* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Text

Athenian democracy wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

Acropolis of Athens wikipedia , lookup

Greek Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek religion wikipedia , lookup

Second Persian invasion of Greece wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Eurymedon wikipedia , lookup

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Corinthian War wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

\chapter{Plato}

\label{plato}

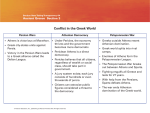

1.4 Classical Greece

Classical Greece By about 500 B.C. a number of transitions had taken place in Greece. Both

Sparta and Athens were completing their separate and distinct evolutions toward their

familiar future roles. The so-called Athenian ''Age of Tyrants'' had ended with the

beginnings of law-like structures first associated with Draco, who was an Athenian politician

and actually the scribe who codified the harsh measures of offense/punishment in 621. The

word ''draconian'' is reserved for measures which are overly harsh, as they stem from the use

of the death penalty for the merest offenses in this first attempt. The Athenian penal code

was greatly modified in 594 in a move attributed to the statesman Solon, who led the city

during a time of considerable internal unrest of both an economic and political sort. He

revamped the constitution and forgave debt which was a terrific burden on the agricultural

segment, basically standing up to an aristocracy which had become too severe. His

modifications of Draco's Code actually became the basis of the long-lasting Athenian law

and his opening of the land-holder assembly was the basis of democracy as it evolved.

But, in character with the Greek penchant for squabbling, Athens again fell into tyranny with

the emergence of Pesistratos, who with backing from Attic mountain people, eventually

seized power and was successively deposed and reinstated three separate times, over 12

years. Perhaps he symbolized the mixed meaning of ''tyrant'' for these times. He was

instrumental in promoting economic progress and also patronized an artistic and scholarly

attitude in the city. With his two sons, Hipparchos and Hippias, he ruled until his death in

524. The, in characteristic Greek fashion, Hipparchus was assassinated, and Hippias exiled

leading to the eventual installment of Kleisthenis in 510. It was under his rule that Athenian

democracy began to take real shape. Of course, during this entire time, Athens was at war

with neighboring states but nothing was to compare with the challenge that would bring all

of Magna Gracea together in defense against Persia.

The Persian War During the late Archaic period in Greece, the dominant power in the East

was the Assyrian Empire, ruling the entirety of modern Iraq, eastern Turkey, Palestine, and

the Nile valley. Under Nebuchadrezzar II, a neo-Babylonian empire arose out of the breakup

of the Assyrian goliath and was dominant until 539, when the Persians (modern day Iran)

pushed west and north to the southern rim of the Black Sea and south through Syria and

Palestine, into the Nile valley. The Persian empire was founded in one generation by Cyrus

the Great and with astonishing speed eventually stood literally at the doorstep of Athens. By

540 B.C., his son, Darius, had completely subjugated the Ionian countries, up through Troy,

and down through Thrace. War was inevitable. Although Athens made a half-hearted

defense of Ionia,

Section 1.4 Classical Greece 21 it could not single-handedly defeat the most fearsome force

that the world had ever known. In 490, on the plains of Marathon the Athenians won a

decisive battle, memorialized by the 26 mile run of the messenger Phidippides to bring the

news. The small Athenian force of less than 10,000 men had, through shrewdness and

surprise, killed more than 6,000 Persians while suffering only minimal loss themselves.

Everyone knew it was coming as all watched, now under Xerxes' command, as in tandem the

Persian infantry marched along in parallel to the Persian navy around the inside of the

Aegeatic basin. The ''attack'' took 10 years to muster and in 480, battle was joined with an

amassed Persian force of at least 150,000 soldiers and 600 warships. Athens was evacuated

and left for the Persians who destroyed it. With the impending war, the Greek confederation

organized itself with only 31 of the hundreds prepared to fight. The city-states of importance

were Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Aegina with Athens mounting the naval campaign and

Sparta the foot soldier command. What followed were a series of military maneuvers that are

still studied today, with Spartan heroism of their King Leonidas with 300 Spartan troops and

a total of 9,000 allied soldiers met and slaughtered the Persians at the pass at Thermopylae.

