* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Key Terms

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

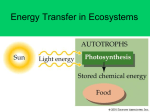

Objectives Contrast the flow of energy and chemicals in ecosystems. Explain how trophic levels relate to food chains and food webs. Key Terms producer consumer decomposer trophic level food chain herbivore carnivore omnivore primary consumer secondary consumer tertiary consumer detritus food web As small as it is, a terrarium like the one in Figure 36-1 is an ecosystem. A terrarium includes a community of organisms such as plants, snails, and bacteria as well as their nonliving environment—the soil, minerals, water, and air. Just as in larger ecosystems such as forests and streams, the terrarium illustrates two key processes of all ecosystems: energy flow and chemical cycling. Energy Flow and Chemical Cycling Every organism requires energy to carry out life processes such as growing, moving, and reproducing. Photosynthetic producers such as plants convert the light energy from sunlight to the chemical energy of organic compounds (Figure 36-1). Organisms called consumers obtain chemical energy by feeding on the producers or on other consumers. Finally, organisms called decomposers break down wastes and dead organisms. As living things use chemical energy, they release thermal energy in the form of heat to their surroundings. To summarize, energy enters an ecosystem as light, is converted to chemical energy by producers, and exits the ecosystem as heat. Energy is not recycled within an ecosystem, but flows through it and out. Producers must continue to receive energy as an input for the ecosystem to survive. Figure 36-1 As in larger ecosystems, energy flows through the terrarium ecosystem, while chemicals cycle within it. In contrast to energy, chemicals such as carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen can be recycled between the living and nonliving parts of ecosystems and the biosphere. In Concept 36.3 you will read about the different chemical cycles in more detail. Although energy flows through an ecosystem, while chemicals can be used again and again, the movements of both energy and chemicals are related to patterns of feeding within the ecosystem. Food Chains In the desert, a grasshopper munches on a brittlebrush's bright yellow flowers. Suddenly, a mouse seizes the grasshopper for its own meal. These feeding relationships, from flower to grasshopper to mouse, relate to how energy and chemicals move through the desert ecosystem. Each of these organisms represents a feeding level, or trophic level, in the ecosystem. The pathway of food transfer from one trophic level to another is called a food chain. Producers Figure 36-2 compares a terrestrial food chain and an aquatic food chain. In both food chains, the producers make up the trophic level that supports all other trophic levels. In terrestrial ecosystems, plants are the main producers. In aquatic ecosystems, phytoplankton—photosynthetic protists and bacteria—multicellular algae, and aquatic plants are the main producers. Figure 36-2 Each of these food chains includes five trophic levels. The arrows indicate the direction of food transfer between trophic levels. Consumers Organisms in the trophic levels above the producers are consumers. They may be categorized according to what they eat. A consumer (such as a horse) that eats only producers is an herbivore. A consumer (such as a lion) that eats only other consumers is a carnivore. And a consumer (such as a bear) that eats both producers and consumers is an omnivore. Consumers may also be categorized by their position in a particular food chain. For instance, when a consumer feeds directly on producers it is referred to as a primary consumer, or first-level consumer. In terrestrial ecosystems, primary consumers often include insects and birds that eat seeds and fruit, as well as grazing mammals such as antelope and deer. In aquatic ecosystems, primary consumers include a variety of zooplankton (mainly protists and microscopic animals such as small shrimps) that feed on phytoplankton. Secondary consumers (second-level consumers) eat primary consumers. On land, secondary consumers include many small mammals and reptiles that eat insects, as well as large carnivores that eat rodents and grazing mammals. In aquatic ecosystems, secondary consumers are mainly small fish that eat zooplankton. Tertiary consumers (TUR shee ehr ee)—third-level consumers—eat secondary consumers. On land, a tertiary consumer may be a snake eating a mouse. Some ecosystems, such as those in Figure 36-2, can even support quaternary (fourth-level) consumers. As you will read in Concept 36.2 the number of fourth-level consumers in an ecosystem is usually low. Decomposer At each trophic level, organisms produce waste and eventually die. These wastes and remains of dead organisms are called detritus. Decomposers are consumers that obtain energy by feeding on and breaking down detritus. Animals that eat detritus, often called scavengers, include earthworms, some rodents and insects, crayfish, catfish, and vultures. But an ecosystem's main decomposers are bacteria and fungi. These organisms, found in enormous numbers in the soil and in the sediments at the bottom of lakes and oceans, recycle chemicals within the ecosystem. Diagrams of food chains, such as those in Figure 36-2, generally do not depict the decomposers that break down the remains of the organisms at each trophic level in the food chain. But all ecosystems do include decomposers—their role is vital to the ongoing recycling of chemicals in the ecosystems. Food Webs The feeding relationships in an ecosystem are usually more complicated than the simple food chains you have just read about. Since ecosystems contain many different species of animals, plants, and other organisms, consumers have a variety of food sources. The pattern of feeding represented by these interconnected and branching food chains is called a food web. Figure 36-3 shows how food chains within a food web are interconnected. For example, the rattlesnake eats several animal species that may also be eaten by other consumers, such as the hawk. In addition, some consumers can feed at several different trophic levels. The woodpecker, for instance, is a primary consumer when it eats cactus seeds, and a secondary consumer when it eats ants or grasshoppers. The hawk can be a secondary, tertiary, or even quaternary consumer depending on its prey. Note that like food chains, food web diagrams typically do not show decomposers. In the next section you'll read more about how trophic levels in food webs relate to energy flow in an ecosystem. Figure 36-3 This food web diagram shows some of the interconnected food chains in the Sonoran Desert ecosystem. The arrows represent food transfer between trophic levels. Note that several species feed at more than one trophic level. Concept Check 36.1 1. How are the movement of energy and the movement of chemicals in ecosystems different? 2. In the following food chain, identify the trophic levels: An owl eats a mouse that ate berries. 3. Using Figure 36-3, identify a food chain with at least three trophic levels in the Sonoran Desert ecosystem (other than that featured in Figure 36-2). Copyright © 2004 by Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.