its forts or retaking them, enforcing U.S. laws and collecting tariffs, or withdrawing mails where mails had been violated, could that be called coercion or invasion? He thought that lovers of the Union who so interpreted the government’s actions were “of a very thin or airy character.” Lincoln had made his decision to confront the secession crisis, and to that decision he consistently adhered during the next four years. At 11 a.m. on February 12—his birthday—Lincoln, with his family, secretaries, and other associates, boarded a special train. The Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad had assigned a locomotive called the Samuel Wiggins, named in honor of a Cincinnati banker who was a director of the railroad and a strong supporter of the Union, to Lincoln’s train. Flags, bunting, and pictures of the first fifteen presidents of the United States and the presidentelect adorned the train. The railing of the last car was similarly decorated, and a gilded American eagle was at the center. In addition to the Lincoln party, many Cincinnati people were on the train. Cumback was aboard and doubtless had persuaded Lincoln to stop in Greensburg. Progress was about the usual rate—thirty miles an hour. Every half mile a man appeared with “the American flag as a signal of all right.” There was a stop at Shelbyville and then a stop at Greensburg, probably between noon and 12:30 p.m. At Greensburg “the surroundings were profusely decorated with flags;” Lincoln was greeted by “an immense and very enthusiastic gathering.” Artillery “roared” and a brass band played. As the presidentelect appeared, “a stentorian but by no means unmusical chorus sang ‘The Flag of our Union,’” the Cincinnati Commercial reported. The Chicago Tribune noted that Cumback introduced the president-elect. Lincoln told the crowd he had no time to make a speech. People surrounded the car; among them were children who had been dismissed from school. Lincoln shook Top: In addition to his political career, Will Cumback earned recognition for his writing ability. In his 1900 history of Indiana poetry, Benjamin Parker noted: “During all these years of public service Mr. Cumback kept his literary tastes and capabilities alive and active, delivering lectures and writing for the press. He has not written largely in poetry, but his few poems are of such a hopeful nature that they leave the reader happier for having read them.” Left: At the outbreak of the Civil War, Douglas spoke out against secession by the South from the Union. “There are only two sides to this question,” said Douglas before his death from typhoid fever on June 3, 1861. “Every man must be for the United States or against it. There can be no neutrals in this war; only patriots and traitors.” TR ACE S Interior.indd 43 Winter 2012 43 2/7/12 2:41 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG hands with many of them. Assisted by friends, the eighty-five year old Reverend James Blair got close enough to extend his hand, and Lincoln shook it warmly. Tears streaming down his face, Blair invoked the blessing of Heaven on the presidentelect. John Dokes of Marion Township, who had been a Wide-Awake despite his age, gave Lincoln “a very nice apple.” The band played “Hail Columbia” and the train pulled away. Cumback later told that Lincoln went to his car, sat down, and ate Dokes’s apple with relish. The Republican noted that after the train left a large crowd appeared at Pemberton and Hanna’s grocery store, which had reduced prices for the occasion. The newspaper noted that most people had been surprised that Lincoln was better looking than they expected. “He is not a beauty, but he is about as good looking as Presidents generally are,” the Republican concluded. Decatur Countians had witnessed, for a few minutes, an early stage of one of the longest and most important journeys to Washington of a president-elect in the nation’s history. Lincoln took full advantage of the many opportunities the trip afforded to speak to the American people. He spoke briefly in Lawrenceburg about two hours after leaving Greensburg. As the train entered Ohio at North Bend a few minutes later, it passed the tomb of William Henry Harrison, first governor of the Indiana Territory. Members of the Harrison family had gathered at the tomb to wave greetings to the president-elect. Lincoln, standing at the rear of the train, bowed in response. That evening he made two speeches in Cincinnati. He continued on his trip for ten more days, addressing the legislatures of Ohio, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. He spoke in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, New York, and Philadelphia, and he made brief talks from the train’s rear platform at many depots. Lincoln strengthened his popular support wherever he stopped. Always he upheld This Kimmel and Forster lithograph from New York is a grand allegory of the Civil War in America, harshly critical of the James Buchanan administration, Jefferson Davis, and the Confederacy. In the center stands Liberty, wearing a Phrygian cap and a laurel wreath. She is flanked by the figures of Justice (unblindfolded, holding a sword and scales) and Lincoln. 