* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download THIS FILE GENERATED BY THE FUND LIBRARY. (c) The Fund

Private equity secondary market wikipedia , lookup

Mark-to-market accounting wikipedia , lookup

Money market fund wikipedia , lookup

Fund governance wikipedia , lookup

Private money investing wikipedia , lookup

Socially responsible investing wikipedia , lookup

Mutual fund wikipedia , lookup

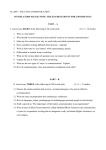

THIS FILE GENERATED BY THE FUND LIBRARY. (c) The Fund Library Inc. Data supplied by Fundata Canada Inc. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Feature article ------------------------------------------------------------------------------The Best Mutual Fund Manager of all Time: Peter Cundill By Mackenzie Financial Corp. Tuesday, May 21, 2002 The Invisible Hand Incarnate: Peter Cundill It's December 5th, the day of the Canadian Mutual Fund Awards Gala. The Canadian room at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto is teeming with Bay Street's finest, decked out in full black tie attire. All 600-plus attendees are keyed in on the front stage. Fund guru, Steve Kangas steps up to the podium to announce the highlight of the night: the winner of the Analysts' Choice Career Achievement Award. It's the Indiana Jones of Canadian money managers. Out from the audience, a man with a shiny bald head comes bounding on spry legs that belie his 63 years. Peter Cundill is the man of the hour, the night, and the last 25 years. In fitting fashion, the dapper fund manager punctuates the thank you speech with the unexpected, pulling his black rimmed glasses from his breast pocket, Cundill breaks into a poem he has composed for the occasion. But hark Listen to the clarion call Duty and trust Excitement and risk Comradeship and challenge But above all change We all of us have moments in the sun And moments in the shade No fortunes are made in prosperity Ours is a marathon without end Enjoy the passing moments Q.Who is Peter Cundill?A. The greatest mutual fund manager of all time.Steve Kangas who knows the annals of Canadian mutual fund industry like the back of his hand calls Peter Cundill the greatest mutual fund manager of all time. Charles Brandes and Sir John Templeton rank not far behind, but they fall short of the profession's pinnacle. What about Warren Buffett or George Soros? Neither of them are mutual fund managers. There are many fund managers with a 17 percent 1, 3 or even 5-year record. But how many managers can lay claim to having made 17 per cent annualized over the past 25 years? In the entire world, Peter Cundill is the only mutual fund manager who can raise his hand. Two days before Halloween in 1938, at the tail-end of the worst depression the world of modern capitalism had seen, Peter Cundill was born in Montreal. Peter was born with the stock market in his blood. His father was a floor trader on the Montreal and Canadian Stock exchanges for 40 years and his Uncle was a Chairman at Wood Gundy. Peter attended grade school up until 6th grade with David Bissett, whom would later be the founding officer Bissett Investment Management. Peter's father encouraged him to become a chartered accountant because as he said, "If you're a gambler like I am, you'll need a trade to fall back on if you blow the stock market." Peter obliged his father, graduating from McGill with a Bachelor of Commerce Degree (a path Captain Kirk would follow). After his BComm, Peter commenced the beginning of the sixties with a cup of coffee in the European financial scene, working at Morgan Guaranty Trust Co. in Paris, and then Wood Gundy & Company Ltd. in London. Shortly thereafter, Peter made good on his father's wish, earning his colours in the accounting profession with a CA in 1963. But the drab world of accounting was not for Peter. The allure of greasing the wheels of capitalism as an investment manager was too much to resist.Adopting the bottom-up value philosophy of Benjamin Graham with the meticulous tenacity of a brighteyed accountant, Cundill quickly rose through the investment ranks. He worked in the Corporate Finance Dept. at Greenshields Inc. in Montreal, then over to the west coast in Vancouver at the Yorkshire Group until 1972.In the mid-seventies, the Canadian mutual fund industry was in disarray. Assets under management were a $2b compared to over $400b today, and there were about 63 mutual funds in Canada compared to well over 4,000 today. To become President of AGF Vancouver Investment Management Ltd.Cundill "had to go to Top Emory who was Chairman of IFIC." Cundill stepped into his office "Top, I have to tell you, there are two investigations for fraud in both parts of the [AGF] operations in Vancouver and Toronto. I did not make his day. He did not thank me for showing up in his office. Although we dealt with the problems." Shortly thereafter Cundill, with AGF Chairman, Warren Goldring's support, became President of AGF Vancouver Investment Management Ltd.In 1975, after almost 15 years of working for "the man", Cundill took the plunge and started up his own Company, The Cundill Value Fund Ltd, of whom John Templeton was the largest shareholder. By 1985, Cundill was making enough money to be convinced of the benefits of abandoning his frigid home and native land for the balmy tax haven of Bermuda. The sun has not gone to Mr. Cundill's head. His original Cundill Value Fund (now known as Mackenzie Cundill Value Series A) started in December 1974 is running an inception rate of return of 16.7 per cent as of February 28th. A $10,000 investment in Cundill's fund on January 1st 1975 would be worth over $655,000 today. Most other mutual fund managers would be dancing in the streets with such a number. Not Cundill. He thinks it is lower than it should be, because his big bets-although he wouldn't