* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Left-Sided Heart Failure

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Mitral insufficiency wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

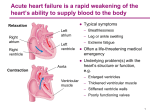

Heart failure: is a syndrome that occurs as a result of the progressive inability of the heart to pump enough blood to meet the body’s oxygen and nutrient needs. It can cause decreased tissue perfusion, fatigue, fluid volume overload in the intravascular and interstitial spaces, and reduced quality and length of life. Pathophysiology: The heart is divided into two separate pumping systems. The right side of the heart forms one pump. The left side of the heart forms the other pump. Normally these pumps work together to ensure that equal amounts of blood enter and leave the heart. Blood flow through the heart begins in the right atrium. Un-oxygenated blood from the body’s venous system enters the right atrium from the inferior and superior venae cavae. Next the blood enters the right ventricle to be pumped into the pulmonary artery and into the lungs for oxygenation. After receiving oxygen in the lungs, the blood is returned to the left atrium via the four pulmonary veins. The oxygenated blood then enters the left ventricle and is pumped out into the aorta and the systemic circulation. Proper cardiac functioning requires each ventricle to pump out equal amounts of blood over time. If the amount of blood returned to the heart becomes more than either ventricle can handle, the heart can no longer be an effective pump. Conditions that cause heart failure may affect one or both of the heart’s pumping systems. Therefore heart failure can be classified as right-sided heart failure, left-sided heart failure, or biventricular heart failure. The ventricle is the area of the heart’s pumping system that commonly fails. Of the two ventricles, the left ventricle is typically the one to weaken first because it has the greatest workload. The right and left sides of the heart’s pumping system work together in a closed system to continuously move blood forward, so failure of one side eventually leads to failure of the other side. Left-Sided Heart Failure: A certain amount of force must be generated by the left ventricle during a contraction to eject blood into the aorta through the aortic valve. This force is referred to as afterload. The pressure within the aorta and arteries influences the force needed to open the aortic valve to pump blood into the aorta. This pressure is called peripheral vascular resistance (PVR). Hypertension is one of the major causes of left-sided heart failure because it increases the pressure within arteries. Increased pressure in the aorta makes the left ventricle work harder to pump blood into the aorta. Over time the strain caused by the increased workload causes the left ventricle to weaken and fail. Other conditions that can lead to left-sided heart failure. Among these conditions are disorders that: (1) Restrict the outflow of blood from the left ventricle, as in aortic valve stenosis or coarctation of the aorta, which is a malformation causing narrowing; (2) Impair contractility of the heart, as in myocardial infarction or cardiomyopathy; and (3) Allow blood to flow backward into the left atrium, as in valvular disorders. With left-sided heart failure, blood backs up from the left ventricle into the left atrium and then into the four pulmonary veins and lungs This increases pulmonary pressure, causing movement of fluid first into the interstitium and then the alveoli. Alveolar edema is more serious because it reduces gas exchange across the alveolar capillary membrane. Shortness of breath and cyanosis may result from the decreased oxygenation of the blood leaving the lungs. If the fluid buildup is severe, pulmonary edema occurs, which requires immediate medical treatment. Right-Sided Heart Failure: Causes of right-sided heart failure. The major cause of right-sided heart failure is left sided heart failure. When the left side fails, fluid backs up into the lungs and pulmonary pressure is increased. The right ventricle must continually pump blood against this increased fluid and pressure in the pulmonary artery and lungs. Over time this additional strain eventually causes it to fail. Conditions causing right-sided heart failure increase the work of the right ventricle. They increase the amount of contractile force needed or they require pumping of excess blood volume (preload). Among these conditions are disorders that: (1) Increase pulmonary pressures, such as emphysema or congenital heart defects; (2) Restrict the outflow of blood from the right ventricle, as in pulmonary valve stenosis. (3) Allow left atrial blood to flow into the right atrium, thereby increasing blood volume in the right ventricle, as in septal defects. When the right ventricle hypertrophies or fails because of increased pulmonary pressures, it is referred to as cor pulmonale. When the right ventricle fails, it does not empty normally and there