Leonidas and his Spartans stood their ground and all were killed after a Greek traitor told

Xerxes of a backdoor route to entrap the Greeks. While this was going on, the Athenian

navy was engaged with the much larger force in the decisive battles of Artesmisium and

subsequently, Salamis. Here the Persian fleet was so cramped in narrow waters that the

Greeks were able to strike at will, moving nimbly among them, boarding with Spartan

''marines'' and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. Reported, Xerxes himself sat on a throne at

water's edge increasingly furious as his navy was thwarted. The Persians lost half of their

navy in these legendary battles and retreated to central Greece for the winter. During the

summer of 479 B.C., the Persians were defeated in a decisive battle at Plataea and then at the

urging of the Ionians, they were pursued to Mycale both on-shore and naval forces were

destroyed by the Spartan commander, King Leotychidas. The Persians fled the Aegean

leaving behind a Sparta with greatly enhanced reputation and an Athens, proud but totally

destroyed.

Consequences of the Persian War While the overall destruction must have been numbing for

the Greeks, there were two critical results which had long-lasting consequences for Greek

history. The first is a nearly scientific outlook, brought about by one man: Herodotus'

//Histories//, his famous account of the Persian Wars. The second was the creation during the

wars of the Delian League of Greek city-states.

The idea of a history was not a natural thing. In the 5th century B.C. analysis of events for

meaning or cause had never been done in a systematic way. Rather, Homeric accounts of

political upheaval were still the expected norm: events which befall nations are beyond the

control of people. One looked back Section 1.4 Classical Greece 22 in order to praise heroic

deeds, but analyzing the causes of conflict had simply never been done. So, it may be hard to

appreciate, but the modern idea of a History was essentially the invention of one man,

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (ca. 484-425 B.C.).

Little is known of the details of his life. It appears that as a young man he was exiled to

Samos from Halicarnassus as as result of being on the wrong side of a coup against the

rulers (Halicarnassus was a Dorian city-state on the southern portion of Ionia). This must

have stimulated his extensive travels: he visited the Nile valley in Egypt and Mesopotamia,

as far as Babylon, went north to the Ukraine, and west to Italy and Sicily. Herodotus

critically reviewed what he saw and interviewed people as he went along. Eventually, he

settled in Athens and apparently recited his summaries as verbal prose (not poetry) accounts,

eventually writing them as his //Histories//. This work, divided later into nine books each

named for the ancient muses, are a wide-ranging account of what he saw as he traveled,

around the larger theme of trying to understand the cause of the Persian wars: ''Herodotus of

Halicarnassus hereby publishes the results of his inquiries, hoping to do two things: to

preserve the memory of the past by putting on record the astonishing achievements both of

the Greek and the non-Greek peoples; and more particularly, to show how the two races

came into conflict. In essence, this statement ushers in the birth of History as a

discipline---an accounting of the actions of people and an analysis of the causes that brought

about important events. What's completely new is the //presumption// that there are causes

for such things and that they can be dispassionately analyzed. The supernatural has no place

in his accounts. More abstractly, his linear presentation actually adds to the growing

appreciation of Time as an unfolding concept.

Herodotus made mistakes---wondering aloud about how annual Nile flooding could be as a

result of ice melting in a hot-part of the world. But, he also reported things that he did not

believe, but thought important: that Phoenician sailors reported sailing west, seeing the sun

on their right (suggesting to us that they had sailed far below the equator). The first part of

the //Histories// details the rise of Persia and the latter part, the wars with Greece and their

eventual triumph. Remarkably, he did this without appearing to pass judgement: he reported

and analyzed. Of course, this ''taking it as it appears'' is vaguely scientific in character and

the lack of reliance on the Greek Gods as cause is reflective of the emergence of independent

thought.

The second important consequence of the Persian conflict is historically important.

Remember, the Persian ''attack'' was not exactly sudden and the Greek world has plenty of

opportunity to prepare its defense. One of the first steps was a conference of Greek city

states at Delos at which, with Athenian leadership, the Delian League was formed in 477.

Ostensibly, this was an effort to collect resources (from those cities who were not directly to

prosecute the war) or ships and men (from those cities who Section 1.4 Classical Greece 23

would) according to strict and taxing quotas. Athenian influence grew to the point when the

funds and management moved to Athens. Success against Persia was due in part to the

foresight of the Delian League. Once the war was over, the alliance remained in tact as a

means of protecting the Greek nation from repeated attack---as a permanent bond, and city

states were sometimes forced to remain steadfast. Such was the beginning of the Athenian

empire. Ironically, even though Sparta could be credited as having been the major military

force in the Greeks' victory, its isolated and belligerent nature simply did not equip it to lead

during peacetime. In contrast, while Athens had been destroyed, its nature was to rebuild

stronger, to politically organize, and to lead. This is the beginning of the Classical Age,

synonymous with the Athenian Age.