use that term-in Japan are taking longer to pay off than he had hoped.The boys at Mackenzie Financial recognized Cundill's confounding knack for churning out steady returns year after year, and in October 1998 decided to place the ring on Cundill's finger. The proposal: marry Mackenzie's marketing expertise with Cundill's management expertise. A win-win situation. Cundill was a willing bride, and now he manages about $1.3b in his namesake funds for Mackenzie along with another $1b in his capacity as 1/5 of the team that manages the $5.2b of investors' money in the Mackenzie Universal Select Managers and its RSP counterpart. Sometimes the greatest thing about a cushion is that it gives you the means to ensure that it is never needed. In this age, in which Bay and Wall Street are often accurately compared to Las Vegas, Peter Cundill stands in contrast as the antithesis of the stock-picker gambler. He doesn't pretend to know when to "hold em" and when to "fold em". He simply buys dollar bills when they are priced at 50 cents, and waits for the market to catch up. How he does it?"Who says you can't join value and growth at the hip."Peter Cundill, December 5th, 2002, TorontoIn 1995, the Financial Times of London profiled Peter Cundill as one of Ten Living Legends in the Global Guide to Investing. In his 27 years as a money manager, Cundill has had only two down years. What's his secret? If you boil it down, there are five ingredients to Cundill's investing success.Balance Sheet Security BlanketFirst and foremost, the balance sheet is Peter Cundill's best friend. Unlike Warren Buffett, Cundill looks to the balance sheet as his security blanket and does not stray. He is a Ben Graham purist. Cundill screens tens of thousands of stocks to see which ones meet his quantitative standards. "We look for a margin of safety in the balance sheet as distinct from the business." He keys in on two things. Cundill likes companies that are trading at a discount to what their net assets are worth. He seeks out misunderstood and out-of fashion securities. When a company has a "net-net" (current assets minus current liabilities, long-term debt, and lease and pension fund liabilities) that is greater than the share price--that is solid value play. "We try to buy a dollar bill for 50 cents in whatever form that dollar bill takes," Cundill says.The other area Cundill keys in on is what was coined by Norman Weinger formerly of Oppenheimer as the "magic sixes". The seesaw of values is represented by three groups of ratios. Merlin-like companies that can cast the potent combination of having a six per cent dividend yield, a price-to-earnings ratio of 6, and stock that is trading at 60 per cent of book value, are undervalued and merit serious attention. Four is fair. A stock that has a 4 per cent dividend yield, a price-toearnings ratio of 14, and is trading at 140 per cent of book value, is fairly valued. Then there are the nasty sixes. A stock that has a 0.6 per cent dividend yield, a price-to-earnings ratio of 60, and is trading at 600 per cent of book value, is overvalued and might suggest a shorting opportunity. The magic sixes don't often make for a pretty basket of stocks. As Kangas puts it, "if you look at Cundill's top-ten holdings you wouldn't want to own a single one of them. But the returns are there. He is just one of those guys where you have to close your eyes and hang on for the ride."Stocks with StoriesThe triple magic six combination can turn in a heavenly return on its own. Cundill prefers to follow his Father's advice which was, "never shoot into the brown." He meant you should never shoot into a flock of birds without first choosing a single bird-at least in your mind. Know what the companies do as well. This is Cundill's specialty. He looks for a few keywords not usually associated with investment opportunity. Words such as "riot", "investing nightmare", or "quagmire" perk him up. After Cundill does the quant screen, he looks for stocks with stories. One of his early investments was in Mississippi Municipal Bonds that were originally issued prior to the American War of Independence, and then subsequently reneged on. Cundill bought the bonds at a huge discount, and then was a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the State of Mississippi. The bonds since jumped in value, allowing Cundill to take a hefty profit, but he kept a few. Partly for souvenir (one hangs on his office wall in London) and partly in case the litigation ends, which will likely push the value of the bonds up further. In 1995, people were rioting in the streets in Paris. Cundill's ears perked up. Investors were shunning France. He swooped in to make BNP Paribas the largest position in the Cundill Value fund. "People in France were throwing fire bombs and striking. And that usually is a good time-although of course it's not always-to buy securities." He bought the shares in the company at an average price of 270 francs a share, or about paying 60% of the net asset value (NAV) and 5 times potential earnings.Another story Cundill likes to recount is a stock he bought in 1985, Tachihi Enterprise - formerly named Tachikawa Aircraft - which made planes during the Second World War in which Kamikaze pilots went off to their glory. "The company just happened to sit on 225 acres of green land 35 miles west of Tokyo. And as you may imagine, there isn't a whole lot of green land within 35 miles of Tokyo. They had no debt, and they were working on getting approvals to develop their land. If you took the value of the land, Tachihi's real estate alone would make its shares worth Y13,000 each." He bought it for Y2,500, and sold it six months later for Y4,600. Regardless of the returns, Cundill has made from investing in the riots, pre-civil war state bonds, and a Kamikaze plane manufacturer, all