is a backward buildup of blood in the systemic blood vessels. As the blood backs up from the right ventricle, right atrial and systemic venous blood volume increases. The jugular neck veins, which are not normally visible, become distended and can be seen when the person is in a 45-degree upright position. Edema may occur in the peripheral tissues, and the abdominal organs can become engorged. Congestion in the gastrointestinal tract causes anorexia, nausea, and abdominal pain. As the failure progresses, blood pools in the hepatic veins and the liver becomes congested, known as hepatomegaly. Pain in the right upper quadrant and impaired liver function are caused by this liver congestion. Systemic venous congestion also leads to engorgement of the spleen, known as splenomegaly. Compensatory Mechanisms to Maintain Cardiac Output: Compensatory mechanisms help ensure that an adequate amount of blood is being pumped out of the heart. Although these mechanisms are designed to maintain cardiac output, they can also contribute to heart failure and create a cycle that instead of being helpful leads to further heart failure. When the sympathetic nervous system detects low cardiac output, it speeds up the heart rate by releasing epinephrine and norepinephrine. Although this raises cardiac output (cardiac output=heart rate*stroke volume), the increased heart rate also increases the oxygen needs of the heart. In response to low renal blood flow, the kidneys activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and antidiuretic hormone is released from the pituitary gland to conserve water, causing decreased urine output. This adds to the fluid retention problem already found in heart failure. Over time the heart responds to the increased workload by enlarging its chambers (dilation) and increasing its muscle mass (hypertrophy). In dilation the heart muscle fibers stretch to increase the force of myocardial contractions, which is known as the Frank-Starling phenomenon. In hypertrophy the muscle mass of the heart increases, creating more contractile force. Both these compensatory mechanisms also increase the heart’s oxygen needs. Causes and Signs and Symptoms of Heart Failure: items Left Side Failure Right-Sided failure Causes Signs and Symptoms Hypertension: Resistance increased from elevated pressure. Coarctation of the aorta: Resistance increased from elevated pressure. Myocardial infarction: Increased workload from poor contractility. Cardiomyopathy: Increased workload from poor contractility. Aortic stenosis: Increased volume to pump. Mitral regurgitation: Increased volume to pump. • • • • • • • • • Dyspnea Dry cough Crackles, wheezing Orthopnea Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea Cyanosis Fatigue, weakness Tachycardia Nocturia Pulmonary hypertension: Resistance increased from elevated pressure. Cor pulmonale: Resistance increased from elevated pressure. Pulmonary stenosis: Increased volume to pump. Atrial septal defect: Increased volume to pump. • • • • • • • • • • Jugular vein distension Dependent peripheral edema Ascites Weight gain Splenomegaly Hepatomegaly GI discomfort Fatigue, weakness Tachycardia Nocturia Diagnostic Tests:• History and physical examination. • A chest x-ray examination shows the size, shape, and enlargement of the heart and congestion in the pulmonary vessels. • Electrocardiogram: Cardiac dysrhythmias that precipitate and contribute to heart failure can be diagnosed with electrocardiogram. Chamber enlargement in the atrium from heart failure is shown by P-wave changes and in the left ventricle by increased voltage and deeper S waves in some V leads. • Exercise stress testing and nuclear imaging studies: provide information on activity tolerance, which is usually limited in heart failure. • Echocardiography: measures the size of the heart chambers to detect enlargement and assess valvular function and motion of the ventricles. • Cardiac catheterization and angiography: are used to detect underlying heart disease that may be the cause of heart failure. • Hemodynamic monitoring: Direct assessment of the heart’s pressures is done with hemodynamic monitoring. A catheter is inserted into the heart and pulmonary artery to transmit pressures to a cardiac monitor. These cardiac and pulmonary pressures are then used to guide medical therapy. • Serum laboratory tests: may show elevated serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and elevated serum creatinine from renal failure and elevated liver enzymes from liver damage. Complications: Liver and spleen enlarge from the fluid congestion, which causes impaired function, cellular death, and scarring. Pleural effusion, a leakage of fluid from the capillaries of the lung into the pleural space, can occur. The elevated pressures in the capillaries of the lung cause this leakage. Thrombosis and emboli can occur as a result of poor emptying of the ventricles, which leads to stasis of blood. Aspirin or anticoagulants are often prescribed to prevent thrombus formation in patients with heart