Athens

The growing power of Athens, which fed their natural tendency toward feeling good about

themselves, combined with two circumstances: the riches gained during the war and the

emergence of a singular, political leader. Pericles (495-429 B.C.) was only 18 when the

Persian War concluded and so he must have been a part of both the evacuation and the return

to a devastated Athens. As a child from a political family, it was a forgone conclusion that

politics would be in his future. (He could count as a distant relative, the great Athenian

reformer Kleisthenis.) His education was in part from his close association to Anaxagoras

and Zeno and he learned the arts from all of the growing intelligentsia of that now bustling

city. Recall that democratic Athens allowed any citizen to speak and so oratory and the

powers of persuasion were important skills. Pericles, while apparently not a frequent

speaker, was among the most influential and persuasive of any. Indeed, transcriptions of his

famous funeral oratory at the beginning of the war with Sparta have been read (and

memorized) by students of Classics and History for millennia.

He formally entered politics at about the age of 21, and, through a series of legitimate and

maybe not so legitimate political maneuvers became the head of his party and eventually the

rule of the city. During his reign, which lasted decades, he was directly responsible for

solidifying the democratic structure of Athenian politics (not always in the direction of

inclusiveness) and unprecedented patronage of the arts. It is under Pericles' leadership that

the most famous of Greek architecture was commissioned and much of the recognizable

sculpture, theater, medicine, civics, literature, and early scientific thought were literally born

in a modern guise. The Age of Pericles and the Classical Age of Greece are almost

synonymous.

Sculpture

According to classical accounts, the premier sculptor of the day was Phidias, a personal

friend of Pericles. Essentially nothing but written accounts remain of his works, but they

were apparently spectacular and wholly unlike what we today might think of as Greek work.

While accounts attribute many works to him, two stand out as most revered: the Statue of

Zeus at Olympia and Athena Parthenos. Both were commissioned by Pericles from funds

gleaned from the Delian League and Athenian treasury.

What comes to mind when you think of Classical sculpture? Probably a free-standing, white

marble colorless and expressionless nude. That's how we see them, but the reality was much

different. Their sculptures were painted, which of course has not survived in the few

representative original Greek works that we have available, nor in the Roman copies which

dominate the numbers of actual work that we call ``Greek.'' They must have been colorful

and would have been in great numbers all over the new city of Athens in the public squares,

the Agora, the Acropolis, and in private collections. The two colossals of Phidias were

something else altogether. We have only descriptions with which to make impressions, and

let's take the Athenia statue which stood inside of the Parthenon, high on the

Acropolis{\ldots}visible from sea for miles. She stood 40 feet tall and was of ivory, covered

completely in gold. Picture that---an extravagance of the first magnitude, but magnificent

enough to have been repeatedly written about for many centuries. Her whereabouts are

completely unknown, reportedly the statue was dismantled and carried off to Constantinople

during the 3C A.D. (She was represented on coinage and the descriptions are apparently

good enough that reproductions have been made. The most amazing is in the complete

reproduction of the Parthenon in the city of Nashville, which now houses its own Athenia

Parthenos.) The Statue of Zeus was completely destroyed. Again, it was an enormous work,

again lavishly covered in gold and praised to the extent of being considered one of the Seven

Wonders of the World, a list compiled during the 2C B.C.

Classical Greek sculpture evolved at a rapid pace into what became a representation of the

human body in its most perfect form. As we'll see, this way of thinking was characteristic of

the times and, while likenesses of living people were done as well, the preferred form was

that of the Ideal. The watchwords of all of Classical art seem to be ``balance'' and

``harmony.'' And, in complete contrast to Greek politics and their war-like natures, ``nothing

in excess'' (carved at the Delphi shrine) was the motto, if not an unlikely outcome.

[figures: the charioteer and Poseidon and Discobolous]

Figures XXX and XXXX show two famous representatives of the evolving art form. Notice

a number of things, the first of which is structural. These were free-standing, without the aid

of unnatural marble supports. The balance that was inherent in the spirit of these works is

essential in order that they remain upright. This must have been a focused effort on the part

of the artisans and represents a significant engineering feat. We'll see that this skill will be

lost, and only slowly regained in the early Renaissance. It would have required a studied

blending of engineering sense, exactly the right material, and sophisticated technique to have

produced the //Poseidon// structure. Arms extended, feet far apart{\ldots}everything all in a

vertical plane with the center of gravity squarely above an evenly distributed weight on two

legs. Just like a conscious human adult. Notice also that, as fitting a god, the physique of

//Poseidon// is perfectly symmetric, left-right perfection. This is the characteristic feature of

Classical form: perfection that is wholly unnatural and unrealistic.