three investments make great cocktail party stories.The FloaterBeside the ratios and stock stories, Cundill is a tireless global networker, traveling the seven seas 200 days a year in his various capacities as Chair of the club of global elites, the Aspen Institute, and as what he describes himself as the designated "floater" for the Cundill funds. He counts his friends among the highest rungs of the world's political, and business ladder. The dense forest of power and knowledge helps him to get an inside edge on potential bargains whether it be from insights into a particular country or a company. Short workMost investors don't understand the extent that some mutual fund managers use shorting strategies to capitalize when the markets are overvalued. Peter Cundill is a big shorter. In a March 20, 1996 memo titled The Almost Definitive Memo on Our Short Positons, Cundill wrote to his team: "Be short 50% of the invested portfolio using US Futures and Options. As or if markets go up, increase the short positions. This will be a judgment matter." Cundill's reasoning: out of 10,000 North American stocks screened, only 41 were trading at fair value. The market was obviously overvalued. The see saw of value was set for a swing downward. He wrote words that he agrees apply today to US market: "Valuations are moving towards extremes. This market is dominated by reckless responsibility."(Fundlibrary editor's note: Mr. Cundill cannot short stocks in the conventional mutual funds offered through Mackenzie Financial)He cautioned that overvaluation was not enough to tip the see saw the other way. "Over-valuation itself is not enough. You need at least one other factor. A lack of liquidity is the most important determinate for a decline." Cundill also made money shorting the Nikkei in 1992, and 1993, and later in the nineties he was short the Internet Index. But he cautioned in his memo: "Over the last century, share markets have gone up 70% of the time. You must have significant overvaluation to justify being short." Cundill believes that the present US equity picture is presently "significantly overvalued."Factors that influence the markets according to Peter CundillInterest rates Economic currency activity movements Value Political environment Perceptions about the market Inflation Liquidity The TeamOr course, Peter Cundill is not a one-man show. His core team is buttressed with four people in particular that continue to hold up the reputation and philosophy of the Cundill namesake funds: Brian McDermott, Tim McElvaine, Alan Pasnik on the income side and David Briggs on the Asian side. Why Japan?Japan's banks are overexposed. The Nikkei 225 closed below the Dow Jones Industrial Average for the first time in 45 years. Standard & Poor's chief credit officer said that Japanese banks were "technically insolvent", barely creating a stir and showing just how far the sun has set on Japan. 70% of Japan's firms lost money last year. There is a credit crunch. To top it off, Japan is facing a demographic crisis that according to David Foot, co-author of Boom, Bust and Echo, will finish Japan off. Even sushi-loving investors won't touch Japan with a ten-foot pole. That's just the kind backdrop Peter Cundill loves.50 per cent of the Cundill Value Series of funds (A, B, C and Capital Class) are invested in Japan. Cundill knows Japan's roll sheet as well as anyone. He even adds some points, mentioning that Japanese companies have an extremely poor record regarding shareholder rights, noting a quote from Hideo Ishihara, Chair of Goldman Sachs Japan: "I don't know what you're talking about. In a Japanese company, first and foremost comes the employee. Then comes the customer. Third come the bankers and suppliers." But then Cundill goes on the offensive. "That's [the poor corporate respect for shareholders] changing. Relative to reported earnings, Japanese stocks remain very expensive. But on the basis of their asset values, Japanese stocks are really cheap. Cundill visited Japan in 1969, then took a hiatus and has been making regular trips there since 1985. Where most investors see the aging Japanese population as the nail in the coffin of an already beleaguered economy, Cundill sees great promise. "By the year 2025, 42 per cent of Japan will be retired. The Japanese have three choices. They can reduce the pension benefits, but that is unlikely because 42 per cent are a lot of voters. They can tax the young more heavily, but that is difficult because taxes in Japan are already quite high. The only other alternative is to generate a greater return on Japanese pension investments that are running at pitiful levels right now. If they can't up their returns, they are in really big trouble." The mother of innovation is necessity and the Japanese have plenty of that right now. The will is there but where is the way? That comes in two packets: one, Asia is changing greatly with the ascension of China into the WTO ranks, and two, old Japanese people will not be so good at making watches, but they are great marketers and have a culture well suited to being a conduit between China and the west. Cundill says dramatically, "you heard it here first. Japan is going to be the America of Asia." Japan's days as a maker of products are over, its days of moving and marketing them are just beginning. You don't make any money following the crowd, and Cundill is out on his own on this call. Pretty big gamble for a guy who is not a gambler. If he's right, he will go down in the annals of mutual fund history as the greatest there ever was. If he's wrong, he will have to take solace in a long storied career and his American wife and family. Either way, when Peter Cundill takes his final jog into the sunset on the beaches of Bermuda, he will be remembered as the mutual fund industry's marathon man.