* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download hinduismUWO

Hindu nationalism wikipedia , lookup

Classical Hindu law in practice wikipedia , lookup

2013 Bangladesh anti-Hindu violence wikipedia , lookup

Brahma Sutras wikipedia , lookup

California textbook controversy over Hindu history wikipedia , lookup

Vaishnavism wikipedia , lookup

Dharmaśāstra wikipedia , lookup

Indra's Net (book) wikipedia , lookup

Tamil mythology wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Rajan Zed prayer protest wikipedia , lookup

Dayananda Saraswati wikipedia , lookup

Invading the Sacred wikipedia , lookup

Women in Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Hinduism in Malaysia wikipedia , lookup

History of Shaktism wikipedia , lookup

Anti-Hindu sentiment wikipedia , lookup

Neo-Vedanta wikipedia , lookup

Hinduism in Indonesia wikipedia , lookup

History of Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Hindu mythology wikipedia , lookup

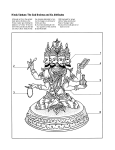

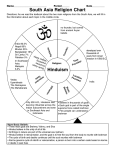

Goals of Hinduism (Hindu Students Organization, University of Western Ontario) The Hindu scriptures recognize four ends that humans may pursue in their lives. The first two are artha, which is wealth and power, and kama, which is pleasure and the satisfaction of desires, especially that of sex. Artha and kama are legitimate goals and are acknowledged as an important part of the needs of every man, but they are secondary to the two remaining ends of life: dharma, right conduct; and moksha, release from the cycle of unending rebirth. Dharma The goal most widely recognized among Hindus is dharma. In addition to morality and right conduct, it also signifies quality and duty. Dharma is eternal and immutable. It is also specific. All things, animate and inanimate, were assigned dharma at creation. The dharma of gold is yellow color and brightness; the dharma of a tiger is ferocity and eating other animals. A person's dharma, manavadharma, encompasses essential human qualities and characteristics as well as the conduct proper for every person. It includes respect for priests and scriptures, speaking the truth, abstaining from taking life, performance of meritorious acts, and worship of the gods. A person must also follow other dharmas, depending on one's position in life. One must follow the ordained norms of one's nation, of one's tribe or caste, of one's clan, and of one's family. Dharmas differ for men and women, for old and young, for married and single, and for rulers and common people; there are dharmas, in fact, for every major order of human differentiation. When dharmas conflict, that is, when duties toward one group conflict with duties toward another, the interests of the smaller group, such as the family, should be sacrificed to the larger, such as the caste. Faithful fulfillment of dharma is, in popular belief, the best way to improve one's condition in future lives. Thus, for most Hindus, especially the uneducated, dharma is the major goal of life. Since dharma is generally synonymous with custom, the result has been a powerful adherence to tradition, especially to that of caste. The Bhagavad-Gita states, "Better one's own duty [dharma], even imperfect, than another's duty well performed." Moksha While the overwhelming majority of Hindus regard the future of their souls only in terms of better rebirths, the highly influential philosophic stratum of Hinduism is concerned with moksha, complete release from rebirth. The soul is enslaved, they believe, to the never-ending wheel of reincarnation, which is powered by the law of karma. Philosophic Hinduism has recognized at different periods in history a number of techniques for achieving moksha. Although all of these are equally valid paths (margas) to salvation, three have achieved particular acceptance and sanction in the scriptures. The Path of Action (karma-marga) is the simplest path and the closest to the doctrine of dharma. Salvation by the karma-marga calls for a life of deeds and actions appropriate to one's station in life. But all actions must be performed selflessly, that is, without regard to gratification of personal desire. Such a life leads to detachment from the self and to union with brahman. The Path of Devotion (bhakti-marga) brings salvation through uncompromising devotion and faith to a personal god. Very often the object of devotion is the god Vishnu, or Krishna, one of his incarnations. Such devotion draws the believer closer to brahman (of which the god is a manifestation) and can generate the insight of the unity of all existence in brahman. The Path of Knowledge (jñana-marga) is the most sophisticated and difficult path to salvation. It calls for direct insight