The //Discobolous// (//Disc Thrower//) is by an identified artist, ``Myron.'' While celebrating

a ``regular'' human, and not a member of the deity, it too is unnatural in its perfect form, a

demonstration that the rules extended to most, if not all, subjects. These are not individuals,

but classes or //ideas// of individuals. Myron is doing something important in this work. He's

managed to now represent motion in a yet static, and balanced manner. Notice that he

needed to ``cheat'' in order to stabilize the structure, with a post behind the athlete's left leg.

Notice also that he is quoting the Egyptian manner: the //Discobolous// is presenting the

classical Egyptian profile-and-frontal pose, but in an activity in which it's conceivable. With

the Egyptian paintings, such a pose is strange, but in the act of throwing a disc, it's

conceivable.

Classical Greek sculpture is respected for its originality---risk-taking and inventiveness was

prized and rewarded and the competition that this spirit must have spawned led to the

progress which is so evident during the first half of the 5C. However, as an actual style

began to emerge, so did the ``rules'' for what constituted correct form. The ``book'' was

literally written around 440 B.C. by the sculptor Polycleitus. The ``Kanon'' (or Canon)

specified the exact proportions which should govern all human form.

[figure Doryphorus]

His //Doryphorus// shows precisely what these rules included: the head is 1/8 of the total

height, the crown to eyebrow is 3/8 of the head, the eyebrow to chin distance is 5/8 of the

head, and so on. It is a formula for perfection, the very definition of what constitutes the

perfect human form.

Architecture

The Parthenon stands today a shell, but until it was bombed by the Venetians attacked

Athens in 1687, it stood for a millennium as a temple to Athenia, the patroness deity for

Athens, and then as a Christian church during the Byzantine times and when the city fell to

the Ottomans in the mid-15C, as mosque. Today it is a testimony to its chief designer, the

sculptor (and personal friend of Pericles), Phidias, and to techniques which are remarkably

well-thought out.

\chapter{Aristotle}

\label{aristotle}

\chapter{Ptolemy and the Legacy of Greek Astronomy}

\label{ptolemyandthelegacyofgreekastronomy}

%% An example of a body-quotation

%%========= example of quote ==================================

%\begin{quote}

%\textsf{\footnotesize {}

%``A simple example would be the proposition

%that there are mountains on the other side of the moon. No rocket

%has yet enabled me to check this, but I know it to be decidable by

%observation. Therefore this proposition is verifiable in principle

%and is accordingly significant. On the other hand with such metaphysics

%as \char`\"{}the Absolute enters into, but is itself incapable of,

%evolution and progress\char`\"{} {[}F.H. Bradley] one cannot conceive

%of an observation which would determine whether the Absolute did or

%did not enter into evolution; the utterance has no literal significance.''

%}{\footnotesize \par}

%\end{quote}

%%========= example of quote ==================================

%%========= example of sidenote ==================================

%\sidenote{

%There is a particularly poignant story of a slightly older and more established

mathematician named Gottlob Frege who was similarly pursuing a logical derivation of

mathematics. Russell's discovery of the paradox ruined Frege's life work. In reply to

Russell's respectful letter informing him of the difficulty, Frege wrote back, ``Your

discovery of the contradiction has surprised me beyond words, and I should like to say, left

me thunderstruck because it has rocked the ground on which I meant to build arithmetic...I

must give some further thought to the matter.'' Later, Russell took pains to highlight Frege's

many contributions to mathematics, but the older man never was able to rebuild his system

in light of the Russell Paradox.

%}

%%========= example of sidenote ==================================

%

%% An example of a box

%%========= example of box ==================================

%\begin{figure*}

%\begin{boxer}{Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)}

%First paragraph of box.

%\noindent More words.

%\end{boxer}

%\end{figure*}

%%========= example of box ==================================

%% An example of another box

%%========= example of another box ==================================

%\begin{table*}[!t]

%\label{box:mathematics}\vspace{0.5cm}

%\begin{boxer}{Geometry, late 1800's}

%The late 19th century was

%\indent In 1853 in a career-making move,

%\end{boxer}

%\end{table*}

%%========= example of another box ==================================

%% An example of a marginal figure

%%========= example of marg ==================================

%\marg{

%\fig{LadiesInBlue.jpg}{

%Bertrand Russell shortly after being released from his five month prison sentence for his

vocal oppossion to Britain's participation in WWI.%

%\label{cap:russell_40}}

%}

%%========= example of marg ==================================