failure. Cardiogenic shock, often caused by a myocardial infarction that damages the left ventricle, occurs when the left ventricle is unable to supply the tissues with enough oxygen and nutrients to meet their needs. Cardiogenic shock is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate treatment. Medical Treatment:The overall goal of medical treatment for chronic heart failure is to improve the heart’s pumping ability and decrease the heart’s oxygen demands. Treatment of heart failure focuses on (1) Identifying and correcting the underlying cause, (2) Increasing the strength of the heart’s contraction, (3) Maintaining optimum water and sodium balance, and (4) Decreasing the heart’s workload. The medical treatment divided to two parts: Part one: • Non Invasive Oxygen Therapy: One of the major problems caused by heart failure is a reduction in oxygen delivered to the tissues. The heart failure signs and symptoms of this are fatigue, dyspnea, altered mental status, and cyanosis. Oxygen therapy assists in supplying the oxygen needs of the tissues. In mild heart failure, oxygen may be delivered via nasal cannula. For more severe cases, arterial blood gas values guide oxygen delivery, either via masks that provide high concentrations of oxygen or with mechanical ventilation. Activity: Activity tolerance depends on the severity of heart failure signs and symptoms. Severe symptoms may require bedrest with restricted activity until treatment reduces the symptoms. For stable heart failure, a regular exercise program can be helpful in improving cardiac function and reducing heart failure effects. Patients should be encouraged to stay as active as possible within the parameters the physician has prescribed. An individualized walking program that increases activity over time is often prescribed. Patients should be taught how to exercise safely without causing symptoms and to understand that overexertion can produce fatigue the next day. Referral to a cardiac rehabilitation program can be helpful. Nutrition: Dietary sodium is often restricted to decrease fluid retention. Restricting sodium is challenging. Compliance is often low because low sodium foods are not very appealing. A referral to a dietitian is important. Diet counseling helps the patient and family understand the need for dietary compliance and the need to provide menus that are appealing and easy to use. Salt substitutes often use potassium in place of sodium, so the patient and physician should discuss their use. Spices, herbs, and lemon juice may be suggested to flavor unsalted foods. Eating should remain pleasurable for the patient to avoid malnutrition. Focus on showing patients the foods that they like and can still have rather than talking about only the foods they cannot have. Drug Therapy: The major classifications of oral drugs used to treat heart failure are listed • ACE Inhibitors Left • Diuretic • Beta blockers • Inotropic agents • Aldosterone antagonist • Anticoagulants • Antidysrhythmic agents Management of heart failure is a balancing act. Part two: Invasive • Synchronizing pacemaker • Mechanical assistive devices: • Intra-aortic balloon pump. • Left ventricular assist device. • Total artificial heart. • Surgery: • Cardiomyoplasty. • Cardiac transplant. Intra-aortic balloon pump. Nursing Process for Heart Failure: Nursing Assessment: A nursing history and physical examination are done to gather subjective and objective data. While obtaining data, focus on areas that might indicate the presence of heart failure. Subjective Data: Respiratory: - Lung disease? How many flights of stairs can be climbed without dyspnea? How many pillows used for sleeping? Dyspnea at rest or that awakens from sleeping? Cardiovascular: - Any cardiac disease history: hypertension, myocardial infarction, valvular problem, anemia, dysrhythmias, Palpitations Chest pain—precipitating factors, severity, relieving factors, Can activities of daily living be performed? Can activities performed 6 months, 4 months, 2 months, 2 weeks ago still be done? Any dizziness (vertigo) or fainting (syncope)? Fluid retention: - Daily sodium intake? Weight gain? Are shoes tight? Do ankles swell? Gastrointestinal is appetite good? Any nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain? Urinary: - Decrease in daytime urine output? How often does patient go to the bathroom at night (nocturia)? Neurological: - Any change in behavior? Medications. Knowledge of condition. Coping skills. Objective Data: Respiratory Tachypnea, crackles, wheezing, respiratory effort, dyspnea with exertion Cardiovascular Tachycardia, dysrhythmias, jugular vein distention, peripheral edema—degree of pitting Gastrointestinal Abdominal distention, ascites, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly Neurological Confusion, decreased level of consciousness, restlessness, impaired memory Integumentary Cold, clammy skin; pallor; cyanosis General Weight Diagnostic test findings Nursing Diagnoses: • Activity intolerance (or risk for activity intolerance) related to