* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Emperors of the Flavian Dynasty

Survey

Document related concepts

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Late Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman emperor wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

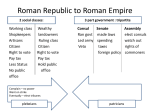

Fronda 1 Nicole Fronda Ms. Casey English 10 - period 4 20 November 2007 The Emperors of the Flavian Dynasty The years between A.D. 69 to A.D. 96 were one of the best years of the Roman Empire. This period of time was called the Flavian Dynasty. It was the birth of this dynasty that turned Rome into complete and permanent monarchy. During this time, one can see the beginnings and early stages of the Pax Romana. More importantly though, this was a time that Rome thrived. The impact of the Flavian Emperors on Roman society caused a revival of arts, education, entertainment, sports, architecture, and the restoration of the wealth of the Empire. Rome flourished during the Flavian Dynasty as the three Flavian emperors, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, created a new, peaceful, and prosperous time for the Roman Empire. Before the Flavian Dynasty, there was a time of great turmoil. After the Julio-Claudian Dynasty ended, Rome was in a state of disrepair. The treasury was unstable, due to the infamous Emperor Nero’s excessive spending and building projects, and there was still much rubble and ruins left over from the Great Fire. With the death of Nero, who had no heir, the position of emperor remained open. Many generals fought for this position, and those few that were able to defeat their rivals and gain the support of the military were rewarded the power of emperor. However, that power was continually shifting, as the military was quick to change leaders if they found another stronger than their own. For one whole year, A.D. 69, there were no strong leaders in the Roman Empire. This was called The Year of the Four Emperors. The first three, Galba, Otho, and Vitellus, who were able to defeat their opponents and claim themselves emperor, found their reigns to be short-lived as new adversaries came to defeat them and seize Fronda 2 the throne. This cycle of war and conflict continued until one man put an end to all the chaos. Vespasian was the last of the Four Emperors of A.D. 69. His accession made way for the new Flavian Dynasty, a new period of glory for Rome. Vespasian and his successors, Titus and Domitian, restored the Empire and finally brought peace and an end to all the disorder. One of the things that each of the Flavians did when they became emperor was stabilize the erratic treasury, and use the money in more resourceful ways. The treasury had slowly been depleting after the reign of Emperor Claudius, due to wars and lavish spending. Vespasian solved this problem by inaugurating a number of policies and ideas, most of which continued to be used under Titus and Domitian. To increase the flow of money and to keep fixed finances in the treasury, he renewed old taxes and introduced new ones. An example of these, is the infamous Urine Tax in which Vespasian “had imposed on the contents of the city urinals” since it was being collected as a source of ammonia to wash clothing (Suetonius, “Twelve” 294). He raised the tribute and the amount of money coming from the provinces. He also kept a close watch on the treasury to see that there was no frivolous spending. Although Vespasian was strict about the finances of the Empire, he was “very generous to every class of person” and was glad to give money to anyone who needed it (Suetonius, “Flavian” 20). This trait was also shared by his sons, especially Titus. After the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, Titus sent money and reassigned property to those who survived. Similar gestures from Titus were again shown after the great fire of Rome of A.D. 80, which “lasted for three days and as many nights”, and during an “unprecedented plague of great magnitude” (Suetonius, “Flavian” 26). Unlike some previous emperors, Vespasian and Titus used the Empire’s money wisely and the people of Rome loved their generosity. With the new steadfast treasury, the Flavian Emperors continued to invest in other ways that pleased the Empire. Of all the great things the Flavians did, the most memorable would be the numerous Fronda 3 building projects that each conducted. The most famous of these is the Flavian Amphitheater, more commonly known as the Colosseum. Vespasian began the project in A.D. 70, near the spot where Nero’s statue and his Golden Bath House was built. The Colosseum was a great phenomenon. Able to seat thousands of people, anyone could come to experience gladiatorial games, sports, executions, plays, and all other kinds of entertainment. The Colosseum was not finished until A.D. 80 during Titus’s reign and continued to have improvements made throughout Domitian’s reign. Besides the Colosseum, Vespasian also spent money on the restoration of many buildings in the capital that had been destroyed during Nero’s Great Fire in A.D. 64, and the construction of the Temple of Peace and the Temple of Claudius on Caeline Hill (Suetonius, “Flavian” 17). Though Titus’s reign was short, his few building projects included his own bath house that neighbored the Colosseum, which was conveniently completed at the same time. Unlike Titus, Domitian conducted many projects during his long reign. He built the Arch of Titus shortly after his brother’s death in A.D. 81 as a tribute to Titus’s triumph in Jerusalem. Domitian designed monuments such as “the Forum of Nerva, ..., a stadium, a concert hall, and the artificial lake for sea-battles - its stones later served to rebuild the two sides which had been damaged by fire”(Suetonius, “Twelve” 306). He also restored some important buildings, like the Capitol, which had been “gutted by ruins” and destroyed by fire (Suetonius, “Twelve” 306). Domitian also built a Temple to Jupiter on Capitol Hill, a palace on Palatine Hill, and a temple of the Flavian clan, which he dedicated to Vespasian and Titus (Suetonius, “Twelve” 31-32). Although much money had been spent on these architectural glories, and especially on Domitian’s part, it brought joy to the Empire to know that their emperors had the capabilities to make Rome magnificent and beautiful again. Besides beautifying Rome by restoring buildings and creating new elaborate edifices, the Flavians revived a new love for arts and entertainment in all the people throughout the Fronda 4 Empire. The Flavians were generous supporters of the arts, especially Vespasian who “was interested also in the arts for their own sake” (Woodside. 