into the ultimate truth of the universe: the unity of brahman and atman. Such insight generally follows a long period of spiritual and physical discipline, which involves the renunciation of all worldly attachments and a rigorous course of ascetic and mystical practices. One of the most important such courses used by the followers of jñana- marga consists of a number of techniques known collectively by the name yoga. Yoga is a Sanskrit word meaning union or discipline; it is cognate with the English word ``yoke.'' The goal of the practitioner, called a yogi or yogin, is achievement of a state of samadhi, or dissolution of the personality, as a means of knowing brahman. The rigorous course of training followed by a yogi is nearly always directed by a guru, or spiritual teacher. It includes strict adherence to prescribed moral virtues, such as truthfulness, nonviolence, and chastity, training in control of the body and obliteration of the sense perceptions, extreme mental concentration, and meditation. Bodily control is an important part of yoga, and a trained yogi can achieve difficult postures, breathe through either nostril at will, and even stop the heartbeat. The basic form of yoga, which follows this pattern, is known as raja- yoga (royal yoga). Other variants include hatha-yoga (the yoga of force), which puts even greater emphasis on physical skills and acrobatics, and which regards sexual union as a means of salvation; mantra-yoga (the yoga of spells), which advocates repetition of magical phrases; and laya-yoga (the yoga of dissolution), which particularly stresses breath control and meditation. Basic Features Despite the contradictions among the many varieties of Hinduism, there are certain fundamental assumptions underlying most Hindu belief. Behind the ever-changing physical world is one universal, unchanging, everlasting spirit, known as Brahman. The soul, or atman, of every being in the universe, including the gods, is part of this spirit. At death the soul does not perish but passes, or transmigrates, to another body, where it is reincarnated as a new life. The fortunes of the soul in each rebirth are determined by its behavior in former lives. This law of karma (literally ``action'') states that no sin ever goes unpunished and no virtue remains unrewarded; if people do not receive punishment or reward in this life, they will in some succeeding life. By their behavior people determine whether their rebirth will be in a higher station or lower; rebirth may be as a human being, as a god, or as the lowest insect. Proper conduct, or morality, which governs a person's rebirths, is known as dharma. Hinduism lays down very specific rules of dharma, including special behavior appropriate to the members of each caste. All Hindus are born into such hereditary social groups, and most believe that a person's caste is determined by proper fulfillment of dharma. For the majority of Hindus, the doctrines of dharma, karma, and transmigration provide a satisfactory explanation of people's place and destiny in the universe. Many intellectual and philosophically inclined Hindus, however, have found these views emotionally and logically insufficient. For them, an endless chain of rebirths and redeaths seems pointless and even frightening. Their goal is not better rebirths but moksha, or complete release from the entire chain of reincarnation. Although exact means for attaining the salvation of moksha differ according to the particular schools and sects of Hinduism, the process typically involves withdrawal from active participation in everyday human affairs, ascetic behavior, and, ultimately, insight and release acquired through meditation. For most Hindus, the gods also play an important part in religious belief. Hinduism has hundreds of gods, ranging from lesser local deities to major gods, whose exploits are known in every household of India. Among the best-known gods of Hinduism are Vishnu; Rama and Krishna, two forms, or incarnations, of Vishnu; Siva (Shiva); and the creator god Brahma. Scriptures play a major role in all varieties of Hinduism. Philosophical Hinduism emphasizes such classical Sanskrit works as the Vedas and the Upanishads. Popular Hinduism, while revering the Vedas and Upanishads, uses as its texts the stirring epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, often translated into vernacular languages from the original Sanskrit. One section of the Mahabharata epic, called the Bhagavad-Gita, is known by nearly every Hindu. It is the closest that Hinduism comes to having a universal scripture Gods and their Cults In Hindu belief, divinity is an extension of the universal spirit brahman. Like brahman it is infinite and found in every portion of the