imbalance between oxygen supply and demand because of decreased CO. • Excess fluid volume related to excess fluid or sodium intake and retention of fluid because of HF and its medical therapy. • Anxiety related to breathlessness and restlessness from inadequate Oxygenation. • Powerlessness related to inability to perform role responsibilities because of chronic illness and hospitalizations. • Noncompliance related to lack of knowledge. Planning and Goals: Major goals for the patient may include promoting activity and reducing fatigue, relieving fluid overload symptoms, decreasing the incidence of anxiety or increasing the patient's ability to manage anxiety, teaching the patient about the self-care program, and encouraging the patient to verbalize his or her ability to make decisions and influence outcomes. Nursing Interventions: Promoting Activity Tolerance 1- The nurse and patient can collaborate to develop a schedule that promotes pacing and prioritization of activities. The schedule should alternate activities with periods of rest and avoid having two significant energy-consuming activities occur on the same day or in immediate succession. 2- Because some patients may be severely debilitated, they may need to perform physical activities only 3 to 5 minutes at a time, one to four times per day. The patient then should be advised to increase the duration of the activity, then the frequency, before increasing the intensity of the activity (Meyer, 2001). 3- Barriers to performing an activity are identified, and methods of adjusting an activity to ensure pacing but still accomplish the task are discussed. For example, objects that need to be taken upstairs can be put in a basket at the bottom of the stairs throughout the day. At the end of the day, the person can carry the objects up the stairs all at once. Likewise, the person can carry cleaning supplies around in a basket or backpack rather than walk back and forth to obtain the items. 4- Small, frequent meals decrease the amount of energy needed for digestion while providing adequate nutrition. The nurse helps the patient to identify peak and low periods of energy and plan energy-consuming activities for peak periods. For example, the person may prepare the meals for the entire day in the morning. Pacing and prioritizing activities help maintain the patient’s energy to allow participation in regular physical activity. 5- The patient’s response to activities needs to be monitored. If the patient is hospitalized, vital signs and oxygen saturation level are monitored before, during, and immediately after an activity to identify whether they are within the desired range. Heart rate should return to baseline within 3 minutes. 6- If the patient is at home, the degree of fatigue felt after the activity can be used as assessment of the response. If the patient tolerates the activity, short-term and long-term goals can be developed to gradually increase the intensity, duration, and frequency of activity. 7- Referral to a cardiac rehabilitation program may be needed, especially for HF patients with recent myocardial infarction, recent open-heart surgery, or increased anxiety. A supervised program may also benefit those who need the structured environment, significant educational support, regular encouragement, and interpersonal contact. Managing Fluid Volume 1- Patients with severe HF may receive intravenous diuretic therapy, but patients with less severe symptoms may receive oral diuretic medication. Oral diuretics should be administered early in the morning so that diuresis does not interfere with the patient’s nighttime rest. 2- Discussing the timing of medication administration is especially important for patients, such as elderly people, who may have urinary urgency or incontinence. A single dose of a diuretic may cause the patient to excrete a large volume of fluid shortly after administration. 3- The nurse monitors the patient’s fluid status closely— auscultating the lungs, monitoring daily body weights, and assisting the patient to adhere to a lowsodium diet by reading food labels and avoiding high-sodium foods such as canned, processed, and convenience foods. 4- If the diet includes fluid restriction, the nurse can assist the patient to plan the fluid intake throughout the day while respecting the patient’s dietary preferences. If the patient is receiving intravenous fluids, the amount of fluid needs to be monitored closely, and the physician or pharmacist can be consulted about the possibility of maximizing the amount of medication in the same amount of intravenous fluid (eg, double-concentrating to decrease the fluid volume administered). 5- The nurse positions the patient or teaches the patient how to assume a position that shifts fluid away from the heart. The number of pillows may be increased, the head of the bed may be elevated (20- to 30-cm [8- to 10-inch] blocks may be used), or the patient may sit in a comfortable armchair. In this position, the venous return to the heart (preload) is reduced, pulmonary congestion is alleviated, and impingement of the liver on the diaphragm is minimized. The lower arms are supported with pillows to eliminate the fatigue caused by the constant pull of their weight on the shoulder muscles. 