* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS Infective endocarditis is an infection of

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

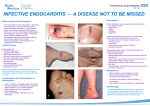

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endocardial surface of the heart. The disease may occur as an acute, fulminating infection, but more commonly runs an insidious course and is known as subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE.) The term 'infective endocarditis' is preferred because not all the infecting organisms are bacteria, and fungi can be responsible. The annual incidence in the UK is 6-7 per 100 000, but it is more common in developing countries. Without treatment the mortality approaches 100% and even with treatment there is a significant morbidity and mortality. Aetiology Endocarditis is usually the consequence of two factors: the presence of organisms in the bloodstream and abnormal cardiac endothelium facilitating their adherence and growth. Factors causing a bacteraemia Anything that results in a breach of the body's innate defences can potentially cause a bacteraemia. In some cases the cause of the bacteraemia is unknown; more often; there is an obvious factor that facilitated the entry of organisms into the bloodstream. This may be patient orientated: poor dental hygiene, intravenous drug use, soft tissue infections; or iatrogenic: dental treatment, intravascular cannulae (especially central), cardiac surgery, or permanent pacemakers. Local cardiac factors Damaged vascular endothelium will promote platelet and fibrin deposition. It is these small thrombi that allow organisms to adhere and grow. As they grow, more fibrin and platelets are deposited, forming the characteristic infected vegetation. Abnormal vascular endothelium can be the result of valvular lesions, which create areas of non-laminar blood flow, or jet lesions resulting from ventricular septal defects or a patent ductus arteriosus. Infective endocarditis is less likely to develop where the haemodynamic disturbance is minimal (i.e. low-pressure systems). Hence it is more common in ventricular septal defects than atrial septal defects, and rare in mitral valve prolapse without significant regurgitation. Aortic and mitral valves are the commonest valves to be affected. Rightsided endocarditis is typically related to intravenous drug use, although the exact pathological mechanisms that underlie this association are not fully known. It may be that damage to right -sided valves results from the injected particulate matter used to cut the drugs. Instrumentation of the right heart (central venous catheter and temporary pacemaker insertion) is also a common cause of right-sided endocarditis. Virulent pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae may adhere and multiply on previously normal valves. Microbiology Over three-quarters of cases are due to streptococci or staphylococci. The viridans group of streptococci (Strep.mitis, Strep. sanguis) are commensals in the upper respiratory . Other organisms, including Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium and Strep. bovis, may enter the blood from the bowel or urinary tract. Staph. aureus has now overtaken streptococci as the most common cause of acute endocarditis. It originates from skin infections, abscesses or vascular access sites (e.g. intravenous and central lines), or from intravenous drug misuse. Other causes of acute endocarditis include Strep. pneumoniae and Strep. pyogenes. Post-operative endocarditis after cardiac surgery may affect native or prosthetic heart valves or other prosthetic materials. The most common organism is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus (Staph. epidermidis), a normal skin commensal. There is frequently a history of post-operative wound infection with the same organism. Staph. epidermidis occasionally causes endocarditis in patients who have not had cardiac surgery, and its presence in blood cultures may be contamination. In Q fever endocarditis due to Coxiella burnetii, the patient often has a history of contact with farm animals. Gram-negative bacteria of the so-called HACEK group (Haemophilus spp., Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella spp. And Kingella kingae) are slow-growing fastidious organisms that are only revealed after prolonged culture and may be resistant to penicillin. Yeasts and fungi (Candida, Aspergillus) may attack previously normal or prosthetic valves, particularly in immunocompromised patients or those with indwelling intravenous lines. Abscesses and emboli are common, therapy is difficult (surgery is often required) Clinical presentation Patients can present with an acute illness and the classic features of a new or changing heart murmur and a fever. However, they may present with a subacute insidious illness. A high index of suspicion for the possibility of endocarditis is therefore required; Clinical signs tend to arise from the following pathological processes: systemic features of infection; cardiac lesions; embolization, and immune complex deposition Subacute endocarditis This should be suspected when a patient with congenital or valvular heart disease develops a persistent fever, complains of unusual tiredness, night sweats or weight loss, or develops new signs of valve dysfunction or heart failure. Less often, it presents as an embolic stroke or peripheral arterial