* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download WHTL-5982 - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

Survey

Document related concepts

Yemenite Jewish poetry wikipedia , lookup

Self-hating Jew wikipedia , lookup

The Invention of the Jewish People wikipedia , lookup

Hamburg Temple disputes wikipedia , lookup

Independent minyan wikipedia , lookup

Interfaith marriage in Judaism wikipedia , lookup

History of the Jews in Vancouver wikipedia , lookup

Romaniote Jews wikipedia , lookup

Jewish religious movements wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on religious pluralism wikipedia , lookup

Index of Jewish history-related articles wikipedia , lookup

History of the Jews in Gdańsk wikipedia , lookup

Jewish military history wikipedia , lookup

The Reform Jewish cantorate during the 19th century wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Old Synagogue and Mikveh in Erfurt –

Testimonies of everyday life, religion

and town history between change and

continuity

Germany

Date of Submission: 15/02/2015

Criteria: (iii)(iv)(vi)

Category: Cultural

Submitted by:

Permanent Delegation of Germany to UNESCO

State, Province or Region:

Thuringia

Coordinates: N44 31 94 E56 49 70

Ref.: 5982

Description

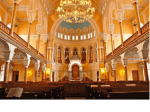

The Old Synagogue

The Old Synagogue is situated in the immediate city centre, at the core of the Erfurt historic

centre. Today, it is located on the site of Waagegasse No. 8, between Benediktsplatz,

Michaelisstraße, Fischmarkt and City Hall. The synagogue's location without direct visibility from

the street is typical of medieval synagogues in quarters inhabited by Jews and Christians alike.

The synagogue was the centre of community life and hence of the Jewish settlement.

The Old Synagogue's architectural history reflects the history of the Jewish community in Erfurt

in the Middle Ages. Yet it also bears testimony to subsequent conversions and changes to the

building. The oldest parts of the western wall date back to as far as the end of the 11th century

and are thus generally the earliest evidence of a Jewish community in Erfurt: a timber from this

first construction phase has been dendro-dated to 1094. Nowadays, it cannot be reconstructed

exactly what the building looked like in this early period. The same applies to the second

construction phase of the 12th century. Here again, only a short stretch of the western wall with

a sandstone double-arched window (biforium) has been preserved.

Around 1270, the Jewish community erected a large and prestigious synagogue, incorporating

parts of the previous building. Even today, the representative western façade with five lancet

windows and a large tracery rosette effectively shapes the synagogue's outer appearance. The

high interior was spanned by a timber barrel vault. Shortly after 1300, the synagogue was

expanded by a few metres to the north and another storey was added. The extension, largely

preserved to date, had a magnificent symmetrical façade with the synagogue entrance in the

middle and five formerly tall lancet windows laid out in a row above the doorway. It possibly

housed the women's synagogue, traditionally separated from the main prayer room, or else

served as a school for the boys' Hebrew lessons.

After the devastating pogrom of 1349, which also caused severe damage to the synagogue, the

city of Erfurt acquired the building and subsequently sold it to a local merchant. He converted

the synagogue into a warehouse by fitting in a vaulted cellar, splitting up the main prayer room

into several storeys with two solid timber ceilings and erecting a new roof truss. Nearly the

entire synagogal interior fell victim to this conversion: the bimah (lectern) was destroyed, as was

the torah shrine on the eastern wall, where a major gateway is located since the mid-14th

century. Only the cornice once running around the main prayer room has been partly preserved.

It was used to place lamps or candles for lighting the synagogue during services.

Since the late 19th century, the former synagogue was used for gastronomical purposes and

had been transformed to that effect: a ballroom, kitchen and dining areas and even two bowling

alleys were created. It was due to these changes as well as to adjacent buildings on all sides

that the original synagogal edifice was hardly recognizable for a long time. For that reason, the

building remained virtually unknown to general perception, fortunately also during the Third

Reich.

