* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

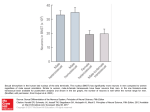

Download clinical practice guidelines for management of sexual dysfunctions

Sexual slavery wikipedia , lookup

Homosexualities: A Study of Diversity Among Men and Women wikipedia , lookup

Adolescent sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Human mating strategies wikipedia , lookup

Sexual assault wikipedia , lookup

Hookup culture wikipedia , lookup

Incest taboo wikipedia , lookup

Human sexual activity wikipedia , lookup

Sexual objectification wikipedia , lookup

Erotic plasticity wikipedia , lookup

Sexual fluidity wikipedia , lookup

Sex and sexuality in speculative fiction wikipedia , lookup

Sexual racism wikipedia , lookup

Sexuality after spinal cord injury wikipedia , lookup

Age of consent wikipedia , lookup

Heterosexuality wikipedia , lookup

Ages of consent in South America wikipedia , lookup

Sexual abstinence wikipedia , lookup

Sexual reproduction wikipedia , lookup

Sexual selection wikipedia , lookup

Human male sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Sex in advertising wikipedia , lookup

Sexual addiction wikipedia , lookup

Ego-dystonic sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Sexual stimulation wikipedia , lookup

Human female sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Female promiscuity wikipedia , lookup

Sexological testing wikipedia , lookup

History of human sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Sexual ethics wikipedia , lookup

Slut-shaming wikipedia , lookup

Lesbian sexual practices wikipedia , lookup

Rochdale child sex abuse ring wikipedia , lookup

Penile plethysmograph wikipedia , lookup

Human sexual response cycle wikipedia , lookup