44 Interior.indd 44 TR ACE S Winter 2012 2/7/12 2:41 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG In artist Louis Maurer’s lithograph Lincoln and running mate Hannibal Hamlin are shown about to destroy a Democratic Party paralyzed by internal dissension. The Republicans ride a locomotive named “Equal Rights” toward a crossing where the wagon “Democratic Platform,” hitched to two opposing teams, is stalled on the track. Horses with the heads of Douglas and bearded vice presidential nominee Hershel V. Johnson pull toward the left. A team with the heads of southern Democrats John C. Breckinridge and Joseph Lane strain toward the right. Republican policies but tried to refrain from comments that might exacerbate tensions. Unfortunately those tensions grew worse as days passed, focusing more and more on Confederate demands for surrender of Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Excitement grew in Greensburg as news came from Charleston. Tip Kemper, who had been present when Lincoln appeared in Greensburg on February 12, wrote on April 10 that an attack on the fort was expected hourly and that the Stars and Stripes was “floating from each tower of the Court House here,” and that everyone was talking about the “War Question.” The next day two young men, James White and Polk Armington, raised a “Secession flag” from the west tower of the courthouse. They intended their action to be a joke, but the flag came down at once, and “Armington was kicked for his impudence.” War began at 4:30 in the morning of April 12 when Confederate forces commanded by General Pierre G. T. Beauregard opened fire on Fort Sumter. On April 14 the Union commander, Major Robert Anderson, surrendered. News from Charleston reached Greensburg by telegraph daily. People gathered in groups on the “Square” to discuss the crisis. They wondered what the president would do. On April 15 Lincoln proclaimed the existence of a rebellion and called “forth the militias of the several States of the Union, to the aggregate of 75,000” to suppress the rebellion. The War Department asked for six thousand troops from Indiana for three-month service. Everywhere in the state there was enthusiastic response. Decatur County men, most of them from Greensburg and Washington Township, hastened to enlist. They included men who would ultimately be recognized as some of the greatest Decatur Countians of the nineteenth century. Among them was Cumback. Orville Thomson, historian and journalist, was another. Kemper was also among them; he would have a distinguished career as a physician. Twelve members of the Brass Band, so conspicuous during Lincoln’s stop on February 12, were the first to go. They left on Saturday morning, April 20, and a large crowd gathered to bid them farewell. A larger group of volunteers left on Monday, April 22. “Their departure was witnessed by the largest crowd ever convened in Greensburg. Almost every man, woman, and child was affected to tears,” noted the Republican. The men from Decatur County were mustered in on April 25, 1861, as companies B and F of the Seventh Indiana Volunteer Infantry. Immediately after Lincoln called for volunteers, other states seceded—Virginia TR ACE S Interior.indd 45 Winter 2012 45 2/7/12 2:41 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG on April 17, Arkansas on May 6, Tennessee on May 7, North Carolina on May 20. Virginia’s secession meant a terrible danger to the Ohio Valley. What if the Confederacy should establish control over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, so essential to all inhabitants of the valley? Fortunately, many people of northwestern Virginia opposed secession and were concerned about access to the Ohio River. Their attitudes meant an opportunity for the Union, and the commanding general of the U.S. Army, General Winfield Scott, was quick to exploit it. He ordered the commander of the Ohio militia and other midwestern forces, General George B. McClellan, to send troops into western Virginia. McClellan sent the Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Indiana Regiments and the Fourteenth and Sixteenth Ohio Regiments. In Virginia they were joined by a Virginia regiment that was loyal to the Union. Later, it became the First West Virginia Regiment. The Seventh led an attack on Confederate troops in Philippi. Much of the fighting centered on a covered bridge that still stands. The battle began on June 2 and was over by early the next morning. This battle, the first land battle of the Civil War, could have been accurately described as a skirmish, but it was more decisive than many larger encounters. For a time the battle determined that