embolism. Other features : include purpura and petechial haemorrhages in the skin and mucous membranes, and splinter haemorrhages under the fingernails or toe nails. Osler’s nodes are painful tender swellings at the fingertips that are probably the product of vasculitis. The spleen is frequently palpable; in Coxiella infections the spleen and the liver may be considerably enlarged. Microscopic haematuria is common. The finding of any of these features in a patient with persistent fever or malaise is an indication for re-examination to detect hitherto unrecognized heart disease. Acute endocarditis This presents as a severe febrile illness with prominent and changing heart murmurs and petechiae. Clinical stigmata of chronic endocarditis are usually absent. Abscesses may be detected on echocardiography. Partially treated acute endocarditis behaves like subacute endocarditis. Post-operative endocarditis This may present as an unexplained fever in a patient who has had heart valve surgery. The infectio may resemble subacute or acute endocarditis, depending on the virulence of the organism.Morbidity and mortality are high and redo surgery is required. Investigations Blood culture is the crucial investigation because it may identify the infection and guide antibiotic therapy. Three to six sets of blood cultures should be taken prior to commencing therapy and should not wait for episodes of pyrexia. The first two specimens will detect bacteraemia in 90% of culture-positive cases. Aseptic technique is essential and the risk of contaminants should be minimised by sampling from different venepuncture sites. An in-dwelling line should not be used to take cultures. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures are required. Echocardiography is key for detecting and following the progress of vegetations, for assessing valve damage and for detecting abscess formation. The sensitivity of transthoracic echo is approximately 65% but that of transoesophageal echo is more than 90%. Failure to detect vegetations does not exclude the diagnosis. Elevation of the ESR, a normocytic normochromic anaemia, and leucocytosis are common but not invariable. Measurement of serum CRP is more reliable than the ESR in monitoring progress. Proteinuria may occur and microscopic haematuria is usually present. The ECG may show the development of AV block (due to aortic root abscess formation) and occasionally infarction due to emboli. The chest X-ray may show evidence of cardiac failure and cardiomegaly. Principles of therapy Therapy of endocarditis is difficult because organisms reside within a protected site within the vegetation. High concentrations of intravenous antibiotic are required for prolonged periods to achieve successful treatment. Where possible, synergistic combinations of antibiotics are used, in order to maximize the microbiocidal effect. This is best achieved by a multidisciplinary approach consisting of clinicians, cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons and microbiologists. Drug therapy Empirical antibiotic treatment is started only after cultures are taken. The regimen is then adjusted according to culture results. The treatment should continue for 4-6 weeks, although studies of 2-week, short-course therapy have shown that it is highly effective in uncomplicated penicillin-sensitive Strep, viridans endocarditis. Typical therapeutic regimens are shown in Table below. Serum levels of gentamicin and vancomycin need to be monitored. In patients with penicillin allergy one of the glycopeptide antibiotics, vancomycin or teicoplanin, can be used. Penicillins, however, are fundamental to the therapy of bacterial endocarditis; allergies therefore seriously compromise the choice of antibiotics. Persistent fever Most patients with infective endocarditis should respond within 48 hours of initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy. This is evidenced by a resolution of fever, reduction in serum markers of infection (CRP tends to be the most sensitive) and relief of systemic symptoms of infection. Failure of this to occur needs to be taken very seriously. The following should be considered: ■perivalvular extension of infection and possible abscess formation ■drug reaction (the fever should promptly resolve after drug withdrawal) ■nosocomial infection (i.e. venous access site, UTI) ■pulmonary embolism(as a consequence of right-sided endocarditis or prolonged hospitalization). In such cases, samples for culture should be taken from all possible sites and evidence sought for the above causes. Changing antibiotic dosage or regimen should be avoided unless there are positive cultures or a drug reaction is suspected. Surgery Surgical intervention should be considered in the following cases: • Heart failure due to valve damage • Failure of antibiotic therapy (persistent or uncontrolled infection) • Large vegetations on left-sided heart valves with evidence or ‘high risk’ of systemic emboli • Abscess formation Prevention Until recently, antibiotic prophylaxis was routinely given to people at risk of infective endocarditis undergoing interventional procedures. However, as this has not been proven to be effective and the link between episodes of infective endocarditis and interventional procedures has not been demonstrated, antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer offered routinely for defined interventional procedures.