Only since the late 1980s has the synagogue returned to public awareness and in 1992, the

building historian Elmar Altwasser began to examine it. The researches were completed in 2007

and published in 2009 (see literature). In 1998, the city of Erfurt purchased the building and had

it extensively researched and renovated over the course of the following years. During

renovation, great emphasis was put on the preservation of all traces of use: those dating from

synagogal use as well as those from later alterations. Owing to this careful conservation and

restoration, medieval as well as younger building phases are still easy to perceive from the

building. At the same time, modern conversions and alterations are clearly distinguishable from

historic ones.

Now housing a museum on the history of Erfurt's Jewish community in the Middle Ages, the

synagogue has found an appropriate use anew.

The Mikveh

In spring 2007, the remains of the medieval mikveh were discovered during renovation works on

the open space northwest of Merchants' Bridge. The Mainz "Heberolle" of 1248/49 is the first to

mention the mikveh in Erfurt; in the interest rate registers of St. Severus Church it can be traced

back as far as around 1250. The Jewish community is named there as the owner of the plot of

land on Krautgasse (immediately north of Merchants' Bridge), on which the Cold Bath ("Frigido

balneo") was located. The community had to pay annual dues of 2 gulden for it, initially to the

bishop, later to the city. Until 1618, the term "cold bath" remained the plot's specification, even

though it had long lost its original function. The cold bath is clearly recognizable as a ritual bath

– written sources generally refer to regular baths as a "stupa".

The mikveh's walls are of extraordinary quality. Vault and upper mural parts are walled up in

even layers of limestone. The building, about 9 metres long and just under 3 metres wide on the

inside, features an alcove in its northern wall, presumably used for depositing clothes. The

basin, located on the eastern wall, takes up its complete width. In the basin area, a change in

the masonry catches the eye: here, approximately on medieval groundwater level, several

layers of large sandstone ashlars are fitted into the wall in a way which is found in no other

Erfurt cellar. The basin itself was reached by a staircase whose course can still be retraced by

the former stairs' imprints on the northern wall. According to instructions, the bath was supplied

with groundwater, which was constantly available due to the river Gera close by. The stairs

permitted complete immersion at all times, seasonal fluctuations were thus easily

counterbalanced.

The mikveh structure, according to first assessment erected in the 13th century, reclined on the

southern wall of at least one preceding building in the same spot. While this wall could merely

be dated very roughly into Romanesque times at first, its age determination received a new hint

when, only in 2010, a small stone sculpture was discovered on one of the huge sandstone

ashlars: The head, approximately 30 cm tall and of remarkable handicraft, wears a crown with a

lily and can thus possibly be identified as a portrait of King David. It originates from the first half

of the 12th century, thus adding the first mikveh building, the supposed source of the boulders,

to the small group of early mikvaot in Germany. Moreover, it is the only known mikveh so far

with figurative sculpture (Karin Sczech, TLDA).

The archaeological excavation was concluded in 2010, its results are due for publishing in 2013

(see Literature). After having concluded the excavation works, the erection of a protective

building began, defending the remains of the medieval mikveh from external influences on the

one hand and enabling its exhibition on the other. Since September 2011, the mikveh is

accessible to visitors within guided tours.

The "Stone House"

In a complex of buildings on Benediktsplatz 1 in the historic city centre, surrounded by younger

structural elements, a medieval stone structure is located. The building rises above a medieval

cellar whose earliest construction phases can be dated into the 12th century by a Romanesque

portal. Yet the edifice predominantly dates from the 13th and was merely changed in few parts

during the 14th century. Exceptionally numerous essential structures from its time of

construction around 1250 have been preserved, among those the portals to both main storeys,

the beamed storey ceiling, the original stepped gable as well as the wooden roof structure.