universe, manifested in many different forms. Thus, although the Hindus have many gods, the gods have a oneness in brahman; they are all the same divinity. In the Bhagavad-Gita, the god Krishna says, ``Whatever god a man worships, it is I who answer the prayer.'' Most Hindu families favor for worship either Vishnu, Siva, or a Shakti, the wife or female companion of a god, as the supreme manifestation of brahman. Vishnu Vishnu is often known as the Preserver, in distinction to Brahma the Creator and Siva the Destroyer. He has been reborn, according to his devotees, the Vaishnavas, in a number of incarnations, or avatars, each time to save the universe from a catastrophe. Vishnu is generally represented in art as dark blue in color, bearing in his four hands his symbols: the conch, the discus, the mace, and the lotus. Sometimes he is resting on the coils of a many-headed snake, Ananda, with his wife, Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune, sitting at his feet and the Brahma-bearing lotus growing from his navel. At other times he is astride his mount, the eagle Garuda. Vishnu's avatars are Fish, Tortoise, Boar, Man-Lion, Dwarf, Rama with the Axe, Rama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalkin, who has not yet appeared. The inclusion of Buddha among Vishnu's avatars is typical of Hinduism's tendency to assimilate all faiths; some Hindus add Christ to the list as yet another avatar. The avatars of Vishnu most widely worshiped, especially in northern India, are Rama and Krishna. Rama, the princely hero of the epic Ramayana, is the perfect ruler, and his wife Sita is the ideal of Hindu womanhood. Because of the devotion of this couple to each other, young married couples are often called Sita-Ram. Krishna, the most frequent object of bhakti, is worshiped as a powerful but mischievous child, as a dark-skinned erotic youth who plays his flute and sports with the milkmaids, especially with Radha, his favorite, and as the adult hero of the Mahabharata epic and preacher of the Bhagavad-Gita. Siva Siva, the Destroyer, has many aspects. His devotees, the Shaivites, hold that destruction necessarily precedes creation and that Siva is, therefore, also the god of creation and change. Siva is portrayed in many different ways. Sometimes he is seen as an ash-white ascetic in a state of perpetual meditation, seated on a tiger skin high in the Himalayas. Cobras coil his neck and arms. The crescent moon is fixed to his matted topknot of hair, from which springs the sacred River Ganges. Sometimes he is Nataraja, who whirls about gracefully, maintaining the cosmos by his unending dance. Siva is often accompanied by his wife Parvati and his bull, Nandi, which serves as his mount. He is most frequently worshiped as a simple rounded post, usually of stone. This post is the lingam, or phallic emblem, of Siva and may indicate his origin as a fertility god. Shaktis The Shaktis are female divinities, generally the consorts of the gods Vishnu and Siva. To their cultists, the Shaktas, they represent the active forces of their husbands and the personified power of brahman. Most often worshiped is Siva-Shakti, the consort of Siva. She appears in many forms. As Parvati, Uma, or Annapurna she is a beautiful woman. But she is also a fierce and terrible goddess in the forms of Durga, Kali, Chandi, or Chamundi. Durga, a stern-faced warrior, sits astride a lion and bears an assortment of deadly weapons in her hundred hands. Kali, a charcoal-black ogress with a protruding blood-red tongue and terrible fangs, wears about her neck a garland of human heads and carries a blood-stained sword. Kali is associated with disease, death, and destruction, but she is also a protector of the faithful. She is worshiped, often with animal sacrifice, as Mata, the Divine Mother. Some Shakta cults have carried their worship to an extreme that is not generally well-regarded in Hinduism. These Tantric sects, so called from their sacred scriptures, the Tantras, include in their initiation rites the breaking of orthodox taboos, such as eating meat, drinking alcohol, and engaging in illicit sexual intercourse. The Tantrists prefer magical rituals and the recitation of mystical utterances (mantras) over karma-marga, bhakti-marga, or jñananamarga as the means to salvation. Other Gods Hinduism has many other gods, who are worshiped on special occasions or for special purposes. The most popular of these is Ganesha, the elephant-headed son of Siva, propitiated before undertaking most practical enterprises. Skanda, or Kartikeya, is another son of Siva, particularly popular in southern India. Frequently worshiped is the monkey-headed Hanuman, faithful ally of Rama in the Ramayana epic. Sitala, the goddess of smallpox, is also widely