129). He was a devoted supporter of poetry, and presented many notable poets to the public, probably using them as propaganda, and paid them large amounts of money. He was also a benefactor of ancient literature and rhetoric and “ was the first to establish an annual salary of 100,000 sestertii for Latin and Greek teachers of rhetoric” (Suetonius, “Flavian” 20). Vespasian believed greatly in the importance of education and granted teachers immunity and protection against injury “because their utility to society was recognized by Vespasian” (Woodside. 128). Vespasian was also a patron of drama and theater, and “brought back the old entertainments too” (Suetonius, “Flavian” 20). He restored the Theater of Marcellus and payed thousands of sestertii to actors and musicians. Titus, however, was not particularly interested in theater entertainment, but rather athletic sports and games. With the completion of the Colosseum, he launched the inaugural games that lasted for one hundred days. Titus always “put on a most sumptuous and magnificent gladiator show... he also put on a naval battle in the old enclosure for naval battles” (Suetonius, “Flavian” 25). However, it was during Domitian’s reign that Rome was most entertained. Domitian “presented magnificently extravagant entertainments in the Colosseum and the Circus” which included chariot races, battles for infantry and cavalry, naval battles, beast hunts, and gladiatorial fights (Suetonius, “Twelve” 305). He also held the Secular Games and the Capitoline Games, which included foot races, horsemanship, and gymnastics. Domitian was also a sponsor for beauty contests, orators, singers, musicians, poets, actors, and play writes. After so much suffering and hardship, the Flavians brought new entertainment and art into the Empire, returning cheer and happiness to the people. Although the Flavians have done many great things for the Roman Empire, there are records of contrary evidence, especially in Suetonius’s works, that present the Flavian Emperors Fronda 5 in a less glorifying point of view. Vespasian had restored the money problems of the Empire and had been very generous to the people, but some accounts say that he was actually a very greedy man. He overtaxed the citizens, “for he was not contented with reimposing taxes which had been dropped...nor with increasing the tribute... and in some cases even doubling it” and also practiced illegal businesses (Suetonius, “Flavian” 19). There was also belief that he resorted to looting and plundering. He even sold public offices and granted acquittal to defendants, innocent or guilty, who were able to pay money so they could avoid trial. Titus had also been considered kind and generous by the people, but was accused of leading a brutal and anarchic lifestyle. Often times, when acting uncivil and violent, he would not hesitate to condemn a man to execution or to have them whipped and beaten. There were also many rumors of Titus “having a libidinous nature on account of his troops of lecherous men and eunuchs”, but no such substantial evidence has been found (Suetonius, “Flavian” 25). Domitian also has much contrary evidence, more so than his father and brother, that reveal him to be the worst of the Flavian emperors. Because of his excessive spending, Domitian had to reduce the number of soldiers in the military since he could not pay their salaries and he had to devalue the currency, which caused inflation. He was also a persecutor of the Jews, often making them pay more for taxes. Other evidence about Domitian shows he was “endowed with a cruelty that was not only great, but also artful and unexpected” (Suetonius, “Flavian” 35). He put to death many senators and other officials, he practiced the most obscene forms of torture, which included setting fire to a man’s genitals, and “through these deeds he became an object of fear and hatred to all” (Suetonius, “Flavian” 37). On the other hand, even with all the negative evidence, one cannot deny that the Flavians were good emperors who devotedly contributed to the Empire in order to make it better. Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian made the Flavian dynasty one of the most peaceful, Fronda 6 prosperous, and memorable times of the Roman Empire. Financially, architecturally, and culturally, they restored and improved the Empire, bringing joy and happiness to the people. Although the years between A.D. 69 to A.D. 96 were not completely without troubles, it is clear that the Flavian Emperors had indeed, once again, like other great emperors of Rome, brought a flourishing glory to the Roman Empire and created a period of time that will continue to be remembered and studied for centuries. Fronda 7 Works Cited McCrum, Michael. Select Documents of the Principates of the Flavian Emperors. London: Cambridge University Press, 1966. Suetonius. The Flavian Emperors. Trans. Brian Jones and Robert Milns. Ed. John H. Betts. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2002. Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Trans. Robert Graves. Ed. Michael Grant. New York: Penguin Books,1979. Woodside, M. St. A. “ Vespasian’s Patronage of Education and the Arts” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 73. (1942): 123-129. 16 October 2007 <http:www.jstor.org>.