* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Paediatric Respiratory Medicine Dr Joseph Reisman_compressed

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

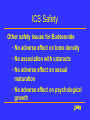

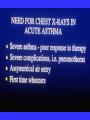

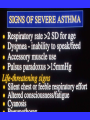

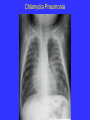

LMCC Review Lecture Pediatric Respiratory Medicine Joe Reisman MD, FRCP(C), MBA Pediatric Respirologist Chief of Pediatrics, CHEO Professor and Chairman, Department of Pediatrics Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa Normal Respiratory Rates Age Neonates Infant 1 yr 2 yr 3 yr Adolescent Respiratory Rate (breaths/min) 30-60 20-50 20-40 20-35 15-30 12-18 Asthma Definition • Asthma is characterized by paroxysmal or persistent symptoms such as dyspnea, chest tightness, wheezing, sputum production and cough associated with variable airflow limitation and hyperresponsiveness to endogenous or exogenous stimuli • Inflammation key to underlying mechanism for development and persistence of Asthma “Not All that Wheezes is Asthma” Differential Diagnosis • Infections – Bronchiolitis – Respiratory viruses – Pertussis – Sinusitis • Inflammatory – Asthma – Tuberculosis – Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia – Cystic Fibrosis “Not All that Wheezes is Asthma” Differential Diagnosis • Aspiration – Gastroesophageal reflux – Palatopharyngeal dyscoordination – Foreign body • Congenital Malformations – Vascular rings – Congenital cysts etc. • Miscellaneous – Congestive heart failure – Vocal chord adduction – Psychogenic causes Clinical Features suggestive of an alternative diagnosis to asthma History Symptoms presenting in neonatal period Requirement of ventilation in newborn period Wheeze associated with feeding or vomiting Sudden onset of cough/choking Steatorrhea Stridor Clinical features suggestive of an alternative diagnosis to asthma Physical Examination Failure to thrive Significant heart murmur Clubbing Unilateral signs Clinical features suggestive of an alternative diagnosis to asthma Investigations No reversibility of airflow obstruction with bronchodilator Focal, persistent or atypical radiographic findings Making the Diagnosis • History, Physical, Supporting Investigations • History of recurrent episodes of cough, wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness • Evidence of Atopy (history, physical, eosinophilia, family history) • Evaluate and exclude alternate diagnoses • Pulmonary function testing (6 years and older) – FEV1 and response to bronchodilator Response to Therapeutic Trial – Short-acting bronchodilators – Anti-inflammatory agents Types of Asthma in Young Children • Early Onset, Transient – Non-Atopic – Outgrown in approximately 60% children • Early Onset, Persistent – Associated with Atopy – Personal Atopy – Family History of Atopy Guideline Recommendations regarding Diagnosis • 1. Physicians must obtain appropriate patient and family history to assist them in recognizing the heterogeneity of wheezing phenotypes in pre-school aged children (Level III) • 2. In children unresponsive to asthma therapy, physicians must exclude other pathology that might suggest an alternative diagnosis (Level IV) • 3. The presence of atopy should be determined because it is a predictor of persistent asthma (Level III) Determination of Asthma Severity and Control • Severity may only be able to be determined once adequate asthma control is achieved • Asthma control should be assessed on a regular basis (continuity of care) • Base assessment of control on following criteria Criteria for Determining whether Asthma is Controlled Parameter Frequency or Value Daytime Symptoms < 4 days/week Night-time Symptoms <1 night/week Physical Activity Normal Exacerbations Mild, infrequent School Absence None Beta-2 Agonist need <4 doses/week FEV1 or PEF >90% personal best PEF diurnal variation < 10-15% Therapeutic Goals • Achieve and maintain acceptable asthma control • If poor control, identify reasons – Environment – Education – Drug and Dose – Inhaler technique – Compliance issues • Once good control is achieved, gradually reduce medication to minimum that maintains control, and reassess over time General Management of Asthma • If control is inadequate, reason or reasons should be identified, maintenance therapy should be modified • Any new treatment should be considered a therapeutic trial and its effectiveness should be assessed after 4-6 weeks • Inhaled corticosteroids should be introduced as initial maintenance therapy (Level I) even when patient reports symptoms fewer than 3 times per week • Although less effective than low dose ICSs, (Level I) LTRAs are alternative if patient can not or will not use ICSs (Level II) • If control is inadequate on low-dose ICSs, assess reasons for poor control and consider additional therapy