propitiated. Although Brahma figures importantly in mythology as the Creator, he is not generally worshiped. However, his wife, Sarasvati, is loved as the goddess of music, art, and learning. There are also hundreds of lesser local gods. The Hindu villager recognizes tutelary deities for all the hills and streams around his village. The village potter also worships the deity in his wheel, and the farmer worships the god of his plow. Divinity, in popular Hinduism, is universal. Religious Life & Practices Although temple worship does occur, Hinduism is not basically a congregational religion. Most Hindu religious activity centers in the home, involving only an individual, or perhaps a few friends or relatives. The most common type of religious rite is the puja, or worship service. In nearly every Hindu home there are sacred pictures or images of favored gods before which the puja prayers are chanted, hymns sung, and offerings made. In the simplest homes puja is a modest ceremony. The mother of the household recites prayers at dawn and rings a small bell before several bazaar-bought colored pictures of the gods in one corner of her room. In the richer households puja may involve elaborate offerings of food, flowers, and incense in a family shrine room containing decorated altars, icons of one or more gods and goddesses, and a sacred perpetual fire. In such homes a family priest, or purohit, may be called in on special occasions to aid in the puja. Such devotional services are performed particularly among adherents of the bhakti stream of Hinduism. To indicate their cult affiliation the worshipers often have colored marks painted on their foreheads and occasionally on their bodies. Shaivites typically mark themselves with three horizontal white lines, while Vaishnavas use a white V bisected by a vertical red line. Many family rites center on the important transitions of life. The family priest, generally a Brahmin for the higher castes, officiates at these rites, reciting from the sacred scriptures and directing the offerings to the gods. The birth ceremony takes place before the umbilical cord is cut, and about 10 days later there is a naming rite. Among the highest castes, the upanayana rite is performed when a boy reaches puberty. At that time he is invested with a sacred thread, which he wears across one shoulder for the rest of his life. The lengthy and complex Hindu marriage ceremony requires the couple to walk around a sacred fire with their garments knotted together. The couple recites vows of an eternal bond. In most parts of India widows may not remarry, and formerly many high-caste Hindu widows burned themselves on their husband's funeral pyres. Most Hindus dispose of the dead by cremation. The corpse is burned shortly after death and the ashes are thrown into the Ganges or another sacred river. For about 12 days after the cremation, members of the family give daily offerings of rice balls and milk to the deceased to prevent his or her ghost from doing harm. Among the orthodox of the highest castes, his shraddha rite is performed periodically by descendants of the deceased for several generations. Domestic religious activity, particularly in the villages, also involves worship at sacred sites, such as special trees, streams, and stones. Two species of trees, in particular, are considered sacred, the banyan and the pipal, a variety of fig tree. A number of animals are also venerated. These include monkeys, associated with Rama, and snakes, especially the cobra, associated with Siva. The most revered animals, however, are bulls, also associated with Siva, and cows, which represent the earth. All cattle are inviolate, and beef is eaten by very few Hindus. In the villages, cow dung is used widely for purposes of ritual purification and for making sacred images. On special occasions the cattle are decorated with bells and gaily colored streamers. Communal and temple ceremonies are more elaborate than domestic worship. Congregants gather to sing hymns and to read responsively with the priests from the Ramayana epic and other traditional literature. Festivals devoted to the temple gods are attended by pilgrims from a large area. In the temple a procession of temple servants with flutes, drums, and torches may ceremoniously escort the god to the shrine of his goddess to spend the night. There is often singing, dancing, and recitation from the epics. The largest temple festivals, such as the Jagannatha festival in Puri, Orissa, draw pilgrims from all over India. A huge image of Jagannatha, a horselike form of Vishnu (and the source of the English word ``juggernaut''), is placed on a wooden cart and pulled by devotees through the streets of the city. Pilgrimage is an important feature