Unique throughout Germany is the upper storey's room interior with a lancet arched vented

lighting niche, hardly changed outer walls with scored joints as well as a painted beam

ceiling. The boards of the ceiling are consistently decorated with a wheel motif, while each of

the beams features different ornamentation. The beams have been dendro-dated to

1241/42. The so-called "Stone House" is an exceptional testimony of late medieval secular building culture. What is

more, thanks to the analysis of medieval tax lists, the edifice can be related to Jewish owners from the end of the

13th century at the latest.

Justification of Outstanding Universal Value

In the largely intact Old Town of Erfurt, unique evidence of the important Jewish community from the late 11th to the

mid-14th century has been preserved: the Old Synagogue, one of the oldest, largest and best preserved medieval

synagogues, its appendant mikveh and a secular building. The conserved buildings are complemented and enhanced

by an unequalled abundance of original objects such as gravestones, manuscripts and the globally unique Erfurt

Treasure. Together, they offer priceless clues to Jewish community and everyday life as well as to the coexistence of

Jews and Christians in medieval cities. Nowhere else can so many exceptional and authentic testimonies be found

gathered in one place to which they are also historically related. Erfurt is an outstanding example of the early heyday

of Central European Jewish culture before it was brutally disrupted by the "Black Death" pogroms in the mid-14th

century.

Criterion (iii): Unique testimony to the culture of Central European Jewry in the Middle Ages

The Old Synagogue is the best preserved synagogue in Central Europe, its oldest parts dating back to the late 11th

century. It is complemented by the medieval mikveh, the "Stone House" and singular authentic objects: The Hebrew

Manuscripts from the Erfurt Jewish Community, the Erfurt Jewish Oath (dating back to late 12th century, it is the

oldest preserved Jewish Oath in the German tongue), a Bronze Lamp, originating around the year 1200 (the oldest

known example of its kind) as well as around 60 preserved tombstones from the 13th to 15th century from the former

Jewish cemetery. What is more, the "Erfurt Treasure", with a weight of nearly 30 kg the largest and one of the most

important hoards of medieval Jewish property from the 14th century, offers inestimable insight on status, everyday life

and trading relations of wealthy Jews as citizens of central European towns and cities.

Together, they bear witness to an era when Jewish presence moulded European culture, economy and society. The

knowledge it provides about the Jewish community between approx. 1200 and 1349 illuminates, in unrivalled detail,

the status of medieval Jewish communities as part of urban society as well as the tense relations between Jews and

Christians in everyday and religious life. Erfurt's Jewish heritage thus is a showcase of Jewish communities in

Ashkenaz, the settlement area of Central European Jewry.

Criterion (iv): Outstanding examples of medieval Jewish religious and secular architecture

The Old Synagogue's quality and state of conservation are exceptional, especially in comparison to other preserved

synagogues of a similar age. Its architectural history mirrors in a distinct manner the story of a Jewish community and

its highly charged relations to its Christian surroundings. Beginning in the 11th century the Jewish community

increased and flourished until the riots and persecution, which culminated in its complete extinction during the

pogrom of 21 March 1349. At the same time, general developments in Jewish sacred architecture between the 11th

and 14th century can be understood. Put into context with various Erfurt churches, different concepts of sacred

spaces become apparent. Due to conversions and alterations of the 19th century when the synagogue housed a

restaurant and a ballroom, its original design was hardly recognizable for a long time. Hence, it was virtually unknown

to general perception and thus remained intact during the Third Reich.

The mikveh belongs to the range of early medieval Jewish ritual baths in Europe. Its main construction phase is to be

dated to the mid-13th century; one older building phase is traceable. The building's shape is unusual and so far

unequalled.

Europe-wide, the so-called "Stone House" is one of the few remaining buildings from this era. Without doubt owned

by Jews since 1293 at the latest, it features an original painted beam ceiling from the mid-13th century. It is thus an

outstanding example of a medieval secular building from a Jewish context.