with long-acting B2-agonists or LTRAs (Level I). • Severe asthma may require systemic corticosteroids • Asthma control and maintenance must be assessed regularly Frequent Reasons for Poor Asthma Control • Insufficient patient education in terms of what asthma is, and how it is controlled • Insufficient use of objective measures of airflow obstruction (PEF, FEV1), leading to over- or underestimation of asthma control • Misunderstanding regarding role and side effects of medications • Overuse of B2-agonists • Insufficient use of anti-inflammatory agents, including intermittent use, inadequate use, or lack of use • Inadequate assessment of patient adherence • Lack of continuity of care Regularly assess: Control Triggers Compliance InhalerTechnique Co-morbidity Asthma Therapy Pred Add-on therapy Inhaled Corticosteroids Fast-acting bronchodilator on demand Environmental control Education, Written action plan, and Follow-up Very mild Mild Moderate Moderately Severe Severe First Line Maintenance Therapy • Physicians should recommend inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) as the best option for anti-inflammatory therapy monotherapy for childhood asthma (Level I) • There is insufficient evidence to recommend leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) as first-line monotherapy for childhood asthma (Level I). For children who can not or will not use ICSs, LTRAs represent an alternative (Level II) ICS Benefits (Budesonide) • Clinical measures of control strongly favored Budesonide over Placebo – Symptoms – Rescue medication use and prednisone courses – Episode-free days – Hospitalizations and urgent care – Initiation of beclomethasone or additional asthma medication CAMP Study, NEJM Oct 13, 2000 Growth Effects of Budesonide Budesonide growth effect • Led to limited, small, and apparently transient reduction in growth velocity • Projected final height by bone age similar to Placebo ICS Safety Other safety issues for Budesonide • No adverse effect on bone density • No association with cataracts • No adverse effect on sexual maturation • No adverse effect on psychological growth Add-on Therapies • Long-acting B2-agonists are not recommended as maintenance monotherapy for asthma (Level I) • After reassessment of compliance, control of environment and diagnosis, if asthma is not optimally controlled with low doses of ICSs, therapy should be modified by the addition of a long-acting B2-agonist (Level I) • Alternatively, addition of an LTRA or increasing to a moderate dose of ICS may be considered (Level1) Inhalation Devices • At each contact, health care professionals should work with patients and their families on inhaler technique (Level I) • When prescribing MDIs, physicians should recommend use of a valved spacer, with mouthpiece when possible, for all children (Level II) • Dry powder breath-actuated devices offer a simpler form of maintenance therapy in children over 5 years of age (Level IV) • Children tend to “auto-scale” their inhaled medication dose and the same dose of maintenance medication can be used at all ages for all medications (Level IV) • Physicians, educators and families should be aware that jet nebulizers are rarely indicated for the treatment of chronic or acute asthma (Level I) Prevention Strategies for Asthma Primary Prevention • With conflicting data on early life exposure to pets, no general recommendations can be made with regard to pets for primary prevention of allergy and asthma (Level III). Families with biparental atopy should avoid having cats or dogs in the home (Level II) • There are conflicting and insufficient data for physicians to recommend for or against breastfeeding specifically for the prevention of asthma (Level III). Due to its many other benefits, breastfeeding should be recommended Prevention Strategies for Asthma Secondary Prevention • Health care professionals should continue to recommend the avoidance of tobacco smoke in the environment (Level IV) • For patients sensitized to house dust mites, physicians should encourage appropriate environmental control (Level V) • In infants and children who are atopic, but do not have asthma, data are insufficient for physicians to recommend other specific preventive strategies (Level II) Our Patients and their Parents Still Smoke….. 