6- The patient who can breathe only in the upright position may sit on the side of the bed with the feet supported on a chair, the head and arms resting on an overbed table, and the lumbosacral spine supported by a pillow. If pulmonary congestion is present, positioning the patient in an armchair is advantageous, because this position favors the shift of fluid away from the lungs. Controlling Anxiety 1- Because patients in HF have difficulty maintaining adequate oxygenation, they are likely to be restless and anxious and feel overwhelmed by breathlessness. These symptoms tend to intensify at night. 2- Emotional stress stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, which causes vasoconstriction, elevated arterial pressure, and increased heart rate. This sympathetic response increases the amount of work that the heart has to do. By decreasing anxiety, the patient’s cardiac work also is decreased. Oxygen may be administered during an acute event to diminish the work of breathing and to increase the patient’s comfort. 3- When the patient exhibits anxiety, the nurse takes steps to promote physical comfort and psychological support. In many cases, a family member’s presence provides reassurance. 4- To help decrease the patient’s anxiety, the nurse should speak in a slow,calm, and confident manner and maintain eye contact. When necessary, the nurse should also state specific, brief directions for an activity. 5- After the patient is comfortable, the nurse can begin teaching ways to control anxiety and to avoid anxiety-provoking situations. The nurse explains how to use relaxation techniques and assists the patient to identify factors that contribute to anxiety. Lack of sleep may increase anxiety, which may prevent adequate rest. 6- Other contributing factors may include misinformation, lack of information, or poor nutritional status. Promoting physical comfort, providing accurate information, and teaching the patient to perform relaxation techniques and to avoid anxiety triggering situations may relax the patient. 7- In cases of confusion and anxiety reactions that affect the patient's safety, the use of restraints should be avoided. Restraints are likely to be resisted, and resistance inevitably increases the cardiac workload. The patient who insists on getting out of bed at night can be seated comfortably in an armchair. As cerebral and systemic circulation improves, the degree of anxiety decreases, and the quality of sleep improves. Minimizing Powerlessness 1- The nurse assesses for factors contributing to a sense of powerlessness and intervenes accordingly. Contributing factors may include lack of knowledge and lack of opportunities to make decisions, particularly if health care providers and family members behave in maternalistic or paternalistic ways. 2- If the patient is hospitalized, hospital policies may promote standardization and limit the patient’s ability to make decisions (eg, what time to have meals, take medications, prepare for bed). 3- Taking time to listen actively to patients often encourages them to express their concerns and ask questions. 4- Other strategies include providing the patient with decision-making opportunities, such as when activities are to occur or where objects are to be placed, and increasing the frequency and significance of those opportunities over time; providing encouragement while identifying the patient’s progress; and assisting the patient to differentiate betweenfactors that can be controlled and those that cannot. 5- In some cases, the nurse may want to review hospital policies and standards that tend to promote powerlessness and advocate for their elimination or change (eg, limited visiting hours, prohibition of foodfrom home, required wearing of hospital gowns). Evaluation Expected Patient Outcomes Expected Patient Outcomes May Include: 1. Demonstrates tolerance for increased activity: a. Describes adaptive methods for usual activities. b. Stops any activity that causes symptoms of intolerance. c. Maintains vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse). d. Identifies factors that contribute to activity intolerance. e. Establishes priorities for activities. f. Schedules activities to conserve energy and to reduce fatigue and dyspnea. 2. Maintains fluid balance: a. Exhibits decreased peripheral and sacral edema. b. Demonstrates methods for preventing edema. 3. Is less anxious: a. Avoids situations that produce stress. b. Sleeps comfortably at night. c. Reports decreased stress and anxiety. 4. Makes decisions regarding care and treatment: a. States ability to influence outcomes. 5. Adheres to self-care regimen. a. Performs and records daily weights. b. Ensures dietary intake includes no more than 2 to 3 g of sodium per day. c. Takes medications as prescribed. d. Reports any unusual symptoms or side effects.