Criterion (vi): Direct association with Judaism and its reception by its Christian surroundings

The coexistence, incessant discourse and dispute between Jews and Christians have shaped and defined Europe

over centuries. Erfurt's rise to scholarly and economic prosperity is a showcase of urban development in the Middle

Ages. The contribution of Jewish communities to this age-long process is so far underestimated. Today, medieval

Jewish rite, Jewish everyday life as well as Jewish-Christian coexistence are documented in Erfurt with a number of

authentic testimonies unrivalled by any other known site worldwide. Yet the same testimonies also bear witness to

conflict, persecution and expulsion of Jews in the Middle Ages which is inseparably linked to common memory. In this

context, treatment of the Old Synagogue is also exemplary: Beginning with its conversion into a storehouse in the

aftermath of the 1349 pogrom, its age-long oblivion until its recent rediscovery and its renewed life as a museum for

the history of the Jewish community of medieval Erfurt. In this way Erfurt fulfils Germany's particular historical

responsibility to commemorate the common cultural heritage of Judaism and Christianity in Europe and to honour the

age-long defining contribution of Jewish citizens to scholarliness and prosperity and therefore to German and

European culture and society.

Statements of authenticity and/or integrity

The Old Synagogue's architectural history reflects all building phases and its various uses from its time of

construction up to subsequent conversions and latest changes to the building in the 19th century on the basis of its

original parts. Most parts of the building, however, date from the construction phases around 1250-1320 when it was

used as a synagogue. After 1350, the synagogue was converted into a storehouse, since the 19th century it was

used gastronomically. The traces of these later uses, too, were preserved during restoration, as they were deemed to

be the reason the medieval structures survived.

The Old Synagogue is enhanced in its impact and significance by a mikveh, excavated in 2007 in the immediate

historic city centre as well as a medieval secular building, the "Stone House", in Jewish possession since late 13th

century and mostly unaltered since that time. In addition, there are singular authentic objects with an exceptional

validity for Jewish culture in Central Europe, globally unique in their sheer plenty. The Jewish-medieval heritage of

Erfurt as a whole stands out as an exceptional example of metropolitan and community culture in medieval

Ashkenaz.

Comparison with other similar properties

From the range of few preserved Jewish ritual buildings from the Middle Ages, the Old Synagogue stands out as one

of the oldest, largest and best preserved prayer rooms in Central Europe. Comparable buildings have either been

destroyed and rebuilt or are preserved to a much lesser extent. Sites representing this early height of Jewish life in

Central Europe are currently not listed as World Heritage. In addition to sites of biblical Judaism (Masada, Biblical

Tels of Megiddo, Hazor, Beer Sheba) as well as sites serving as centres of the three world religions Judaism,

Christianity and Islam (Jerusalem, Toledo, Saint Catherine Area), only the World Heritage Site "Jewish Quarter and

St Procopius' Basilica in Třebíč" (Czech Republic) relates to ashkenazic Jewry. It commemorates the coexistence of

Jewish and Christian culture from the Middle Ages up to the 20th century. Medieval synagogues and mikvaot as

testimonies of Jewish religion and culture are so far not listed as self-contained World Heritage Sites. Even younger

synagogues, which have been preserved slightly more often, are either not represented on the World Heritage List or

merely so as part of a historic Old Town (Prague, Cracow, Bardejov).

Owing to its size and quality, the Erfurt Mikveh can be classified as a monumental mikveh similarly to the well-known

shaft mikvaot preserved for instance in Cologne, Speyer, Worms and Friedberg (Hesse). Unlike these, however, it

represents an entirely different and so far singular type of medieval Jewish ritual bath.

The "Stone House" with its original interior is unique throughout Europe.

The recent Erfurt rediscoveries and intense scientific research they have triggered significantly broadened the

existing knowledge of Jewish settlement and cultural history of the early and high Middle Ages. The abundance of

authentic architectural heritage should be seen in context with the previous state of research chiefly based on written

sources. On the other hand, material testimonies such as the Erfurt Hebrew Manuscripts have raised an entire set of

new questions. In addressing these, further far-reaching insights on Jewish-European history can be expected over

the forthcoming years.