of Hindu religious life. There are hundreds of sacred places in India where the faithful can go to participate in temple festivals and religious fairs and to bathe in sacred rivers. The most important sacred places are Banaras (Varanasi), Hardwar, Mathura, and Allahabad in northern India; and Madura, Kancheepuram, and Ujjain in central and southern India. The calendar of festivals varies from one part of India to another. Perhaps the most widely celebrated festival is Divali, held in late October or early November. It is primarily a New Year festival but has other special significance in different regions. During Divali, ceremonial clay lamps are lit, presents are exchanged, and prayers are typically addressed to Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and good fortune. Holi, a spring festival, is marked by street dancing and processions, bonfires, and generally unrestrained festivities. Celebrants throw colored powders at each other and squirt each other with colored water. Other popular festivals include Dashara, celebrated by north Indian Vaishnavas; the Ganapati Festival of Maharashtra; the Dolayatra, or Swing Festival, of Orissa; and Pongal, the Rice-Boiling Festival, of southern India. Scriptures There are two main categories of Hindu scriptures, sruti, or divinely revealed works, and smriti, traditional works of acknowledged human authorship. All of the sruti literature is in Sanskrit, the language of ancient India; the smriti literature uses both Sanskrit and regional vernacular languages. The major sruti work is the Veda (``Wisdom'') composed between 1500 b.c. and 900 b.c. The Rig- Veda, the first of four parts of the Veda, contains hymns addressed to the male gods who were worshiped in India at the time. The other Vedas contain various ritual formulas, charms, spells, and incantations. Between 800 b.c. and 600 b.c. a series of prose expositions were written on the four Vedas. Known as the Brahmanas, they deal in meticulous detail with complex sacrificial rites surrounding worship of the Vedic gods. About 600 b.c. a number of further commentaries called Aranyakas appeared. They explore the symbolic meanings of the Brahmanic rituals and suggest that knowledge of the meaning of ritual is more important than its correct performance. Over a long period, from before the latest Brahmanas until well after the latest Aranyakas, a series of writings known as Upanishads were composed. Although the Upanishads are not entirely consistent in their philosophical position, they stress the concepts that still dominate. Hinduism today: the allpervasiveness of brahman, the unity of brahman and atman, the doctrines of karma and the transmigration of souls, and the theme of escape from rebirth. This entire body of literature, Vedas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads, is sacred. In many regions of India it is in the exclusive custody of the Brahmins and may not even be seen by people of lower caste. Unlike the divinely revealed sruti literature, the smriti works may be read by anyone. Most are either sutras, brief aphorisms compiled for easy memorization, or shastras, treatises elaborating a variety of topics. The Hindu goals of artha, kama, and dharma are represented by the Arthashastra of Kautilya, a treatise on kingship and the exercise of power, the Kamasutra of Vatsyayana, a text on sexual pleasure, and numerous Dharmashastras, codes of law and morality by Manu, Baudhayana, Yajnavalkya, and others. The two most popular portions of smriti literature are the epic poems Mahabharata and Ramayana. Both were composed over a long period of time from a blend of folk legends with many philosophical interpolations. The Mahabharata tells the story of a dynastic struggle and a great war. It contains within it the Bhagavad-Gita (``Song of the Lord'' ), one of the most important of all Hindu writings. The Gita, as it is often called, takes the form of a sermon by Krishna and outlines the fundamentals of the three paths to salvation, jñana, karma, and bhakti. The Ramayana tells of the adventures of Rama and his wife Sita. The epic is full of action, including a kidnapping of Sita by a demon and her dramatic rescue by Rama and his friend Hanuman, the monkey-headed god. Its ethical content is great and it is the most popular scripture in the villages of India. Its stories are often given dramatic and dance presentations. Other Hindu literature includes the Puranas (``Ancient Stories''), collections of legendary material and religious instruction, and devotional literature. Two famous Vaishnava works in these categories are the Bhagavata Purana, which recounts the life and teachings of Krishna, and the Gita Govinda, a Bengali work that describes Krishna's love for Radha.