the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad remained in Union hands. Before its three-month term ended, the Seventh took part in several successful operations. The Seventh and the other regiments in the campaign did more than keep a vital railroad under Union control. In doing so they helped make possible the secession of the northwestern counties of Virginia from that state and the creation, in 1863, of the state of West Virginia. Their achievements did much to enhance the reputation of McClellan, who became commander of the Army of the Potomac. As the Seventh was en route to India- A lantern slide from the McIntosh Stereopticon Company of Chicago depicting one of the famous Lincoln and Douglas debates in Illinois in 1858. The debates occurred in Ottawa on August 21, Freeport on August 27, Jonesboro on September 15, Charleston on September 18, Galesburg on October 7, Quincy on October 13, and Alton on October 15. 46 Interior.indd 46 TR ACE S Winter 2012 2/7/12 2:41 PM LINCOLN AND GREENSBURG large numbers to join regiments recruited for a few days. Most of them came to Greensburg, where there were supplies. While some of the raiders appeared in the southern part of the county and at New Pennington near New Point, they left without a battle. Lewis A. Harding in his History of Decatur County published in 1915, wrote that the county raised twentysix infantry regiments, and one battery, almost 2,500 men. Some men enlisted two or three times; Harding believed that this meant about two thousand had actually served. The total casualty list had 251 names. Fifty-eight men died in battles, six were frozen to death, twenty-two died in prison, two drowned, and 141 died of disease. The Greensburg depot was moved in Completed in 1860 at a cost of $120,000, the Gothic Romanesque-style Decatur County 1865 from South Monfort to a site on Courthouse at Greensburg was built of limestone and replaced the original 1827 structure. South Franklin Street now occupied by the Greensburg Daily News and there is nothtriumphs and safe return home,” wrote napolis for discharge, word came of the ing on South Monfort today to remind Thomson, who was on that train and in Confederate victory at Bull Run on July 1904 published a history of the regiment. one of the depot, which is unfortunate. 21. The Seventh’s officers realized that The Seventh served with great distinc- Some of the most memorable events in this meant a long war and that regiments would have to reorganize for longer terms. tion until it was disbanded in 1864. Other Decatur County’s history took place at the As they reached the Ohio River they began regiments that had companies made up of depot. Calvin D. Davis, professor emeritus of planning a regiment that would serve three Decatur County men also gave splendid history at Duke University, is best known for accounts of themselves. There were few years. On September 13 the reorganized his work with the pre-1914 movement for a major battles in any of the most imporregiment was again mustered into service world organization and the codification of tant theaters of the war in which soldiers in Indianapolis and at once ordered back from Decatur County did not participate. the international laws of war. His book, The to western Virginia. At about 7 a.m. on United States and the First Hague Peace Still, the county also experienced within Sunday, September 15, the train carryConference, won the 1962 Albert J. Bevits own borders harsh aspects of the war. ing the regiment, three companies of eridge Award, a prize given by the American which were from Decatur County, passed Opponents of the war rioted in GreensHistorical Association. Throughout his career through the Greensburg depot. There was burg on April 25, 1863, with less serious he has maintained an interest in Indiana incidents in several smaller communities. “a large concourse of citizens—fathers, history. Born at Westport in Decatur County, mothers, sisters, brothers, sweethearts and When Confederate General John Hunt Morgan and his raiders came near Decatur he now lives and writes in Greensburg, Indineighbors—who sped them on their way ana. This is his first article for Traces.• County in July 1863, men turned out in with assurance of prayers for their future FOR FURTHER READING Basler, Roy P., ed. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. 8 vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55. | Will Cumback Collection, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. | Harding, Lewis A. History of Decatur County, Indiana: Its People, Industries, and Institutions. Indianapolis: B. F. Bowen, 1915. | Searcher, Victor. Lincoln’s Journey to Greatness: A Factual Account of the Twelve-Day Inaugural Trip. Philadelphia: Winston, 1960. | Thomson, Orville. Narrative of the Service of the Seventh Indiana Infantry in the War for the Union. Baltimore, MD: Butternut and Blue, 1993. TR ACE S Interior.indd 47 Winter 2012 47 2/7/12 2:41 PM