50% of Children with Asthma are Sensitive to House Dust Mite Prevention Strategies for Asthma Tertiary Prevention • Allergens to which a person is sensitized should be identified (Level I), and a systematic program to eliminate, or at least to substantially reduce, allergen exposure in sensitized people should be undertaken (Level II) EDUCATION Education and Follow-up • Asthma control criteria should be assessed at each visit (Level IV). Measurement of pulmonary function, preferably by spirometry, should be done regularly (Level III) in adults and children over 6 years of age • Socioeconomic and cultural factors should be taken into account in designing asthma education programs (Level II). • School age children may benefit from education programs separate from their parents OXYGEN Asthma Rx Differential Diagnosis of Croup • Epiglottitis • Bacterial Tracheitis • Foreign Body in Airway or Esophagus Management of Croup • Avoid agitation as much as possible • Mild croup may be managed at home with p.o. fluids and humidity • Warn parents croup may be: • Worse at night • May clear in cold air outside Management of Croup cont’d • Stridor at rest, moderate chest wall retractions, and an anxious, restless child are all indicators of moderate to severe disease and signal need for hospitalization • Nurse in Oxygen (usually 30-40%) • If concerned about degree of respiratory failure, arterial blood gas indicated Management of Croup cont’d • Racemic epinephrine 0.5 mL of 2.25% solution in 3 mL normal saline by inhalation X 1 dose may provide relief • Effect may last 30-60 minutes; may repeat q1-2h • Dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg (MAX: 12 mg) (PO, IM, IV) X 1 dose • A child who has received racemic epinephrine should be admitted for observation Management of Croup cont’d • If there is a question of impending respiratory failure, obtain arterial blood gases • A rising respiratory rate correlates well with a falling PaO2 • Hypercapnea (rising PaCO2) occurs late in upper respiratory tract obstruction and is a sign of increasing respiratory failure Bronchiolitis • • • • Affects approximately 50% children < 2 years of age Peak incidence 6-8 months, winter, spring RSV accounts for >50% of cases Parainfluenza type 3, influenza, adenovirus, ?rhinovirus can also be causes • Usually viral prodrome with cough, URTI symptoms • Most often mild disease • Can affect those with underlying cardiac, lung disease more severely Bronchiolitis cont’d • Wheezing, tachypnea, tachycardia, respiratory distress lasting 5-7 days • CXray may show hyperinflation, increased peribronchial markings, areas of atelectasis, linear densities • NP swab to detect viral etiology (immunofluorescence) • Oximetry - keep O2 sat > 92% with humidified O2 • Trial of salbutamol or racemic epinephrine • Admit if persistent tachypnea, respiratory distress, very young infants, persistent hypoxia • Antibiotics have no role unless also suspect complicating bacterial disease • Consider prophylaxis of those high risk patients (BPD, cardiac disease etc.) with Palivizumab (monoclonal antibody against RSV) monthly during RSV season Management of Pneumonia- Investigations • • • • • • • • CBC, differential count Blood culture Sputum for culture (if child is old enough) Arterial blood gas if respiratory distress Tuberculin skin test with Candida control Cold agglutinin titer Chest X-ray PA and Lat Diagnostic thoracentesis if significant amount of pleural fluid Management of Pneumonia- Treatment • General supportive care including PO or IV fluids • O2 as needed • IV or PO antibiotics appropriate for most likely etiologic organism or organism cultured • Admission based on clinical status • Empyema requires chest tube drainage • Consider anaerobic coverage if aspiration a possibility Pneumonia- Treatment Pertussis • Pertussis is an important cause of chronic cough • The Chinese named Pertussis “the 100 Day Cough” • Immunization does not guarantee protection from Pertussis • Cough may have classic “inspiratory whoop” in chronic phase Chlamydia Pneumonia Chlamydia Pneumonia TB remains an important infection! Measure the induration when performing a 5-TU tuberculin skin test RDS- Early Changes BPD- late changes Case Presentation- Patient L.M. • 40 day old infant admitted to CHEO January 15 2003, with 4 day Hx of wheezy illness; RSV +ve • Hx intermittent cough since 2 weeks of age • Slow weight gain since birth; B.W. 3640g; weight on admission 4080g • Hx of “greasy” stools • Meconium took about 2 weeks to pass • Hx of hypo echoic bowel on prenatal ultrasound • O/E scrawny infant with crackles over left anterior and lateral chest; wheezes bilaterally • Sweat Chloride Tests x 2: 82 and 91 mEq/L Psychosocial Issues • Both Parents and Patients can present with a wide array of psychosocial issues • Coping with a chronic condition • Compliance Issues • Adolescence Issues • Death and Dying Issues • Issues regarding drug plans and financial support Agents Aimed at Altering Properties of CF Mucus • N-acetylcysteine- no longer used due to bronchial irritability • Recombinant Human DNase (dornase alpha)- breaks down DNA from dead neutrophils; administered as 2.5 mg once daily by aerosol. Studies of sustained improvement or decreased decline in PFT’s have yielded mixed results (Ramsey et al, Am Rev Respir Dis, 1993); (Fuchs et al, NEJM 1994) • Not an inexpensive therapy